Short Stories Vol.1

Isaac Asimov

Short Stories Vol.1

Isaac Asimov

Complete Stories

By Isaac Asimov

FOUNDATION, DOUBLEDAY, and the portrayal of the letter F are trademarks of Doubleday, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

All of the characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This volume contains the complete contents of the previously published collections Earth Is Room Enough, Nine Tomorrows, and Nightfall and Other Stories.

This edition copyright (c) 1990 by Nightfall, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

ISBH 0-385-41606-7

Contents

Introduction vii

The Dead Past 3

The Foundation of S.F. Success 41

Franchise 43

Gimmicks Three 57

Kid Stuff 62

The Watery Place 73

Living Space 77

The Message 89

Satisfaction Guaranteed 91

Hell-Fire 104

The Last Trump 106

The Fun They Had 120

Jokester 123

The Immortal Bard 135

Someday 138

The Author's Ordeal 146

Dreaming Is a Private Thing 149

Profession 162

The Feeling of Power 208

The Dying Night 217

I'm in Marsport Without Hilda 239

The Gentle Vultures 250

All the Troubles of the World 263

Spell My Name with an S 277

The Last Question 290

The Ugly Little Boy 301

Nightfall 334

Green Patches 363

Hostess 376

"Breeds There a Man . . . ?" 408

C-Chute 438

"In a Good Cause-" 468

What If- 489

Sally 500

Flies 515

"Nobody Here but-" 521

It's Such a Beautiful Day 531

Strikebreaker 550

Insert Knob A in Hole B 561

The Up-to-Date Sorcerer 563

Unto the Fourth Generation 575

What Is This Thing Called Love? 582

The Machine That Won the War 593

My Son, the Physicist 598

Eyes Do More than See 602

Segregationist 605

I Just Make Them Up, See! 610

Rejection Slips 613

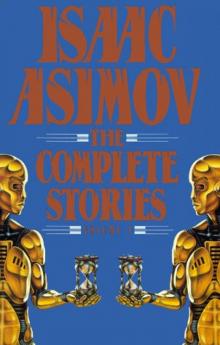

Introduction

I have been writing short stories for fifty-one years and I haven't yet quit. In addition to the hundreds of short stories I have published, there are at least a dozen in press waiting to be published, and two stories written and not yet submitted. So I have by no means retired.

There is, however, no way one can publish short stories for this length of time without understanding that the time left to him is limited. In the words of the song: "Forevermore is shorter than before."

It is time, therefore, for Doubleday to pull the strings together and get all my fiction-short stories and novels, too-into a definitive form and in uniform bindings, both in hard and soft covers.

It may sound conceited of me to say so (I am frequently accused of being conceited), but my fiction generally has been popular from the start and has continued to be well received through the years. To locate any one story, however, that you no longer have and wish you did, or to find one you have heard about but have missed is no easy task. My stories appeared originally in any one of many magazines, the original issues of which are all but unobtainable. They then appeared in any of a multiplicity of anthologies and collections, copies of which are almost as unobtainable.

It is Doubleday's intention to make this multivolume collection definitive and uniform in the hope that the science fiction public, the mystery public (for my many mysteries will also be collected), and libraries as well will seize upon them ravenously and clear their book shelves to make room for Isaac Asimav: The Complete Stories.

We begin in this volume with two of my early collections from the 1950s, Earth Is Room Enough and Nine Tomorrows.

The former includes such favorites of mine as "Franchise," which deals with the ultimate election day; "Living Space," which gives every family a world of its own; "The Fun They Had," my most anthologized story; "Jokester," whose ending I bet you don't anticipate if you've never read the story before; and "Dreaming Is a Private Thing," concerning which Robert A. Heinlein accused me of making money out of my own neuroses.

Nine Tomorrows, the personal favorite of all my collections, contains not one story I don't consider to be excellent examples of my productions of the 1950s. In particular, there is "The Last Question," which, of all the stories I have written, is my absolute favorite.

Then there is "The Ugly Little Boy," my third-favorite story. My tales tend to be cerebral, but I count on this one to bring about a tear or two. (To find out which is the second-favorite of my stories, you'll have to read successive volumes of this collection.) "The Feeling of Power" is another frequently anthologized piece and is rather prophetic, considering it was written before anyone was thinking of pocket computers. "All the Troubles of the World" is a suspense story and "The Dying Night" is a mystery based, alas, on an astronomical "fact" now known to be quite mistaken.

Then there is a later collection included here, Nightfall and Other Stories, which features "Nightfall," a story that many readers and the Science Fiction Writers of America have voted the best science fiction story ever written (I don't think so, but it would be impolite to argue). Other favorites of mine are " 'Breeds There a Man . . . ?' ", which is rather chilling; "Sally," which expresses my feelings about automobiles; "Strikebreaker," which I consider much underappreciated; and "Eyes Do More than See," a short heartstring wrencher.

There'll be more volumes, but begin by reading this one. You will make an old man very happy, you know.

