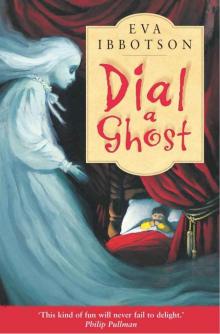

Dial-A-Ghost

Eva Ibbotson

Dial a Ghost

Eva Ibbotson writes for both adults and children. Born in Vienna, she now lives in the north of England. She has a daughter and three sons, now grown up, who showed her that children like to read about ghosts, wizards and witches ‘because they are just like people but madder and more interesting’. She has written seven other ghostly adventures for children. Which Witch? was runner-up for the Carnegie Medal and The Secret of Platform 13 was shortlisted for the Smarties Prize. Her novel Journey to the River Sea won the Smarties Prize and was shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal.

‘You’ll love this chain-rattlingly, blood-oozingly hilarious story’

Daily Telegraph

‘Eva Ibbotson is on top form with this highly entertaining story’

Lindsey Fraser, Scotsman

‘Warm, funny, scary and exciting – this is an absolute gem of a book’

Jonathan Weir, School Librarian

Also by Eva Ibbotson

The Great Ghost Rescue

Which Witch?

The Haunting of Hiram

Not Just a Witch

The Secret of Platform 13

Monster Mission

Journey to the River Sea

The Star of Kazan

The Beasts of Clawstone Castle

For older readers

A Song for Summer

Dial a Ghost

Eva Ibbotson

MACMILLAN CHILDREN’S BOOKS

First published 1996 by Macmillan’s Children’s Books

This edition published 2001 by Macmillan Children’s Books

This electronic edition published 2008 by Macmillan Children’s Books

a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

20 New Wharf Rd, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-330-47767-3 in Adobe Reader format

ISBN 978-0-330-47766-6 in Adobe Digital Editions format

ISBN 978-0-330-47768-0 in Mobipocket format

Copyright © Eva Ibbotson 1996

The right of Eva Ibbotson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.panmacmillan.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you’re always first to hear about our new releases.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter One

The Wilkinson family became ghosts quite suddenly during the Second World War when a bomb fell on their house.

The house was called Resthaven after the hotel where Mr and Mrs Wilkinson had spent their honeymoon, and you couldn’t have found a nicer place to live. It had bow windows and a blue front door and stained glass in the bathroom, and a garden with a bird table and a lily pond. Mrs Wilkinson kept everything spotless and her husband, Mr Wilkinson, was a dentist who went to town every day to fill people’s teeth, and they had a son called Eric who was thirteen when the bomb fell. He was a Boy Scout and had just started having spots and falling in love with girls who sneered at him.

Also living in the house were Mrs Wilkinson’s mother, who was a fierce old lady with a dangerous umbrella, and Mrs Wilkinson’s sister Trixie, a pale, fluttery person to whom bad things were always happening.

The family had been getting ready to go to the air raid shelter at the bottom of the garden and they were collecting the things they needed. Grandma took her umbrella and her gas mask case which did not hold her gas mask but a bottle labelled poison which she meant to drink if there was an invasion rather than fall into enemy hands. Mrs Wilkinson gathered up her knitting and unhooked the budgie’s cage, and Eric took a book called Scouting for Boys and the letter he was writing to a girl called Cynthia Harbottle.

In the hall they met Mr Wilkinson, who had just come in and was changing into his khaki uniform. He belonged to the Home Guard, a brave band of part-time soldiers who practised crawling through the undergrowth and shooting things when they had finished work.

‘Hurry up everyone,’ he said. ‘The planes are getting closer.’

But just then they remembered that poor Trixie was still in her upstairs bedroom wrapped in a flag. The flag was her costume for a show the Women’s Institute was putting on for the gallant soldiers, and Trixie had been chosen to be The Spirit of Britain and come on in a Union Jack.

‘I’ll just go and fetch her,’ said Mrs Wilkinson, who knew that Trixie had not been at all happy with the way she looked and might be too shy to come down and join them.

She began to climb the stairs ... and then the bomb fell and that was that.

Of course it was a shock realizing that they had suddenly become ghosts.

‘Fancy me a spook!’ said Grandma, shaking her head.

Still, there they were – a bit pale and shimmery, of course, but not looking so different from the way they had before. Grandma always wore her best hat to the shelter, the one with the bunch of cherries trimmed with lover’s knots, and the whiskers on her chin stuck out like daggers in the moonlight. Eric was in his Scout uniform with the woggle and the badge to show he was a Pathfinder, and his spectacles were still on his nose. Only the budgie didn’t look too good. He had lost his tail feathers and seemed to have become rather a small bird.

‘Oh, Henry, what shall we do now?’ asked Mrs Wilkinson. The top half of her husband was dressed like a soldier in a tin hat which he had draped with leaves so as to make him look like a bush, but the bottom half was dressed like a dentist and Mrs Wilkinson, who loved him very much, glided close to him and looked up into his face.

‘We shall do what we did before, Maud,’ said Mr Wilkinson. ‘Live decent lives and serve our country.’

‘At least we’re all together,’ said Grandma.

But then a terrible silence fell and as the spectres looked at each other their ectoplasm turned as white as snow.

