Resist

Hugh Howey

Table of Contents

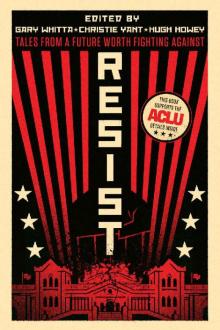

RESIST | Tales From A Future Worth Fighting Against

Copyright

About the ACLU

Foreword

America: The Ride | Charles Yu

The Defense of Free Mind | Desirina Boskovich

Aware | C. Robert Cargill

Black Like Them | Troy L. Wiggins

Monster Queens | Sarah Kuhn

Morel and Upwright | David Wellington

Don't Wait Up | Fran Wilde

Clay and Smokeless Fire | Saladin Ahmed

The Arc Bends | Kieron Gillen

The Blast | Hugh Howey

Excerpts from the Records | Chet Williamson

Horatius and Clodia | Charlie Jane Anders

The Nothing Men | Jason Arnopp

Catcall | Delilah S. Dawson

Mona Lisa Smile | Beth Revis

The Waters | Kevin Hearne

Five Lessons in the Fattening Room | Khaalidah Muhammad-Ali

The Tale of the Wicked | John Scalzi

The Processing | Leigh Alexander

The Well | Laura Hudson

Bastion | Daniel H. Wilson

What Someone Else Does Not Want Printed | Elizabeth Bear

Three Points Masculine | An Owomoyela

Where The Women Go | Madeleine Roux

Three Speeches About Billy Grainger | Jake Kerr

The Venus Effect | Violet Allen

About the Authors

Acknowledgements

About the Editors

Publication Credits

Resist: Tales From a Future Worth Fighting Against © 2018

by Gary Whitta, Hugh Howey, and Christie Yant

Cover design by M.S. Corley

Interior layout and design by Matt Bright | www.inkspiraldesign.co.uk

Proofread by Jane Davis | www.thehelpfultranslator.com

All rights reserved

Introduction © 2018 by Gary Whitta, Hugh Howey, and Christie Yant

An extension of this copyright page can be found here.

ABOUT THE ACLU

THANK YOU FOR buying this book. By doing so you’re helping to support an important cause. A minimum of 50% of the purchase price will be donated to the American Civil Liberties Union.

For nearly 100 years, the ACLU has been our nation’s guardian of liberty, working in courts, legislatures, and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties that the Constitution and the laws of the United States guarantee everyone in this country.

Whether it’s achieving full equality for LGBT people, establishing new privacy protections for our digital age of widespread government surveillance, ending mass incarceration, or preserving the right to vote or the right to have an abortion, the ACLU takes up the toughest civil liberties cases and issues to defend all people from government abuse and overreach.

With more than 2 million members, activists, and supporters, the ACLU is a nationwide organization that fights tirelessly in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and Washington, D.C., to safeguard everyone’s rights.

FOREWORD

THE FUTURE IS unknown, which is both exciting and terrifying. It is a place for dreamers and worriers to project their hopes and fears. Science fiction as a literary genre has a long history of filling readers’ minds with wondrous possibilities but also dire predictions. Utopias and dystopias. Flying cars and murderous robots.

And while every generation makes the mistake of thinking their time is special, there is some truth in this egoistic view—for all times are special in equal amounts. The recent past is always worth exploring, the present is always full of miraculous advancements, and the future always holds both promise and danger. This is most evident when it feels as if the past is repeating itself.

This anthology has been collected in just such times. There are echoes today of the same nationalism, protectionism, and xenophobia that led to last century’s world wars. Icons of heinous civil wars are being torn down, and those same acts are being protested by those who think our ugliest times were our best times. There are world leaders today whose rhetoric reminds us of speeches we thought we would never tolerate again.

It’s common enough to wonder how we might have responded had we lived in different times. Would we stand up for the rights of others and risk our privilege? Would we be brave enough to speak truth to power if we were in an unprotected minority? It’s easy to be brave after the fact; how would we respond in the moment?

This feels like one of those moments. But the truth is that if you look hard enough, these moments never go away. There is always something good worth fighting for and something bad worth resisting. The unknown future is created by the choices we make today. The warnings and promise of George Orwell’s 1984 and Arthur C. Clark’s 2001: A Space Odyssey get everything right except the dates. Margaret Atwood was clever to avoid that mistake, and there’s a reason her Handmaid’s Tale is back with a vengeance. These stories should never date themselves. We should always be wary of and joyful for the future in equal measure.

The undeniable and unbelievable truth is that the future is always better than the past. We do make progress. But the world only gets better because we fight for it. We fight by voting, marching, volunteering, donating, parenting, mentoring, and yes sometimes even Tweeting. And for some of us, the thing we do best is to write entertaining warnings, to draw readers in with stories and characters that capture the imagination while liberating the spirit. That’s what we, the editors, hope to accomplish with this anthology. It comes from a wide variety of voices, but they sing in chorus. They sing about a future that might be dire, but that we believe we are collectively amazing enough to avoid. It is a future that entertains, but is worth fighting against. We hope you enjoy. And we hope to see you all soon in a very different future.

