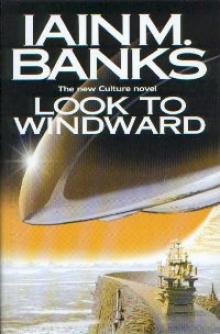

Look to Windward c-7

Iain M. Banks

Look to Windward

( Culture - 7 )

Iain M. Banks

It was one of the less glorious incidents of the Idiran wars that led to the destruction of two suns and the billions of lives they supported. Now, 800 years later, the light from the first of those deaths has reached the Culture’s Masaq’ Orbital. A Chelgrian emissary is dispatched to the Culture.

Look to Windward

by Iain M. Banks

Gentile or Jew

O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

—T.S. Eliot, “The Waste Land”, IV

Prologue

Near the time we both knew I would have to leave him, it was hard to tell which flashes were lightning and which came from the energy weapons of the Invisibles.

A vast burst of blue-white light leapt across the sky, making an inverted landscape of the ragged clouds’ undersurface and revealing through the rain the destruction all around us: the shell of a distant building, its interior scooped out by some earlier cataclysm, the tangled remains of rail pylons near the crater’s lip, the fractured service pipes and tunnels the crater had exposed, and the massive, ruined body of the wrecked land destroyer lying half submerged in the pool of filthy water in the bottom of the hole. When the flare died it left only a memory in the eye and the dull flickering of the fire inside the destroyer’s body.

Quilan gripped my hand still tighter. “You should go. Now, Worosei.” Another, smaller flash lit his face and the oil-scummed mud around his waist where it disappeared under the war machine.

I made a show of consulting my helm’s read-out. The ship’s flyer was on its way back, alone. The display told me that no larger craft was accompanying it, while the lack of any communication on the open channel meant there was no good news to report. There would be no heavy lift, there would be no rescue. I flipped to the close-quarter tactical view. Nothing better to report there. The confused, pulsing schematics indicated there was great uncertainty in the representation (a bad enough sign in itself) but it looked like we were right in the line of the Invisibles’ advance and we would soon be over-run. In ten minutes, maybe. Or fifteen. Or five. That uncertain. Still I smiled as best I could and tried to sound calm.

“I can’t get to anywhere safer until the flyer gets here,” I said quietly. “Neither of us can.” I shifted on the muddy slope, trying to find a better footing. A series of booms shook the air. I crouched over Quilan, protecting his exposed head. I heard debris thudding onto the slope across from us, and something splashed into the water. I glanced at the level of the pool in the bottom of the crater as the waves slapped against the chisel shape of the land destroyer’s fore armour and fell back again. At least the water didn’t seem to be rising any more.

“Worosei,” he said. “I don’t think I’m going anywhere. Not with this thing on top of me. Please. I’m not trying to be heroic and neither should you. Just get out now. Go.”

“There’s still time,” I told him. “We’ll get you out of there. You were always so impatient.” Light pulsed above us again, picking out each lancing drop of rain in the darkness.

“And you were—”

Whatever he was going to say was drowned out by another fusillade of sharp concussions; the noise rolled over us as though the very air was being torn apart.

“Loud night,” I said as I crouched over him again. My ears were ringing. More light flickered to one side and, close up, I could see the pain in his eyes. “Even the weather’s against us, Quilan. Dreadful thunder.”

“That was not thunder.”

“Oh, it was! There! And that is lightning,” I said as I crouched further over him.

“Go. Now, Worosei,” he whispered. “You’re being stupid.”

“I—” I began. Then my rifle slipped from my shoulder and the stock hit him on the forehead. “Ouch,” he said.

“Sorry.” I shouldered the weapon again.

“My fault for losing my helmet.”

“Still,” I slapped one of the sections of track above us, “you gained a land destroyer.”

He started to laugh, then winced. He forced a smile and rested one hand against the surface of one of the vehicle’s guide wheels. “It’s funny,” he said. “I’m not even sure if it’s one of ours or one of theirs.”

“You know,” I said, “neither am I.” I looked up at its ruptured carcass. The fire inside seemed to be spreading; thin blue and yellow flames were starting to show in the hole where the main turret had been.

The crippled land destroyer had kept its tracks on this side as it had half trundled, half slid into the crater. On the far side, the stripped track lay flat on the crater’s slope, a stride-wide strip of flat metal sections leading up like a ramshackle escalator almost to the hole’s jagged lip. In front of us, huge guide wheels protruded from the war machine’s hull; some supported the giant hinges of the tracks’ upper course, others ran on the tracks beneath. Quilan was trapped beneath their lower level, squashed into the mud with only his upper torso free.

Our comrades were dead. There were only Quilan and me, and the pilot of the light flyer, returning to pick us up. The ship, just a couple of hundred kilometres above our heads, could not help.

I had tried pulling Quilan, ignoring his bitten-off moans, but he was held fast. I had burned out my suit’s AG unit trying to shift the track sections trapping him, and cursed our supposedly wonderful nth generation projectile weapons; so good for killing our own species and penetrating armour, so useless for cutting through thick metal.

Noise crackled nearby; sparks flicked out of the fire in the turret aperture, rising and fading in the rain. I could feel the detonations through the ground, transmitted by the body of the wrecked machine.

