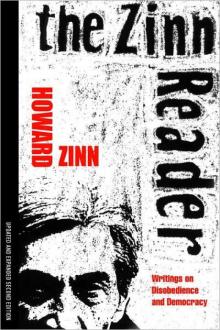

The Zinn Reader: Writings on Disobedience and Democracy

Howard Zinn

To Noah, and his generation.

Acknowledgments

I must first thank my editor and publisher, Dan Simon of Seven Stories Press, not just for initiating this project, but for carrying it through all the way with extraordinary intelligence and energy. He is an ideal editor, clear in his vision of what a book should be, firm in pursuing that vision, and still sensitive to the needs of the writer—altogether a pleasure to work with.

My wife Roslyn, as always, encouraged me to do what had to be done, providing wise counsel again and again.

Thanks also to HarperCollins for permission to use material from my book Declarations of Independence, to Beacon Press for permission to use material from my book You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train, to the University of Illinois Press for permission to use material from my book The Politics of History.

Introduction

This seems to me a big book to swallow, and I blame it on the fact that in 1978, when I was teaching in Paris, I looked up the son of friends back in the States, a young man of college age. He was working in a tiny restaurant in the Latin Quarter—indeed with only one table—Le Petit Vatel. This was the start of a friendship with Dan Simon, who went on to become the ingenious editor and publisher of the small, independent, much-respected Seven Stories Press, and who proposed the idea of a Zinn Reader.

I delayed my response for two years, to give the appearance of modesty, and then agreed. I wanted to think of it as a generous act—giving all those who know my biggest-selling book (A People's History of the United States) a chance to sample my other work: books out of print, books still in print, essays, articles, pamphlets, lectures, reviews, newspaper columns, written over the past thirty-five years or so, and often not easy to find. An opportunity, or a punishment? Only the reader can decide.

My first published writings came out of my seven years in the South, teaching at Spelman College, a college for black women in Atlanta, Georgia. I was finishing my Ph.D. in history at Columbia University, with the indispensable help of the GI Bill, after serving as a bombardier with the Eighth Air Force in World War II.

My years at Spelman were 1956 to 1963, and I became involved, with my students, in the Southern movement against racial segregation. My very first published article, in Harper's Magazine in 1959 ("A Fate Worse Than Integration"), became the basis for a larger essay "The Southern Mystique," which appeared in The American Scholar.

I was invited to become a member of the executive board (as an "adult adviser") of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which had come out of the sit-ins and was, I think it is fair to say, the leading edge of the Southern civil rights movement. In the next several years I became an observer-participant in demonstrations in Atlanta; in Albany, Georgia; Selma, Alabama; and Hattiesburg, Mississippi. I was now writing for The Nation, The New Republic, The Crisis, and other publications.

The historian Martin Duberman, whose documentary play, In White America, I had greatly admired, asked me to write an essay comparing the Civil War-era abolitionists with the activists of the Sixties. It appeared in a volume he edited called The Anti-Slavery Vanguard, and I called it "Abolitionists, Freedom Riders, and the Tactics of Agitation." It was an approach I was going to use again and again—to find wisdom and inspiration from the past for movements seeking social justice in our time.

There was never, for me as teacher and writer, an obsession with "objectivity," which I considered neither possible nor desirable. I understood early that what is presented as "history" or as "news" is inevitably a selection out of an infinite amount of information, and that what is selected depends on what the selector thinks is important.

Those who talk from high perches about the sanctity of "facts" are parroting Charles Dickens' stiff-backed pedant in Hard Times, Mr. Gradgrind, who insisted his students give him "facts, facts, nothing but facts." But behind any presented fact, I had come to believe, is a judgment— the judgment that this fact is important to put forward (and, by implication, other facts may be ignored). And any such judgment reflects the beliefs, the values of the historian, however he or she pretends to "objectivity."

I was relieved when I decided that keeping one's judgments out of historical narrative was impossible, because I had already determined that I would never do that. I had grown up amidst poverty, had been in a war, had witnessed the ugliness of race hatred, and I was not going to pretend to neutrality.

As I told my students at the start of my courses, "You can't be neutral on a moving train." That is, the world is already moving in certain directions—many of them horrifying. Children are going hungry, people are dying in wars. To be neutral in such a situation is to collaborate with what is going on. The word "collaborator" had a deadly meaning in the Nazi era. It should have that meaning still.

Therefore, I doubt you will find in the following pages any hint of "neutrality."

The GI Bill paid my way all through undergraduate and graduate school. While my wife, Roslyn, worked, and our two kids were in nursery school, we lived in a low-income housing project on the Lower East Side. I attended classes during the day and worked the four to midnight shift loading trucks at a Manhattan warehouse. It is hardly surprising that I was to have a persistent interest, as a historian, in the issue of economic justice.

For my doctoral thesis at Columbia University I chose as my subject Fiorello LaGuardia. He was known best as the feisty, rambunctious mayor of New York in the New Deal era, but before that, in the Twenties, he was in Congress, representing a district of poor people in East Harlem.

