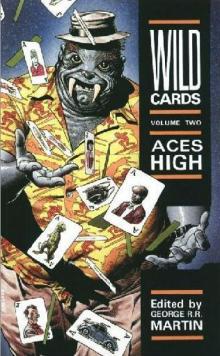

Aces High wc-2

George R. R. Martin

Aces High

( Wild Cards - 2 )

George R R Martin

George R R Martin

Aces High

1979

PENNIES FROM HELL

By Lewis Shiner

There were maybe a dozen of them. Fortunato couldn't be sure exactly because they kept moving, trying to circle behind him. Two or three had knives, the rest had sawed-off pool cues, car antennas, anything that would hurt. They were hard to tell apart. Jeans, black leather jackets, long, slicked-back hair. At least three of them matched the vague description Chrysalis had given him.

"I'm looking for somebody called Gizmo," Fortunato said. They wanted to herd him away from the bridge, but they didn't want to physically push him yet. To his left the brick path led uphill into the Cloisters. The entire park was empty, had been empty for two weeks now, since the gangs had moved in.

"Hey, Gizmo," one of them said. "What do you say to the man?"

That one, with the thin lips and bloodshot eyes. Fortunato locked eyes with the kid nearest to him. "Take off," Fortunato said. The kid backed away, uncertain. Fortunato looked at the next one. "You too. Get out of here." This one was weaker; he turned and ran.

That was all he had time for. A pool cue came slicing for his head. Fortunato slowed time and took the cue, used it to knock away the nearest knife. He breathed in and things sped up again.

Now they were all getting nervous. "Go," he said, and three more ran, including the one called Gizmo. He sprinted downhill, toward the 193rd Street entrance. Fortunato threw the pool cue at another switchblade and ran after him.

They were running downhill. Fortunato felt himself getting tired, and let out a burst of energy that lifted him off the path and sent him sailing through the air. The kid fell under him and rolled, headfirst. Something crunched in the kid's spine and both his legs jerked at once. Then he was dead.

"Christ," Fortunato breathed, brushing dead October leaves from his clothes. The cops had doubled patrols around the park, though they were afraid to come in. They'd tried it once, and it had cost them two men to chase the kids away. The next day the kids were back again. But there were cops watching, and for something like this they'd be willing to run in and pick up a body.

He dumped the kid's pockets, and there it was-a copper coin the size of a fifty-cent piece, red as drying blood. For ten years he'd had Chrysalis and a few others watching for them, and last night she'd seen the kid drop one at the Crystal Palace.

There was no wallet, nothing else that had any meaning. Fortunato palmed the coin and sprinted for the subway entrance.

"Yes, I remember this," Hiram said, picking the coin up with a corner of his napkin. "It's been a while."

"It was 1969," Fortunato said. "Ten years ago." Hiram nodded and cleared his throat. Fortunato didn't need magic to know that the fat man was uncomfortable. Fortunato's open black shirt and leather jacket weren't really up to the dress code here. Aces High looked out over the city from the observation deck of the Empire State Building, and the prices were as steep as the view.

Then there was the fact that he'd brought along his latest acquisition, a dark blonde named Caroline who went for five hundred a night. She was small, not quite delicate, with a childlike face and a body that invited speculation. She wore skintight jeans and a pink silk blouse with a couple of extra buttons undone. Whenever she moved, so did Hiram. She seemed to enjoy' watching him sweat.

"The thing is, that's not the coin I showed you before. It's another one."

"Remarkable. It's hard to believe that you could come across two of them in this good a condition."

" I think you could put that a little stronger. That coin came of a kid from one of those gangs that's been trashing the Cloisters. He was carrying it loose in his pocket. The first one came of a kid that was messing with the occult."

It was still hard for him to talk about. The kid had murdered three of Fortunato's geishas, cut them up in a pentagram for some twisted reason that he still hadn't figured out. He'd gone on with his life, training his women, learning about the Tantric power the wild card virus had given him, but otherwise keeping to himself.

