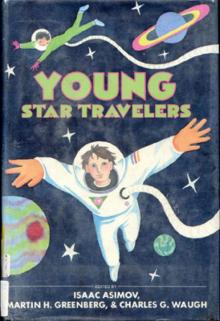

Young Star Travelers

Isaac Asimov

YOUNG STAR TRAVELERS

EDITED BY Isaac Asimov, Martin H. Greenberg, and Charles C. Waugh

* * *

HARPER & ROW, PUBLISHERS

Young Star Travelers

Copyright © 1986 by Nightfall, Inc., Martin H. Greenberg, and Charles G. Waugh

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America. For information address Harper & Row Junior Books, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, N. Y. 10022. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto.

Designed by Joyce Hopkins 123456789 10

First Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Main entry under title:

Young star travelers.

Summary: A collection of nine science fiction stories about children who have traveled in space.

1. Science fiction, American. 2. Science fiction, English. [1. Space flight—Fiction. 2. Science fiction.

3. Short stories] I. Asimov, Isaac, 1920

II. Greenberg, Martin Harry. III. Waugh, Charles.

PZ5.Y8517 1986 [Fic] 85-45276

ISBN 0-06-020178-9

ISBN 0-06-020179-7 (lib. bdg.)

Acknowledgments

“If I Forget Thee, Oh Earth ...” by Arthur C. Clarke. Copyright © 1951; renewed © 1979 by Arthur C. Clarke. Reprinted by permission of the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc., 845 Third Ave., New York, NY 10022.

“Berserker’s Prey” by Fred Saberhagen. Copyright © 1967 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Call Me Proteus” by Edward Wellen. Copyright © 1973 by UPD Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Teddi” by Andre Norton. Copyright © 1973 by Western Publishing Company. Reprinted by permission of the Larry Sternig Literary Agency.

“The Gambling Hell and the Sinful Girl” by Katherine MacLean. Copyright © 1974 by the Conde Nast Publications, Inc., reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Virginia Kidd.

“Invasion Report” by Theodore R. Cogswell. Copyright © 1954 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation; copyright renewed © 1982 by Theodore R. Cogswell. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“A Start in Life” by Arthur Sellings. Copyright © 1954 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the Carnell Literary Agency for the author’s estate.

“Big Sword” by Pauline Ashwell. Copyright © 1958 by Street and Smith Publications, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Gift” by Ray Bradbury. Copyright © 1952; renewed © 1980 by Ray Bradbury. Reprinted by permission of Don Congdon Associates, Inc.

Wilderness

by Isaac Asimov

Most species of plants and animals have a restricted range; they are found only in certain places. Sometimes a particular animal may be found only in one remote valley or on one small island; sometimes it roams a large part of a continent.

This was true even for human beings once. The earliest manlike creatures, or hominids, with brains not much larger than a chimpanzee’s, seem to have evolved in east Africa about four million years ago, and remained there for a long time. They spread outward only very slowly, for they were not very brainy. However, evolution continued and, after a time, hominids grew rapidly larger while their brains increased in size even more rapidly.

They gained greater ability to make tools and take care of themselves, and by about half a million years ago, Homo erectus (hominids with brains half the size of ours) had spread to parts of Asia and even to the Indonesian islands.

It was only after human beings like ourselves, Homo sapiens, had evolved, about 50,000 years ago, that there was a still wider spread. About 25,000 years ago (maybe even earlier), human beings traveled from northeastern Asia into North America and from southeastern Asia into Australia. By about 8,000 years ago, they had spread all over those continents. Still later, human beings began to reach the islands that spread out over the Pacific Ocean and to spread into the Arctic coastlands. By A.D. 1000, every part of the land surface that wasn’t covered by ice all year round had a human population.

Even as late as 1500, however, the American continents and Australia were only thinly populated. By then, though, Europeans had learned how to make long voyages and they began flooding over the still empty spaces. By 1900, there were 1½ billion people in the world and there were large cities on all the continents. The population has tripled since then and stands at 4½ billion, so that human beings are the only species whose range is the entire Earth.

There are still large regions we can call wilderness— that is, places that don’t feel the touch of human beings much and that are almost in the shape they would be if there were no human beings on Earth. These are shrinking fast, however. The tropical rain forests in South America and elsewhere are being cut down. There are permanent scientific posts on the ice caps in Greenland and Antarctica. Our ships cross all the oceans and our submarines plumb the depths.

To put it bluntly, Earth is overfilled with us. We can reasonably call it overfilled because we are doing it damage. We are crowding into every corner of the planet in such numbers that we are leaving no room for other plants and animals. Hundreds and thousands of species may be driven into extinction, and life on Earth will lose much of its color and variety. We may even find out too late that some of the species that have vanished were very important to the web of life and that their loss will create problems for us.

Then, too, all the billions of us are straining Earth’s capacity to grow enough food, while our busy activities, whether industrial or biological, are pouring more and more poisons into the air, water and soil so that Earth is steadily becoming a less livable planet.

