Housing Problem

Henry Kuttner

Housing Problem

Henry Kuttner

HOUSING PROBLEM

Henry Kuttner

Jacqueline said it was a canary, but I contended that there were a couple of lovebirds in the covered cage. One canary could never make that much fuss. Besides, I liked to think of crusty old Mr. Henchard keeping lovebirds; it was so completely inappropriate. But whatever our roomer kept in that cage by his window, he shielded it—or them—jealously from prying eyes. All we had to go by were the noises.

And they weren’t too simple to figure out. From under the cretonne cloth came shufflings, rustlings, occasional faint and inexplicable pops, and once or twice a tiny thump that made the whole hidden cage shake on its redwood pedestal-stand. Mr. Henchard must have known that we were curious. But all he said when Jackie remarked that birds were nice to have around, was “Claptrap! Leave that cage alone, d’ya hear?”

That made us a little mad. We’re not snoopers, and after that brush-off, we coldly refused to even look at the shrouded cretonne shape. We didn’t want to lose Mr. Henchard, either. Roomers were surprisingly hard to get. Our little house was on the coast highway; ‘the town was a couple of dozen homes, a grocery, a liquor store, the post office and Terry’s restaurant. That was about all. Every morning Jackie and I hopped the bus and rode in to the factory, an hour away. By the time we got home, we were pretty tired. We couldn’t get any household help—war jobs paid a lot better—so we both pitched in and cleaned. As for cooking, we were Terry’s best customers.

The wages were good, but before the war we’d run up too many debts, so we needed extra dough. And that’s why we rented a room to Mr. Henchard. Off the beaten track with transportation difficult, and with the coast dimout every night, it wasn’t too easy to get a roomer. Mr. Henchard looked like a natural. He was, we figured, too old to get into mischief.

One day he wandered in, paid a deposit; presently he showed up with a huge Gladstone and a square canvas grip with leather handles. He was a creaking little old man with a bristling tonsure of stiff hair and a face like Popeye’s father, only more human. He wasn’t sour; he was just crusty. I had a feeling he’d spent most of his life in furnished rooms, minding his own business and puffing innumerable cigarettes through a long black holder. But he wasn’t one of those lonely old men you could safely feel sorry for—far from it! He wasn’t poor and he was completely self-sufficient. We loved him. I called him grandpa once, in an outburst of affection, and my skin blistered at the resultant remarks.

Some people are born under lucky stars. Mr. Henchard was like that. He was always finding money in the street. The few times we shot craps or played poker, he made passes and held straights without even trying. No question of sharp dealing—he was just lucky.

I remember the time we were all going down the long wooden stair way that leads from the cliff-top to the beach. Mr. Henchard kicked at a pretty big rock that was on one of the steps. The stone bounced down a little way, and then went right through one of the treads. The wood was completely rotten. We felt fairly certain that if Mr. Hen-chard, who was leading, had stepped on that rotten section, the whole thing would have collapsed.

And then there was the time I was riding up with him in the bus. The motor stopped a few minutes after we’d boarded the bus; the driver pulled over. A car was coming toward us along the highway and, as we stopped, one of its front tires blew out. It skidded into the ditch. If we hadn’t stopped when we did, there would have been a head-on collision. Not a soul was hurt.

Mr. Henchard wasn’t lonely; he went out by day, I think, and at night he sat in his room near the window most of the time. We knocked, of course, before coming in to clean, and sometimes he’d say, “Wait a minute.” There’d be a hasty rustling and the sound of that cretonne cover going on his bird cage. We wondered what sort of bird he had, and theorized on the possibility of a phoenix. The creature never sang. It made noises. Soft, odd, not-always-birdlike noises. By the time we got home from work, Mr. Henchard was always in his room. He stayed there while we cleaned. On week-ends, he never went out.

As for the cage .

One night Mr. Henchard came out, stuffing a cigarette into his holder, and looked us over.

“Mph,” said Mr. Henchard. “Listen, I’ve got some property to ‘tend to up north, and I’ll be away for a week or so. I’ll still pay the rent.”

“Oh, well,” Jackie said. “We can—”

“Claptrap,” he growled. “It’s my room. I’ll keep it if I like. How about that, hey?”

