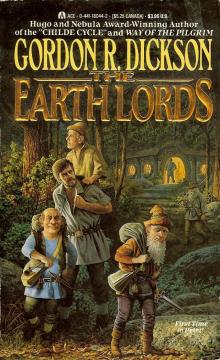

The Earth Lords

Gordon R. Dickson

SOME CALL IT HELL…

A hidden labyrinth beneath the Canadian wilderness, where dwarfish Lords and Ladies ride humans like horses—and plot the final downfall of mankind.

Bart Dybig is a “Steed,” but one gifted with mental and physical abilities unsuspected by those who have enslaved him. Soon, he vows, he will surprise the Lords and escape to the world above…

If there’s a world left to go back to.

This book is an Ace original

edition, and has never been previously published.

THE EARTH LORDS

An Ace Book/published by arrangement with

the author

PRINTING HISTORY

Ace edition/January 1989

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1989 by Gordon R. Dickson.

Cover art by Keith Parkinson.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part,

by mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For information address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016.

ISBN: 0-441-18044-2

Ace Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016.

The name “ACE” and the “A” logo are

trademarks belonging to Charter Communications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO PAT OANES,

who appeared in our lives just in time

to rescue both my mother and myself.

Acknowledgments

I want to express my appreciation in particular to David Wixon and Sandra Miesel, whose research and work in a large number of different areas helped make this book possible; as well as to a number of other experts in various fields to whom I turned for help and was given it.

chapter

one

IT WAS EARLY spring yet, this high up, and the pony came gratefully to the top of the little hill. Bart Dybig stopped to let the beast catch its breath, while he looked over the tiny settlement in the river valley below before riding down into it. He was too heavy for the pony, that was the truth of it; though so compact was the bone and muscle of his solid body that most people would have guessed him thirty or more pounds less than his real weight.

Now that he was here, he found himself of two minds about riding down into that place. The whole reason for his coming this long distance was to do so. At the same time the habit of being by himself had brought him almost to the point of avoiding society completely. He had a strange feeling of uneasiness about what riding down the hill into the settlement before him might lead him into.

But there was nothing in what he saw to justify such a feeling.

The settlement itself was ordinary-looking enough. Some eight buildings were strung out on either side of a single street, a small distance back from the thin blue line of the small river that had its home in this valley. All the buildings were of logs; and only one, in the center of the settlement on the far side of the street from Bart’s point of view, had anything resembling an actual second story. It also had a couple of fairly good-sized windows fronting the street, and an open porch—accumulation of luxuries on this west Canadian frontier in 1879—that strongly suggested that the front part of the building, at least, was more store than living quarters.

He rode the pony at a walk down the hill toward the settlement.

The closer he got, the more the place rang a note of warning in a part of his mind that the time with Louis Riel had honed to constant awareness of possible danger. Since leaving Louis in his exile in the United States and returning to Canada, he had been passed on westward from group to group of métis—those people who were the result of the interbreeding of the early European furtrappers and the native Indians. Bart’s father had been European —even if other men, Indian, white and mixed-breed alike, had combined in avoiding him—and Bart’s mother had been a Cree Indian whose name in English translated to “Listens to Trees.”

Both of his parents were dead now’—Bart’s mother by a raging fever when he was six years old, and his father, in Montana, in the United States, by a rifle bullet from a distant assassin—a bullet clearly intended for Riel, as the two men rode side by side. Riel had escaped below the border, after the métis had risen for their rights and had their uprising put down by soldiers from eastern Canada; and Bart’s father, with Bart, had gone with the métis leader.

His father had been a close adviser to Riel, who alone besides Bart had come to understand the innate gentleness in the physically powerful and brilliant, but misshapen little man. When his father had died, after nearly a week of fever from an infection brought on by the bullet, which had lodged too deep in the older man’s body to be removed, Bart had considered himself released of any further duty to Riel. After working a few years to raise money that would set him free to travel, Bart had returned to Canada in search of a relative he had never known he had until the delirium of his father’s dying hours.

All that Bart had been able to gather, putting together the fragments of his father’s brief, fevered utterances, was that the relative was a woman and named, or called, “Didi,” and that she was to be found somewhere in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, most probably somewhere on the western side of that range.

The métis who had remained in Canada had aided Bart and passed him on from group to group. His clothing, the brown Indian eyes which he had inherited from his Cree mother, his very way of walking and riding, was his passport among them. He was métis himself, and looked it. In their small settlements he had felt, momentarily at least, at home and for the moment safe, although there was a price, if a small one, on his head from the days of the rebellion.

But he did not feel at home or safe as he rode down into this settlement marked on the map in his saddlebags as Mossby. The blind but always to be listened to instinct within him was sounding a signal.

Unobtrusively, he loosened his rifle in its saddle scabbard and checked the heavy revolver in the holster at his belt, hidden under his leather jacket. For the first time it struck him what was bothering him about the group of houses before him. There were no children to be seen about, nor any dogs.

