The White Horses

Halliwell Sutcliffe

Produced by Al Haines.

"Old Squire Metcalf, as he went out to meet him, brokeinto a roar of laughter." (Page 84.)]

THE WHITE HORSES

BY

HALLIWELL SUTCLIFFE

_Author of "Ricroft of Withers," "The Open Road," "A Chateau in Picardy," "The Strength of the Hills," etc._

WARD, LOCK & CO., LIMITED LONDON, MELBOURNE AND TORONTO 1916

To my Sister's Memory

*CONTENTS.*

CHAPTER

I.--WHO RIDES FOR THE KING?II.--SKIPTON-IN-CRAVENIII.--SOME MEN OF FAIRFAX'SIV.--THE LAST LAUGHV.--THE LADY OF RIPLEYVI.--HOW MICHAEL CAME TO YORKVII.--A HALT AT KNARESBOROUGHVIII.--HOW THEY SOUGHT RUPERTIX.--THE LOYAL CITYX.--THE RIDING INXI.--BANBURY CAKESXII.--PAGEANTRYXIII.--THE LADY OF LATHOMXIV.--A STANLEY FOR THE KINGXV.--TWO JOLLY PURITANSXVI.--THE SCOTS AT MICKLEGATEXVII.--PRAYER, AND THE BREWING STORMXVIII.--MARSTON MOORXIX.--WILSTROP WOODXX.--THE HOMELESS DAYSXXI.--SIR REGINALD'S WIDOWXXII.--MISS BINGHAMXXIII.--YOREDALE

*Illustrations*

"Old Squire Metcalf, as he went out to meet him, broke into a roar oflaughter." . . . . . . _Frontispiece_ (Page 84.)

"'You're the Squire of Nappa, sir?' he said."

"'Yes, you can be of service,' he whispered."

"'Say, do you stand for the King?'"

"Without a word of any kind, a third prisoner was thrown against them."

"They saw, too, that his sword was out, and naked to the moonlight."

"'Well, sir?' she asked sharply. 'You rob me of sleep for some goodreason doubtless?'"

"They turned sharply as the door opened, and reached out for theirweapons."

"'We hold your life at our mercy,' said Rupert."

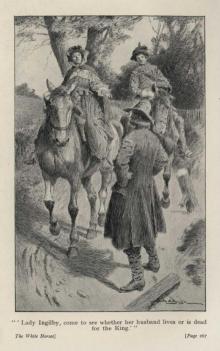

"'Lady Ingilby, come to see whether her husband lives or is dead for theKing.'"

"'If the end of the world came--here and now--you would make a jest ofit.'"

"Her eyes searched eagerly for one only of the company, and disdainedthe rest."

*THE WHITE HORSES.*

*CHAPTER I.*

*WHO RIDES FOR THE KING?*

Up through the rich valley known now as Wensleydale, but in those daysmarked by the lustier name of Yoredale, news had crept that there wascivil war in England, that sundry skirmishes had been fought already,and that His Majesty was needing all leal men to rally to his standard.

It was an early harvest that year, as it happened, and John Metcalf, ofNappa Hall, stood at his garden-gate, watching the sunset glow acrosshis ripening wheat. There were many acres of it, gold between greensplashes of grass-land; and he told himself that they would put thesickle into the good crop before a fortnight's end. There was somethingabout Squire Metcalf--six feet four to his height, and broad in thebeam--that seemed part of the wide, lush country round him. Weather andland, between them, had bred him; and the night's peace, the smell ofsweet-briar in the evening dew, were pleasant foils to his strength.

He looked beyond the cornfields presently. Far down the road he saw ahorseman--horse and rider small in the middle of the landscape--andwondered what their errand was. When he had done with surmises, hisglance roved again, in the countryman's slow way, and rested on thepastures above the house. In the clear light he could see two figuresstanding there; one was his son Christopher, the other a trim-waistedmaid. Squire Metcalf frowned suddenly. He was so proud of his name, ofhis simple squiredom, that he could not bear to see his eldest-borncourting defeat of this kind. This little lady was niece to hisneighbour, Sir Timothy Grant, a good neighbour and a friend, but one whowas richer than himself in lands and rank, one who went often to theCourt in London, and was in great favour with the King. Squire Metcalfhad seen these two together in his own house, and guessed Christopher'ssecret without need of much sagacity; and he was sorely troubled on thelad's account.