Gary Whitta, Christie Yant, and Hugh Howey

AMERICA: THE RIDE

CHARLES YU

WE HAVE A kid now and another on the way and—the idea is, the hope is—that we are, at least in a technical sense, adults.

We’d always assumed we would know more, would have accomplished more, by the time we got to this point, assumed we would have turned into different people, better people. That was the idea. That was the hope.

Looking back over our shoulders, we can see the track stretching out behind us, an unbroken line from where we got on to where we are now.

The voice of the American ride says:

Please keep your attention focused in a sideways direction.

Reminding us the proper way to enjoy this, which is not to look back, because looking back is the easiest way to get hurt. Or, worse, to convince yourself that you want to get off. And also, it’s also not proper procedure to look forward, no matter how tempting it is to do so. We sit facing west while our tram car moves north, and we do our best not to look in the northern direction, although we are encouraged by what we feel to be a subtle, gentle, but unmistakable angle of incline of the track below us. We are moving up a slope, building toward something, to a higher place. Some of us worry about what this means. Some of us worry about whether an upslope now implies a downslope later, but some others of us say that it doesn’t have to be so, that we are not bodies in flight, our arc through the sky pre-carved by gravity. We are on an engineered system, an amusement, a transportation. This was designed by our best minds, assembled by our best hands, and constantly improved by our innovation and creativity. There is no reason to assume that there must be a high point to all this, that we will eventually have to convert all

of this elevation and potential energy into speed and kinetic energy, that what we are storing thermodynamically must eventually be given back, paid back like an entropic or economic debt.

The voice reminds us again to keep our hands and feet inside at all times and to maybe take our eyes off our phones for like, one second, and gaze outward as we make our way along the tracks. Not to turn around in our seats and look backward in the direction of history, at the past which is already gone, but to always look forward, at the grandeur of the vistas, the sweep of world events unfolding, which we are a part of, which is what we paid for, four hundred dollars a ticket, half-price for children (although as they grow, they will eventually turn into full-fare passengers on this ride, and we worry about the mechanics of how that incremental fare will be collected, whether we will be able to pay for them or if they will need to pay for it themselves, who will come for it, and whether we will still be around, whether we will have any warning, whether we will still be able to stay in this car with them or whether they will need to get out and ride in their own vehicles, we worry whether the track might diverge at some point and they will be off into a different set of tunnels and rooms and we will never see them again).

The sweep of history, having this unspoken feeling of forward and upward momentum, while being entertained, all of that goes into the ticket price, and the voice of the woman who narrates the ride, she reminds us that it is our purchase of these tickets that makes the ride possible. We are the customers, but we are also the underwriters of this entertainment. We are consumers of this experience. We are tourists in our own creation.

“We’re moving,” our daughter says, clapping her hands in excitement. “Let’s go! Where are we going?”

She is not a baby anymore. Our wife starts to cry.

“How did that happen?” our wife says. She starts to turn her head back, hoping she might still be able to see the point in the track where our baby turned into a kid who could say things to us, but we stop our wife from looking back, reminding her that the voice will be angry.

Our car moves down the track. We are picking up speed. We are approaching a house. Our daughter asks us if that is our house and we say we aren’t sure, but something tells us that it is. We are headed for a collision, but then a set of double doors opens and we find ourselves inside the living room of our house.

“This feels like home,” we say to each other, but we also hear other people around us saying it and for the first time in a long time we are aware that we are not on this ride alone. In fact, there are other families in the neighboring cars just ahead of us and just behind us, sitting so close we could reach out and touch them. We look ahead and see that it is all families, all the way down, this tram being an endless procession of small car units, all of us connected by the central drive-train powering this ride, subdivided but linked, having our own versions of the same experience. There is a lot of murmuring now as we hear a lot of us saying “Is this home?” “Where are we?” and we start to wonder what we are, exactly, whether up to this point our definition of “we” has been too small. We wonder who we are. But just as we are starting to wonder about how large “we” are as a group, the nature of “we” and the mystery and the wonder and the pluses and the minuses of it, we hear someone say “I don’t know about this.” We have an “I” among us and everyone turns to see if they can figure out who it is, but just as that happens, the tram uncouples from itself and breaks into two, and one part of us goes off on one track and the other part goes off on a different track, and the uncoupling happens again and again and again until we find ourselves alone, together, alone. Together as a small family unit, but now uncoupled from our fellow riders. Alone now, moving in our single transport vehicle, on our own ride, wondering what we are missing out on, what other riders are getting to see.

