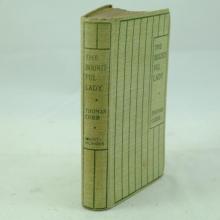

Bountiful Lady

G. A. Henty

Produced by David Edwards, Mary Meehan and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Thisfile was produced from images generously made availableby The Internet Archive)

The Bountiful Lady

--or, How Mary was changed from a very Miserable Little Girl to a very Happy One

BY THOMAS COBB

LONDON: GRANT RICHARDS1900

_CONTENTS_

1. _Mary finds herself in a different place_

2. _Mary sees her Fairy-Godmother_

3. _Mary sees what the Magic Counters can do_

4. _The Story of the Discontented Boy and the Magician_

5. _Mary sees the wings, as well as some other wonderful things_

6. _Mary is taken away_

7. _The Story of the Little Girl, the Dog, and the Doll_

8. _Mary sees something which she has never seen before_

9. _Evangeline gives Mary some Magic Counters_

10. _The Story of the Prince, the Blue-Bird, and the Cage_

11. _Mary sees Mrs. Coppert and Mrs. Coppert sees Mary_

12. _Evangeline says good-bye to Mary Brown_

The Bountiful Lady

I

MARY FINDS HERSELF IN A DIFFERENT PLACE

It was not a dream, this wonderful thing that happened to Mary Brown,although it seemed very much like a dream at first.

Mary was a pretty, round-faced, dirty little girl who had neither afather nor a mother nor a brother nor a sister. Nobody had kissed hersince she could remember, although it was only the day before yesterdaythat Mrs. Coppert had beaten her.

She lived in a poor, narrow street, and during the daytime she spentmany hours in the road. During the night she lay on a sack on the floorof a small room with three other children. Sometimes, when she played inthe road, Mary almost forgot she was hungry; but for the most part, shewas a sorrowful little girl. She had none of the things which you likethe best--she did not even know there were such things in the world; sheseldom had enough to eat, and her clothes were very ragged and dirtyindeed.

One afternoon she was playing in the gutter, it happened to be a littlepast tea-time, although Mary did not always have any tea; she had notoys, but there was plenty of mud, and you can make very interestingthings out of mud if you only know the way. Mary kneeled in the road,with her back to the turning, the soles of a pair of old boots showingbeneath her ragged skirt, as she stooped over the mud, patting it firston one side then on the other, until it began to look something like theshape of a loaf of bread. Mary thought how very nice it would be if onlyit was a loaf of bread, so that she might eat it, when suddenly sheseemed to hear a loud clap of thunder and the day turned into night.

She did not feel any pain, but the street and the mud all disappeared,and Mary Brown knew nothing. For a long time, although she never knewfor how long, she was NOWHERE!

It might have been a month or a week or a day or an hour or even onlyfive minutes or one minute or a second, but when she found herselfSOMEWHERE again it was somewhere else.

Mary had been playing in the road, feeling very hungry, with her handson the soft mud, when this strange sensation came to her and she knewnothing else. And when she opened her eyes again, she was not in theroad any longer, as she would have expected; though for some time yetshe could not imagine where she was or how she had come there.

She was lying on her back, but not upon the floor of the poor house inWilliam Street; she lay on something quite soft and comfortable farabove the boards. All around her she saw an iron rail, and at thecorners two bright yellow knobs. Above, she saw a clean white ceiling,whilst the walls, which were a long way from the bed, seemed to bealmost hidden by coloured pictures.

Instead of her ragged dress, Mary wore a clean, white night-gown, andthere was not a speck of mud on her hands, which astonished her morethan anything else.

'They can't be my hands,' she thought; 'they must belong to somebodyelse. They look quite clean and white, and I am sure I never had whitehands before.'

Then some one came to the bed-side and stood staring down into Mary'sface. She wore a cotton dress and a white cap and apron such as Mary hadnever seen before. She had a pale face, and very kind, dark eyes. Maryliked to watch her when she walked about the room, and presently shebrought a tray covered by a cloth, on which stood a cup and saucer. Shebegan to feed Mary with a spoon, and Mary thought she had never tastedanything so nice before. She felt as if she did not want anything elsein the world--only to know where she was and how she had come here, andwhether she should ever be sent back to Mrs. Coppert and William Street.

But although she wanted to know all this, she did not ask any questionsjust yet, for somehow Mary could not talk as she used to do. But herthoughts grew very busy; she wondered what were the names of thedifferent things she had to eat; she wondered who the tall, dark manwith the long beard could be, who came to see her every morning andlooked at her right foot and felt her left wrist in a strange way. Oneday she raised her head from the pillow to look at the foot herself.

'I see you are better this morning,' said the tall man. 'Do you feelbetter?'

'Quite well, thank you,' answered Mary, and when he went away, Marylooked up at the lady with the kind, dark eyes, and asked, 'What is thematter with my foot, please?'

'Ah! that is to prevent you from running away and leaving us,' was theanswer. 'When we bring little girls here we don't want them to run awayagain.'

'I shouldn't run away,' said Mary solemnly; 'I shouldn't really. I don'twant to run away.'

