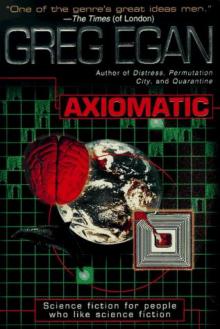

Axiomatic

Greg Egan

Axiomatic

Greg Egan

Derived from the 2008 reissue published by Gollancz, London

ISBN 9780575081741

Originally published in 1995

The Infinite Assassin

One thing never changes: when some mutant junkie on S starts shuffling reality, it’s always me they send into the whirlpool to put things right.

Why? They tell me I’m stable. Reliable. Dependable. After each debriefing, The Company’s psychologists (complete strangers, every time) shake their heads in astonishment at their printouts, and tell me that I’m exactly the same person as when ‘I’ went in.

The number of parallel worlds is uncountably infinite—infinite like the real numbers, not merely like the integers—making it difficult to quantify these things without elaborate mathematical definitions, but roughly speaking, it seems that I’m unusually invariant: more alike from world to world than most people are. How alike? In how many worlds? Enough to be useful. Enough to do the job.

How The Company knew this, how they found me, I’ve never been told. I was recruited at the age of nineteen. Bribed. Trained. Brainwashed, I suppose. Sometimes I wonder if my stability has anything to do with me; maybe the real constant is the way I’ve been prepared. Maybe an infinite number of different people, put through the same process, would all emerge the same. Have all emerged the same. I don’t know.

* * *

Detectors scattered across the planet have sensed the faint beginnings of the whirlpool, and pinned down the centre to within a few kilometres, but that’s the most accurate fix I can expect by this means. Each version of The Company shares its technology freely with the others, to ensure a uniformly optimal response, but even in the best of all possible worlds, the detectors are too large, and too delicate, to carry in closer for a more precise reading.

A helicopter deposits me on wasteland at the southern edge of the Leightown ghetto. I’ve never been here before, but the boarded-up shopfronts and grey tower blocks ahead are utterly familiar. Every large city in the world (in every world I know) has a place like this, created by a policy that’s usually referred to as differential enforcement. Using or possessing S is strictly illegal, and the penalty in most countries is (mostly) summary execution, but the powers that be would rather have the users concentrated in designated areas than risk having them scattered amongst the community at large. So, if you’re caught with S in a nice clean suburb, they’ll blow a hole in your skull on the spot, but here, there’s no chance of that. Here, there are no cops at all.

I head north. It’s just after four a.m., but savagely hot, and once I move out of the buffer zone, the streets are crowded. People are coming and going from nightclubs, liquor stores, pawn shops, gambling houses, brothels. Power for street lighting has been cut off from this part of the city, but someone civic-minded has replaced the normal bulbs with self-contained tritium/phosphor globes, spilling a cool, pale light like radioactive milk. There’s a popular misconception that most S users do nothing but dream, twenty-four hours a day, but that’s ludicrous; not only do they need to eat, drink and earn money like everyone else, but few would waste the drug on the time when their alter egos are themselves asleep.

Intelligence says there’s some kind of whirlpool cult in Leightown, who may try to interfere with my work. I’ve been warned of such groups before, but it’s never come to anything; the slightest shift in reality is usually all it takes to make such an aberration vanish. The Company, the ghettos, are the stable responses to S; everything else seems to be highly conditional. Still, I shouldn’t be complacent. Even if these cults can have no significant impact on the mission as a whole, no doubt they have killed some versions of me in the past, and I don’t want it to be my turn, this time. I know that an infinite number of versions of me would survive—some whose only difference from me would be that they had survived—so perhaps I ought to be entirely untroubled by the thought of death.

But I’m not.

Wardrobe have dressed me with scrupulous care, in a Fat Single Mothers Must Die World Tour souvenir reflection hologram T-shirt, the right style of jeans, the right model running shoes. Paradoxically, S users tend to be slavish adherents to ‘local’ fashion, as opposed to that of their dreams; perhaps it’s a matter of wanting to partition their sleeping and waking lives. For now, I’m in perfect camouflage, but I don’t expect that to last; as the whirlpool picks up speed, sweeping different parts of the ghetto into different histories, changes in style will be one of the most sensitive markers. If my clothes don’t look out of place before too long, I’ll know I’m headed in the wrong direction.

A tall, bald man with a shrunken human thumb dangling from one ear lobe collides with me as he runs out of a bar. As we separate, he turns on me, screaming taunts and obscenities. I respond cautiously; he may have friends in the crowd, and I don’t have time to waste getting into that kind of trouble. I don’t escalate things by replying, but I take care to appear confident, without seeming arrogant or disdainful. This balancing act pays off. Insulting me with impunity for thirty seconds apparently satisfies his pride, and he walks away smirking.

As I move on, though, I can’t help wondering how many versions of me didn’t get out of it so easily.

I pick up speed to compensate for the delay.

Someone catches up with me, and starts walking beside me. ‘Hey, I liked the way you handled that. Subtle. Manipulative. Pragmatic. Full marks.’ A woman in her late twenties, with short, metallic-blue hair.