-ISAAC ASIMOV

New York City

March 1990

ISAAC ASIMOV

THE COMPLETE STORIES

Volume 1

The Dead Past

Arnold Potterley, Ph.D., was a Professor of Ancient History. That, in itself, was not dangerous. What changed the world beyond all dreams was the fact that he looked like a Professor of Ancient History.

Thaddeus Araman, Department Head of the Division of Chronoscopy, might have taken proper action if Dr. Potterley had been owner .of a large, square chin, flashing eyes, aquiline nose and broad shoulders.

As it was, Thaddeus Araman found himself staring over his desk at a mild-mannered individual, whose faded blue eyes looked at him wistfully from either side of a low-bridged button nose; whose small, neatly dressed figure seemed stamped "milk-and-water" from thinning brown hair to the neatly brushed shoes that completed a conservative middle-class costume.

Araman said pleasantly, "And now what can I do for you, Dr. Potterley?"

Dr. Potterley said in a soft voice that went well with the rest of him, "Mr. Araman, I came to you because you're top man in chronoscopy."

Araman smiled. "Not exactly. Above me is the World Commissioner of Research and above him is the Secretary-General of the United Nations. And above both of them, of course, are the sovereign peoples of Earth."

Dr. Potterley shook his head. "They're not interested in chronoscopy. I've come to you, sir, because for two years I have been trying to obtain permission to do some time viewing-chronoscopy, that is-in connection with my researches on ancient Carthage. I can't obtain such permission. My research grants are all proper. There is no irregularity in any of my intellectual endeavors and yet-"

Copyright (c) 1956 by St

reet and Smith Publications, Inc.

"I'm sure there is no question of irregularity," said Araman soothingly. He flipped the thin reproduction sheets in the folder to which Potterley's name had been attached. They had been produced by Multivac, whose vast analogical mind kept all the department records. When this was over, the sheets could be destroyed, then reproduced on demand in a matter of minutes.

And while Araman turned the pages, Dr. Potterley's voice continued in a soft monotone.

The historian was saying, "I must explain that my problem is quite an important one. Carthage was ancient commercialism brought to its zenith. Pre-Roman Carthage was the nearest ancient analogue to pre-atomic America, at least insofar as its attachment to trade, commerce and business in general was concerned. They were the most daring seamen and explorers before the Vikings; much better at it than the overrated Greeks.

"To know Carthage would be very rewarding, yet the only knowledge we have of it is derived from the writings of its bitter enemies, the Greeks and Romans. Carthage itself never wrote in its own defense or, if it did, the books did not survive. As a result, the Carthaginians have been one of the favorite sets of villains of history and perhaps unjustly so. Time viewing may set the record straight."

He said much more.

Araman said, still turning the reproduction sheets before him, "You must realize, Dr. Potterley, that chronoscopy, or time viewing, if you prefer, is a difficult process."

Dr. Potterley, who had been interrupted, frowned and said, "I am asking for only certain selected views at times and places I would indicate."

Araman sighed. "Even a few views, even one ... It is an unbelievably delicate art. There is the question of focus, getting the proper scene in view and holding it. There is the synchronization of sound, which calls for completely independent circuits."

"Surely my problem is important enough to justify considerable effort."

"Yes, sir. Undoubtedly," said Araman at once. To deny the importance of someone's research problem would be unforgivably bad manners. "But you must understand how long-drawn-out even the simplest view is. And there is a long waiting line for the chronoscope and an even longer waiting line for the use of Multivac which guides us in our use of the controls."

Potterley stirred unhappily. "But can nothing be done? For two years-"

"A matter of priority, sir. I'm sorry. . . . Cigarette?"

The historian started back at the suggestion, eyes suddenly widening as he stared at the pack thrust out toward him. Araman looked surprised, withdrew the pack, made a motion as though to take a cigarette for himself and thought better of it.

Potterley drew a sigh of unfeigned relief as the pack was put out of sight.

He said, "Is there any way of reviewing matters, putting me as far forward as possible. I don't know how to explain-"

Araman smiled. Some had offered money under similar circumstances which, of course, had gotten them nowhere, either. He said, "The decisions on priority are computer-processed. I could in no way alter those decisions arbitrarily."

Potterley rose stiffly to his feet. He stood five and a half feet tall. "Then, good day, sir."

"Good day, Dr. Potterley. And my sincerest regrets."

He offered his hand and Potterley touched it briefly.

The historian left, and a touch of the buzzer brought Araman's secretary into the room. He handed her the folder.

"These," he said, "may be disposed of."

Alone again, he smiled bitterly. Another item in his quarter-century's service to the human race. Service through negation.

At least this fellow had been easy to dispose of. Sometimes academic pressure had to be applied and even withdrawal of grants.

Five minutes later, he had forgotten Dr. Potterley. Nor, thinking back on it later, could he remember feeling any premonition of danger.

