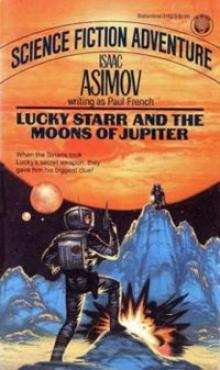

Lucky Starr The And The Moons of Jupiter ls-5

Isaac Asimov

Lucky Starr The And The Moons of Jupiter

( Lucky Starr - 5 )

Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov

Lucky Starr The And The Moons of Jupiter

Preface

Back in the 1950s, I wrote a series of six derring-do novels about David "Lucky" Starr and his battles against malefactors within the Solar System. Each of the six took place in a different region of the system and in each case I made use of the astronomical facts-as they were then known.

Now more than a quarter-century later, these novels are being published in new editions; but what a quarter-century it has been! More has been learned about the worlds of our Solar System in this last quarter-century than in all the thousands of years that went before.

LUCKY STARR: AND THE MOONS OF JUPITER was written in 1956. In late 1973, however, the Jupiter-probe, Pioneer X, passed by Jupiter and recorded an enormous magnetic field containing dense concentrations of charged particles. The large satellites of Jupiter are buried in that field and the intensity of radiation would certainly make it difficult or even impossible for manned ships to maneuver in their neighborhood.

Lucky's trip through the satellite system would have to be adjusted to take the intense radiation into account if I were writing the book today. And in 1974, a 13th satellite of Jupiter, was discovered, a very small one only a few miles across, with an orbit quite similar to that of Jupiter-IX. I'd have mentioned it if I were doing the book now.

I hope my Gentle Readers enjoy the book anyway, as an adventure story, but please don't forget that the advance of science can outdate even the most conscientious science-fiction writer and that my astronomical descriptions are no longer accurate in all respects.

Isaac Asimov

1. Trouble on Jupiter Nine

Jupiter was almost a perfect circle of creamy light, half the apparent diameter of the moon as seen from Earth, but only one seventh as brightly lit because of its great distance from the sun. Even so, it was a beautiful and impressive sight.

Lucky Starr gazed at it thoughtfully. The lights in the control room were out and Jupiter was centered on the visiplate, its dim light making Lucky and his companion something more than mere shadows. Lucky said, "If Jupiter were hollow, Bigman, you could dump thirteen hundred planets the size of Earth into it and still not quite fill it up. It weighs more than all the other planets put together."

John Bigman Jones, who allowed no one to call him anything but Bigman, and who was five feet two inches tall if he stretched a little, disapproved of anything that was big, except Lucky. He said, "And what good is all of it? No one can land on it. No one can come near it."

"We'll never land on it, perhaps," said Lucky, "but we'll be coming close to it once the Agrav ships are developed."

"With the Sirians on the job," said Bigman, scowling in the gloom, "it's going to take ms to make sure that happens."

"Well, Bigman, we'll see."

Bigman pounded his small right fist into the open palm of his other hand. "Sands of Mars, Lucky, how long do we have to wait here?"

They were in Lucky's ship, the Shooting Starr, which was in an orbit about Jupiter, having matched velocities with Jupiter Nine, the giant planet's outermost satellite of any size.

That satellite hung stationary a thousand miles away. Officially, its name was Adrastea, but except for the largest and closest, Jupiter's satellites were more popularly known by numbers. Jupiter Nine was only eighty-nine miles in diameter, merely an asteroid, really, but it looked larger than distant Jupiter, fifteen million miles away. The satellite was a craggy rock, gray and forbidding in the sun's weak light, and scarcely worth interest. Both Lucky and Bigman had seen a hundred such sights in the asteroid belt.

In one way, however, it was different. Under its skin a thousand men and billions of dollars labored to produce ships that would be immune to the effects of gravity.