‘Fuck off. I’m not interested.’

‘In what?’

‘In anything.’

She shakes her head. ‘Not true. You’re new around here, and you’re looking for something. Or someone. Maybe I can help.’

‘I said, fuck off.’

She shrugs and falls behind, but calls after me, ‘Every hunter needs a guide. Think about it.’

* * *

A few blocks later, I turn into an unlit side street. Deserted, silent; stinking of half-burnt garbage, cheap insecticide, and piss. And I swear I can feel it: in the dark, ruined buildings all around me, people are dreaming on S.

S is not like any other drug. S dreams are neither surreal nor euphoric. Nor are they like simulator trips: empty fantasies, absurd fairy tales of limitless prosperity and indescribable bliss. They’re dreams of lives that, literally, might have been lived by the dreamers, every bit as solid and plausible as their waking lives.

With one exception: if the dream life turns sour, the dreamer can abandon it at will, and choose another (without any need to dream of taking S… although that’s been known to happen). He or she can piece together a second life, in which no mistakes are irrevocable, no decisions absolute. A life without failures, without dead ends. All possibilities remain forever accessible.

S grants dreamers the power to live vicariously in any parallel world in which they have an alter ego—someone with whom they share enough brain physiology to maintain the parasitic resonance of the link. Studies suggest that a perfect genetic match isn’t necessary for this—but nor is it sufficient; early childhood development also seems to affect the neural structures involved.

For most users, the drug does no more than this. For one in a hundred thousand, though, dreams are only the beginning. During their third or fourth year on S, they start to move physically from world to world, as they strive to take the place of their chosen alter egos.

The trouble is, there’s never anything so simple as an infinity of direct exchanges, between all the versions of the mutant user who’ve gained this power, and all the versions they wish to become. Such transitions are energetically unfavourable; in practice, each dreamer must move gradually, continuously, passing through all the intervening points. But those ‘points’ are occupied b

y other versions of themselves; it’s like motion in a crowd—or a fluid. The dreamers must flow.

At first, those alter egos who’ve developed the skill are distributed too sparsely to have any effect at all. Later, it seems there’s a kind of paralysis through symmetry; all potential flows are equally possible, including each one’s exact opposite. Everything just cancels out.

The first few times the symmetry is broken, there’s usually nothing but a brief shudder, a momentary slippage, an almost imperceptible world-quake. The detectors record these events, but are still too insensitive to localise them.

Eventually, some kind of critical threshold is crossed. Complex, sustained flows develop: vast, tangled currents with the kind of pathological topologies that only an infinite-dimensional space can contain. Such flows are viscous; nearby points are dragged along. That’s what creates the whirlpool; the closer you are to the mutant dreamer, the faster you’re carried from world to world.

As more and more versions of the dreamer contribute to the flow, it picks up speed—and the faster it becomes, the further away its influence is felt.

The Company, of course, doesn’t give a shit if reality is scrambled in the ghettos. My job is to keep the effects from spreading beyond.

I follow the side street to the top of a hill. There’s another main road about four hundred metres ahead. I find a sheltered spot amongst the rubble of a half-demolished building, unfold a pair of binoculars, and spend five minutes watching the pedestrians below. Every ten or fifteen seconds, I notice a tiny mutation: an item of clothing changing; a person suddenly shifting position, or vanishing completely, or materialising from nowhere. The binoculars are smart; they count up the number of events which take place in their field of view, as well as computing the map coordinates of the point they’re aimed at.

I turn one hundred and eighty degrees, and look back on the crowd that I passed through on my way here. The rate is substantially lower, but the same kind of thing is visible. Bystanders, of course, notice nothing; as yet, the whirlpool’s gradients are so shallow that any two people within sight of each other on a crowded street would more or less shift universes together. Only at a distance can the changes be seen.

In fact, since I’m closer to the centre of the whirlpool than the people to the south of me, most of the changes I see in that direction are due to my own rate of shift. I’ve long ago left the world of my most recent employers behind—but I have no doubt that the vacancy has been, and will continue to be, filled.

I’m going to have to make a third observation to get a fix, some distance away from the north-south line joining the first two points. Over time, of course, the centre will drift, but not very rapidly; the flow runs between worlds where the centres are close together, so its position is the last thing to change.

I head down the hill, westwards.

* * *

Amongst the crowds and lights again, waiting for a gap in the traffic, someone taps my elbow. I turn, to see the same blue-haired woman who accosted me before. I give her a stare of mild annoyance, but I keep my mouth shut; I don’t know whether or not this version of her has met a version of me, and I don’t want to contradict her expectations. By now, at least some of the locals must have noticed what’s going on—just listening to an outside radio station, stuttering randomly from song to song, should be enough to give it away—but it’s not in my interest to spread the news.

She says, ‘I can help you find her.’

‘Help me find who?’

‘I know exactly where she is. There’s no need to waste time on measurements and calc—’

‘Shut up. Come with me.’