There is psychological damage, too. In previous centuries, when people felt oppressed, when they felt that they had no security, no future, and that there would be nothing for their children either, they could pack their belongings and move on to the next valley—or cross a mountain range—or an ocean. They could find new land on which to make a new beginning. Millions of Europeans came to the American continents with that hope. In the latter half of the 1800’s, millions of people from the eastern United States traveled westward for that reason.

In the past, there was always a frontier, beyond which was a wilderness to be tamed. Now there are no new lands on Earth, no frontier, no wilderness. Every place belongs to someone and you can no longer simply take to the road and find a new world for yourself if you feel your life is miserable and meaningless. Even if you imagine life in Greenland or Antarctica or under the sea, there is still the fact that the vast crowds of people are damaging the planet and finding room for additional crowds will just create more problems.

This feeling of being imprisoned and of having no escape may account for many of the troubles that plague us today, from drugs to terrorism.

Except that there is a wilderness, new lands, new resources, new space, if we wish to take advantage of it.

We simply need to get off Earth. We need to expand our range again, but instead of crossing a desert or an ocean to do it, we will go straight up. Up there is an endless wilderness in which to build homes and, in doing so, we can even make life better on old, crowded Earth.

We can get a new and endless supply of energy directly from the Sun without the interference of an atmosphere that absorbs much of the energy, without clouds that block the energy, and without a night that keeps the Sun hidden half the time.

We can set up mining stations on the Moon to supply the metals, glass, concrete, and oxygen out of which

to build laboratories in space, and observatories, and factories. Earth’s industrial machinery, automated and robotified, might be lifted little by little into orbit, so that it will no longer pollute Earth. Its wastes will escape into space where they will be swept away by the Solar wind.

Homes can be built in space; whole towns; structures in which ten thousand people can live in carefully engineered environments that will be very much like Earth except that there will be no storms, no temperature extremes, no dirt-producing industries.

The people living in space will be used to space and to space travel. They will be the new pioneers. They will travel to the asteroids to find new resources and new homes. They will settle the whole Solar system. And finally, they will find a way to the stars. . . . And among them, of course, will be children.

Here, then, is a collection of stories dealing with young star travelers, helping to build new homes for humanity.

"If I Forget Thee, Oh Earth..."

by Arthur C. Clarke

This is a story of hope, lunacy, and the big blue marvel.

* * *

When Marvin was ten years old, his father took him through the long, echoing corridors that led up through Administration and Power, until at last they came to the uppermost levels of all and were among the swiftly growing vegetation of the Farmlands. Marvin liked it here: it was fun watching the great, slender plants creeping with almost visible eagerness toward the sunlight as it filtered down through the plastic domes to meet them. The smell of life was everywhere, awakening inexpressible longings in his heart: no longer was he breathing the dry, cool air of the residential levels, purged of all smells but the faint tang of ozone. He wished he could stay here for a little while, but Father would not let him. They went onward until they had reached the entrance to the Observatory, which he had never visited: but they did not stop, and Marvin knew with a sense of rising excitement that there could be only one goal left. For the first time in his life, he was going Outside.

There were a dozen of the surface vehicles, with their wide balloon tires and pressurized cabins, in the great servicing chamber. His father must have been expected, for they were led at once to the little scout car waiting by the huge circular door of the airlock. Tense with expectancy, Marvin settled himself down in the cramped cabin while his father started the motor and checked the controls. The inner door of the lock slid open and then closed behind them: he heard the roar of the great air pumps fade slowly away as the pressure dropped to zero. Then the “Vacuum” sign flashed on, the outer door parted, and before Marvin lay the land which he had never yet entered.

He had seen it in photographs, of course: he had watched it imaged on television screens a hundred times. But now it was lying all around him, burning beneath the fierce sun that crawled so slowly across the jet-black sky. He stared into the west, away from the blinding splendor of the sun—and there were the stars, as he had been told but had never quite believed. He gazed at them for a long time, marveling that anything could be so bright and yet so tiny. They were intense unscintillating points, and suddenly he remembered a rhyme he had once read in one of his father’s books:

Twinkle, twinkle, little star,

How I wonder what you are.

Well, he knew what the stars were. Whoever asked that question must have been very stupid. And what did they mean by “twinkle”? You could see at a glance that all the stars shone with the same steady, unwavering light. He abandoned the puzzle and turned his attention to the landscape around him.

They were racing across a level plain at almost a hundred miles an hour, the great balloon tires sending up little spurts of dust behind them. There was no sign of the Colony: in the few minutes while he had been gazing at the stars, its domes and radio towers had fallen below the horizon. Yet there were other indications of man’s presence, for about a mile ahead Marvin could see the curiously shaped structures clustering round the head of a mine. Now and then a puff of vapor would emerge from a squat smokestack and would instantly disperse.