True, there were no adults to be seen, either; but at this time of the spring afternoon they could be up and out, away from home, or inside the buildings, out of sight. He headed toward the large building that he had assumed to be a store, though this place was beyond the very end of the high western plains, in the beginnings of the Rocky Mountains. Any goods that came in here for store sale would necessarily have come by pack horse. There was a hitching rail before the store building, but no horses at it.

It was the more surprising, in light of the quietness of the place and his own feeling of inner warning, that just as he rode up to the hitching rail a man he recognized came out of the front door of the store—and the feeling of fate chimed loudly within him.

“Arthur!” said Bart.

The other turned and stared, still holding the bale of furs he had brought out. Slowly, he put the bale down on the floor of the porch, against the log wall, and stared at Bart, clearly without recognition.

The lack of recognition, at least, was. not so surprising.

Now in his twenty-fifth year, Bart had changed from the barely adult young man Arthur Robeson had last seen in the town of Sainte Anne, far to the east on the central plains, where they had grown up together. For one thing, Bart had come into his full weight and strength—that strength he had inherited from his father, but in as far greater measure as his larger body had outstripped the older man’s small one.

With that development had come a squareness, a blocklike app

earance that made other men walk around him unthinkingly. These things had come with the years of the 1870s. Now, in 1879, that growth had hardened on him. He stood five feet eleven inches in his stocking feet, which was tall compared to the average of the people around him; but there was no lack of men taller—and bigger—than he was.

The difference that set him apart from everyone else was not in his height, but in the unusual development of his body. His shoulders, as his father’s had been, we-e almost unnaturally square and wide, and his chest was massive; but the real difference in him was his legs, disproportionately thick though now hidden by the wide leather trousers. The power of those legs had even surprised him, at times. At eighteen he had lifted horses, quite easily, on his shoulders until their hooves cleared the ground. He had done this to win bets and to show off, on several occasions—until he found that advertising his strength this way only seemed to increase the isolation which both he and his father had always seemed to feel from the world in general around them. Once he had realized this, he had stopped showing off. In fact, he had ended by sidestepping situations in which his strength might be noticed at all.

So it was not surprising then that the slim, white-skinned, brown-haired Scotsman who had known him as a boy did not recognize this thick-bodied stranger in the leather shirt, trousers and jacket. This armed stranger with the large head in which the heavy bones of brow and cheeks were prominent under the black hair and the tanned skin, and the face below the cheekbones hidden by the full, bushy, black beard Bart had grown to disguise himself when he slipped back across the border from the U.S.

For a moment Bart felt again the empty sense of isolation. Then he reminded himself that they had never been close anyway; and it did not matter about Arthur. What mattered—and he felt a sudden leap of joy within him—was that if Arthur were here, it was more than possible that Arthur’s sister Emma was also here—even possible she was still unmarried. Emma, with whom Bart had fallen in love as a boy in school—those few years of school before the tide of the rebellion claimed him, young as he was. It might, in fact, have been Emma’s liking for him that fed Arthur’s dislike; for Arthur, although he showed little affection for his sister, had always wanted all of her attention. Their family had been storekeepers even then, back in Sainte Anne; and their mother, particularly, had always thought of their family as better than the métis around them.

But suddenly Bart was ashamed of himself for remembering Arthur so unkindly. If the other was willing to let bygones be bygones, now that they were all grown up, he could be willing also to start over from scratch in their acquaintanceship.

“Don’t you know me, Arthur?” Bart said accordingly, halting his horse by the hitching rail, dropping its reins over the wooden bar and looking up at the other man, who stood on the porch above him. “I’m Bart Dybig.”

“Bart?” Arthur still stared at him, but now as if trying to see I through the beard to the boy he had known. “What are you doing here? The last I heard you’d gone to Montana with Riel.”

“I’m looking for someone I heard was here—Telesphore Daudet. You know him?”

“Yes,” said Arthur, his face still uneasy. “He lives here. Or at least he did—his squaw still does. But he went hunting, off into the mountains, some weeks ago, and he’s never come back. Something may have happened to him out there.”

Bart frowned. Telesphore Daudet, he had been told at the last settlement of métis he had visited, had been the man who could direct him on into the mountains, to where his father had, in his ravings, mentioned that some relatives of theirs lived.

The name of Telesphore Daudet was all Bart had to go on; such clues as Bart had been able to glean from his father’s dying words had been vague, and it required the right man to be able to listen to such words and suggest the place they might refer to. The last such man, far east of here, had said Daudet might be a man to talk to, and he had tracked that name here to Mossby.

“You knew him?” Arthur asked, from up on the porch.

“No,” answered Bart cautiously, “I was just dropping by with a message from an old friend of his. ” He put the problem of Daudet from his mind for the moment.

“Have you been here yourself, long?” he asked Arthur. “What about Emma? Is she still with you?”