“Ammunition, going off,” Quilan said, his voice strained. “Time you went.”

“No. I think whatever blew the turret off accounted for all the ammunition.”

“And I don’t. It could still blow up. Get out.”

“No. I’m comfortable here.”

“You’re what?”

“I’m comfortable here.”

“Now you’re being idiotic.”

“I am not being idiotic. Stop trying to get rid of me.”

“Why should I? You’re being idiotic.”

“Stop calling me idiotic, will you? You’re bickering.”

“I am not bickering. I’m trying to get you to behave rationally.”

“I am behaving rationally.”

“This doesn’t impress me, you know. It’s your duty to save yourself.”

“And yours not to despair.”

“Not despair? My comrade and mate is acting like an imbecile and I’ve got a—” Quilan’s eyes widened. “Up there!” he hissed, pointing behind me.

“What?” I twisted, bringing my rifle round and then going still.

The Invisible trooper was at the crater lip, peering down at the wreckage of the land destroyer. He had some sort of helmet on but it didn’t cover his eyes and probably wasn’t very sophisticated. I gazed up through the rain. He was lit by firelight from the burning land destroyer; we ought to be mostly in shadow. The trooper’s rifle was held in one hand, not both. I stayed very still.

Then he brought something up to his eyes, scanning. He stopped, looking straight at us. I had raised the rifle and fired by the time he’d let the night sight drop and begun to bring his weapon to bear. He exploded in light just as another flash erupted in the skies above. Most of his body tumbled and slipped down the slope towards us, shorn of one arm and his head.

“Suddenly you’re a half-decent shot,” Quilan said.

“I always was, dear,” I told him, patting his sho

ulder. “I just kept it quiet because I didn’t want to embarrass you.”

“Worosei,” he said, taking my hand again. “That one will not have been alone. Now really is the time to go.”

“I—” I began, then the hulk of the land destroyer and the crater around us shook as something exploded inside the wreck and glowing shrapnel whizzed out of the space where the turret had been. Quilan gasped with pain. Mud slides coasted down around us and the remains of the dead Invisible slid another few strides closer. His gun was still clutched in one armoured glove. I glanced at my helm’s screen again. The flyer was almost here. My love was right, and it really was time to go.

I turned back to say something to him.

“Just fetch me that bastard’s rifle,” he said, nodding at the dead trooper. “See if I can’t take another one or two of them with me.”

“All right,” I said, and found myself scrambling up the mud and debris and grabbing the dead soldier’s rifle.

“And see if he has anything else!” Quilan shouted. “Grenades; anything!”

I slid back down, overshooting and getting both boots in the water. “All he had,” I said, handing him the rifle.

He checked it as best he could. “That’ll do.” He fitted the stock against his shoulder and twisted round as far as his trapped lower body would allow, settling into something approaching a firing position. “Now, go! Before I shoot you myself!” He had to raise his voice over the sound of more explosions tearing at the wreck of the land destroyer.

I fell forward and kissed him. “I’ll see you in heaven,” I said.

His face took on a look of tenderness just for a moment and he said something, but explosions shook the ground and I had to ask him to repeat what he’d said as the echoes died away and more lights strobed in the skies above us. A signal blinked urgently in my visor to tell me the flyer was immediately overhead.

“I said, there’s no rush,” he told me quietly, and smiled. “Just live, Worosei. Live for me. For both of us. Promise.”

“I promise.”

He nodded up the slope of the crater. “Good luck, Worosei.”

I meant to say good luck in return, or just goodbye, but I found I could not say a thing. I just gazed hopelessly at him, looking upon my husband for that one last time, and then I turned and hauled myself upwards, slithering on the mud but pulling myself away from him, past the body of the Invisible I had killed, along the side of the burning machine’s hull and traversing its rear beneath the barrels of its aft turret while more explosions sent flaming wreckage soaring into the rain-filled sky and splashing into the rising waters.

The sides of the crater were slick with mud and oils; I seemed to slip down more than I was able to climb up and for a few moments I believed I would never make my way out of that awful pit, until I slid and hauled myself over to the broad metal ribbon that was the stripped track of the land destroyer. What would kill my love saved me; I used the linked sections of the embedded track as a staircase, at the end almost running to the top.

Beyond the lip, in the flame-lit distances between the ruined buildings and the squalls of rain, I could see the lumbering shapes of other great war machines, and the tiny, scurrying figures behind them, all moving this way.

The flyer swooped from the clouds; I threw myself aboard and we lifted immediately. I tried to turn and look back, but the doors slammed closed and I was thrown about the cramped interior while the tiny craft dodged rays and missiles aimed at it as it rose to the waiting ship Winter Storm.

The Light of Ancient Mistakes

The barges lay on the darkness of the still canal, their lines softened by the snow heaped in pillows and hummocks on their decks. The horizontal surfaces of the canal’s paths, piers, bollards and lifting bridges bore the same full billowed weight of snow, and the tall buildings set back from the quaysides loomed over all, their windows, balconies and gutters each a line edged with white.

