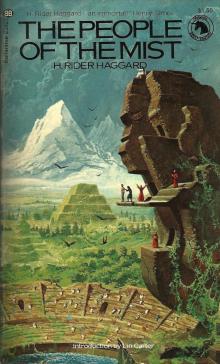

The People of the Mist

H. Rider Haggard

Produced by John Bickers; Dagny

THE PEOPLE OF THE MIST

By H. Rider Haggard

First Published 1894.

DEDICATION

I DEDICATE THIS EFFORT OF"PRIMEVAL AND TROGLODYTE IMAGINATION"THIS RECORD OF BAREFACED AND FLAGRANT ADVENTURE

TO MY GODSONS

IN THE HOPE THAT THEREIN THEY MAY FINDSOME STORE OF HEALTHY AMUSEMENT.

_Ditchingham_, 1894.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

On several previous occasions it has happened to this writer of romanceto be justified of his romances by facts of startling similarity,subsequently brought to light and to his knowledge. In this tale occursan instance of the sort, a "double-barrelled" instance indeed, that tohim seems sufficiently curious to be worthy of telling. The People ofthe Mist of his adventure story worship a sacred crocodile to which theymake sacrifice, but in the original draft of the book this crocodile wasa snake--_monstrum horrendum, informe, ingens_. A friend of the writer,an African explorer of great experience who read that draft, suggestedthat the snake was altogether too unprecedented and impossible.Accordingly, also at his suggestion, a crocodile was substituted.Scarcely was this change effected, however, when Mr. R. T. Coryndon, theslayer of almost the last white rhinoceros, published in the _AfricanReview_ of February 17, 1894, an account of a huge and terrific serpentsaid to exist in the Dichwi district of Mashonaland, that in manyparticulars resembled the snake of the story, whose prototype, by theway, really lives and is adored as a divinity by certain natives in theremote province of Chiapas in Mexico. Still, the tale being in type, thealteration was suffered to stand. But now, if the _Zoutpansberg Review_may be believed, the author can take credit for his crocodile also,since that paper states that in the course of the recent campaignagainst Malaboch, a chief living in the north of the Transvaal, hisfetish or god was captured, and that god, a crocodile fashioned in wood,to which offerings were made. Further, this journal says that amongthese people (as with the ancient Egyptians), the worship of thecrocodile is a recognised cult. Also it congratulates the present writeron his intimate acquaintance with the more secret manifestations ofAfrican folklore and beast worship. He must disclaim the compliment inthis instance as, when engaged in inventing the 'People of the Mist,'he was totally ignorant that any of the Bantu tribes reverenced eithersnake or crocodile divinities. But the coincidence is strange, and oncemore shows, if further examples of the fact are needed, how impotentare the efforts of imagination to vie with hidden truths--even with thehidden truths of this small and trodden world.

_September_ 20, 1894.

THE PEOPLE OF THE MIST

CHAPTER I

THE SINS OF THE FATHER ARE VISITED ON THE CHILDREN

The January afternoon was passing into night, the air was cold andstill, so still that not a single twig of the naked beech-trees stirred;on the grass of the meadows lay a thin white rime, half frost, halfsnow; the firs stood out blackly against a steel-hued sky, and over thetallest of them hung a single star. Past these bordering firs there rana road, on which, in this evening of the opening of our story, a youngman stood irresolute, glancing now to the right and now to the left.

To his right were two stately gates of iron fantastically wrought,supported by stone pillars on whose summits stood griffins of blackmarble embracing coats of arms, and banners inscribed with the device_Per ardua ad astra_. Beyond these gates ran a broad carriage drive,lined on either side by a double row of such oaks as England alone canproduce under the most favourable circumstances of soil, aided by thenurturing hand of man and three or four centuries of time.

At the head of this avenue, perhaps half a mile from the roadway,although it looked nearer because of the eminence upon which it wasplaced, stood a mansion of the class that in auctioneers' advertisementsis usually described as "noble." Its general appearance was Elizabethan,for in those days some forgotten Outram had practically rebuilt it; buta large part of its fabric was far more ancient than the Tudors,dating back, so said tradition, to the time of King John. As we arenot auctioneers, however, it will be unnecessary to specify its manybeauties; indeed, at this date, some of the tribe had recently employedtheir gift of language on these attractions with copious fulness andaccuracy of detail, since Outram Hall, for the first time during sixcenturies, was, or had been, for sale.

Suffice it to say that, like the oaks of its avenue, Outram was sucha house as can only be found in England; no mere mass of bricksand mortar, but a thing that seemed to have acquired a life andindividuality of its own. Or, if this saying be too far-fetched andpoetical, at the least this venerable home bore some stamp and traceof the lives and individualities of many generations of mankind, linkedtogether in thought and feeling by the common bond of blood.

The young man who stood in the roadway looked long and earnestly towardsthe mass of buildings that frowned upon him from the crest of the hill,and as he looked an expression came into his face which fell little, ifat all, short of that of agony, the agony which the young can feel atthe shock of an utter and irredeemable loss. The face that wore suchevidence of trouble was a handsome one enough, though just now all thecharm of youth seemed to have faded from it. It was dark and strong, norwas it difficult to guess that in after-life it might become stern. Theform also was shapely and athletic, though not very tall, giving promiseof more than common strength, and the bearing that of a gentleman whohad not brought himself up to the belief that ancient blood can covermodern deficiencies of mind and manner. Such was the outward appearanceof Leonard Outram as he was then, in his twenty-third year.