“About five years,” said Arthur.

“And Emma?”

“Yes.” The word came out of Arthur slowly and reluctantly. Evidently Arthur was still possessive of his sister.

“Then she’d be inside there?” said Bart, nodding at the store. “I’ll just step in and say hello to her. It’ll be good to see her, too.”

Arthur took a short step toward the front door, almost as if he would move between it and Bart. But Bart was coming up the steps, moving with all the casual but unstoppable progress of a boulder rolling downhill; and at the last moment Arthur turned and opened the door for him.

“I think she’s probably up to her ears in work in the back,” Arthur said. “It might be better not to disturb her now.”

“Come on now, Arthur,” said Bart, continuing past the other man into the interior, “she won’t mind a moment or two, after all these years. . . .”

Within, the front lower half of the house had been partitioned off and fitted with counters and shelves to hold the goods of the store. So, thought Bart, he had been right. The air was strong with the aromas of pelts, woolen goods, liquid parafin—that fuel for lamps some people were beginning to call “kerosene”—and several dozen other odors. In appearance, it was no different from any of the small settlement stores Bart had been stepping into all his life, not only in the western Canada fur country, but down in Montana territory as well.

Except that behind the main counter at the back of the store, just coming in through a door that must lead to a back room, was a slim, small young woman. She had straight blond hair and blue eyes, in a round face that was not conventionally pretty but had a serene happiness about it that made it, and had always made it, Bart thought, beautiful.

“It’s Bart Dybig, Emma,” said Arthur, quickly and harshly behind Bart.

Emma’s expression of pleasant welcome for a stranger was wiped out by one of happy recognition.

“Bart!” she cried, dropping onto the counter the armful of pelts she was carrying and coming out through an opening in it to grasp both of Bart’s outstretched hands with her own. “And with a beard like that! Oh, it’s good to see you again, Bart!”

He was suddenly warm with happiness. Not merely the happiness that being with her had always kindled in him, but a particular powerful joy that she should be so pleased to see him again. The sense of isolation and loneliness was utterly wiped away.

“It’s wonderful to see you, Emma,” he said.

He had completely forgotten Arthur, the store, everything but the f two of them and their joined hands—when the voice of the other man jolted him out of it.

“Bart’s just passing through, Emma,” said Arthur. “He came by with a message for Telesphore Daudet from a friend of Telesphore’s.”

“And Telesphore’s been gone for weeks!” said Emma without letting go of Bart’s hands. “We’re worried about him. Was he a friend of yours, Bart?”

“No,” said Bart. “I never heard of him until I was asked to drop by here. I didn’t know you two were here.”

“But we’ve been here for five years. Do you realize how long it’s been since we’ve seen each other? You’ll stay with us while you’re here, Bart; and we’ll have a special dinner tonight.”

“There’s no extra room,” said Arthur.

“We can clear the furs off that bunk in the back room, the bunk we always give to the pack-train handlers when they come—what’s wrong with you, Arthur?” said Emma, for the first time taking her eyes off Bart and looking over at her brother.

It had always been Arthur’s habit to bully his sister and order her about; and Emma had almost always let herself be bullied and ordered. But on the few occasions when

Bart had seen her face up to Arthur, he had noticed that it was always Arthur who backed down. It was that way now.

“We’ve got all these furs to sort and get ready before the pack-train comes to take them east,” he muttered, looking away from his sister. “And what’ll we do when the pack-train handler gets here if we’ve somebody already staying in that bunk?”

“He can find a place to stay with someone else in town. Don’t be stupid, Arthur!” said Emma. She let go of Bart’s hands and reached up to her hair. “I’m covered with dirt and dust. We’ve been cleaning out the back room, as Arthur says—getting the winter pelts ready to send off to market.”

“Tell me what I can do,” said Bart.

His words were automatic. Anyone, even a complete stranger, was always offered food and shelter. And any such stranger always turned to immediately to help his hosts with whatever chores or other work had them busy at the moment.

“You can help me sort the furs that’re left. Arthur grades well, but sometimes I’m a little faster at it than he is. And Arthur can bale the sorted furs, while you carry them out to the porch ready for the pack-train to pick up.”

“I’ll help you sort,” said Arthur. “Bart can carry them out.” It was a small meanness, to deprive the two of them of being together during what remained of the afternoon; but Bart did not greatly mind. Just to be under the same roof with Emma had always seemed to bring happiness to him. Also, the prepared and tied bales were heavy. Arthur had made a load of just one as Bart was riding up. But Bart himself could have carried four of them without thinking. He reminded himself to take them one at a time, like Arthur, to give the other as little reason for annoyance as possible.

The two men followed her back into the storeroom. This room at the moment was a place of dark and dusty comers, glaringly lit at its center by the white-hot, glowing mantles of two parafin lamps set on flour barrels. The air, too, was full of dust and hair from the fur of the pelts; and boxes of goods were stacked everywhere.