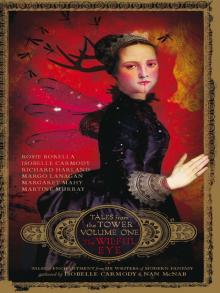

The Wilful Eye

Isobelle Carmody

First published in 2011

Copyright © in this collection Isobelle Carmody and Nan McNab, 2011

Copyright © ‘Eternity’, Rosie Borella, 2011

Copyright © ‘Moth’s Tale’, Isobelle Carmody, 2011

Copyright © ‘Heart of the Beast’, Richard Harland, 2011

Copyright ©‘Catastrophic Disruption of the Head’, Margo Lanagan, 2011

Copyright © ‘Wolf Night’, Margaret Mahy, 2011

Copyright © ‘One Window’, Martine Murray, 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australia www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 440 6

Cover and text design by Zoë Sadokierski

Typeset ans eBook production by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

INTRODUCTION

CATASTROPHIC

DISTRIBUTION of the HEAD

by Margo Lanagan

MOTH'S TALE

by Isobelle Carmody

ETERNITY

by Rosie Borella

HEART of the BEAST

by Richard Harland

WOLF NIGHT

by Margaret Mahy

ONE WINDOW

by Martine Murray

For Ann Jungman

who is one of the most honourable and

truly good-hearted human beings I have ever known.

If life were a fairytale, you would be a good witch.

INTRODUCTION

When I was a child, I did not love fairytales. They led you into the dark woods and left you there to fend for yourself with no understanding of where you were or why you had been brought there and no idea of how to find your way back.

They frightened me almost as much as they fascinated me with their vivid strangeness. There were rules in them and they were rigid, but they were not the rules that governed my world, and the results of disobedience were unpredictable. The adults behaved differently from how adults were meant to behave. Fathers and kings were weak and careless or blood-drenched tyrants. Queens and mothers were ruthless and vain and sometimes wicked. Guides were sly and deceptive. Children were often in mortal danger.

The world of fairytales was not how the real world was represented to me by adults, who spoke of reason and fairness. Nor did fairytales offer the comforting magic of such fantasies as Enid Blyton’s The Magic Faraway Tree. They felt powerful and important, thrilling as well as frightening. I often felt that I was being shown things I was not supposed to see, that there was something in fairytales beyond my ability to understand, something adult and difficult and possibly painful. I both wanted to understand and feared to understand in the same way that I wanted and feared to become an adult.

The many cruel indelible details in fairytales gave me nightmares: the red dancing shoes that grew onto the feet of the disobedient girl who had bought them and which, when severed by a woodcutter, danced bloodily into the sunset; the way Hansel poked a bone out of his cage so the blind witch would think he was not fat enough to eat; the slimy feel of the frog against the lips of the princess who had to kiss him because she had promised to do so; the incriminating bloodstain that appeared on the key Bluebeard gave his young wife, when she disobeyed him.

In fairytales, tasks are tripled, certain phrases are repeated: the wolf chants over and over that he will blow the house down, the troll asks repeatedly who is trit-trotting over his bridge, Otesanek lists all that he has consumed over and over. All of these things generate the anxious feeling of impending and inexorable disaster. Right from the beginning, there is a sense that something dreadful is going to happen.

When I grew up, I came to love fairytales for all the things that had frightened me when I was a child. I understood that a fairytale worked through obscure but vivid archetypes and strange opaque metamorphoses. A fairytale did not try to explain itself. It was not exploring or analysing anything. It did not offer rational or obvious answers or advice. It was like an eruption that you could not help but feel and react to in some visceral way.

A fairytale is short, but it is not a short story. A fairytale does not explore or analyse but a short story can do both. Short stories often do not need to explain or sum up everything or come to a conclusion as longer works often do, perhaps in part because they have the leisure of time and space. Fairytales nevertheless usually have a feeling of completeness, as if everything is finally where it should be. The short story form allows evocation, suggestion, implication. Its potency often lies in what it does not say.

I can vividly remember the breathless thrill I felt at the last profound image of the panther padding backwards and forwards in the cage that had been occupied by Kafka’s hunger artist. It is not explained or analysed. It is left to us to make of it what we can and there is no page at the back to tell us if we are right or wrong. This, incidentally, is how fairytales work, though one is always inclined to want to draw a moral from them. The form seems to be shaped for that, which may be why they were handed down to children. It is interesting that the worst retellings of traditional fairytales are those that heavy-handedly take the step of making a moral point.