'That's right.'

'Only where is it?' asked Mary.

'Now don't you think it's a very nice place?'

'Oh, very nice!' cried Mary. 'I know what it is,' she added; 'it's all adream! Only I hope I'm not going to wake again.'

'What nonsense you're talking,' was the answer. 'Of course you areawake, dear.'

'Why do you call me dear?' asked Mary.

'Because I'm very fond of you.'

'But why are you fond of me?' asked Mary. You will notice she ratherliked to ask questions when she got the chance, but they had been veryseldom answered until now.

'Well, now I wonder why!' was the answer. 'Let me see! Haven't I madeyou comfortable and given you nice beef-tea and jelly?'

'I like them very much,' said Mary.

'Well, then, I daresay that's why I like you. Because we generally likepersons if we do kind things for them.'

'I see,' said Mary, but she didn't understand at all. 'But I'm sure it'sa dream,' she added, 'and I do hope I shan't wake!'

'Oh dear!' was the answer. 'Now, do you know what I do to prove littlegirls are awake?'

'No,' said Mary, opening her eyes widely.

'Do you know what pinching is?'

'Oh yes,' said Mary, for Mrs. Coppert was very fond of pinching.

'Well, when I want to prove a little girl is awake, I pinch her.'

'But I know I'm not,' said Mary. 'I can't be. It's all part of thedream--your telling me that.'

Mary began to spoil her dream by looking forward to the time when shemust awake to find herself upon the floor at the house in WilliamStreet, with her ragged dress waiting to be worn again. Still, it wasthe most real dream she had ever had, and it certainly seemed to be avery long one.

But when another week had passed, Mary began to see it was not really adream after all. Everything was just as nice as ever, or even nicer; shehad the most delicious things to eat and drink: chicken and toast, andall sorts of nice puddings, boiled custard, jelly, and grapes andoranges. She was able to sit up in bed to eat them too, and she wore ablue dressing-gown, and the lady with the kind, dark eyes readdelightful stories. Now, this was something

quite new to Mary Brown, andthe stories seemed almost as wonderful as the change in her own littlelife.

She only knew of the things she had seen or heard at William Street--notnice things at all. She had imagined all the world must be like that,for although she was very young, Mary had often thought about things.Still, she had never thought of anything half so wonderful asJack-and-the-Beanstalk, or Ali Baba, or Aladdin, or Cinderella. Marygrew quite to love Cinderella, and I can't tell you how many times sheheard the story of the glass slipper.

'I know how I came here now!' she exclaimed one afternoon.

'Do you indeed?' was the answer. 'Then, perhaps, you will tell me!'

'I'm like Cinderella,' said Mary. 'Cinderella was very miserable, and Iwas very miserable. Then her fairy-godmother came to make her happy; shegave her all kinds of pretty dresses and things--the fairy-godmotherdid--and some one has given me all kinds of nice things, and taken meaway from William Street and brought me here; so, of course, I know itmust be my fairy-godmother too.' Then Mary was silent for a littlewhile. 'Are you my fairy-godmother?' she asked.

'No,' was the answer. 'I am not nearly important enough to be anybody'sfairy-godmother.'

'Who are you?' asked Mary.

'Well, I am Sister Agatha.'

'Oh, then it wasn't you who brought me here!' said Mary, looking alittle disappointed.

'I wasn't sent for until afterwards,' answered Sister Agatha.

'Who sent for you?' asked Mary.

'The person who brought you here.'

'But who was that?' cried Mary excitedly. 'Please do tell me whether itwas a fairy! I'm sure it was, because it couldn't be any one else, yousee.'

'Then that settles the question,' said Sister Agatha, with a smile, andMary thought it did.

'Where is she?' she asked.

'A long, long way off! She had to go away the day after you came, so sheasked me to take care of you till she saw you again. But she won't belong now.'

'Is she very beautiful like the fairies you've read to me about?' askedMary.

'I don't suppose there ever was anybody so beautiful,' answered SisterAgatha.

'And has she got wings like this?' asked Mary, opening a book that layon the bed and pointing to one of its coloured pictures.

'I shouldn't wonder,' said Sister Agatha; 'only she doesn't show themevery day, because it isn't the fashion to wear wings, you know.'

'I think that's a pity,' answered Mary; and from that day she thought ofscarcely anything else but how she had been brought away from WilliamStreet by her fairy-godmother, just like Cinderella.

Of course, Mary Brown had never imagined that she had afairy-godmother--who could imagine such a thing in William Street! Butthen Cinderella had never imagined that she had a fairy-godmothereither, until the night of the grand ball.

One day Sister Agatha told Mary she might get out of bed; she wascarefully wrapped in a dressing-gown and a blanket and carried to acomfortable arm-chair. On her left foot she wore a pink woollen shoe,but the other foot looked so clumsy in its great bandages, that SisterAgatha covered it over.

'I wish you would untie it,' said Mary; 'I really won't run away. Ishan't run away, because I want to see my fairy-godmother so much.'

'Well,' answered Sister Agatha, 'you will see her very soon now; for sheis coming to-morrow.'