Now we wish we had paid more attention at the beginning of the ride, had not been listening to the voice to keep looking sideways, at the murals and the dioramas and displays of the ride’s retail partners. But it was hard not to do so. They make it so easy, we did not even have to move, just take out our credit cards and hold them near the edge of our car in such a way that they could be swiped through the many point-of-sale devices installed every fifty feet along the ride, millions, billions of transactions occurring every instant, so that we could instantly own a part of this experience, if we wanted to, to have souvenirs of all types, cultural, historical, key chains and cups with crazy straws. It was part of our duty as riders to help support the sponsors that make the ride possible, and it allowed us to participate, each according to our means and personalities, allowed us to choose how we wanted to enjoy this, all of this. We pass through the house, seeing our living room, our three bedrooms and two and a half bathrooms, our kitchen, and we exit back out into the light and what we see is a thousand different tracks, or a million, or four hundred million.

“The ride is broken,” our son says.

“Hey!” we say. “We have a son?” and we kiss him and squeeze his cheeks and he pushes our hands away.

“I’m not a baby,” he says.

“You’re not,” we say, because he’s not, but we wonder. “When? How? Where were you born?”

“Back there,” our son says, “in the house. You guys seemed really freaked out about something and I didn’t want to bother you so I’ve been quiet for a while,” and he doesn’t seem too hurt, already so grown-up and used to being the younger kid, and although we feel like we just met him a moment ago, he has been with us for some time now and we already love him. He is ten, our son, and we look at his hair and his nose and his shoulders and we admire him. Our daughter, now thirteen, seems to have known he was here all along and is waiting for us to catch up.

“What are you looking at?” we ask our new son.

“Cars.”

“They’re nicer than ours,” we say. “Our car is old, huh?”

“Yeah,” he says. “But I like our car. It’s the best one.”

All of the cars move along their individual paths, some up into the mountains, some turn into boats and float onto lakes, some take off like airplanes as we watch in envy, some hit trees and we watch the families inside get out and start fighting and we wonder if they will ever be able to get back on. Our car continues smoothly along its track, not the fastest, nor the slowest.

We notice now that the ride is not what it used to be, less finished, more construction. We see a sign posting notice that the ride is now owned by American Enterprises, LLC, whose parent company, American Entertainments, Inc. is a subsidiary itself of a company called The USAmusement Corporation, which is owned by a German conglomerate, New World Experiments GmbH, owned by a consortium led by Chinese and Korean investors.

You have been chosen as potential partners in an affiliate marketing and peer-advertising campaign …

the voice says, as we continue to roll on through history.

You’re now passing through: Japanese internment camps during the Second World War.

On your left, coming up, you will see Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York in the 1920s.

And if you look over to your right, you’ll see the banks of the Mississippi, and, watch your feet, lift them up to stay dry, as your vehicle is now converting itself into a riverboat, a form of transportation vital to the nation’s commerce throughout the 19th century. No mention of other parts of the U.S. economy in that century.

Backward we go, through American lore and mythology, merchandised to perfection.

We see new ground being broken, dig sites surrounded by chain-link fences, men working in hardhats, large colorful banners proclaiming that The American Experience will be re-launched in the fall of 3015.

This is a part of the ride that seems like we are not on a ride anymore.

We have crossed some line into the backstage area, employees only, where the gears and the machine room and the electrical cords and all of the nuts and bolts of the mechanical ride are evident. Even the voice has dropped some o

f the theatre from her voice and now talks to us directly.

“The narrated portion of the ride is over. You are now entering an experimental phase, still in testing, for a 3-D version of America, where riders can experience “America” for the first time, in 3-D.”

Our son and our daughter both get excited at the idea for a moment until the voice tells us that we do not qualify financially for that portion of the ride.

“You are welcome to stay in the car, although what you will see will be a flattened, 2-D version of what should be a stereoscopic experience.”

We are given a choice of whether to go on or get out, and we decide to go on, although the voice now also tells us that we need to take some of the things out of the car, as we have taken on too much weight, so our son drops his sack lunch over the side of the car, and we drop a typewriter, and old clothes that the kids used to wear, and our daughter drops a doll whose hair she used to brush when she was a little girl at the beginning of the ride.

We are just content to keep riding this for a while, passing through a room they called Your 30s, which has upbeat, contemplative acoustic guitar music, and Your 40s which is more piano-themed, and Your 50s which has Bach playing and we see some cars getting wine and cheese. We see cars that have God with them, in voice and as a kind of hologram, and we watch God from afar, and wish we could hear what God is saying to the people in the cars lucky enough to have God, but the advertising voices all around our car are drowning everything out. We pass through dioramas of ourselves in cubicles, watching time-lapse movies of ourselves working, working, aging, seeing what we look like at work, seeing how the hands of the clocks in our offices spin around, and somewhere around that point we notice that our lap bars have tightened over our thighs. It could be the slow spread of middle age, and the growth of our daughter, who is in college now, and our son who as a sophomore made the varsity soccer team at his high school and is now taller than all of us.