We agreed, and he smoked half his cigarette in one gasp. “Mm-mm. Well, look here, now. Always before I’ve had my own car. So I’ve taken my bird cage with me. This time I’ve got to travel on the bus, so I can’t take it. You’ve been pretty nice—not peepers or pryers. You got sense. I’m going to leave my bird cage here, but don’t you touch that cover!”

“The canary—” Jackie gulped. “It’ll starve.”

“Canary, hmm?” Mr. Henchard said, fixing her with a beady, wicked eye. “Never you mind. I left plenty o’ food and water. You just keep your hands off. Clean my room when it needs it, if you want, but don’t you dare touch the bird cage. What do you say?”

“Okay with us,” I said.

‘Well, you mind what I say,” he snapped.

That next night, when we got home, Mr. Henchard was gone. We went into his room and there was a note pinned to the cretonne cover. It said, “Mind, now!” Inside the cage something went rustle-whirr. And then there was a faint pop.

“Hell with it,” I said. “Want the shower first?”

“Yes,” Jackie said.

Whirr-r went the cage. But it wasn’t wings. Thump!

The next night I said, “Maybe he left enough food, but I bet the water’s getting low.”

“Eddie!” Jackie remarked.

“All right, I’m curious. But I don’t like the idea of birds dying of thirst, either.”

“Mr. Henchard said—”

“All right, again. Let’s go down to Terry’s and see what the lamb chop situation is.”

The next night—Oh, well. We lifted the cretonne. I still think we were less curious than worried. Jackie said she once knew somebody who used to beat his canary.

“We’ll find the poor beast cowering in chains,” she remarked flicking her dust-cloth at the windowsill, behind the cage. I turned off the vacuum. Whish—trot-trot-trot went something under the cretonne.

“Yeah—” I said. “Listen, Jackie. Mr. Henchard’s all right, but he’s a crackpot. That bird or birds may be thirsty now. I’m going to take a look.”

“No. Uh—yes. We both will, Eddie. We’ll split the responsibility.” I reached for the cover, and Jackie ducked under my arm and put her hand over mine.

Then we lifted a corner of the cloth. Something had been rustling around inside, but the instant we touched the cretonne, the sound stopped. I meant to take only one swift glance. My hand continued to lift the cover, though. I could see my arm moving and I couldn’t stop it. I was too busy looking.

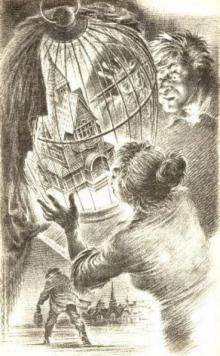

Inside the cage was a—well, a little house. It seemed complete in every detail. A tiny house painted white, with green shutters— ornamental, not meant to close—for the cottage was strictly modern. It was the sort of comfortable, well-built house you see all the time in the suburbs. The tiny windows had chintz curtains; they were lighted up, on the ground floor. The moment we lifted the cloth, each window suddenly blacked out. The lights didn’t go off, but shades snapped down with an irritated jerk. It happened fast. Neither of us saw who or what pulled down those shades.

I let go of the cover and stepped back, pulling Jackie with me.

“A d-doll house, Eddie!”

“With dolls in it?”

I stared past

her at the hooded cage. “Could you, maybe, do you think, perhaps, train a canary to pull down shades?”

“Oh, my! Eddie, listen.”

Faint sounds were coming from the cage. Rustles, and an almost inaudible pop. Then a scraping.

I went over and took the cretonne cloth clear off. This time I was ready; I watched the windows. But the shades flicked down as I blinked.

Jackie touched my arm and pointed. On the sloping roof was a miniature brick chimney; a wisp of pale smoke was rising from it. The smoke kept coming up, but it was so thin I couldn’t smell it.

“The c-canaries are c-cooking,” Jackie gurgled.

We stood there for a while, expecting almost anything. If a little green man had popped out of the front door and offered us three wishes, we shouldn’t have been much surprised. Only nothing happened.

There wasn’t a sound, now, from the wee house in the bird cage.