Nevertheless, Lucky preferred watching Jupiter. Even at its present distance from the ship (actually three fifths of the distance of Venus from Earth at then closest approach), Jupiter showed a disc large enough to reveal its colored zones to the naked eye. They showed in fault pink and greenish-blue, as though a child had dipped Ms fingers in a watery paint and trailed them across Jupiter's image

Lucky almost forgot the deadliness of Jupiter in its beauty. Bigman had to repeat his question in a louder voice.

"Hey, Lucky, how long do we have to wait here?"

"You know the answer to that, Bigman. Until Commander Donahue comes to pick us up."

"I know that part. What I want to know is why we have to wait for him."

"Because he's asked us to."

"Oh, he has. Who does the cobber think he is?"

"The head of the Agrav project," Lucky said patiently.

"You don't have to do what he says, you know, even if he is."

Bigman had a sharp and deep realization of Lucky's powers. As full member of the Council of Science, that selfless and brilliant organization that fought the enemies of Earth within and without the solar system, Lucky Starr could write his own ticket even against the most high-ranking.

But Lucky was not quite ready to do that. Jupiter was a known danger, a planet of poison and unbearable gravity; but the situation on Jupiter Nine was more dangerous still because the exact points of danger were unknown-and until Lucky could know a bit more, he was picking his way forward carefully.

"Be patient, Bigman," he said.

Bigman grumbled and flipped the lights on. "We're not staring at Jupiter all day, are we?"

He walked over to the small Venusian creature bobbing up and down in its enclosed water-filled cage in the corner of the pilot room. He peered fondly down at it, his wide mouth grinning with pleasure. The V-frog always had that effect on Bigman, or indeed, on anyone.

The V-frog was a native of the Venusian oceans, [1] a tiny thing that seemed, at times, all eyes and feet. Its body was green and froglike and but six inches long. His twa big eyes protruded like gleaming blackberries, and its sharp, strongly curved beak opened and closed at irregular intervals. At the moment its six legs were retracted, so that the V-frog hugged the bottom of its cage, but when Bigman tapped the top cover, they unfolded like a carpenter's rule and became stilts. ^

It was an ugly little thing but Bigman loved it when he was near it. He couldn't help it. Anyone else would feel the same. The V-frog saw to that.

Carefully Bigman checked the carbon-dioxide cylinder that kept the V-frog's water well saturated and healthful and made sure that the water temperature in the cage was at ninety-five. (The warm oceans of Venus were bathed by and saturated with an atmosphere of nitrogen and carbon dioxide. Free oxygen, nonexistent on Venus except in the man-made domed cities at the bottom of its ocean shallows, would have been most uncomfortable for the V-frog.)

Bigman said, "Do you think the weed supply is enough?" and as though the V-frog heard the remark, its beak snipped a green tendril off the native Venusian weed that spread through the cage, and chewed slowly.

Lucky said, "It will hold till we land on Jupiter Nine," and then both men looked up sharply as the receiving signal sounded its unmistakable rasp.

A stern, aging face was centered on the visiplate after Lucky's fingers had quickly made the necessary adjustments.

"Donahue at this end," said a voice briskly.

"Yes, Commander," said Lucky. "We've been waiting for you."

"Clear locks for tube attachment, then."

On the commander's face, written in an expression as clear as though it consisted of letters the size of Class I meteors, was worry-trouble and worry.

Lucky had grown ac

customed to just that expression on men's faces in these past weeks. On Chief Councilman Hector Conway's for instance. To the chief councilman, Lucky was almost a son and the older man felt no need to assume any pretense of confidence.

Conway 's rosy face, usually amiable and self-assured under its crown of pure white hair, was set in a troubled frown. ''I've been waiting for a chance to talk to you for months."

'Trouble?" Lucky asked quietly. He had just returned from Mercury less than a month earlier, and the intervening time had been spent in his New York apartment. "I didn't get any calls from you."

"You earned your vacation," Conway said gruffly. "I wish I could afford to let it continue longer."

"Just what is it, Uncle Hector?"

