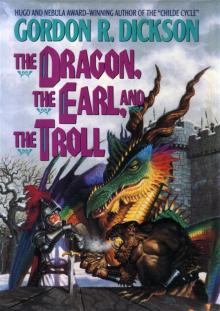

The Dragon, the Earl ,and the Troll

Gordon R. Dickson

The Dragon, The Earl,

and The Troll

Gordon R. Dickson

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Epilogue

Chapter 1

The Hobgoblin had come out into the kitchen again. "I can't understand it!" Jim said. "Fleas, lice, rats, hedgehogs looking for a warm place to sleep—but hobgoblins!"

"Calm down," said Angie.

"Why do we have to have hobgoblins?" demanded Jim.

All hobgoblins lived in chimneys. They were small, harmless, sometimes beneficial Naturals. You left out a bowl of milk—or whatever you had to share with them—every night.

The Hobgoblin would drink or eat that, and not bother anything else. But the Malencontri kitchen Hobgoblin apparently went on periodic binges. He did not drink anything, unless it was milk; but when on a binge he took one bite only out of everything else that was eatable in the kitchen—and after that the kitchen workers would not touch anything he might have touched, for some superstitious reason.

"Calm down—" said Angie…

"—Remember?" said Angie now. "And that was just the day before yesterday."

She nestled a little closer with her head in the hollow of Jim's shoulder as they stood together, the only people awake and on their feet along the wooden walkway just behind the top of the curtain wall—that later centuries would rush to call "the battlements" of a castle—of their home, Malencontri.

A December dawn, icy under a cloud-heavy sky, was just breaking. In its gray light they looked out on the trampled open space before the wall, to the thick surround of forest, some hundred yards away, from which a few pencil-thin ghosts of gray smoke were beginning to rise, back a small distance behind the first treetops.

Yesterday's blood had turned black on the snow and become indistinguishable from the blackness of the miry ground, where snow and bare earth had been ground together into equally black mud, under heavy boots and iron heels.

A little snow had fallen during the late afternoon of the attack, and had to a certain extent hidden the dark shapes that lay still on the ground—those of their attackers who had been left to the crows and other scavengers that would follow after Malencontri had been taken. As taken it would be, today.

Its defenders were too few, and now too exhausted. Along the walkway to the right and left of where Jim and Angie stood, worn-out archers, crossbowmen and men-at-arms—those still able to fight in spite of their wounds—had fallen asleep where they had stood to push back the attackers that tried to climb in from scaling ladders on the outside of the curtain wall.

Given sufficient defenders inside her walls, Malencontri could have held off an army, let alone this small force of two or three knights with perhaps a hundred and fifty trained men-at-arms and archers and a couple hundred ragtag and bobtail of the lower classes, armed with whatever they had been able to bring or acquire on their raid into this part of Somerset.

But Malencontri had had no warning—not even time enough to call in the people who belonged to it from the surrounding forest and fields that were part of the fief, who might have swelled their force to the point where the attackers would have no chance.

As it was, the attackers must clearly be in ignorance of the fact that Jim was in the castle. Otherwise they would never have had the courage to attack a fortification owned by any low-ranking magician—let alone one who had the notoriety that Jim had gained as the Dragon Knight.

"They'll be waking up now out there," murmured Angie.

"Yes," said Jim. He, too, had been watching the fingers of smoke from the remnants of the overnight fires of their attackers; watching for an increase in the smoke they sent up, as new fuel was added and some kind of food was cooked or wanned for those who would attack again today.

"At any rate," said Angie, squeezing Jim's waist with the arm she had around it, "this ends all hopes for the baby." She was silent a moment. "Was I really unbearable to you with all my worrying about her?"

"No," Jim said. He kissed her. "You've never been unbearable. You know that."

The baby, as it had come to be referred to, had been Angie's particular concern for the last year or so. She was only in her mid-twenties; but here, history was still in the Middle Ages, and all around her much younger women—girls even—were having children. She had been torn between her desire for a child and her feeling, which she shared with Jim, that it would be unfair to have it here.

Let alone bring it up in this medieval time, which was still in the equivalent of what had been the fourteenth century, in contrast to the twentieth-century version of Earth from which they had come.

So they had simply put off having children. Now, it was too late—which was probably just as well, given the fact that the attackers would kill everything living in the castle, once they had got inside.

"In fact," said Jim, "I should have found a way back for us before this."

"You did once, in the beginning," said Angie. "I talked you out of it."

"No, you didn't."

"Yes, I did."

They were both right, in a sense. For a brief time, after Jim had come here to rescue Angie from the Dark Powers that strove to upset the balance of Chance and History in this medieval version of Earth, Jim had possessed enough magical credit to send them both back to the twentieth century.

Angie had said then that she wanted to do what he wanted to do; and the truth was, he had wanted to stay. They both had—they still would have, if it had not been for the matter of the baby.