Christopher himself, away at the stile yonder, was not troubled at allexcept by a pleasant heartache. He had youth, and Joan Grant beside him,and a heart on fire for her.

"You are pleased to love me?" she was saying, facing him with maddeninggrace. "What is your title to love me, sir?"

"Any man has the right to love," Kit protested sturdily. "He cannothelp it sometimes."

"Oh, granted; but not to tell it openly."

"What else should a man do? I was never one for secrets."

Joan laughed pleasantly, as if a thrush were singing. "You speak truth.I would not trust you with a secret as far as from here to Nappa. If achild met you on the road, she would read it in your face."

"I was bred that way, by your leave. We Metcalfs do not fear thelight."

"But, sir, you have every right to--to think me better than I am, butnone at all to speak of--of love. I had an old Scots nurse to teach mewisdom, and she taught me--what, think you?"

"To thieve and raid down Yoredale," said Kit unexpectedly. "The Scotshad only that one trade, so my father tells me, till the Stuarts came toreign over both countries."

"To thieve and raid? And I--I, too, have come to raid, you say--tosteal your heart?"

"You are very welcome to it."

"But do I want it?" She put aside her badinage, drew away from him witha fine strength and defiance. "Listen, sir. My Scots nurse taught methat a woman has only one heart to give in her lifetime; that, for herpeace, she must hide it in the branches of a tree so high that only astrong man can climb it."

"I'm good at tree-climbing," said Christopher, with blunt acceptance ofthe challenge.

"Then prove it."

"Now?" he asked, glancing at a tall fir behind them.

"Oh, sir, you are blunt and forthright, you men of Nappa! You do notunderstand the heart of a woman."

Kit Metcalf stood to his brawny six-foot height. "I'm needing you, andcannot wait," he said, fiery and masterful. "That's the way of a man'sheart."

"Then, by your leave, I shall bid you good e'en. No man will ever masterme until----"

"Until?" asked Kit, submissive now that he saw her retreating up thepasture.

She dropped him another curtsey before going up the steep face of thehills. "That is the woman's secret, sir. It lives at the top of a hightree, that 'until.' Go climbing, Master Christopher!"

Kit went back to Nappa, in frank revolt against destiny and the blueface of heaven. There was nothing in the world worth capturing exceptthis maid who eluded him at every turn, like a butterfly swift of wing.He was prepared to be sorry for himself until he came face to face withhis father at the garden gate.

"I saw two young fools at the stile," said Squire Metcalf. "I'vewatched you for half an hour. Best wed in your own station, Kit--nomore, no less. No Metcalf ever went dandying after great ladies yet.We've our own proper pride."

Christopher, in spite of his six feet, looked a small man as he stoodbeside his father; but his spirit was equal to its stubborn strength."I love her. There's no other for me," he said sharply.

The Squire glanced shrewdly at him. "Ah, well," he said at last, "if itgoes as deep as that, lad, you'll just have to go on crying out for themoon. Sir Timothy has been away in London all the summer--trouble withthe Parliament, and the King needing him, they say. He'd have takenMiss Joan with him if he'd guessed that a lad from Nappa thought hecould ever wed into the family."

"We've lands and gear enough," protested Kit.

"We have, but not as they count such matters. They've got one foot inYoredale, and t'other in Lo

ndon; and we seem very simple to them, Kit."

Shrewd common sense is abhorrent to all lovers, and Kit fell into astormy silence. He knew it true, that he felt rough, uncouth, inpresence of his mistress; but he knew also that at the heart of himthere was a love that was not uncouth at all.

The Squire left Kit to fight out his own trouble, and fell to watchingthe horseman who was more than a speck now on the landscape. The ridershowed as a little man striding a little mare; both were weary, by thelook of them, and both were heading straight for Nappa Hall. They had amile to cover.

"Father, I need to get away from Nappa," said Kit, breaking the silence.