The chief councilman's old eyes stared firmly into those of the tall, lithe youngster before him and seemed to find comfort in those calm, brown ones. "Sirius!" he said.

Lucky felt a stir of excitement within him. Was it the great enemy at last?

It had been centuries since the pioneering expedi- tions from Earth had colonized the planets of the nearer stars. New societies had grown up on those worlds outside the solar system. Independent societies that scarcely remembered their Earthly origin.

The Sirian planets formed the oldest and strongest of those societies. The society had grown up on new worlds where an advanced science was brought to bear on untapped resources. It was no secret that the Sirianss strong in the belief that they represented the best of mankind, looked forward to the time when they might rule all men everywhere; and that they considered Earth, the old mother world, their greatest enemy.

In the past they had done what they could to support the enemies of Earth at home [2] but never yet had they felt quite strong enough to risk open war.

But now?

"What' s this about Sinus?" asked Lucky.

Conway leaned back. His fingers drummed lightly on the table. He said, "Sirius grows stronger each year. We know that But their worlds are underpopulated; they have only a few millions. We still have more human beings in our solar system than exist in all the galaxy besides. We have more ships and more scientists; we still have the edge. But, by Space, we won't keep that edge if things keep on as they've been going."

"In what way?"

"The Sirians are finding out things. The Council has definite evidence that Sirius is completely up-to-date on our Agrav research."

"What!" Lucky was startled. There were few things more top-secret than the Agrav project. One of the reasons actual construction had been confined to one of the outer satellites of Jupiter had been for the sake of better security. "Great Galaxy, how has that happened?"

Conway smiled bitterly. "That is indeed the question. How has that happened? All sorts of material are leaking out to them, and we don't know how. The Agrav data is most critical. We've tried to stop it. There isn't a man on the project that hasn't been thoroughly checked for loyalty. There isn't a precaution we haven't taken. Yet material still leaks. We've planted false data and that's gone out. We know it has from our own Intelligence information. We've planted data in such ways that it couldn't go out, and yet it has."

"How do you mean couldn't go out?"

"We scattered it so that no one man-in fact, no half dozen men-could possibly be aware of it all. Yet it went. It would mean that a number of men would have to be co-operating in espionage and that's just unbelievable."

"Or that some one man has access everywhere," said Lucky.

"Which is just as impossible. It must be something new, Lucky. Do you see the implication? If Sirius has learned a new way of picking our brains, we're no longer safe. We could never organize a defense against them. We could never make plans against them."

"Hold it, Uncle Hector. Great Galaxy, give yourself a minute. What do you mean when you say they're picking our brains?" Lucky fixed his glance keenly on the older man.

The chief councilman flushed. "Space, Lucky, I'm getting desperate. I can't see how else this can be done. The Sirians must have developed some form of mind reading, of telepathy."

"Why be embarrassed at suggesting that? I suppose it's possible. We know of one practical means of telepathy at least. The Venusian V-frogs."

"All right," said Conway. "I've thought of that, too, but they don't have Venusian V-frogs. I know what's been going on in V-frog research. It takes thousands of them working in combination to make telepathy possible. To keep thousands of them anywhere but on Venus would be awfully difficult, and easily detectable, too. And without V-frogs, there is no way of managing telepathy."

"No way we've worked out," Lucky said softly, "so far. It is possible that the Sirians are ahead of us in telepathy research."

"Without V-frogs?"

"Even without V-frogs."

"I don't believe it," Conway cried violently. "I can't believe that the Sirians can have solved any problem that has left the Council of Science so completely helpless."

Lucky almost smiled at the older man's pride in the organization, but had to admit that there was something more than merely pride there. The Council of Science represented the greatest collection of intellect the galaxy had ever seen, and for a century not one sizable piece of scientific advance anywhere in the Galaxy had come anywhere but from the Council.

Nevertheless Lucky couldn't resist a small dig. He said, "They're ahead of us in robotics."