But then, neither of them had looked ahead to the fact that they would go on living, go on aging; and that a day like this day might dawn, in which it was practically certain that they both would die—hopefully before they could be captured; because if so they could only look forward to being crucified, impaled or tortured by those who would overrun and pillage their castle; as the attackers could hardly be stopped from doing before the sun set again.

In what the Middle Ages considered a "legal war," Jim and Angie and any children of theirs would have been held to ransom. But not in a raid like this, which was itself "illegal."

Jim looked again at the wisps of smoke. It was impossible to say whether they had started to thicken or darken at all; but the day was definitely brightening, and it could not be long now before those out there would be up and stirring. Some of Malencontri's men-at-arms had recognized some of those who were trying to get into the castle. They were retainers of Sir Peter Carley, a knight formerly in fief to the Earl of Somerset who had come to a parting of the ways with the Earl

and now was in fief to the Earl of Oxford.

Since his violent parting with the Earl, Sir Peter had, in common fourteenth-century fashion, regarded all those in Somerset as legitimate prey; and he had used the recent march of a mob of peasants in revolt to London as an excuse to raid into the Somerset area—and it was this that had brought him to Malencontri.

"I hate to rouse them," said Angie, looking at the archers and men-at-arms that lay huddled against the inner stonework of the wall, curled up to conserve as much body heat as possible while they slept. "I don't know why most of them haven't simply frozen there, lying in the open like this."

"Some may," said Jim.

"Maybe it'll be easier on them, that way," said Angie. "I can't believe that none of our messengers got through. We had so many friends…"

Indeed, they had many friends. It was one of the things that caused them to be attached to this fourteenth century, in spite of its hobgoblins, hedgehogs, rats, fleas, lice… Naturals, magicians, sorcerers, Dark Powers—and everything else that made life here either interesting or perilous.

In fact, some of those they knew were almost more than good friends—incredibly loyal, trustworthy, back-you-up-and-come-to-your-rescue-at-any-time-without-question sort of friends. The mysterious thing was that none of these had come to help them this time.

It was true, Jim thought, that the messengers to these friends for help had been sent out, literally, within minutes after their attackers had been discovered less than half a mile from the castle. It was possible that all the messengers had been captured by those now trying to take Malencontri; and at this moment they were all very dead. But some should have got through.

True, both Dafydd ap Hywel and Giles o'the Wold were far enough off so that they might have not heard from the messenger and been able to get back here, in the two days since the attackers had first arrived.

But Sir Brian Neville-Smythe's castle—Castle Smythe—was less than a fifteen-minute gallop from Malencontri; and Malvern Castle, the fortress of which the Lady Geronde Isabel de Chaney was Chatelaine—she to whom Sir Brian was betrothed—was not an impossible distance off, Sir Brian should have come, and Geronde have sent fighting men to their rescue, if messengers had been able to reach them safely. But no assistance from either one had shown up.

Most curious of all was the nonappearance of Aargh the English wolf, who invariably knew everything that was happening in the land for miles around. Aargh might have been expected to show up on his own initiative; certainly he would have done so if he had known what was going on. He had come to join them in their beleaguered castle, earlier this same year, running literally over the backs of hundreds of closely packed sea serpents to do so, and needing to be hauled up from the moat with his teeth clenched in a rope dropped from the curtain wall to him.

For that matter, the failure of Carolinus to show up was also mysterious. True, Jim had foolishly overspent his magic reserve—this time in what even Angie would consider a good cause (but Carolinus would not)—helping to get the harvest in, this fall, and the castle prepared for winter.

But none of them had appeared.

"Most likely, the messengers didn't get through," said Jim, avoiding the fact that Angie would know as well as he that neither Aargh nor Carolinus should have needed to be summoned. They should have known when Malencontri was under attack; and then both would have come out of friendship—though neither of them would admit to such a weakness; and Carolinus additionally would have appeared out of a sense of responsibility to his apprentice in magic, which Jim happened to be.

"It doesn't matter," murmured Angie into Jim's chest.

"GREETINGS!" boomed an enormous voice.

Jim and Angie looked up, startled, to see a giant—a real giant, thirty feet if he was an inch—approaching the curtain wall from the woods with twenty-foot strides.

Chapter 2

Rrrnlf!" said Angie. It was indeed the sea devil, whom they had met earlier in the year when the sea serpents had attempted an invasion of England in collaboration with the French. The most unlikely of rescuers—if he was indeed that.

Jim's gaze flew to the smoke streams above the treetops. Rrrnlf was advancing from an area of the surrounding trees not at all far from where the smoke streamers had been ascending. Now, Jim saw they were still there, but they were certainly no thicker or darker—implying the fires underneath them had not been refueled—and in fact if anything they were more thin and ghostlike than ever, as if those same fires were dying out.

Jim looked quickly back at the sea devil. Rrrnlf was almost to the curtain wall now and seeming to loom above them already.

Rrrnlf was not only a Natural, but one of the largest inhabitants of this world's oceans; though he also was apparently quite comfortable not only in fresh water but in the open air as he was now. However, aside from his thirty feet of height, his body had a strange construction.