"Ay," said the Squire, with a tolerant laugh, "love takes all men thatway in the first flush of it. I was young myself once. You want to rideout, lad, and kill a few score men, just to show little Miss Joan what alikely man o' your hands you are. Later on, you'll be glad to beshepherding the ewes, to pay for her new gowns and what not. Love's notall mist and moonshine, Kit; the sturdier part comes later on."

Up the lane sounded the lolopping pit-a-pat of a horse that was tiredout and near to drop; and the rider looked in no better case as he drewrein at the gate.

"You're the Squire of Nappa, sir?" he said, with a weary smile. "Noweary to ask the question. I was told to find a man as tall as anoak-tree and as sturdy."

"'You're the Squire of Nappa, sir?' he said."]

"Yet it would have been like seeking a needle in a bundle of hay, if youhadn't chanced to find me at the gate," the other answered. "There aresix score Metcalfs in this corner of Yoredale, and nobody takes noticeof my height."

"The jest is pretty enough, sir, but you'll not persuade me that there'sa regiment of giants in the dale."

"They're not all of my height--granted. Some are more, and a few less.This is my eldest-born," he said, touching Christopher on the shoulder."We call him Baby Kit, because he's the smallest of us all."

The horseman saw a lad six foot high, who certainly looked dwarfed as hestood beside his father. "Gad, the King has need of you! Undoubtedly heneeds all Metcalfs, if this is your baby-boy."

"As for the King, the whole six score of us have prayed for his welfare,Sabbath in and Sabbath out, since we were breeked. It's good hearingthat he needs us."

"I ride on His Majesty's errand. He bids the Squire of Nappa get hismen and his white horses together."

"So the King has heard of our white horses? Well, we're proud o' them, Iown."

The messenger, used to the stifled atmosphere of Courts until thistrouble with the Parliament arrived, was amazed by the downright,free-wind air the Squire of Nappa carried. It tickled his humour, tiredas he was, that Metcalf should think the King himself knew every detailof his country, and every corner of it that bred white horses, or roan,or chestnut. At Skipton-in-Craven, of course, they knew the dales fromend to end; and he was here because Sir John Mallory, governor of thecastle there, had told him the Metcalfs of Nappa were slow to leave thebeaten tracks, but that, once roused, they would not budge, or falter,or retreat.

"The King needs every Metcalf and his white horse. He sent me with thatmessage to you, Squire."

"About when does he need us?" asked Metcalf guardedly.

"To-morrow, to be precise."

"Oh, away with you! There's all my corn to be gathered in. I'll comenearer the back end o' the year, if the King can bide till then. Bythat token, you're looking wearied out, you and your horse. Comeindoors, man, and we'll talk the matter over."

The messenger was nothing loath. At Skipton they had given animportance to the Metcalf clan that he had not understood till now.This was the end of to-day's journey, and his sole errand was to bringthe six score men and horses into the good capital of Craven.

"I ask no better cheer, sir. Can you stable the two of us for thenight? My little grey mare is more in need of rest than I am."

Christopher, the six-foot baby of the clan, ran forward to the mare'sbridle; and he glanced at his father, because the war in his blood wasvehement and lusty, and he feared the old check of discipline.

"Is it true, sir?" he asked the messenger. "Does the King need us?I've dreamed of it o' nights, and wakened just to go out and tend theland. I'm sick of tending land. Is it true the King needs us?"

The messenger, old to the shams and false punctilios of life, wasdismayed for a moment by this clean, sturdy zest. Here, he toldhimself, was a cavalier in the making--a cavalier of Prince Rupert'sbreed, who asked only for the hazard.

"It is true that the King needs a thousand such as you," he said drily."Be good to my little mare; I trust her to you, lad."

And in this solicitude for horseflesh, shown twice already, themessenger had won his way already into the favour of all Metcalfs. Forthey loved horses just a little less than they loved their King.

Within doors, as he followed the Squire of Nappa, he found a warm fireof logs, and an evening meal to which the sons of the house trooped inat haphazard intervals. There were only six of them, all told, but theyseemed to fill the roomy dining-room as if a crowd intruded. Therafters of the house were low, and each stooped, from long habit, as hecame in to meat. Kit, the baby of the flock, was the last to come in;and he had a queer air about him, as if he trod on air.