And the blinds were down. I could see that the whole affair was a masterpiece of detail. The little front porch had a tiny mat on it. There was a doorbell, too.

Most cages have removable bottoms. This one didn’t. Resin stains and dull gray metal showed where soldering had been done. The door was soldered shut, too. I could put my forefinger between the bars, but my thumb was too thick.

“It’s a nice little cottage, isn’t it?” Jackie said, her voice quavering. “They must be such little guys—”

“Guys?”

“Birds. Eddie, who lives in that house?”

‘Well,” I said. I took out my automatic pencil, gently inserted it be tween the bars of the cage, and poked at an open window, where the shade snapped up. From within the house something like the needle-

beam of a miniature flashlight shot into my eye, blinding me with its brilliance. As I grunted and jerked back, I heard a window slam and the shade come down again.

“Did you see what happened?”

“No, your head was in the way. But—”

As we looked, the lights went out. Only the thin smoke curling from the chimney indicated that anything was going on.

“Mr. Henchard’s a mad scientist,” Jackie muttered. “He shrinks people.”

“Not without an atom-smasher,” I said. “Every mad scientist’s got to have an atom-smasher to make artificial lightning.”

I put my pencil between the bars again. I aimed carefully, pressed the point against the doorbell, and rang. A thin shrilling was heard.

The shade at one of the windows by the door was twitched ‘aside hastily, and something probably looked at me. I don’t know. I wasn’t quick enough to see it. The shade fell back in place, and there was no more movement. I rang the bell till I got tired of it. Then I stopped.

“I could take the cage apart,” I said.

“Oh no! Mr. Henchard—”

‘Well,” I said, “when he comes back, I’m going to ask him what the hell. He can’t keep pixies. It isn’t in the lease.”

“He doesn’t have a lease,” Jackie countered.

I examined the little house in the bird cage. No sound, no movement. Smoke coming from the chimney.

After all, we had no right to break into the cage. Housebreaking? I had visions of a little green man with wings flourishing a night stick, arresting me for burglary. Did pixies have cops? What sort of crimes.

I put the cover back on the cage. After a while, vague noises emerged. Scrape. Thump. Rustle, rustle, rustle. Pop. And an unbirdlike trilling that broke off short.

“Oh, my,” Jackie said. “Let’s go away quick.”

We went right to bed. I dreamed of a horde of little green guys in Mack Sennett cop uniforms, dancing on a bilious rainbow and singing gaily.

The alarm clock woke me. I showered, shaved and dressed, thinking of the same thing Jackie was thinking of. As we put on our coats, I met her eyes and said, “Shall we?”

“Yes. Oh, golly, Eddie! D-do you suppose they’ll be leaving for work, too?”

“What sort of work?” I inquired angrily. “Painting buttercups?”

There wasn’t a sound from beneath the cretonne when we tiptoed into Mr. Henchard’s room. Morning sunlight blazed through the window. I jerked the cover off. There was the house. One of the blinds was up; all the rest were tightly firm. I put my head close to the cage and stared through the bars into the open window, where scraps of chintz curtains were blowing in the breeze.

I saw a great big eye looking back at me.

This time Jackie was certain I’d got my mortal wound. The breath went out of her with a whoosh as I caromed back, yelling about a horrible blood-shot eye that wasn’t human. We clutched each other for a while and then I looked again.

“Oh,” I said, rather faintly. “It’s a mirror.”

“A mirror?” she gasped.

“Yeah, a big one, on the opposite wall. That’s all I can see. I can’t get close enough to the window.”

“Look on the porch,” Jackie said.

I looked. There was a milk bottle standing by the door—you can guess the size of it. It was purple. Beside it was a folded postage stamp.

“Purple milk?” I said.

“From a purple cow. Or else the bottle’s colored. Eddie, is that a newspaper?”

It was. I strained my eyes to read the headlines. EXTRA was splashed redly across the sheet, in huge letters nearly a sixteenth of an inch high. EXTRA—FOTZPA MOVES ON TUR! That was all we could make out.

I put the cretonne gently back over the cage. We went down to Terry’s for breakfast while we waited for the bus.

When we rode home that night, we knew what our first job would be. We let ourselves into the house, discovered that Mr. Henchard hadn’t come back yet, switched on the light in his room, and listened to the noise from the bird cage.

