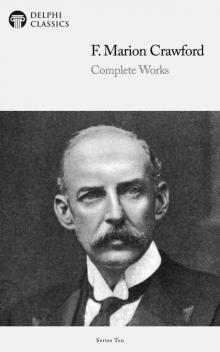

Complete Works of F Marion Crawford

F. Marion Crawford

The Complete Works of

F. MARION CRAWFORD

(1854-1909)

Contents

The Saracinesca Series

The Novels

Mr. Isaacs

Doctor Claudius

To Leeward

A Roman Singer

An American Politician

Zoroaster

A Tale of a Lonely Parish

Saracinesca

Marzio’s Crucifix

Paul Patoff

With the Immortals

Greifenstein

Sant’ Ilario

A Cigarette-Maker’s Romance

Khaled

The Witch of Prague

The Three Fates

Don Orsino

The Children of the King

Pietro Ghisleri

Marion Darche

Katharine Lauderdale

Love in Idleness

The Ralstons

Casa Braccio

Adam Johnstone’s Son

Taquisara

A Rose of Yesterday

Corleone

Via Crucis

In the Palace of the King

Marietta

Cecilia

The Heart of Rome

Whosoever Shall Offend

Soprano

A Lady of Rome

Arethusa

The Little City of Hope

The Primadonna

The Diva’s Ruby

The White Sister

Stradella

The Undesirable Governess

The Shorter Fiction

Wandering Ghosts

The King’s Messenger

The Non-Fiction

Our Silver

The Novel: What It Is

Constantinople

Bar Harbor

Ave Roma Immortalis

Rulers of the South

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2019

Version 1

Browse our Main Series

Browse our Ancient Classics

Browse our Poets

Browse our Art eBooks

Browse our Classical Music series

The Complete Works of

F. MARION CRAWFORD

By Delphi Classics, 2019

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of F. Marion Crawford

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2019.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78877 968 5

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

Parts Edition Now Available!

Love reading F. Marion Crawford?

Did you know you can now purchase the Delphi Classics Parts Edition of this author and enjoy all the novels, plays, non-fiction books and other works as individual eBooks? Now, you can select and read individual novels etc. and know precisely where you are in an eBook. You will also be able to manage space better on your eReading devices.

The Parts Edition is only available direct from the Delphi Classics website.

For more information about this exciting new format and to try free Parts Edition downloads, please visit this link.

The Saracinesca Series

THE TRILOGY

Saracinesca (1887)

Sant’ Ilario (1889)

Don Orsino (1892)

SUBSEQUENT SEQUELS

Corleone (1897)

A Lady of Rome (1906)

The White Sister (1909)

The Novels

Crawford was born in Bagni di Lucca, Italy on 2 August 1854.

Mr. Isaacs

A TALE OF MODERN INDIA

Crawford was born in Bagni di Lucca, Italy on August 2nd 1854. His father, Thomas, was a successful sculptor and his mother was Louisa Ward. Crawford would spend the majority of his childhood in Rome, although he attended St Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, before studying at Cambridge University as well as the University of Heidelberg. In 1879, Crawford sailed for India and soon upon his arrival he began to write articles for local newspapers before taking the position of editor at The Indian Herald. He remained at the paper until the summer of 1880 when he became frustrated by the owner and decided to return to Rome.

Crawford’s first novel, Mr Isaacs: A Tale of Modern India, was published on 5 December 1882 by Macmillan & Co. He had completed the book in June after two months of writing. He had been encouraged to compose the novel by his uncle, Sam Ward, who thought it would be interesting for Crawford to write about his experience of India. Ward was a central figure in Crawford’s life, personally and professionally: he introduced his nephew to publishers and other useful contacts in the literary world.

Mr Isaacs was inspired by Crawford’s time in the country and the people he met there, as well as the stunning landscape. The novel centres on the narrator’s, Paul Griggs, encounters with the eponymous Mr. Isaacs. In one of their earliest meetings, Griggs learns of Isaacs’ painful past and the men become close friends. The novel then traces Isaacs’ ill-fated romance with the woman he loves, Katharine and the powerful effect the relationship has on his journey to spiritual enlightenment.

The first edition

The first edition's title page

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

Portrait of Crawford as a young man, produced for an 1889 edition of the novel

An early frontispiece

The 1931 film adaptation

CHAPTER I.

IN SPITE OF Jean-Jacques and his school, men are not everywhere born free, any more than they are everywhere in chains, unless these be of their own individual making. Especially in countries where excessive liberty or excessive tyranny favours the growth of that class most usually designated as adventurers, it is true that man, by his own dominant will, or by a still more potent servility, may rise to any grade of elevation; as by the absence of these qualities he may fall to any depth in the social scale.

