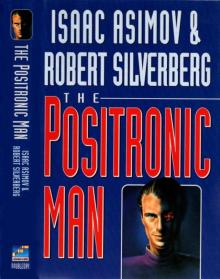

The Positronic Man

Isaac Asimov

The Positronic Man

Isaac Asimov

Robert Silverberg

Isaac Asimov, Robert Silverberg

The Positronic Man

For Janet and Karen — with much love

The tree laws of robotics

1. A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

One

"IF YOU'LL TAKE A SEAT, sir," the surgeon said, gesturing toward the chair in front of his desk. "Please."

"Thank you," said Andrew Martin.

He seated himself calmly. He did everything calmly. That was his nature; it was one part of him that would never change. Looking at him now, one could have no way of knowing that Andrew Martin had been driven to the last resort. But he had been. He had come halfway across the continent for this interview. It represented his only remaining hope of achieving his life's main goal-everything had come down to that. Everything.

There was a smooth blankness to Andrew's face-though a keen observer might well have imagined a hint of melancholy in his eyes. His hair was smooth, light brown, rather fine, and he looked freshly and cleanly shaven: no beard, no mustache, no facial affectations of any sort. His clothes were well made and neat, predominantly a velvety red-purple in color; but they were of a distinctly old-fashioned cut, in the loose, flowing style called "drapery" that had been popular several generations back and was rarely seen these days.

The surgeon's face had a certain blankness about it also: hardly a surprising thing, for the surgeon's face, like all the rest of him, was fashioned of lightly bronzed stainless steel. He sat squarely upright at his imposing desk in the windowless room high over Lake Michigan, looking outward at Andrew Martin with the utmost serenity and poise evident in his glowing eyes. In front of him on the desk was a gleaming brass nameplate that announced his serial number, the usual factory-assigned assortment of letters and numbers.

Andrew Martin paid no attention to that soulless string of characters and digits. Such dreary, mechanistic identity-designations were nothing of any moment to him-not now, not any more, not for a very long time. Andrew felt no need to call the robot surgeon anything but "Doctor."

The surgeon said, "This is all very irregular, you know, sir. Very irregular."

"Yes. I know that," Andrew Martin said.

"I've thought about very little else since this request first came to my attention."

"I sincerely regret any discomfort that it may have caused you."

"Thank you. I am grateful for your concern."

All very formal, very courteous, very useless. They were simply fencing with each other, neither one willing to get down to essentials. And now the surgeon fell silent. Andrew waited for him to proceed. The silence went on and on.

This is getting us nowhere, Andrew told himself.

To the surgeon he said, "The thing that I need to know, Doctor, is how soon the operation can be carried out."

The surgeon hesitated a perceptible moment. Then he said softly, with that certain inalienable note of respect that a robot always used when speaking to a human being, "I am not convinced, sir, that I fully understand how such an operation could be performed, let alone why it should be considered desirable. And of course I still don't know who the subject of the proposed operation is going to be."

There might have been a look of respectful intransigence on the surgeon's face, if the elegantly contoured stainless steel of the surgeon's face had been in any way capable of displaying such an expression-or any expression at all.

It was the turn of Andrew Martin to be silent for a moment, now.

He studied the robot surgeon's right hand-his cutting hand-as it rested on the desk in utter tranquility. It was splendidly designed. The fingers were long and tapering, and they were shaped into metallic looping curves of great artistic beauty, curves so graceful and appropriate to their function that one could easily imagine a scalpel being fitted into them and instantly becoming, at the moment they went into action, united in perfect harmony with the fingers that wielded it: surgeon and scalpel fusing into a single marvelously capable tool.

That was very reassuring, Andrew thought. There would be no hesitation in the surgeon's work, no stumbling, no quivering, no mistakes or even the possibility of a mistake.

Such skill came with specialization, of course-a specialization so fiercely desired by humanity that few robots of the modern era were independently brained any more. The great majority of them nowadays were mere adjuncts of enormously powerful central processing units that had computing capacities far beyond the space limitations of a single robot frame.

A surgeon, too, really needed to be nothing more than a set of sensors and monitors and an array of tool-manipulating devices-except that people still preferred the illusion, if nothing more than that, that they were being operated on by an individual entity, not by a limb of some remote machine. So surgeons-the ones in private practice, anyway-were still independently brained. But this one, brained or not, was so limited in his capacity that he didn't recognize Andrew Martin-had probably never heard of Andrew Martin at all, in fact.

That was something of a novelty for Andrew. He was more than a little famous. He had never asked for his fame, of course-that was not his style-but fame, or at any rate notoriety, had come to him all the same. Because of what he had achieved: because of what he was. Not who, but what.

Instead of replying to what the surgeon had asked him Andrew said, with sudden striking irrelevance, "Tell me something, Doctor. Have you ever thought you would like to be a man?"

The question, startling and strange, obviously took the surgeon aback. He hesitated a moment as though the concept of being a man was so alien to him that it would fit nowhere in his allotted positronic pathways.

Then he recovered his aplomb and replied serenely, "But I am a robot, sir."

