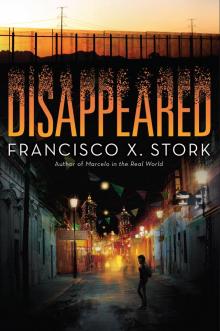

Disappeared

Francisco X. Stork

FOR JOHN A. SYVERSON

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

El Sol

Part I: Mexico

Chapter 1: Sara

Chapter 2: Emiliano

Chapter 3: Sara

Chapter 4: Emiliano

Chapter 5: Sara

Chapter 6: Emiliano

Chapter 7: Sara

Chapter 8: Emiliano

Chapter 9: Sara

Chapter 10: Emiliano

Chapter 11: Sara

Chapter 12: Emiliano

Chapter 13: Sara

Chapter 14: Emiliano

Chapter 15: Sara

Chapter 16: Emiliano

Chapter 17: Sara

Chapter 18: Emiliano

Chapter 19: Sara

Chapter 20: Emiliano

Chapter 21: Sara

Chapter 22: Emiliano

Chapter 23: Sara

Chapter 24: Emiliano

Chapter 25: Sara

Part II: United States

Chapter 26: Emiliano and Sara

Chapter 27: Emiliano and Sara

Chapter 28: Emiliano and Sara

Chapter 29: Emiliano and Sara

Chapter 30: Emiliano

Chapter 31: Emiliano

Chapter 32: Emiliano

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

On the morning of November 14, the day she was kidnapped, Linda Fuentes opened the door to my house and walked into the kitchen, where my family was having breakfast. As usual, I wasn’t ready. Linda and I had an ongoing argument: She said I was always late, and I said she got to my house early to bask in the adoration of my younger brother, Emiliano. But we had been best friends for fourteen years, so we could forgive each other anything. I heard her laughing and chatting with my mother and Emiliano until I was ready to go.

Our routine had been the same every morning for the past two years. We walked the six blocks from my house to Boulevard Pablo II, where we caught a bus that would take us to the Cathedral. From there I would catch another bus to the offices of this newspaper, and Linda walked three blocks to her job at a shoe store on Francisco Villa Avenue. Linda had dropped out of school and taken the job at the shoe store when her father was paralyzed in a construction accident. Her salary, along with a small income that her mother made from sewing, supported her parents and two younger sisters.

Linda always waited with me until my bus arrived. We stayed together as much as possible, partly because most abductions of women in Juárez occur downtown, and partly as protection against the comments of men driving or walking by. Every time a man said something offensive, Linda and I would whisper “puchi” to each other and laugh. I found an empty bus seat that morning—a small miracle—and when I looked out the window, I saw Linda jump up and down in excitement over my good luck. As the bus pulled away, she stuck her tongue out at me.

That was the last time I saw my best friend.

I worked all day at this newspaper. At seven p.m. I got a phone call from Linda’s mother. I knew as soon as I heard Mrs. Fuentes’s shaky voice that something terrible had happened. Linda got off work at four, and she had never been home later than six. If you are a daughter or a sister or a wife in Juárez, the one thing you always do if you are going to be late is call. And if your friend is one hour late and she hasn’t called home, your heart begins to break.

Mrs. Fuentes was hoping against hope that Linda and I had decided to go to the movies after I finished work. She knew we would never do that without calling our families first, but when you are worried, you grasp at straws. Mrs. Fuentes had already called the shoe store where Linda worked, and the owner told her that Linda left a few minutes after four that afternoon. She walked toward the bus station with plenty of time to catch the 4:30 bus that would get her home by six at the latest. Linda usually left with another employee from the store, but that day, she traveled those three blocks alone.