Wherever freedom degenerates into license, the ruthless predatory instinct of certain bold and unscrupulous persons may, and almost certainly will, place at their disposal the goods, the honours, and the preferment justly the due of others; and in those more numerous and certainly more unhappy countries, where the rule of the tyrant is substituted for the law of God, the unwearying flatterer, patient under blows and abstemious under high-feeding, will assuredly make his way to power.

Without doubt the Eastern portion of the world, where an hereditary, or at least traditional, despotism has never ceased since the earliest social records, and where a mode of thought infinitely more degrading than any feudalism has become ingrained in the blood and soul of the chief races, presents far more favourable conditions to the growth and development of the true adventurer than are offered in any free country. For in a free country the majority can rise and overthrow the fa

vourite of fortune, whereas in a despotic country they cannot. Of Eastern countries in this condition, Russia is the nearest to us; though perhaps we understand the Chinese character better than the Russian. The Ottoman empire and Persia are, and always have been, swayed by a clever band of flatterers acting through their nominal master; while India, under the kindly British rule, is a perfect instance of a ruthless military despotism, where neither blood nor stratagem have been spared in exacting the uttermost farthing from the miserable serfs — they are nothing else — and in robbing and defrauding the rich of their just and lawful possessions. All these countries teem with stories of adventurers risen from the ranks to the command of armies, of itinerant merchants wedded to princesses, of hardy sailors promoted to admiralties, of half-educated younger sons of English peers dying in the undisputed possession of ill-gotten millions. With the strong personal despotism of the First Napoleon began a new era of adventurers in France; not of elegant and accomplished adventurers like M. de St. Germain, Cagliostro, or the Comtesse de la Motte, but regular rag-tag-and-bobtail cut-throat moss-troopers, who carved and slashed themselves into notice by sheer animal strength and brutality.

There is infinitely more grace and romance about the Eastern adventurer. There is very little slashing and hewing to be done there, and what there is, is managed as quietly as possible. When a Sultan must be rid of the last superfluous wife, she is quietly done up in a parcel with a few shot, and dropped into the Bosphorus without more ado. The good old-fashioned Rajah of Mudpoor did his killing without scandal, and when the kindly British wish to keep a secret, the man is hanged in a quiet place where there are no reporters. As in the Greek tragedies, the butchery is done behind the scenes, and there is no glory connected with the business, only gain. The ghosts of the slain sometimes appear in the columns of the recalcitrant Indian newspapers and gibber a feeble little “Otototoi!” after the manner of the shade of Dareios, but there is very little heed paid to such visitations by the kindly British. But though the “raw head and bloody bones” type of adventurer is little in demand in the East, there is plenty of scope for the intelligent and wary flatterer, and some room for the honest man of superior gifts, who is sufficiently free from Oriental prejudice to do energetically the thing which comes in his way, distancing all competitors for the favours of fortune by sheer industry and unerring foresight.

I once knew a man in the East who was neither a flatterer nor freebooter, but who by his own masterly perseverance worked his way to immense wealth, and to such power as wealth commands, though his high view of the social aims of mankind deterred him from mixing in political questions. Bon chien chasse de race is a proverb which applies to horses, cattle, and men, as well as to dogs; and in this man, who was a noble type of the Aryan race, the qualities which have made that race dominant were developed in the highest degree. The sequel, indeed, might lead the ethnographer into a labyrinth of conjecture, but the story is too tempting a one for me to forego telling it, although the said ethnographer should lose his wits in striving to solve the puzzle.

In September, 1879, I was at Simla in the lower Himalayas, — at the time of the murder of Sir Louis Cavagnari at Kabul, — being called there in the interests of an Anglo-Indian newspaper, of which I was then editor. In other countries, notably in Europe and in America, there are hundreds of spots by the sea-shore, or on the mountain-side, where specific ills may be cured by their corresponding antidotes of air or water, or both. Following the aristocratic and holy example of the Bishops of Salzburg for the last eight centuries, the sovereigns of the Continent are told that the air and waters of Hofgastein are the only nenuphar for the over-taxed brain in labour beneath a crown. The self-indulgent sybarite is recommended to Ems, or Wiesbaden, or Aix-la-Chapelle, and the quasi-incurable sensualist to Aix in Savoy, or to Karlsbad in Bohemia. In our own magnificent land Bethesdas abound, in every state, from the attractive waters of lotus-eating Saratoga to the magnetic springs of Lansing, Michigan; from Virginia, the carcanet of sources, the heaving, the warm, the hot sulphur springs, the white sulphur, the alum, to the hot springs of Arkansas, the Ultima Thule of our migratory and despairing humanity. But in India, whatever the ailing, low fever, high fever, “brandy pawnee” fever, malaria caught in the chase of tigers in the Terai, or dysentery imbibed on the banks of the Ganges, there is only one cure, the “hills;” and chief of “hill-stations” is Simla.