"Not really," snapped Conway. "Only in its applications. Earthmen invented the positronic brain that made the modern mechanical man possible. Don't forget that. Earth can take the credit for all the basic developments. It's just that Sinus builds more robots and," he hesitated, "has perfected some of the engineering details."

"So I found out on Mercury," Lucky said grimly. [3]

"Yes, I know, Lucky. That was dreadfully close."

"But it's over. Let's consider what's facing us now. The situation is this: Sinus is conducting successful espionage and we can't stop them."

"Yes."

"And the Agrav project is most seriously affected."

"Yes."

"And I suppose, Uncle Hector, that what you want me to do is to go out to Jupiter Nine and see if I can learn something about this."

Conway nodded gloomily. "It's what I'm asking you to do. It's unfair to you. I've gotten into the habit of thinking of you as my ace, my trump card, a man I can give any problem and be sure it will be solved. Yet what can you do here? There's nothing Council hasn't tried and we've located no spy and no method of espionage. What more can we expect of you?"

"Not of myself alone. I'll have help."

"Bigman?" The older man couldn't help smiling.

"Not Bigman alone. Let me ask you a question. To your knowledge, has any information concerning our V-frog research on Venus leaked out to the Sirians?"

"No," said Conway. "None has, to my knowledge."

"Then I'll ask to have a V-frog assigned to me."

"A V-frog! One V-frog?"

"That's right."

"But what good win that do you? The mental field of a single V-frog is terribly weak. You won't be able to read minds."

"True, but I might be able to catch whiffs of strong emotion."

Conway said thoughtfully, "You might do that. But what good would that do?"

''I'm not sure yet. Still, it will be an advantage previous investigators haven't had. An unexpected emotional surge on the part of someone there might help me, might give me grounds for suspicion, might point the direction for further investigation. Then, too-"

"Yes?"

"If someone possesses telepathic power, developed either naturally or by use of artificial aids, I might detect something much stronger than just a whiff of emotion. I might detect an actual thought, some distinct thought, before the individual learns enough from my mind to shield his thoughts. You see what I mean?"

"He could detect your emotions, too."

"Theoretically, yes, but I would be listening for emotion, so to speak. He would not."

Conway

's eyes brightened. "It's a feeble hope, but, by Space, it's a hope! I'll get you your V-frog… But one thing, David," and it was only at moments of deep concern that he used Lucky's real name, the one by which the young councilman had been known all through childhood-"I want you to appreciate the importance of this. If we don't find out what the Sirians are doing, it means they are really ahead of us at last. And that means war can't be delayed much longer. War or peace hangs on this."

"I know," said Lucky softly.

2. The Commander Is Angry

And so it came about that Lucky Starr, Earthman, and his small friend, Bigman Jones, born and bred on Mars, [4] traveled beyond the asteroid belt and into the outer reaches of the solar system. And it was for this reason also that a native of Venus, not a man at all, but a small mind-reading and mind-influencing animal, accompanied them.

They hovered, now, a thousand miles above Jupiter Nine and waited as a flexible conveyer tube was made fast between the Shooting Starr and the commander's ship. The tube linked air lock to air lock and formed a passageway which men could use in going from one ship to the other without having to put on a space suit. The air of both ships mingled, and a man used to space, taking advantage of the absence of gravity, could shoot along the tube after a single initial push and guide himself along those places where the tube curved with the gentle adjusting force of a well-placed elbow.

The commander's hands were the first part of him visible at the lock opening. They gripped the lip of the opening and pushed in such a way that the commander himself leapfrogged out and came down in the Shooting Starr's localized artificial gravity field (or pseudo-grav field, as it was usually termed) with scarcely a stagger. It was neatly done, and Bigman, who had high standards indeed for all forms of spacemen's techniques, nodded in approval.

"Good day, Councilman Starr," said Donahue gruffly. It was always a matter of difficulty whether to say "good morning," "good afternoon," or "good evening" in space, where, strictly speaking, there was neither morning, afternoon, nor evening. "Good day" was the neutral term usually adopted by spacemen.