Long fiction is wonderful and you can lose yourself in it as a reader and as a writer, but short stories don’t allow the same kind of immersion. Often the best stories hold you back and make you witness them. This may be one of the reasons some people reject the form. That and the fact that they are harder work to read. A story will not let you get comfortable and settle in. It is like a stool that is so small that you must always be aware of sitting. I love writing short stories because the form will not permit me to forget about it, and because it allows me a freedom to do things that I cannot do in a novel, such as focusing in very closely on a single event or thought. Of course there are novels that do it, such as Peter Handke’s chilly, brilliant Afternoon of a Writer, but I would say that was a novel written like a short story. A short story does not need to be completed in the same way a novel must be finished. Even if it is a slice of life story, there is always something open about it.

Perhaps one of the things I love most about the form is that a short story can be intoxicatingly, provokingly open-ended. So can a novel, you might say, but again I would say that is a different sort of openness. Tim Winton’s The Riders is open-ended, meaning that we don’t ever come to understand certain things, but in a way the story is not open-ended because we sense that all has been said that can be said of this man’s love, obsession, pursuit of woman. We understand that the seeking and the hunger to find her are actually a hunger to find himself or some aspect of himself, or that it is an exploration of the space in him which cries out for the missing woman.

Another thing I love about short stories is that images can dominate like a mysterious t

ower on a hill. Short stories do not say this happened and this happened and this happened. They are a microcosm and a magnification rather than a linear progression.

The idea of using the short story form to explore fairytales came to me one day after I had been thinking about how fairytales are considered to be children’s stories, when in fact they are ancient stories passed on to children because the adult world no longer sees them as relevant or interesting. The moment they were handed over to children, they lost their gloss and could never be admitted to the adult world again. They had lost their value. Yet paradoxically, I did not love them as a child, and I adore them as an adult. My thoughts turned to Angela Carter’s collection, The Bloody Chamber, which removes several fairytales from the sticky grasp of children and allows them their full, rich, gothic, gritty, dangerous potency before serving them up for adult consumption. No one would dare to say they were irrelevant or childish. I thought how exciting it would be not only to try to do this myself but to see what other writers of short stories would make of fairytales they had loved or hated as children, now that they were adults and there was no need to censor themselves, if they were invited to take them seriously and interpret them in any way they wanted.

The idea was exciting to me as a reader and as a writer.

I had completed my own collection of short stories in Green Monkey Dreams, and with a few notable exceptions, I was not much drawn to collections of short stories by many different authors. I think there are too many of them, despite the fact that short stories are considered hard to sell. The number of such collections seems to me to be the result of marketing departments, which weigh the perceived and perhaps genuine difficulty of selling short stories against the advantages of a list of saleable names on the cover. That many of those names belong to writers better known for their novels and long fiction rather than for their ability to write short stories is irrelevant. That the collection will sell is its entire reason for existence, and if there is a theme, it is usually something thought up by a team as a marketable idea. It is the literary equivalent of one of those prefabricated boy or girl groups where a stylist manufactures each band member’s look and persona with an eye on the market demographic. My own preference as a reader has always been for collections of stories by one writer, because they will be informed by some sort of creative idea, and it is likely the stories will resonate with one another and tell a larger story, even if the writer did not intend it.

It is ironic, then, that I should come up with an idea that would result in a collection of stories by different authors. My original idea was to have a collection of novellas, each by a different author, but this was deemed unsaleable once I brought the idea to a publisher. The form changed shape several times before we settled on the right publisher and a final form: two big, beautiful, lush books with covers that would make it clear the content was strong, sensual, diverse and serious, six long stories to each book, arranged to resonate most powerfully with one another.

Long before we went to a publisher, Nan and I had made a list of desirable authors, people whom we knew could write stories of the type we wanted. We wrote to each of them individually, outlining the project. We had high hopes when all of them responded with enthusiasm and chose the fairytale they wanted to explore. Once the choice was made, that fairytale was off limits to everyone else. Nan and I, who were to be participating editors, chose our tales, and in due course the stories began to come in. Reading though them we quickly realised the collection was going to spill out of the original concept, in form and also in content, some of the stories roaming far from the original or being lesser-known folktales, but the result of the overflow was so exciting, the depth and potency of the stories offered so breathtaking, that we decided to encompass them.

The twelve stories that make up the collection are very diverse, not only because each arises from a different fairytale, but because each is a profound exploration, through fairytale, of themes important to the individual writers. They chose their stories consciously and subconsciously, and the depth of their choice is reflected in the depth of their stories.