She follows me, uncomplaining, into a nearby alley. Maybe I’m being set up for an ambush. By the whirlpool cult? But the alley is deserted. When I’m sure we’re alone, I push her against the wall and put a gun to her head. She doesn’t call out, or resist; she’s shaken, but I don’t think she’s surprised by this treatment. I scan her with a hand-held magnetic resonance imager; no weapons, no booby traps, no transmitters.

I say, ‘Why don’t you tell me what this is all about?’ I’d swear that nobody could have seen me on the hill, but maybe she saw another version of me. It’s not like me to screw up, but it does happen.

She closes her eyes for a moment, then says, almost calmly, ‘I want to save you time, that’s all. I know where the mutant is. I want to help you find her as quickly as possible.’

‘Why?’

‘Why? I have a business here, and I don’t want to see it disrupted. Do you know how hard it is to build up contacts again, after a whirlpool’s been through? What do you think—I’m covered by insurance?’

I don’t believe a word of this, but I see no reason not to play along; it’s probably the simplest way to deal with her, short of blowing her brains out. I put away the gun and take a map from my pocket.

‘Show me.’

She points out a building about two kilometres north-east of where we are. ‘Fifth floor. Apartment 522.’

‘How do you know?’

‘A friend of mine lives in the building. He noticed the effects just before midnight, and he got in touch with me.’ She laughs nervously. ‘Actually, I don’t know the guy all that well… but I think the version who phoned me had something going on with another me.’

‘Why didn’t you just leave when you heard the news? Clear out to a safe distance?’

She shakes her head vehemently. ‘Leaving is the worst thing to do; I’d end up even more out of touch. The outside world doesn’t matter. Do you think I care if the government changes, or the pop stars have different names? This is my home. If Leightown shifts, I’m better off shifting with it. Or with part of it.’

‘So how did you find me?’

She shrugs. ‘I knew you’d be coming. Everybody knows that much. Of course, I didn’t know what you’d look like—but I know this place pretty well, and I kept my eyes open for strangers. And it seems I got lucky.’

Lucky. Exactly. Some of my alter egos will be having versions of this conversation, but others won’t be having any conversation at all. One more random delay.

I fold the map. ‘Thanks for the information.’

She nods. ‘Any time.’

As I’m walking away, she calls out, ‘Every time.’

* * *

I quicken my step for a while; other versions of me should be doing the same, compensating for however much time they’ve wasted. I can’t expect to maintain perfect synch, but dispersion is insidious; if I didn’t at least try to minimise it, I’d end up travelling to the centre by every conceivable route, and arriving over a period of days.

And although I can usually make up lost time, I can never entirely cancel out the effects of variable delays. Spending different amounts of time at different distances from the centre means that all the versions of me aren’t shifted uniformly. There are theoretical models which show that under certain conditions, this could result in gaps; I could be squeezed into certain portions of the flow, and removed from others—a bit like halving all the numbers between 1 and 1, leaving a hole from 0.5 to 1… squashing one infinity into another which is cardinally identical, but half the geometric size. No versions of me would have been destroyed, and I wouldn’t even exist twice in the same world, but nevertheless, a gap would have been created.

As for heading straight for the building where my ‘informant’ claims the mutant is dreaming, I’m not tempted at all. Whether or not the information is genuine, I doubt very much that I’ve received the tip-off in any but an insignificant portion—technically, a set of measure zero—of the worlds caught up in the whirlpool. Any action taken only in such a sparse set of worlds would be totally ineffectual, in terms of disrupting the flow.

If I’m right, then of course it makes no difference what I do; if all the versions of me who received the tip-off simply marched out of the whirlpool, it would have no impact on the mission. A set of measure zero wouldn’t be missed. But my actions, as

an individual, are always irrelevant in that sense; if I, and I alone, deserted, the loss would be infinitesimal. The catch is, I could never know that I was acting alone.

And the truth is, versions of me probably have deserted; however stable my personality, it’s hard to believe that there are no valid quantum permutations entailing such an action. Whatever the physically possible choices are, my alter egos have made—and will continue to make—every single one of them. My stability lies in the distribution, and the relative density, of all these branches—in the shape of a static, pre-ordained structure. Free will is a rationalisation; I can’t help making all the right decisions. And all the wrong ones.

But I ‘prefer’ (granting meaning to the word) not to think this way too often. The only sane approach is to think of myself as one free agent of many, and to ‘strive’ for coherence; to ignore short cuts, to stick to procedure, to ‘do everything I can’ to concentrate my presence.

As for worrying about those alter egos who desert, or fail, or die, there’s a simple solution: I disown them. It’s up to me to define my identity any way I like. I may be forced to accept my multiplicity, but the borders are mine to draw. ‘I’ am those who survive, and succeed. The rest are someone else.

I reach a suitable vantage point and take a third count. The view is starting to look like a half-hour video recording edited down to five minutes—except that the whole scene doesn’t change at once; apart from some highly correlated couples, different people vanish and appear independently, suffering their own individual jump cuts. They’re still all shifting universes more or less together, but what that means, in terms of where they happen to be physically located at any instant, is so complex that it might as well be random. A few people don’t vanish at all; one man loiters consistently on the same street corner—although his haircut changes, radically, at least five times.