As I began reading through his papers, left to the Municipal Archives in New York by his widow, he spoke to my young radicalism. He was on his feet in the House of Representatives perhaps more often than any other member, demanding to be heard above the din of the Jazz Age, crying out to the nation about the reality of suffering underneath the spurious "prosperity" of the Twenties.

My thesis, "Conscience of the Jazz Age: LaGuardia in Congress," won a prize from the American Historical Association, which sponsored its publication by Cornell University Press. Out of that came an essay published in my book The Politics of History. It was a glimpse of LaGuardia at work against the hypocrisy of "a booming economy" which concealed distress. We see that today in the exultation accompanying every upward leap in the Dow Jones average, even while a quarter of the nation's children grow up in poverty.

Reading on my own, I became fascinated by the history of labor struggles in the United States, something that was absent in my courses in American history. Reaching back into that history (often disheartening, often inspiring), I began to look closely into the Colorado coal strike of 1913-14, and my essay "The Ludlow Massacre" comes out of that.

Later, when I was asked to edit a volume of writings on New Deal Thought, I found even the welcome reforms of the New Deal insufficient. My introduction to that volume, printed here as "The Limits of the New Deal," points to the inability of the Roosevelt reforms to cure the underlying sickness of a system which put business profit ahead of human need. There were thinkers in the Thirties who understood this, and I used the volume to present their ideas.

In 1963, Roz, our children, and I left Spelman College and Atlanta and headed to Boston. Although I was a full professor, with tenure, and head of the department at Spelman, I had been fired for "insubordination." I suppose the charge was accurate; I had supported the Spelman students in their revolt against a tyrannical and patronizing administration.

I continued to go back and forth to the South, participating (with Roz) in the Mississipi Freedom Summer of 1964, joining the Selma to Montgomery march, and wr

iting about my experiences. That year in Boston I wrote two books about the South and the Movement: SNCC: The New Abolitionists (Beacon Press) and The Southern Mystique (Alfred Knopf).

An invitation came to join the department of political science at Boston University just about the time the United States was intensifying its military intervention in Vietnam. I became active in the movement against the war and began writing about it with the same sense of urgency that surrounded my writing on events in the South.

I reprint here some material from my book Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal, published in early 1967 by Beacon Press. There had been a number of books published on the war, but mine was the first, I believe, to call for an immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam. Its final chapter, which I include in this volume, is a speech I wrote "for Lyndon Johnson" (no, he didn't ask for it) in which I have him announcing such a withdrawal and explaining his reasons to the nation. This speech was reproduced in a number of newspapers around the country.

Even before American intervention in Vietnam, the problem of war was a central preoccuption for me. I had been a bombardier, an enthusiastic one, in the "good war," the war against Fascism, and yet, when the war was over, I began to rethink the question of whether there was such a thing as a good war, a just war. I explore that in the opening essay of the section on War in this reader.

I did a good deal of research on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki while I was a Fellow in East Asian Studies at Harvard University in 1961, and wrote an article for the Columbia University Forum called "A Mess of Death and Documents." Later, I made a connection between the bombing of Hiroshima and a much smaller event of World War II, but one in which I had been a participant, the bizarre and deadly napalm bombing of the French town of Royan just before the war's end. In 1967, I visited the town which I had bombed, pored through its records, and wrote an essay which then appeared in my book The Politics of History, and which I reproduce here.

In the tumultuous years of the movement against the Vietnam War, the issue of civil disobedience, the role of law in society and its relation to justice, became for me important philosophical problems, as well as practical ones. (I was arrested myself a number of times for protesting the war.)

You will find reprinted here some of my writings on those issues, as well as descriptions of my experience as witness in the Pentagon Papers case and other trials of war protesters. In one essay, I examine critically the views of Plato on obligation to the state. This appeared as an essay in Z Magazine (a friendly venue for radical writers) and was reproduced in my book Failure to Quit.

In 1974, with the Vietnam war coming to a close, I was invited by the Boston Globe (along with a militant student activist named Eric Mann) to write a bi-weekly column. We did that for over a year, until our columns became a little hard to take. The liberalism of the Globe had its limits. I wrote an anti-war, anti-militarism column for Memorial Day, 1976 (reprinted here), and after it appeared I was informed that my column was no longer wanted.

I was by profession a historian, by choice an activist, and the tension between the two was something I thought about constantly. What was the proper (or improper) role of the historian in a time of crisis. That was the subject of my book The Politics of History (first published by Beacon Press in 1970, reissued later by the University of Illinois Press). I reprint here several essays illustrating my approach to history, as in the talk I gave at the University of Wisconsin during the 1992 quincentennial discussions of Columbus.

And what should be the function of a university when the world outside is in turmoil? At Boston University, faculty and students found themselves debating such questions, and I was very much in the midst of that. Once more, I was being "insubordinate" in my relations with the university administration, and several of the essays in this volume reflect that. One of these "A University Should Not Be A Democracy" (a quote from my university president) appeared in The Progressive.