"Wouldn't it be better to be a man, don't you think?"

"If I were allowed the privilege of improving myself, sir, I would choose to be a better surgeon. The practice of my craft is the prime purpose of my existence. There is no way I could be a better surgeon if I were a man, but only if I were a more advanced robot. It would please me very much indeed to be a more advanced robot."

"But you would still be a robot, even so."

"Yes. Of course. To be a robot is quite acceptable to me. As I have just explained, sir, in order for one to excel at the extremely difficult and demanding practice of modern-day surgery it is necessary that one be-"

"A robot, yes," said Andrew, with just a note of exasperation creeping into his tone. "But think of the subservience involved, Doctor! Consider: you're a highly skilled surgeon. You deal in the most delicate matters of life and death-you operate on some of the most important individuals in the world, and for all I know you have patients come to you from other worlds as well. And yet-and yet-a robot? You're content with that? For all your skill, you must take orders from anyone, any human at all: a child, a fool, a boor, a rogue. The Second Law commands it. It leaves you no choice. Right this minute I could say, 'Stand up, Doctor,' and you'd have to stand up. 'Put your fingers over your face and wiggle them,' and you'd wiggle. Stand on one leg, sit down on the floor, move right or left, anything I wanted to tell you, and you'd obey. I could order you to disassemble yourself limb by limb, and you would. You, a great surgeon! No choice at all. A human whistles and you hop to his tune. Doesn't it offend you that I have the power to make you do whatever dam

ned thing I please, no matter how idiotic, how trivial, how degrading?"

The surgeon was unfazed.

"It would be my pleasure to please you, sir. With certain obvious exceptions. If your orders should happen to involve my doing any harm to you or any other human being, I would have to take the primary laws of my nature into consideration before obeying you, and in all likelihood I would not obey you. Naturally the First Law, which concerns my duty to human safety, would take precedence over the Second Law relating to obedience. Otherwise, obedience is my pleasure. If it would give you pleasure to require me to do certain acts that you regard as idiotic or trivial or degrading, I would perform those acts. But they would not seem idiotic or trivial or degrading to me."

There was nothing even remotely surprising to Andrew Martin in the things the robot surgeon had said. He would have found it astonishing, even revolutionary, if the robot had taken any other position.

But even so-even so- The surgeon said, with not the slightest trace of impatience in his smooth bland voice, "Now, if we may return to the subject of this extraordinary operation that you have come here to discuss, sir. I can barely comprehend the nature of what you want done. It is hard for me to visualize a situation that would require such a thing. But what I need to know, first of all, is the name of the person upon whom I am asked to perform this operation."

"The name is Andrew Martin," Andrew said. "The operation is to be performed on me."

"But that would be impossible, sir!"

"Surely you'd be capable of it."

"Capable in a technical sense, yes. I have no serious doubt on that score, regardless of what may be asked of me, although in this case there are certain procedural issues that I would have to consider very carefully. But that is beside the point. I ask you please to bear in mind, sir, that the fundamental effect of the operation would be harmful to you."

"That does not matter at all," said Andrew calmly.

"It does to me."

"Is this the robot version of the Hippocratic Oath?"

"Something far more stringent than that," the surgeon said. "The Hippocratic Oath is, of course, a voluntary pledge. But there is, as plainly you must be aware, something innate in my circuitry itself that controls my professional decisions. Above and beyond everything else, I must not inflict damage. I may not inflict damage."

"On human beings, yes."

"Indeed. The First Law says-"

"Don't recite the First Law, Doctor. I know it at least as well as you. But the First Law simply governs the actions of robots toward human beings. I'm not human, Doctor."

The surgeon reacted with a visible twitch of his shoulders and a blinking of his photoelectric eyes. It was as if what Andrew had just said had no meaning for him whatever.

"Yes," said Andrew, "I know that I seem to be quite human, and that what you're experiencing now is the robot equivalent of surprise. Nevertheless I'm telling you the absolute truth. However human I may appear to you, I am simply a robot. A robot, Doctor. A robot is what I am, and nothing more than that. Believe me. And therefore you are free to operate on me. There is nothing in the First Law which prohibits a robot from performing actions on another robot. Even if the action that is performed should cause harm to that robot, Doctor."

Two

IN THE BEGINNING, of course-and the beginning for him was nearly two centuries before his visit to the surgeon's office-no one could have mistaken Andrew Martin for anything but the robot he was.

In that long-ago era when he had first come from the assembly line of United States Robots and Mechanical Men he was as much a robot in appearance as any that had ever existed, smoothly designed and magnificently functional: a sleek mechanical object, a positronic brain encased in a more-or-less humanoid-looking housing made from metal and plastic.

His long slim limbs then were finely articulated mechanisms fashioned from titanium alloys overlaid by steel and equipped with silicone bushings at the joints to prevent metal-to-metal contact. His limb sockets were of the finest flexible polyethylene. His eyes were photoelectric cells that gleamed with a deep red glow. His face-and to call it that was charitable; it was the merest perfunctory sketch of a face-was altogether incapable of expression. His bare, sexless body was unambiguously a manufactured device. All it took was a single glance to see that he was a machine, no more animate, no more human, no more alive, than a telephone or a pocket calculator or an automobile.