There was only one woman among them, a little, eager body, who welcomedthe stranger with pleasant grace. She had borne six sons to the Squire,because he was dominant and thought little of girl-children; she hadgone through pain and turmoil for her lord, and at the end of it wasthankful for her pride in him, though she would have liked to find onegirl among the brood--a girl who knew the way of household worries andthe way of women's tears.

The messenger, as he ate and drank with extreme greediness, because needasked, glanced constantly at the hostess who was like a garden flower,growing here under the shade of big-boled trees. It seemed impossiblethat so small a person was responsible for the six men who made therafters seem even lower than they were.

When the meal was ended, Squire Metcalf put his guest into the greathooded chair beside the fire of peat and wood.

"Now, sir, we'll talk of the King, by your leave, and these lusty roguesof mine shall stand about and listen. What is it His Majesty asks ofus?"

The messenger, now food and liquor had given him strength again, felt athome in this house of Nappa as he had never done among the intrigues ofCourt life. He had honest zeal, and he was among honest men, and histongue was fiery and persuasive.

"The King needs good horsemen and free riders to sweep the land clear ofRoundheads. He needs gentlemen with the strong arm and the simple heartto fight his battles. The King--God bless him!--needs six-scoreMetcalfs, on horses as mettled as their riders, to help put out thiscursed fire of insurrection."

"Well, as for that," said the Squire, lighting his pipe with a live peatfrom the hearth, "I reckon we're here for that purpose. I bred my sonsfor the King, when he was pleased to need them. But I'd rather he couldbide--say, for a month--till we get our corn in. Take our six-score menfrom the land just now, and there'll be no bread for the house nextyear, let alone straw for the beasts."

The messenger grew more and more aware that he had been entrusted with afine mission. This plain, unvarnished honesty of the Squire's was worthfifty protestations of hot loyalty. The dogged love he had of his landsand crops--the forethought of them in the midst of civil war--would makehim a staunch, cool-headed soldier.

"The King says you are to ride out to-morrow, Squire. What use to prayfor him on Sabbaths if you fail him at the pinch?"

Metcalf was roused at last, but he glanced at the little wife who satquietly in her corner, saying little and feeling much. "I've more thanharvesting to leave. She's small, that wife of mine, but God knows thebig love I have for her."

The little woman got up suddenly and stepped forward through the pressof big sons she had reared. Her man said openly that he loved her betterthan his lands, and she had doubted it till now. She came and stoodbefore the

messenger and dropped him a curtsey.

"You are very welcome, sir, to take all my men on the King's service.What else? I, too, have prayed on Sabbaths."

The messenger rose, a great pity and chivalry stirring through hishard-ridden, tired body. "And you, madam?" he asked gently.

"Oh, I shall play the woman's part, I hope--to wait, and be silent, andshed tears when there are no onlookers."

"By God's grace," said Blake, the messenger, a mist about his eyes, "Ihave come to a brave house!"

The next morning, an hour after daybreak, Blake awoke, stirred drowsily,then sprang out of bed. Sleep was a luxury to him these days, and heblamed himself for indolence.

Downstairs he found only a serving-maid, who was spreading the breakfasttable with cold meats enough to feed twenty men of usual size andappetite. The mistress was in the herb-garden, she said, and the menfolk all abroad.

For a moment the messenger doubted his welcome last night. Had hedreamed of six score men ready for the King's service, or was theSquire's honesty, his frank promise to ride out, a pledge repented ofalready?

He found the Squire's wife walking in the herb-garden, and the face shelifted was tear-stained. "I give you good day," she said, "thoughyou've not dealt very well with me and mine."

"Is there a finer errand than the King's?" he asked brusquely.

"My heart, sir, is not concerned with glory and fine errands. It isvery near to breaking. Without discourtesy, I ask you to leave me herein peace--for a little while--until my wounds are healing."

The Squire and his sons had been abroad before daybreak, riding outacross the wide lands of Nappa. Of the hundred odd grown men on theiracres, there was not one--yeoman, or small farmer, or hind--but was aMetcalf by name and tradition. They were a clan of the old, tough Bordersort, welded together by a loyalty inbred through many generations; andthe law that each man's horse must be of the true Metcalf white was notof yesterday.