What do you do? Where do you go when your best friend has disappeared, and you know deep inside that the worst has happened? You pray for a miracle, but you act like a detective. I called the bus company and was assured that there were no accidents or other unusual occurrences on Linda’s route. When I got home, I asked a neighbor with a car to drive me downtown on the same streets the bus takes. We parked the car near the Cathedral and walked the blocks that Linda walked every day to her job. We showed Linda’s picture to store owners, to bus drivers, to street vendors. We drove to municipal police headquarters and were told that they had no jurisdiction to investigate missing girls. Later that night, I took Mrs. Fuentes to the State Police, and we were told to go home and wait. “Your daughter’s probably having a drink with a boy,” the officer in charge said, a smirk on his face. We drove to the General Hospital. She wasn’t there. A kind nurse checked with the other hospitals. Nothing.

That night, everyone who knew Linda gathered at her house. Everyone offered Linda’s parents and her sisters hope. We tried to be positive, but we couldn’t shake off what we knew: In ninety percent of Juárez’s missing-girl cases, their bodies are found a month or two later. We agreed to make flyers with Linda’s picture and personal details and decided where to post them. We made a list of all the government authorities, all the groups of mothers of missing daughters who we would contact. We went on Facebook and Twitter and asked for help. Mrs. Fuentes finally cried herself to sleep around six that morning.

It has been almost two months since Linda disappeared. Every week I accompany Mrs. Fuentes to the State Police headquarters and we inquire about Linda. We know what the answer to our questions will be, but we want to keep putting pressure on the police. We want them to know that someone cares. Mr. and Mrs. Fuentes have been called twice to the forensic offices to identify pieces of clothing found on the bodies of young women. I have seen their relief when the clothing is not Linda’s, and then, immediately, the return of the restless, gnawing grief that comes from not knowing what happened to your daughter.

I wake up each morning thinking that I hear Linda’s laughter in the kitchen. When I step into the bus that took us downtown every morning, I look for two seats. Sometimes I think I see her waiting for me with the ice-cream cones we treated ourselves with at the end of the day. But those brief moments of hope quickly disappear, and I feel even more alone, with a sense of her absence so real I can almost touch it.

Maybe in other cities in the world, a young woman can be one hour late and it isn’t a cause for worry. In Juárez, that is simply not possible. It is true that the number of Desaparecidas has greatly diminished over the years, so the number of killings and disappearances is now, as our public officials like to tell us, “comparable to other cities of similar size.” By “comparable” they mean, for example, that the number of disappearances last year was only sixty-four. And by November, when Linda disappeared, there had been only forty-six reported cases of missing girls.

But optimism at the “normal” number of disappearances will never comfort a best friend’s grief. The emptiness I feel can’t be filled with comparisons to other cities or with statistics. Linda, the friend who entered my house every morning without knocking, is missing. And the only way to lessen the pain is to look for her. To keep looking for her for as long as we promised our friendship would last.

I will keep looking for you, my dear friend, forever and ever.

Part I

Mexico

“You need to give up on the missing girls,” Felipe says.

Sara isn’t sure she heard him correctly. Although Felipe’s tone is not harsh, the index finger he points at her makes his words sound like a reprimand. He’s sitting behind his desk, covered in a disordered mess of envelopes and paper. Sara l

ooks at her editor, Juana, who stands up and closes the glass door to the office.

“Look, Sara,” Felipe continues when Juana sits down. “You’ve done a great job with your column, but now it’s time to focus on the good stuff. This is not 2010, when twenty girls went missing every month. Juárez is prospering. Tourists are coming back to the shops, nightclubs are hopping again, Honeywell just opened a new assembly plant. We need to get on board and contribute to creating a positive image. Why don’t you write a weekly column on the new schools opening? The slums getting cleaned up?”

Sara feels Juana’s hand on her arm. Ever since her article on Linda’s disappearance, she’s written a weekly profile of one of the hundreds of girls who have gone missing. That column has been her fight and her comfort, the fulfillment of the promise she made to Linda to never stop looking for her. It cannot be taken away. Juana has always been Sara’s close friend and staunchest advocate, and her touch gives her strength.