But that was in another era, long, long ago.

It was an era when robots were still uncommon sights on Earth-almost the very dawn of the age of robotics, not much more than a generation after the days when the great early roboticists like Alfred Lanning and Peter Bogert and the legendary robopsychologist Susan Calvin had done their historic work, developing and perfecting the principles by which the first positronic robots had come into being.

The aim of those pioneers had been to create robots capable of taking up many of the dreary burdens that human beings had for so long been compelled to bear. And that was part of the problem that the roboticists faced, in those dawning days of the science of artificial life late in the Twentieth Century and early in the Twenty-First: the unwillingness of a great many human beings to surrender those burdens to mechanical substitutes. Because of that unwillingness, strict laws had been passed in virtually every country-the world was still broken up into a multitude of nations, then-against the use of robot labor on Earth.

By the year 2007 they had been banned entirely everywhere on the planet, except for scientific research under carefully controlled conditions. Robots could be sent into space, yes, to the ever-multiplying industrial factories and exploratory stations off Earth: let them cope with the miseries of frigid Ganymede and torrid Mercury, let them put up with the inconveniences of scrabbling around on the surface of Luna, let them run the bewildering risks of the early Jump experiments that would eventually give mankind the hyperspace road to the stars.

But robots in free and general use on Earth-occupying precious slots in the labor force that would otherwise be available for actual naturally-born flesh-and-blood human beings-no! No! No robots wanted around here!

Well, that had eventually begun to change, of course. And the most dramatic changes had begun to set in around the time that Robot NDR-113, who would someday be known as Andrew Martin, had been undergoing assembly at the main Northern Region factory of United States Robots and Mechanical Men.

One of the factors bringing about the gradual breakdown of the antirobot prejudices on Earth at that time was simple public relations. United States Robots and Mechanical Men was not only a scientifically adept organization, it knew a thing or two about the importance of maintaining its profitability, too. So it had found ways, quiet and subtle and effective, of chipping away at the Frankenstein myth of the robot, the concept of the mechanical man as the dreaded shambling Golem.

Robots are here for our convenience, the U.S.R.M.M. public relations people said. Robots are here to help us. Robots are not our enemies. Robots are perfectly safe, safe beyond any possibility of doubt.

And-because in fact all those things were actually true-people began to accept the presence of robots among them. They did so grudgingly, in the main. Many people-most, perhaps-were still uncomfortable with the whole idea of robots; but they recognized the need for them and they could at least tolerate having them around, so long as tight restrictions on their use continued to be applied.

There was need for robots, like it or not, because the population of Earth had started to dwindle about that time. After the long anguish that was the Twentieth Century, a time of relative tranquility and harmony and even rationality-a certain degree of that, anyway-had begun to settle over the world. It became a quieter, calmer, happier place. There were fewer people by far, not because there had been terrible wars and plagues, but because families now tended to be smaller, giving preference to quality over quantity. Migration to the newly settled worlds of space was draining off some of Earth's population

also-migration to the extensive network of underground settlements on the Moon, to the colonies in the asteroid belt and on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, and to the artificial worlds in orbit around Earth and Mars.

So there was no longer so much excitement over the possibility of losing one's job to a robot. The fear of job shortages on Earth had given way to the problem of labor shortages. Suddenly the robots that once had been looked upon with such uneasiness, fear, and even hatred became necessary to maintain the welfare of a world that had every material advantage but didn't have enough of a population left to sweep the streets, drive the taxis, cook the meals, stoke the furnaces.

It was in this new era of diminishing population and increasing prosperity that NDR-113-the future Andrew Martin-was manufactured. No longer was the use of robots illegal on Earth; but strict regulations still applied, and they were still far from everyday sights. Especially robots who were programmed for ordinary household duties, which was the primary use that Gerald Martin had in mind for NDR-113.

Hardly anyone in those days had a robot servant around the house. It was too frightening an idea for most people-and too expensive, besides.

But Gerald Martin was hardly just anyone. He was a member of the Regional Legislature, a powerful member at that, Chairman of the Science and Technology Committee: a man of great presence and authority, of tremendous force of mind and character. What Gerald Martin set out to achieve, Gerald Martin inevitably succeeded in achieving. And what Gerald Martin chose to possess, Gerald Martin would invariably come to possess. He believed in robots: he knew that they were an inevitable development, that they would ultimately become inextricably enmeshed in human society at every level.

And so-utilizing his position on the Science and Technology Committee to the fullest-he had been able to arrange for robots to become a part of his private life, and that of his family. For the sake of gaining a deeper understanding of the robot phenomenon, he had explained. For the sake of helping his fellow members of the Regional Legislature to discover how they might best grapple with the problems that the coming era of robotic ubiquity would bring. Bravely, magnanimously, Gerald Martin had offered himself as an experimental subject and had volunteered to take a small group of domestic robots into his own home.