On the hip rather than on the shoulder of the aspiring Himalayas, Simla — or Shumla, as the natives call it — presents during the wet monsoon period a concourse of pilgrims more varied even than the Bagnères de Bigorre in the south of France, where the gay Frenchman asks permission of the lady with whom he is conversing to leave her abruptly, in order to part with his remaining lung, the loss of the first having brought him there. “Pardon, madame,” said he, “je m’en vais cracher mon autre poumon.”

To Simla the whole supreme Government migrates for the summer — Viceroy, council, clerks, printers, and hangers-on. Thither the high official from the plains takes his wife, his daughters, and his liver. There the journalists congregate to pick up the news that oozes through the pent-house of Government secrecy, and failing such scant drops of information, to manufacture as much as is necessary to fill the columns of their dailies. On the slopes of “Jako” — the wooded eminence that rises above the town — the enterprising German establishes his concert-hall and his beer-garden; among the rhododendron trees Madame Blavatzky, Colonel Olcott and Mr. Sinnett move mysteriously in the performance of their wonders; and the wealthy tourist from America, the botanist from Berlin, and the casual peer from Great Britain, are not wanting to complete the motley crowd. There are no roads in Simla proper where it is possible to drive, excepting one narrow way, reserved when I was there, and probably still set apart, for the exclusive delectation of the Viceroy. Every one rides — man, woman, and child; and every variety of horseflesh may be seen in abundance, from Lord Steepleton Kildare’s thoroughbreds to the broad-sterned equestrian vessel of Mr. Currie Ghyrkins, the Revenue Commissioner of Mudnugger in Bengal. But I need not now dwell long on the description of this highly-favoured spot, where Baron de Zach might have added force to his demonstration of the attraction of mountains for the pendulum. Having achieved my orientation and established my servants and luggage in one of the reputed hotels, I began to look about me, and, like an intelligent American observer, as I pride myself that I am, I found considerable pleasure in studying out the character of such of the changing crowd on the verandah and on the mall as caught my attention.

At last the dinner-hour came. With the rest I filed into the large dining-room and took my seat. The place allotted to me was the last at one side of the long table, and the chair opposite was vacant, though two remarkably well-dressed servants, in turbans of white and gold, stood with folded arms behind it, apparently awaiting their master. Nor was he long in coming. I never remember to have been so much struck by the personal appearance of any man in my life. He sat down opposite me, and immediately one of his two servants, or khitmatgars, as they are called, retired, and came back bearing a priceless goblet and flask of the purest old Venetian mould. Filling the former, he ceremoniously presented his master with a brimming beaker of cold water. A water-drinker in India is always a phenomenon, but a water-drinker who did the thing so artistically was such a manifestation as I had never seen. I was interested beyond the possibility of holding my peace, and as I watched the man’s abstemious meal, — for he ate little, — I contrasted him with our neighbours at the board, who seemed to be vying, like the captives of Circe, to ascertain by trial who could swallow the most beef and mountain mutton, and who could absorb the most “pegs” — those vile concoctions of spirits, ice, and soda-water, which have destroyed so many splendid constitutions under the tropical sun. As I watched him an impression came over me that he must be an Italian. I scanned his appearance narrowly, and watched for a word that should betray his accent. He spoke to his servant in Hindustani, and I notice

d at once the peculiar sound of the dental consonants, never to be acquired by a northern-born person.

Before I go farther, let me try and describe Mr. Isaacs; I certainly could not have done so satisfactorily after my first meeting, but subsequent acquaintance, and the events I am about to chronicle, threw me so often in his society, and gave me such ample opportunities of observation, that the minutest details of his form and feature, as well as the smallest peculiarities of his character and manner, are indelibly graven in my memory.

Isaacs was a man of more than medium stature, though he would never be spoken of as tall. An easy grace marked his movements at all times, whether deliberate or vehement, — and he often went to each extreme, — a grace which no one acquainted with the science of the human frame would be at a loss to explain for a moment. The perfect harmony of all the parts, the even symmetry of every muscle, the equal distribution of a strength, not colossal and overwhelming, but ever ready for action, the natural courtesy of gesture — all told of a body in which true proportion of every limb and sinew were at once the main feature and the pervading characteristic. This infinitely supple and swiftly-moving figure was but the pedestal, as it were, for the noble face and nobler brain to which it owed its life and majestic bearing. A long oval face of a wondrous transparent olive tint, and of a decidedly Oriental type. A prominent brow and arched but delicate eyebrows fitly surmounted a nose smoothly aquiline, but with the broad well-set nostrils that bespeak active courage. His mouth, often smiling, never laughed, and the lips, though closely meeting, were not thin and writhing and cunning, as one so often sees in eastern faces, but rather inclined to a generous Greek fullness, the curling lines ever ready to express a sympathy or a scorn which, the commanding features above seemed to control and curb, as the stern, square-elbowed Arab checks his rebellious horse, or gives him the rein, at will.