They were past the mine in a moment: Father was driving with a reckless and exhilarating skill as if—it was a strange thought to come into a child’s mind— he were trying to escape from something. In a few minutes they had reached the edge of the plateau on which the Colony had been built. The ground fell sharply away beneath them in a dizzying slope whose lower stretches were lost in shadow. Ahead, as far as the eye could reach, was a jumbled wasteland of craters, mountain ranges, and ravines. The crests of the mountains, catching the low sun, burned like islands of fire in a sea of darkness: and above them the stars still shone as steadfastly as ever.

There could be no way forward—yet there was. Marvin clenched his fists as the car edged over the slope and started the long descent. Then he saw the barely visible track leading down the mountainside, and relaxed a little. Other men, it seemed, had gone this way before.

Night fell with a shocking abruptness as they crossed the shadow line and the sun dropped below the crest of the plateau. The twin searchlights sprang into life, casting blue-white bands on the rocks ahead, so that there was scarcely need to check their speed. For hours they drove through valleys and past the foot of mountains whose peaks seemed to comb the stars, and sometimes they emerged for a moment into the sunlight as they climbed over higher ground.

And now on the right was a wrinkled, dusty plain, and on the left, its ramparts and terraces rising mile after mile into the sky, was a wall of mountains that marched into the distance until its peaks sank from sight below the rim of the world. There was no sign that men had ever explored this land, but once they passed the skeleton of a crashed rocket, and beside it a stone cairn surmounted by a metal cross.

It seemed to Marvin that the mountains stretched on forever: but at last, many hours later, the range ended in a towering, precipitous headland that rose steeply from a cluster of little hills. They drove down into a shallow valley that curved in a great arc toward the far side of the mountains: and as they did so, Marvin slowly realized that something very strange was happening in the land ahead.

The sun was now low behind the hills on the right: the valley before them should be in total darkness. Yet it was awash with a cold white radiance that came spilling over the crags beneath which they were driving. Then, suddenly, they were out in the open plain, and the source of the light lay before them in all its glory.

It was very quiet in the little cabin now that the motors had stopped. The only sound was the faint whisper of the oxygen feed and an occasional metallic crepitation as the outer walls of the vehicle radiated away their heat. For no warmth at all came from the great silver crescent that floated low above the far horizon and flooded all this land with pearly light. It was so brilliant that minutes passed before Marvin could accept its challenge and look steadfastly into its glare, but at last he could discern the outlines of continents, the hazy border of the atmosphere, and the white islands of cloud. And even at this distance, he could see the glitter of sunlight on the polar ice.

It was beautiful, and it called to his heart across the abyss of space. There in that shining crescent were all the wonders that he had never known—the hues of sunset skies, the moaning of the sea on pebbled shores, the patter of falling rain, the unhurried benison of snow. These and a thousand others should have been his rightful heritage, but he knew them only from the books and ancient records, and the thought filled him with the anguish of exile.

Why could they not return? It seemed so peaceful beneath those lines of marching cloud. Then Marvin, his eyes no longer blinded by the glare, saw that the portion of the disk that should have been in darkness was gleaming faintly with an evil phosphorescence: and he remembered. He was looking upon the funeral pyre of a world—upon the radioactive aftermath of Armageddon. Across a quarter of a million miles of space, the glow of dying atoms was still visible, a perennial reminder of the ruinous past. It would be centuries yet before that deadly glow died from the rocks and life could return again to fill that

silent, empty world.

And now Father began to speak, telling Marvin the story which until this moment had meant no more to him than the fairy tales he had once been told. There were many things he could not understand: it was impossible for him to picture the glowing, multicolored pattern of life on the planet he had never seen. Nor could he comprehend the forces that had destroyed it in the end, leaving the Colony, preserved by its isolation, as the sole survivor. Yet he could share the agony of those final days, when the Colony had learned at last that never again would the supply ships come flaming down through the stars with gifts from home. One by one the radio stations had ceased to call: on the shadowed globe the lights of the cities had dimmed and died, and they were alone at last, as no men had ever been alone before, carrying in their hands the future of the race.

Then had followed the years of despair, and the long-drawn battle for survival in this fierce and hostile world. That battle had been won, though barely: this little oasis of life was safe against the worst that Nature could do. But unless there was a goal, a future toward which it could work, the Colony would lose the will to live, and neither machines nor skill nor science could save it then.

So, at last, Marvin understood the purpose of this pilgrimage. He would never walk beside the rivers of that lost and legendary world, or listen to the thunder raging above its softly rounded hills. Yet one day— how far ahead?—his children’s children would return to claim their heritage. The winds and the rains would scour the poisons from the burning lands and carry them to the sea, and in the depths of the sea they would waste their venom until they could harm no living things. Then the great ships that were still waiting here on the silent, dusty plains could lift once more into space, along the road that led to home.

That was the dream: and one day, Marvin knew with a sudden flash of insight, he would pass it on to his own son, here at this same spot with the mountains behind him and the silver light from the sky streaming into his face.