During the first year of his frustration, Arnold Potterley had experienced only that-frustration. During the second year, though, his frustration gave birth to an idea that first frightened and then fascinated him. Two things stopped him from trying to translate the idea into action, and neither barrier was the undoubted fact that his notion was a grossly unethical one.

The first was merely the continuing hope that the government would finally give its permission and make it unnecessary for him to do anything more. That hope had perished finally in the interview with Araman just completed.

The second barrier had been not a hope at all but a dreary realization of his own incapacity. He was not a physicist and he knew no physicists from whom he might obtain help. The Department of Physics at the university consisted of men well stocked with grants and well immersed in specialty. At best, they would not listen to him. At worst, they would report him for intellectual anarchy and even his basic Carthaginian grant might easily be withdrawn.

That he could not risk. And yet chronoscopy was the only way to carry on his work. Without it, he would be no worse off if his grant were lost.

The first hint that the second barrier might be overcome had come a week earlier than his interview with Araman, and it had gone unrecognized at the time. It had been at one of the faculty teas. Potterley attended these sessions unfailingly because he conceived attendance to be a duty, and he took his duties seriously. Once there, however, he conceived it to be no responsibility of his to make light conversation or new friends. He sipped abstemiously at a drink or two, exchanged a polite word with the dean or

such department heads as happened to be present, bestowed a narrow smile on others and finally left early.

Ordinarily, he would have paid no attention, at that most recent tea, to a young man standing quietly, even diffidently, in one corner. He would never have dreamed of speaking to him. Yet a tangle of circumstance persuaded him this once to behave in a way contrary to his nature.

That morning at breakfast, Mrs. Potterley had announced somberly that once again she had dreamed of Laurel; but this time a Laurel grown up, yet retaining the three-year-old face that stamped her as their child. Potterley had let her talk. There had been a time when he fought her too frequent preoccupation with the past and death. Laurel would not come back to them, either through dreams or through talk. Yet if it appeased Caroline Potterley-let her dream and talk.

But when Potterley went to school that morning, he found himself for once affected by Caroline's inanities. Laurel grown up! She had died nearly twenty years ago; their only child, then and ever. In all that time, when he thought of her, it was as a three-year-old.

Now he thought: But if she were alive now, she wouldn't be three, she'd be nearly twenty-three.

Helplessly, he found himself trying to think of Laurel as growing progressively older; as finally becoming twenty-three. He did not quite succeed.

Yet he tried. Laurel using make-up. Laurel going out with boys. Laurel- getting married!

So it was that when he saw the young man hovering at the outskirts of the coldly circulating group of faculty men, it occurred to him quixotically that, for all he knew, a youngster just such as this might have married Laurel. That youngster himself, perhaps. . . .

Laurel might have met him, here at the university, or some evening when he might be invited to dinner at the Potterleys'. They might grow interested in one another. Laurel would surely have been pretty and this youngster looked well. He was dark in coloring, with a lean intent face and an easy carriage.

The tenuous daydream snapped, yet Potterley found himself staring foolishly at the young man, not as a strange face but as a possible son-in-law in the might-have-been. He found himself threading his way toward the man. It was almost a form of autohypnotism.

He put out his hand. "I am Arnold Potterley of the History Department. You're new here, I think?"

The youngster looked faintly astonished and fumbled with his drink, shifting it to his left hand in order to shake with his right. "Jonas Foster is my name, sir. I'm a new instructor in physics. I'm just starting this semester."

Potterle

y nodded. "I wish you a happy stay here and great success."

That was the end of it, then. Potterley had come uneasily to his senses,

found himself embarrassed and moved off. He stared back over his shoulder once, but the illusion of relationship had gone. Reality was quite real once more and he was angry with himself for having fallen prey to his wife's foolish talk about Laurel.

But a week later, even while Araman was talking, the thought of that young man had come back to him. An instructor in physics. A new instructor. Had he been deaf at the time? Was there a short circuit between ear and brain? Or was it an automatic self-censorship because of the impending interview with the Head of Chronoscopy?

But the interview failed, and it was the thought of the young man with whom he had exchanged two sentences that prevented Potterley from elaborating his pleas for consideration. He was almost anxious to get away.

And in the autogiro express back to the university, he could almost wish he were superstitious. He could then console himself with the thought that the casual meaningless meeting had really been directed by a knowing and purposeful Fate.

Jonas Foster was not new to academic life. The long and rickety struggle for the doctorate would make anyone a veteran. Additional work as a postdoctorate teaching fellow acted as a booster shot.

But now he was Instructor Jonas Foster. Professorial dignity lay ahead. And he now found himself in a new sort of relationship toward other professors.

For one thing, they would be voting on future promotions. For another, he was in no position to tell so early in the game which particular member of the faculty might or might not have the ear of the dean or even of the university president. He did not fancy himself as a campus politician and was sure he would make a poor one, yet there was no point in kicking his own rear into blisters just to prove that to himself.

So Foster listened to this mild-mannered historian who, in some vague way, seemed nevertheless to radiate tension, and did not shut him up abruptly and toss him out. Certainly that was his first impulse.