Sara speaks as calmly as she can. “You’re right that there aren’t as many girls disappearing as a few years ago, or even a year ago,” she says. “But there are still so many girls who go missing, like Susana Navarro last week. And what about the dozens still unaccounted for? Where are they? Maybe some of them are still alive. The fact that we’re still getting threats is proof that our articles hit a nerve. We’re the only ones keeping the pressure on the government. They’d give up if it wasn’t for us.”

Felipe rubs the back of his head. Sara knows he always has trouble responding to logical arguments. “Bad news doesn’t sell anymore. The newspaper is finally beginning to do well. We went from daily to almost dead to weekly and now we’re biweekly. I don’t want to take a step backwards here. No one wants to buy ads next to pictures of missing girls.”

“But that’s been true for a while now,” Sara says. “Has there been a specific threat?”

Felipe and Juana look at each other. Then he sighs and pushes a single sheet of paper across his desk. It’s a printout of an e-mail.

If you publish anything of Linda Fuentes we will kill your reporter and her family.

Sara reads the e-mail once, then again, pausing on the words kill, reporter, family.

“It was sent to me around six this morning. I forwarded it to you,” Felipe says to Juana. Then, fixing his eyes on Sara: “Are you doing anything with Linda Fuentes? Research, interviews, calling people?”

“No,” Sara says. She’s received threats before, but this is the first time her family has been mentioned. The thought of anyone coming after Emiliano or her mother makes her shudder. But alongside fear, something like hope blooms in her chest. If someone needs to threaten her about Linda, does that mean she’s still alive? She places the sheet of paper on the desk. “I mean, Linda was … is my best friend. I’m still close to her family. They live in my neighborhood, and I go with Mrs. Fuentes to the State Police headquarters every couple of weeks. But I’m not doing anything about Linda that’s related to my job.”

“Well, someone thinks you’re investigating or writing about her.” Felipe leans back in his chair and touches the pocket of his shirt, searching for the cigarettes he gave up smoking a month before. “There’s something weird about this threat. It’s like they know it’s you who’s been writing the column.”

“There hasn’t been a byline on the column since Sara’s article on Linda,” Juana says. “No one knows it’s her.”

“You think those people can keep a secret?” Felipe points with his hand to the room full of cubicles outside his glass wall. “And what is this about family? Since when do families of reporters get threatened? No more articles on missing girls. That’s it.”

“Someone has to keep the memory of these girls alive,” Sara blurts out louder than she intends. She takes a deep breath and looks into Felipe’s eyes. “If we don’t care about them, then who will?”

“Sara,” Juana says softly, “I’m with Felipe on this one. We lost two reporters during the cartel wars. They were both young and enthusiastic like you.” She takes a deep breath. “If our articles were doing any good, maybe it would be worth the risk. But has a single girl turned up since we’ve published these profiles?”

“No,” Sara says. “But if nothing else, the families know their daughters and sisters are not forgotten. That makes a difference.”

“I don’t want to be responsible for another dead reporter,” Felipe says with finality. “No more articles on the Desaparecidas. There’s more to life than just evil and pain, no? Think of something happy for a change. I want a proposal for a positive story on my desk by the end of the day.” To Juana he says, “You better clear your day tomorrow so we can finish that damn budget. That’s all. Let’s get to work.”

Sara stands and walks out of the office. She needs to do something before she speaks—or worse, shouts—the words on the tip of her tongue. She heads for the stairs that connect El Sol’s IT room to the main floor. They are dark and cool, as expected.

She sits on one of the steps and grabs her head. Is it true that all she can see is the suffering and injustice that need fixing? She remembers her first column about Linda, the most personal article she’s ever written. It was a miracle that Juana convinced Felipe to allow one of his reporters to write about something that affected them. In the days that followed the publication of the article, El Sol received dozens of letters from families of missing girls. The article provided hope and comfort to many, and the positive response convinced Juana and Felipe that a regular column on the Desaparecidas was worthwhile. The column has been Sara’s way of keeping Linda alive in her heart—and Felipe just killed it.