And, when it got to bothering him, he would spend a day or a week following one of the loose ends the killer had left behind. The coin. The last word he'd said, "TIAMAT" The residual energies from something else that had been in the dead boy's loft, a presence that Fortunato had never been able to trace.

"You're saying there's something supernatural about them," Hiram said. His eyes shifted to watch Caroline as she stretched languorously in her chair.

"I just want you to take another look."

"Well," Hiram said. Around them the luncheon crowd made small noises with their forks and glasses and talked so quietly they sounded like distant water. "As I'm sure I said before, it appears to be a mint 1794 American penny, stamped from a hand-cut die. They could have been stolen from a museum or a coin shop or a private…" His voice trailed of. "Mmmmm. Have a look at this."

He held the coin out and pointed with a fleshy little finger, not quite touching the surface. "See the bottom of this wreath, here? It should be a bow. But instead it's something sort of shapeless and awful looking."

Fortunato stared at the coin and for a half-second felt like he was falling. The leaves of the wreath turned into tentacles, the ends of the ribbon opened like a beak, the loops of the bow became shapeless flesh, full of too many eyes. Fortunato had seen it before, in a book on Sumerian mythology. The caption underneath had read

"TIAMAT".

"You all right?" Caroline asked.

"I'll be okay. Go on," he said to Hiram.

"My instinct would be to say they're forgeries. But who would forge a penny? And why not take the trouble to age them, at least a little? They look like they'd been stamped out yesterday."

"They weren't, if that matters. The auras of both of them show a lot of use. I'd say they were at least a hundred years old, probably closer to two hundred."

Hiram pushed the ends of his fingers together. "All I can do is send you to somebody who might be more help. Her name is Eileen Carter. She runs a small museum out on Long Island. We used to, um, correspond. Numismatics, you know. She's written a couple of books on occult history, local stuff." He wrote an address in a little notebook and tore out the page.

Fortunato took the paper and stood up. "I appreciate it."

"Listen, do you think…" He licked his lips. "Do you think it would be safe for a regular person to own one of those?"

"Like, say, a collector?" Caroline asked.

Hiram looked down. "When you're finished with them. I'd pay."

"When this is over," Fortunato said, "if we're all still around, you're welcome to them."

Eileen Carter was in her late thirties, with flecks of gray in her brown hair. She looked up at Fortunato through squaredoff glasses, then glanced over at Caroline. She smiled.

Fortunato spent most of his time with women. Even as beautiful as she was, Caroline was insecure, jealous, prone to irrational dieting or makeup. Eileen was something different.

She seemed no more than a little amused by Caroline's looks. And as for Fortunato-a half-Japanese black man in leather, his forehead swollen courtesy of the wild card virus-she didn't seem to find anything unusual about him at all.

"Have you got the coin with you?" she asked. She looked right into his eyes when she talked to him. He was tired of women who looked like models. This one had a crooked nose, freckles, and about a dozen extra pounds. Most of all he liked her eyes. They were incandescent green and had smile lines in the corners.

He put the penny on the counter, tails up.

She bent over to look at it, touching the bridge of her glasses with one finger. Sh

e was wearing a green flannel shirt; the freckles ran down as far as Fortunato could see. Her hair smelled clean and sweet:

"Can I ask where you got this?"

"It's kind of a long story," Fortunato said. "I'm a friend of Hiram Worchester. He'll vouch for me if that'll help."

"It's good enough. What do you want to know?"

"Hiram said it was maybe a forgery."

"Just a second." She took a book off the wall behind her. She moved in sudden bursts of energy, giving herself completely to whatever she was doing. She opened the book on the counter and flipped through the pages. "Here," she said. She studied the back of the coin intently for a few seconds, biting on her lower lip. Her lips were small and strong and mobile. He found himself wondering what it would be like to kiss her.

"That one," she said. "Yes, it's a forgery. It's called a Balsam penny. Named after `Black John' Balsam, it says. He minted them up in the Catskills around the turn of the nineteenth century." She looked up at Fortunato. "The name rings a bell, but I can't say why."