Throughout my activity and my writings, questions arose, both practical and theoretical, of how injustice can be remedied. How does social change come about, and what tactics are both effective and morally acceptable in that process? And what reason do we have to be hopeful? The final set of essays, dealing with such issues, are drawn from The Nation, Z Magazine, The Boston Globe, from other periodicals, and from my memoir You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train.

I have certainly not been neutral. I have tried to keep moving. I hope a few readers will come along with me.

—Auburndale, MA

July 1997

PART ONE

RACE

1

The Southern Mystique

I did not deliberately seek employment in a black college. I was only vaguely aware that such an institution existed when, in 1956, about to get my doctorate at Columbia University, I was introduced to the president of Spelman College, a college for African-American women in Atlanta, Georgia. He offered me a tempting job—chair of Spelman's department of history and social science. My wife and I, with our young son and daughter, spent the next seven years living in Atlanta's black community, certainly the most interesting seven years of my life. I soon became involved, along with my students, in what came to be known affectionately as "the movement." I did not see how I could teach about liberty and democracy in the classroom and remain silent about their absence outside the classroom. I became both participant in and chronicler of the growing conflict between the old Southern order of racial segregation, and the increasingly vocal demands for freedom and equality by Southern blacks. Some long-held notions about the South, white people and black people, were powerfully challenged by what I observed. I sent an article to Harper's Magazine, and to my surprise they accepted it.

It was my first published article, and later became the basis for an essay I wrote for The American Scholar in the winter issue, 1963-64, and as the introductory chapter in my book The Southern Mystique (Alfred Knopf, 1964).

Do I stand by everything I wrote thirty years ago about the race question in the United States? That would mean I have learned nothing from all these years of turmoil. I undoubtedly would not write exactly the same way today. But I suppose I believe in the long-run validity of what I say in this essay, and so I unashamedly reproduce it here.

It has occurred to me only recently that perhaps the most striking development in the South is not that the process of desegregation is under way, but that the mystique with which Americans have always surrounded the South is beginning to vanish.

Driving into Atlanta in a heavy rain one hot August night six and a half years ago, my wife and two small children waking up to watch the shimmering wet lights on Ponce de Leon Avenue, I was as immersed in this mystique as anyone else. For the last full day of driving, the talk and the look of people were different. The trees and fields seemed different. The air itself smelled different. This was the mysterious and terrible South, the Deep South, soaked in blood and history, of which Faulkner wrote—and Margaret Mitchell, and Wilbur J. Cash. White Atlanta had been ravaged and still knew it. Negroes had been slaves and still remembered it. Northerners were strangers, no matter how long they stayed, and would never forget it.

There was something about Atlanta, about Georgia, the Carolinas, that marked them off as with a giant cleaver from the rest of the nation: the sun was hotter, the soil was redder, the people blacker and whiter, the air sweeter, heavier. But beyond the physical, beyond the strange look and smell of this country, was something more that went back to cotton and slavery, stretching into history as far as anyone could remember—an invisible mist over the entire Deep South, distorting justice, blurring perspective, and, most of all, indissoluble by reason.

It is six and a half years later, I have lived these years inside what is often thought to be the womb of the South's mystery: the Negro community of the Deep South. My time has been spent mostly with the remarkable young women in my classes at Spelman; but also with the earnest young men across the street at Morehouse,

with the strangely mixed faculties of the Negro colleges (the white and the dark, the silent and the angry, the conservative and the radical), with the black bourgeoisie of college presidents and business executives, with the poor Negro families in frame houses across the street and their children playing with ours on the campus grass. From this, I have been able to wander out into the glare of the white South, or cross into those tiny circles of shadow, out of sight, where people of several colors meet and touch as human beings, inside the tranquil eye of the hurricane.

The Southern mystique hovered nearby even on yellow spring afternoons when we talked quietly to one another in the classroom. At times it grew suddenly dense, fierce, asphyxiating. My students and I were ordered out of the gallery of the Georgia General Assembly, the Speaker of the House shouting hoarsely at us. One nightmarish winter evening, I was arrested and put behind bars. Hundreds of us marched one day toward the State Capitol where helmeted soldiers with rifles and gas masks waited. A dozen of us "sat in" at a department store cafeteria, silent as the manager dimmed the lights, closed the counter and ordered chairs piled on top of tables all around. I drove four hours south to the Black Belt country of Albany, Georgia, to call through a barbed wire fence surrounding the County Jail to a student of mine who was invisible beyond a wire mesh window. It was in Albany also that I sat in the office of the Sheriff of Dougherty County who a month before had given a bloody beating with a cane to a young Negro lawyer. And nowhere was the mystique so real, so enveloping, as on a dirt road in the dusk, deep in the cotton and peanut land of Lee County, Georgia, where justice and reason had never been, and where the night before bullets had ripped into a farm house belonging to Negro farmer James Mays and exploded around the heads of sleeping children.