That the stories are as powerful as they are is the result of the writers’ abilities to be inspired by the stories that shaped all of us. You will find in them the universal themes of envy and desire, control and power, abandonment and discovery, courage and sacrifice, violence and love. They are about relationships – between children and parents, between lovers, between humans and the natural world, between our higher and lower selves. Characters are enchanted, they transgress, they yearn, they hunger, they hate and sometimes, they kill. Some of the stories are set against very traditional fairytale backgrounds while others are set in the distant future. Some are set in the present and some in an alternative present. The stories offer no prescription for living or moral advice and none of them belongs in a nursery.

The final result is this book and the one to follow. These two towers have taken time to erect. They are full of mystery and dangerous sensuality.

All that remains is for you to enter and submit to their enchantment . . .

Who believes in his own death? I’ve seen how men stop being, how people that you spoke to and traded with slump to bleeding and lie still, and never rise again. I have my own shiny scars, now; I’ve a head full of stories that goat-men will never believe. And I can tell you: with everyone dying around you, still you can remain unharmed. Some boss-soldier will pull you out roughly at the end, while the machines in the air fling fire down on the enemy, halting the chatter of their guns – at last, at last! – when nothing on the ground would quiet it. I always thought I would be one of those lucky ones, and it turns out that I am. The men who go home as stories on others’ lips? They fell in front of me, next to me; I could have been dead just as instantly, or maimed worse than dead. I steeled myself before every fight, and shat myself. But still another part of me stayed serene, didn’t it. And was justified in that, wasn’t it, for here I am: all in one piece, wealthy, powerful, safe, and on the point of becoming king.

I have the king by the neck. I push my pistol into his mouth, and he gags. He does not know how to fight, hasn’t the first clue. He smells nice, expensive. I swing him out from me. I blow out the back of his head. All sound goes out of the world.

I went to the war because elsewhere was glamorous to me. Men had passed through the mountains, one or two of them every year of my life, speaking of what they had come from, and where they were going. All those events and places showed me, with their colour and their mystery and their crowdedness, how simple an existence I had here with my people – and how confined, though the sky was broad above us, though we walked the hills and mountains freely with our flocks. The fathers drank up their words, the mothers hurried to feed them, and silently watched and listened. I wanted to bring news home and be the feted man and the respected, the one explaining, not the one all eyes and questions among the goats and children.

I went for the adventure and the cleverness of these men’s lives and the scheming. I wanted to live in those stories they told. The boss-soldiers and all their equipment and belongings and weapons and information, and all the other people grasping after those things – I wanted to play them off against each other as these men said they did, and gather the money and food and toys that fell between. One of those silvery capsules, that opened like a seed-case and twinkled and tinkled, that you used for talking to your contact in the hills or among the bosses – I wanted one of those.

There was also the game of the fighting itself. A man might lose that game, they told us, at any moment, and in the least dignified manner, toileting in a ditch, or putting food on his plate at the barracks, or having at a whore in the tents nearby. (There were lots of whores, they told the fathers; every woman was a whore there; some of them did not even take your money, but went with you for the sheer love of whoring.) But look, here was this stranger whole and healthy among us, and all he had was that scar on his arm, smooth and harmless, for all his

stories of a head rolling into his lap, and of men up dancing one moment, and stilled forever the next. He was here, eating our food and laughing. The others were only words; they might be stories and no more, boasting and no more. I watched my father and uncles, and some could believe our visitor and some could not, that he had seen so many deaths, and so vividly.

‘You are different,’ whispers the princess, almost crouched there, looking up at me. ‘You were gentle and kind before. What has happened? What has changed?’

I was standing in a wasteland, very cold. An old woman lay dead, blown backwards off the stump she’d been sitting on; the pistol that had taken her face off was in my hand – mine, that the bosses had given me to fight with, that I was smuggling home. My wrist hummed from the shot, my fingertips tingled.

I still had some swagger in me, from the stuff my drugs-man had given me, my going-home gift, his farewell spliff to me, with good powder in it, that I had half-smoked as I walked here. I lifted the pistol and sniffed the tip, and the smoke stung in my nostrils. Then the hand with the pistol fell to my side, and I was only cold and mystified. An explosion will do that, wake you up from whatever drug is running your mind, dismiss whatever dream, and sharply.

I put the pistol back in my belt. What had she done, the old biddy, to annoy me so? I went around the stump and looked at her. She was only disgusting the way old women are always disgusting, with a layer of filth on her such as war always leaves. She had no weapon; she could not have been dangerous to me in any way. Her face was clean and bright between her dirt-black hands – not like a face, of course, but clean red tissue, clean white bone-shards. I was annoyed with myself, mildly, for not leaving her alive so that she could tell me what all this was about. I glared at her facelessness, watching in case the drug should make her dead face speak, mouthless as she was. But she only lay, looking blankly, redly at the sky.