“Music,” Jackie said.

It was so faint I scarcely heard it, and, in any case, it wasn’t real music. I can’t begin to describe it. And it died away immediately. Thump, scrape, pop, buzz. Then silence, and I pulled off the cover.

The house was dark, the windows were shut, the blinds were down. Paper and milk bottle were gone from the porch. On the front door was a sign that said—after I used a magnifying glass: QUARANTINE! SCOPPY FEVER!

“Why, the little liars,” I said. “I bet they haven’t got scoppy fever at all.”

Jackie giggled wildly. “You only get scoppy fever in April, don’t you?”

“April and Christmas. That’s when the bread-and-butter flies carry it. Where’s my pencil?”

I rang the bell. A shade twitched aside, flipped back; neither of us had seen the—hand?—that moved it. Silence; no smoke coming out of the chimney.

“Scared?” I asked.

“No. It’s funny, but I’m not. They’re such standoffish little guys. The Cabots speak only to—”

“Where the pixies speak only to goblins, you mean,” I said. “They can’t snoot us this way. It’s our house their house is in, if you follow me.”

“What can we do?”

I manipulated the pencil, and, with considerable difficulty, wrote LET US IN on the white panel of the door. There wasn’t room for more than that. Jackie tsked.

“Maybe you shouldn’t have written that. We don’t want to get in. We just want to see them.”

“Too late now. Besides, they’ll know what we mean.”

We stood watching the house in the bird cage, and it watched us, in a sullen and faintly annoyed fashion. SCOPPY FEVER, indeed!

That was all that happened that night.

The next morning we found that the tiny front door had been scrubbed clean of my pencil marks, that the quarantine’ sign was still there, and that there was a bottle of green milk and another paper on the porch. This time the headline said. EXTRA—FOTZPA OVERSHOOTS TUR!

Smoke was idling from the chimney. I rang the bell again. No answer. I noticed a domino of a mailbox by the door, chiefly because I could see through the slot that there were letters inside. But the thing was locked.

“If we could see whom they were addressed to—” Jackie suggested.

“Or whom they’re from. That’s what interests me.”

Finally, we went to work. I was preoccupied all day, and nearly welded my thumb onto a boogie-arm. When I met Jackie that night, I could see that she’d been bothered, too.

“Let’s ignore them,” she said as we bounced home on the bus. “We know when we’re not wanted, don’t we?”

“I’m not going to be high-hatted by a—by a critter. Besides, we’ll both go quietly nuts if we don’t find out what’s inside that house. Do you suppose Mr. Herichard’s a wizard?”

“He’s a louse,” Jackie said bitterly. “Going off and leaving ambiguous pixies on our hands!”

When we got home, the little house in the bird cage took alarm, as usual, and by the time we’d yanked off the cover, the distant, soft noises had faded into silence. Lights shone through the drawn blinds. The porch had only the mat on it. In the mailbox we could see the yellow envelope of a telegram.

Jackie turned pale. “It’s the last straw,” she insisted. “A telegram!”

“It may not be.”

“It is, it is, I know it is. Aunt Tinker Bell’s dead. Or Iolanthe’s coming for a visit.”

“The quarantine sign’s off the door,” I said. “There’s a new one. It says ‘wet paint.’”

“Well, you will scribble all over their nice clean door.”

I put the cretonne back, turned off the light switch, and took Jackie’s hand. We stood waiting. After a time something went bump-bump-bump, and then there was a singing, like a tea-kettle. I heard a tiny clatter.

Next morning there were twenty-six bottles of yellow milk—bright yellow—on the tiny porch, and the Lilliputian headline announced:

EXTRA—TUR SLIDES TOWARD FOTZPA!

There was mail in the box, too, but the telegram was gone.

That night things continued much as before. When I pulled the cloth off there was a sudden, furious silence. We felt that we were being watched around the corners of the miniature shades. We finally went to bed, but in the middle of the night I got up and took another look at our mysterious tenants. Not that I saw them, of course. But they must have been throwing a party, for bizarre, small music and wild thumps and pops died into silence as I peeked.