It was a quiet area of the city at almost any time, Kabe knew, but tonight it both seemed and was quieter still. He could hear his own footsteps as they sank into the untouched whiteness. Each step made a creaking noise. He stopped and lifted his head, sniffing at the air. Very still. He had never known the city so silent. The snow made it seem hushed, he supposed, muffling what little sound there was. Also tonight there was no appreciable wind at ground level, which meant that—in the absence of any traffic—the canal, though still free of ice, was perfectly still and soundless, with no slap of wave or gurgling surge.

There were no lights nearby positioned to reflect from the canal’s black surface, so that it seemed like nothing, like an absolute absence on which the barges appeared to be floating unsupported. That was unusual too. The lights were out across the whole city, across almost all this side of the world.

He looked up. The snow was easing now. Spinwards, over the city centre and the still more distant mountains, the clouds were parting, revealing a few of the brighter stars as the weather system cleared. A thin, dimly glowing line directly above—coming and going as the clouds moved slowly overhead—was far-side light. No aircraft or ships that he could see. Even the birds of the air seemed to have stayed in their roosts.

And no music. Usually in Aquime City you could hear music coming from somewhere or other, if you listened hard enough (and he was good at listening hard). But this evening he couldn’t hear any.

Subdued. That was the word. The place was subdued. This was a special, rather sombre night (“Tonight you dance by the light of ancient mistakes!” Ziller had said in an interview that morning. With only a little too much relish) and the mood seemed to have infected all of the city, the whole of Xarawe Plate, indeed the entire Orbital of Masaq’.

And yet, even so, there seemed to be an extra stillness caused by the snow. Kabe stood for a moment longer, wondering exactly what might cause that additional hush. It was something that he had noticed before but never quite been bothered enough about to try and pin down. Something to do with the snow itself…

He looked back at his tracks in the snow covering the canal path. Three lines of footprints. He wondered what a human—what any bipedal—would make of such a trail. Probably, he suspected, they would not notice. Even if they did, they would just ask and instantly be told. Hub would tell them: those will be the tracks of our honoured Homomdan guest Ambassador Kabe Ischloear.

Ah, so little mystery, these days. Kabe looked around, then quickly did a little hopping, shuffling dance, executing the steps with a delicacy belying his bulk and weight. He glanced about again, and was glad to have, apparently, escaped observation. He studied the pattern his dance had left in the snow. That was better… But what had he been thinking of? The snow, and its silence.

Yes, that was it; it produced what seemed like a subtraction of noise, because one was used to sound accompanying weather; wind sighed or roared, rain drummed or hissed or—if it was mist and too light to produce noise directly—at least created drips and glugs. But snow falling with no wind to accompany it seemed to defy nature; it was like watching a screen with the sound off, it was like being deaf. That was it.

Satisfied, Kabe tramped on down the path, just as a whole sloped roof-load of snow fell with a muffled but distinct crump from a tall building onto ground nearby. He stopped, looked at the long ridge of whiteness the miniature avalanche had produced as a last few flakes fell swirling around it, and laughed.

Quietly, so as not to disturb the silence.

At last some lights, from a big barge four vessels away round the canal’s gradual curve. And the hint of some music, too, from the same source. Gentle, undemanding music, but music nevertheless. Fill-in music; biding music, as they sometimes called it. Not the recital itself.

A recital. Kabe wondered why he had been invited. The Contact drone E. H. Tersono had requested Kabe’s presence there in a message delivered that afternoon. It had been written in ink, on card and delivered by a small drone. Well, a flying salver, really. The thing was, Kabe usually went t

o Tersono’s Eighth-Day recital anyway. Making a point of inviting him to it had to mean something. Was he being told that he was being in some way presumptuous, having come along on earlier occasions when he hadn’t been specifically invited?

That would seem strange; in theory the event was open to all—what was not, in theory?—but the ways of Culture people, especially drones, and most especially old drones, like E. H. Tersono, could still surprise Kabe. No laws or written regulations at all, but so many little… observances, sets of manners, ways of behaving politely. And fashions. They had fashions in so many things, from the most trivial to the most momentous.

Trivial: that paper message delivered on a salver; did that mean that everybody was going to start physically moving invitations and even day-to-day information from place to place, rather than have such things transmitted normally, communicated to one’s house, familiar, drone, terminal or implant? What a preposterous and deeply tedious idea! And yet just the sort of retrospective affectation they might fall in love with, for a season or so (ha! At most).

Momentous: they lived or died by whim! A few of their more famous people announced they would live once and die forever, and billions did likewise; then a new trend would start amongst opinion-formers for people to back-up and have their bodies wholly renewed or new ones regrown, or to have their personalities transferred into android replicas or some other more bizarre design, or… well, anything; there was really no limit, but the point was that people would start doing that sort of thing by the billion, too, just because it had become fashionable.

Was that the sort of behaviour one ought to expect from a mature society? Mortality as a life-style choice? Kabe knew the answer his own people would give. It was madness, childishness, disrespectful of oneself and life itself; a kind of heresy. He, however, was not quite so sure, which either meant that he had been here too long, or that he was merely displaying the shockingly promiscuous empathy towards the Culture that had helped bring him here in the first place.