Think of something happy for a change. There’s more to life than just evil and pain, no?

She gets up and stands by the steel door that leads back to the newsroom. After a few seconds, she takes a deep breath and opens it.

Think of something happy for a change.

Yes, she can do that. Of course she can do that. Can’t she? She thinks of Mami, getting on with life after Papá left her, making delicious cakes for a bakery. Or her brother, Emiliano, falling in love for the first time, and how he squirmed and blushed when Sara finally got him to tell her the name of the girl he’s smitten with. Just thinking about Emiliano makes Sara happy. He was going down a bad path after Papá left, and now look at him, helping other at-risk kids with his folk art business. Thank God for Brother Patricio and the Jiparis.

The Jiparis, Sara thinks. They’re like the Boy Scouts, holding long hikes out in the desert that save boys from delinquency. That’s a feel-good story if there ever was one. She goes back to her desk and types out a brief proposal; then she attaches it to an e-mail and sends it to Felipe. A message from Juana appears on her screen.

Let’s talk. Can you come over now?

In her office, Juana gestures for Sara to close the door. Sara sits down in one of the yellow plastic chairs in front of the desk.

Juana’s voice is businesslike. “I’m sorry I didn’t support you in there. But this one scares me more than the other e-mails. It mentions a specific girl, and it does seem to be directed at you and … your family.”

“I agree with you that it’s written in a peculiar way,” Sara says. She doesn’t tell Juana that the e-mail scared her too. “It’s the first threat that uses we instead of I. It’s as if it came from a group or an organization of some sort.”

Juana knits her eyebrows the way she does when she’s trying to read someone. “Look, I know you, Sara, and I know that regardless of Felipe’s orders—or mine, for that matter—you’re going to try to find out who and what’s behind this. Don’t. I agree with Felipe. From all kinds of angles, this is not a good idea. You are in danger, and I don’t want anything to happen to you. But also, Felipe is right. It’s not good for business to be pushing negative news right now. We’re finally doing well enough to hire a few more people. We’re working six days a week again. I want you to stand down, as they say in the armed forces. Stand down completely.”

“You don’t really mean that,” Sara says. “That’s not the Juana Martínez I know, who always says where there’s a bad smell, there’s a skunk, and it’s our job to find the skunks. There’s a skunk behind this e-mail. I want to find it.”

“This time I think we need to live with the smell,” Juana says, looking away.

“Juana.” Sara leans forward, waits for Juana to look at her. “When the cartel wars were raging and every newspaper reporter had been threatened, you were one of the few who kept on. Even after El Sol lost two reporters, you continued writing the truth. I remember reading your articles when I was in grade school. You’re the reason I decided to be a reporter. Your courage is why I’m here. You can’t want me to stop looking.”

“It’s different now,” Juana says quietly.

“How?”

“I told you already. This newspaper has to survive.” Then, as if regretting the tone of her words, Juana shakes her head. “Nothing I say is going to stop you, is it?”

“I can’t give up,” Sara says, thinking of Linda.

For a moment, Juana looks almost angry, but she says, “Keep me informed of everything. I mean everything.” She waits for Sara’s nod. “This is not a request. It is an order from your boss.”

“I will. I promise.”

“Here.” Juana picks up a business card and hands it to Sara. “Call this guy. He’s constructing a new mall near Zaragoza. I want you to do an article about why he’s doing it now—what signs he sees in the city and the economy that make him think a new mall will succeed. Go to the site where he plans to build it. Get some pictures.”

Sara holds the card in front of her for a few seconds. “Is this for the happy article Felipe wants me to do? I sent an idea to him a little while ago.”

“No, it’s a favor to someone who’s willing to spend a lot on advertising. This is a business, remember? We can’t do any good if we’re not in business. Do this one after you write the one for Felipe.”