Christopher's ride to call his kinsfolk in had taken him wide to theboundary of Sir Timothy Grant's lands; and, as he trotted at the head ofhis growing company, he was bewildered to see Joan step from a littlecoppice on the right of the track. She had been thinking of him, as ithappened, till sleep would not come; and, like himself, she needed toget out into the open. Very fresh she looked, as she stepped into themisty sunlight--alert, free-moving, bred by wind and rain and sun. ToKit she seemed something not of this world; and it is as well, maybe,that a boy's love takes this shape, because in saner manhood the glamourof the old day-dreams returns, to keep life wholesome.

Kit halted his company, heedless of their smiles and muttered jests, ashe rode to her side.

"You look very big, Christopher! You Nappa men--and your horses--areyou riding to some hunt?" She was cold, provocative, dismaying.

"Yes, to hunt the Roundheads over Skipton way. The King has sent forus."

"But--the call is so sudden, and--I should not like to hear that youwere dead, Kit."

Her eyes were tender with him, and then again were mocking. He couldmake nothing her, as how should he, when older men than he had failed tounderstand the world's prime mystery.

"Joan, what did you mean by 'until,' last night at the stile? You saidnone should master you until----"

"Why, yes, _until_---- Go out and find the answer to that riddle."

"Give me your kerchief," he said sharply--"for remembrance, Joan."

Again she resented his young, hot mastery, peeping out through thebondage she had woven round him. "To wear at your heart? But, Kit, youhave not proved your right to wear it. Come back from slayingRoundheads, and ask for it again."

Blake, the messenger, meanwhile, had been fidgeting about the Nappagarden, wondering what was meant by the absence of all men from houseand fields. His appetite, too, was sharpened by a sound night's sleep.Remembering the well-filled table indoors, he turned about, then checkedhimself with a laugh. Even rough-riding gentry could not break fastuntil the host arrived.

Presently, far down the road, he heard the lilt of horse-hoofs movingswiftly and in tune. The uproar grew, till round the bend of the way hesaw what the meaning of it was.

Big men on big white horses came following the Squire of Nappa up therise. All who could gather in the courtyard reined up; the rest of thehundred and twenty halted in the lane. They had rallied to the musterwith surprising speed, these men of Yoredale.

All that the messenger had suffered already for the cause, all that hewas willing to suffer later on, were forgotten. Here were volunteersfor the King--and, faith, what cavaliers they were! And the big men,striding their white horses, liked him the better because his heartshowed plainly in his face.

The messenger laughed suddenly, standing to the the height offive-foot-six that was all Providence had given him. "Gentlemen," hesaid, with the music of galloping horses in his voice, "gentlemen, theKing!"

The Squire and he, after they had breakfasted, and the mistress hadcarried the stirrup-cup from one horseman to another, rode forwardtogether on the track that led to Skipton. For a mile they went insilence. The Squire of Nappa was thinking of his wife, and youngstersof the Metcalf clan were thinking of maids who had lately glamoured themin country lanes. Then the lilt of hoof-beats, the call of the openhazard, got into their blood. A lad passed some good jest, till it ranalong the company like fire through stubble; and after that each manrode blithely, as if it were his wedding-day.

A mile further on they saw a little lady gathering autumn flowers fromthe high bank bordering the road. She had spent a restless night onKit's account, had he known it, and was early abroad struggling withmany warring impulses. The Squire, who loved Christopher, knew what thelad most needed now. He drew rein sharply.

"Men of Nappa, salute!" he cried, his voice big and hearty as his body.

Joan Grant, surprised in the middle of a love-dream, saw a hundred andtwenty men lifting six-foot pikes to salute her. The stress of it wasso quick and overwhelming that it braced her for the moment. She tookthe salute with grace and a smile that captured these rough-ridinggentry. Then, with odd precision, she dropped her kerchief under thenose of Kit's horse.

He stooped sharply and picked it up at the end of his pike. "A goodomen, lads!" he cried. "White horses--and the white kerchief for theKing!"

Then it was forward again; and Joan, looking after them, was aware thatalready her knight was in the making. And then she fell into a flood oftears, because women are made up of storm and sun, like the queernorthern weather.