Essentially, he was wedge-shaped, the point of the wedge being downward. He literally tapered from the top of his head to the soles of his feet. His head was large even for the rest of him. His shoulders were somewhat smaller than they should have been, according to human proportions, but only a little. However, below those shoulders not only did his body taper toward the waist, but his arms narrowed down toward his hands—though not excessively, for his hands were as large as the shovel ends of a derrick. But from his waist he continued tapering down to feet that were only several times as large as Jim's. It was remarkable how those relatively tiny feet bore the weight of the rest of him about so briskly and without complaint. But of course, like all Naturals, there was a touch of innate magic in him; though, again like all Naturals, he had no real control over it.

He had reached the wall now. He put one massive hand on the top of it and vaulted over its twenty-foot height, landing on his feet in the courtyard. The wall shook, waking up all the sleepers along it, while the impact of his massive weight on the packed earth of the courtyard probably produced enough sound to wake up most of the rest of those exhaustedly slumbering inside the castle buildings.

"Thu ne grete—" he began, slipping into the Anglo-Saxon speech of a thousand years before. He checked. "I mean—you didn't say greetings to me!" he accused, looking down on them, with a reproachful frown from his heavy-boned, blue-eyed face, some dozen feet above them as they stood on the walkway.

"Greetings!" said Jim and Angie hastily and simultaneously.

Rrrnlf's visage cleared. It became a rather simple, friendly face, with nothing really terrifying about it except its size.

"My mother always told me this was the season for greetings amongst you wee folk," he rumbled, "or have I lost track of time and customs changed since I was here last?"

"No, Rrrnlf," said Angie, "you were here only five months or so ago."

"So I was!" said Rrrnlf. "I didn't think it had been too long. I've just had time to find some gifts for you. My mother—did I ever tell you about my mother?"

"Yes," said Jim, "you did."

"I had a beautiful mother," said Rrrnlf almost dreamily, paying no attention at all to what Jim had said. "She was beautiful. I can't remember exactly how she looked; but I remember she was beautiful. She took care of me for the first four or five hundred years while I was growing up. There never was a mother like that. Anyway, she told me lots of things; and one of them was that around this time of the year when the deep-sea currents change, you wee people greet each other and some of you give others gifts. Because you helped me so much in getting back my Lady, I wanted to be sure I gave you gifts this year. I had some trouble finding them, but I've got some."

Rrrnlf's Lady, Jim had discovered earlier, had been the demountable figurehead of a ship, like the dragon figureheads that the Vikings took down from their long ships when putting in to land; because the land trolls were supposed to feel themselves challenged if the dragon heads were brought into their territory. But in this case, it had been a wooden carving from a sunken ship, intended to represent the ninth wa

ve.

The folk saying was that "the ninth wave always came farthest up the beach," and the Norse people had called the ninth wave Jarnsaxa—'the Iron Sword'.

Jarnsaxa had been the daughter of Aegir, the Norse sea god, and Ran, the giantess. Those two had been the parents of all nine daughters who were the nine waves. Last and greatest of these was Jarnsaxa; and Rrrnlf had claimed that—wild as it sounded—he and the actual Jarnsaxa had been lovers. But he had lost her, when Aegir and Ran left with the other Norse gods and giants, taking their daughters with them.

So he had valued the figurehead very highly. But it had been stolen from him as part of the events leading to the attack of the sea serpents on England.

Jim had managed to rouse Carolinus—one of only three AAA+ magicians in this world—from a deep depression just in time to defeat the giant, deep-sea squid who was the mastermind behind the serpents; and so regain the figurehead for Rrrnlf.

"So, here they are, now," said Rrrnlf, dipping a massive hand into the pouch that hung from what looked like a small cable around his relatively narrow waist, tied over the skin—or whatever it was—he wore, wrapped caveman-fashion, around him and hanging from one shoulder, to end in a sort of kiltlike lower edge just above his knees.

The hand enclosed and hid what he first brought up, and he extended that massive fist toward Angie, who unconsciously took half a step backward from it.

"Here you are!" said Rrrnlf, apparently not noticing the fact that Angie had recoiled. "This is for you, wee Lady. Hold out your hands."

Angie held out both hands cupped together, and very carefully Rrrnlf gradually opened his enormous fist, shook it a little—and something that seemed to be an assortment of tied-together small objects, glinting red in the clouded early daylight, dropped into Angie's hands, half filling them.

Angie gasped.

Jim stared.

What Angie held appeared to be some sort of necklace, with several strands all connected to a single strand that possibly was meant to tie or fasten behind the neck. Ornamenting each strand were what seemed to be—but what it was hard to believe could be, large as they were—enormous rubies. They had not been cut and faceted, as twentieth-century cut gems would have been; but they had been polished, and they shone with beautiful warmth against the gray day and the background of wintry trees, stone, snow and trampled earth.