"`Black John'?"

She shrugged, smiled again. "Can I hang on to this? Just for a few days? I might be able to find something else for you."

"All right." Fortunato could hear the ocean from where they were and it made things seem a little less dire. He gave her his business card, the one with just his name and phone number on it. On their way out she smiled and waved at Caroline, but Caroline acted like she didn't see it.

On the train back to the city Caroline said, "You want to fuck her, don't you?"

Fortunato smiled and didn't answer her.

"I swear to God," she said. Fortunato could hear Houston in her voice again. It was the first time in weeks. "An overweight, broken-down old schoolmarm."

He knew better than to say anything. He was overreacting, he knew. Part of it was probably just pheromones, some kind of sexual chemistry that he'd understood a long time before he learned the scientific basis for it. But he'd felt comfortable with her, something that hadn't happened very often since the wild card had changed him. She'd seemed to have no self-consciousness at all.

Stop it, he thought. You're acting like a teenager. Caroline, under control again, put a hand on his thigh. "When we get home," she said, "I'm going to fuck her right out of your mind."

"Fortunato?"

He switched the phone to his left hand and looked at the clock. Nine A.M. "Uh huh."

"This is Eileen Carter. You left a coin with me last week?" He sat up, suddenly awake. Caroline turned over and buried her head under a pillow. "I haven't forgotten. How are you doing?"

"I may be on to something. How would you feel about a trip to the country?"

She picked him up in her VW Rabbit and they drove to Shandaken, a small town in the Catskills. He'd dressed as simply as he could, Levi's and a dark shirt and an old sportcoat. But he couldn't hide his ancestry or the mark the virus had left on him.

They parked in an asphalt lot in front of a white clapboard church. They were barely out of the car before the church door opened and an old woman came out. She wore a cheap navy double-knit pantsuit and a scarf over her head. She looked Fortunato up and down for a while, but finally stuck out her hand. "Amy Fairborn. You would be the people from the city."

Eileen finished the introductions and the old woman nodded. "The grave's over here," she said.

The stone was a plain marble rectangle, outside the churchyard's white picket fence and well away from the other graves. The inscription read, "John Joseph Balsam. Died 1809. May He Burn In Hell."

The wind snapped at Fortunato's coat and blew faint traces of Eileen's perfume at him. "It's a hell of a story," Amy Fairborn said. "Nobody knows anymore how much of it's true. Balsam was supposed to be a witch of some sort, lived up in the hills. First anybody heard of him was in the 1790s. Nobody knows where he came from, other than Europe somewhere. Same old story. Foreigner, lives off to himself, gets blamed for everything. Cows give sour milk or somebody has a miscarriage, they make it his fault."

Fortunato nodded. He felt like a foreigner himself, at the moment. He couldn't see anything but trees and mountains anywhere he looked, except off to the right where the church held the top of the hill like a fort. He felt exposed, vulnerable. Nature was something that should have a city around it. "One day the sheriff's daughter over to Kingston came up missing," Fairborn said. "That would be the beginning of August, 1809. Lammastide. They broke in Balsam's house and found the girl stretched out naked on an altar." The woman showed her teeth. "That's what the story says. Balsam was got up in some kind of weird outfit and a mask. Had a knife the size of your arm. Sure as hell he was going to carve her up."

"What kind of outfit?" Fortunato asked.

"Monk's robes. And a dog mask, they say. Well, you can guess the rest. They strung him up, burnt the house, salted the ground, knocked trees over in the road that led up there."

Fortunato took out one of the pennies; Eileen still had the other one. "This is supposed to be called a Balsam penny. Does that mean anything to you?"

"I got three or four more like it at the house. They wash up out of his grave every now and again. `What goes down must come up,' my husband used to say. He buried a good many of these folks."

"They put the pennies in his grave?" Fortunato asked. "All they could find. When they fired the house they turned up a keg of 'em in the root cellar. You see how red it looks? Supposed to be from a high iron content or some such. Folks at the time said he put human blood in the copper. Anyways, the coins disappeared out of the sheriff's office. Most people thought Balsam's wife and kid made off with 'em."

"He had a family?" Eileen asked.

"Nobody saw too much of either of 'em, but yeah, he had a wife and a little boy. Lit off for the big city after the hanging, at least as far as anybody knows."

As they drove back through the Catskills he got Eileen to talk a little about herself. She'd been born in Manhattan, gotten a BFA from Columbia in the late sixties, dabbled in political activism and social work and come out of it with the usual complaints. "The system never changed fast enough for me. I just sort of escaped into history. You know? When you read history you can see how it all comes out."

"Why occult history?"

"I don't believe in it, if that's what you mean. You're laughing. Why are you laughing at me?"

"In a minute. Go on."

"It's a challenge, that's all. Regular historians don't take it seriously. It's wide open, there's so much fascinating stuff that's never been properly documented. The Hashishin, the Qabalah, David Home, Crowley." She looked over at him. "Come on. Let me in on the joke."

"You never asked about me. Which was nice. But you have to know that I have the virus. The wild card."

"Yes."

"It gave me a lot of power. Astral projection, telepathy, heightened awareness. But the only way I can direct it, make it work, is through Tantric magic. It has something to do with energizing the spine "

"Kundalini."

"Yes."

"You're talking about real Tantric magic. Intromission. Menstrual blood. The whole bit."

"That's right. That's the wild card part of it."

"There's more?"

"There's what I do for a living. I'm a procurer. A pimp. I run a string of call girls that go for as much as a thousand dollars a night. Have I got you nervous yet?"

"No. Maybe a little." She gave him another sideways glance. "This is probably a stupid thing to say. You don't fit my image of a pimp."

"I don't much like the name. But I don't run away from it either. My women aren't just hookers. My mother was Japanese and she trains them as geishas. A lot of them have PhDs. None of them are junkies and when they're tired of the Life they move into some other part of the organization."

"You make it sound very moral."

She was ready to disapprove, but Fortunato wouldn't let himself back away. "No," he said. "You've read Crowley. He had no use for ordinary morality, and neither do I. 'Do what

thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.' The more I learn, the more I realize that everything is there, in that one phrase. Its as much a threat as a promise."

"Why are you telling me this?"

"Because I like you and I'm attracted to you and that's not necessarily a good thing for you. I don't want you to get hurt." She put both hands on the wheel and watched the road. "I can take care of myself," she said.

You should have kept your mouth shut, he told himself, but he knew that wasn't true. Better to drive her of now, before he got any more involved.

A few minutes later she broke the silence. "I don't know whether I should tell you this or not. I took that coin around to a couple of places. Occult bookstores, magic shops, that sort of thing. Just to see what I could turn up. I met a guy named Clarke at the Miskatonic Bookstore. He seemed really interested."

"What'd you tell him?"

"I said it was my father's. I said I was curious about it. He started asking me questions like was I interested in the occult, had I ever had any paranormal experiences, that kind of thing. It was pretty easy to feed him what he wanted to hear."

"And?"

"And he wants me to meet some people." A few seconds later she said, "You've gone quiet on me again."

"I don't think you should go. This stuff is dangerous. Maybe you don't believe in the occult. The thing is, the wild card changed everything. People's fantasies and beliefs can turn real now. And they can hurt you. Kill you."

She shook her head. "It's always the same story. But never any proof. You can argue with me all the way back to New York City, and it's not going to convince me. Unless I see it with my own eyes, I just can't take it seriously."

"Suit yourself," Fortunato said. He released his astral body and shot ahead of the car. He stood in the roadway and let himself become visible just as the car was on him. Through the windshield he could see Eileen's eyes go wide. Next to her his physical body sat with a mindless stare. Eileen screamed and the brakes howled and he let himself snap back into the car. They were skidding toward the trees and Fortunato reached over to steer them out of it. The car died and rolled onto the shoulder.