‘Where is Trixie?’ faltered Mrs Wilkinson. ‘Where is my dear sister?’

Where indeed? They searched what was left of the house, they searched the garden, they called and called, but there was no sign of a shy spook with spectacles dressed in nothing but a flag.

For poor Maud Wilkinson this was an awful blow. She cried, she moaned, she wrung her hands. ‘I promised Mother I would look after her,’ she wailed. ‘I’ve always looked after Trixie.’

This was true. Maud and Trixie’s mother had run a stage dancing school and ever since they were little, Maud

had helped her nervy sister to be a Sugar Puff or Baby Swan or Dandelion.

But there was nothing to be done. Why some people become ghosts and others don’t is a mystery that no one has ever solved.

The next years passed uneventfully. The war ended but nobody came to rebuild their house and the Wilkinsons lived in it much as they did before. It was completely ruined but they could remember where all the rooms were, and in a way being a ghost is simple; you don’t feel the cold or have to go to school, and they soon got the hang of passing through walls and vanishing. Having Mr Wilkinson to explain things to them was a great help of course.

‘You have to remember,’ he said, ‘that while people are made of muscle and skin and bone, ghosts are made of ectoplasm. But that does not mean,’ he went on sternly, ‘that we can allow ourselves to become feeble and woozy and faint. Ectoplasm can be strengthened just the way that muscles can.’

But however busy they were doing knee bends and press-ups and learning to move things by the power of their will, they never forgot poor Trixie. Every single evening as the sun went down they went into the garden and called her. They called her from the north, they called her from the south and the east and the west but the sad, goose-pimpled spook never appeared.

Then, when they had been phantoms for about fifteen years, something unexpected happened. They found the ghost of a lost child.

They were out for an early morning glide in the fields near their house when they saw a white shape lying in the grass, under the shelter of a hedge.

‘Goodness, do you think it’s a passed-on sheep?’ asked Mrs Wilkinson.

But when they got closer they saw that it was not the ghost of a sheep that lay there. It was the ghost of a little girl. She wore an old-fashioned nightdress with a ribbon round the neck and one embroidered slipper, and though she was fast asleep, the string of a rubber sponge bag was clasped in her hand.

‘She must be a ghost from olden times,’ said Mrs Wilkinson excitedly. ‘Look at the stitching on that nightdress! You don’t get sewing like that nowadays.’

‘She looks wet,’ said Grandma.

This was true. Drops of water glistened in her long, tousled hair and her one bare foot looked damp.

‘Perhaps she drowned?’ suggested Eric.

Mr Wilkinson opened the sponge bag. Inside it was a toothbrush, a tin of tooth powder with a picture of Queen Victoria on the lid – and a fish. It was a wild fish, not the kind that lives in tanks, but it too was a ghost and could tell them nothing.

‘It must have floated into the sponge bag when she was in the water,’ said Mr Wilkinson.

But the thing to do now was to wake the child, and this was difficult. She didn’t seem to be just asleep; she seemed to be in a coma.

In the end it was the budgie who did it by saying ‘Open wide’ in his high squawking voice. He had learnt to say this when his cage hung in the dentist’s surgery because it was what Mr Wilkinson said to his patients when they sat down in the dentist’s chair.

‘Oh the sweet thing!’ cried Mrs Wilkinson, as the child stirred and stretched. ‘Isn’t she a darling! I’m sure she’s lost and if she is, she must come and make her home with us, mustn’t she, Henry? We must adopt her!’ She bent over the child. ‘What’s your name, dear? Can you remember what you’re called?’

The girl’s eyes were open now, but she was still not properly awake. ‘Adopt ... her,’ she repeated. And then in a stronger voice, ‘Adopta.’

‘Adopta,’ repeated Mrs Wilkinson. ‘That’s an odd name – but very pretty.’

So that was what she came to be called, though they often called her Addie for short. She never remembered anything about her past life and Mr Wilkinson, who knew things, said she had had concussion, which is a blow on the head that makes you forget your past. Mr and Mrs Wilkinson never pretended to be her parents (she was told to call them Uncle Henry and Aunt Maud), but she hadn’t been with them for more than a few weeks before they felt that she was the daughter they had always longed for – and the greatest comfort in the troubled times that now began.

Because life now became very difficult. Their house was rebuilt and the people who moved in were the kind that couldn’t see ghosts. They thought nothing of putting a plate of scrambled eggs down on Grandma’s head, or running the Hoover through Eric when he wanted to be quiet and think about why Cynthia Harbottle didn’t love him.

And when they left, another set of people moved in who could see ghosts, and that was even worse. Every time any of the Wilkinsons appeared they shrieked and screamed and fainted, which was terribly hurtful.

‘I could understand it if we were headless,’ said Aunt Maud. ‘I’d expect to be screamed at if I was headless.’

‘Or bloodstained,’ agreed Grandma. ‘But we have always kept ourselves decent and the children too.’

Then the new people stopped screaming and started talking about getting the ghosts exorcized, and after that there was nothing for it. They left their beloved Resthaven and went away to find another home.

Chapter Two

The Wilkinsons went to London thinking there would be a lot of empty houses there, but this was a mistake. No place was more bombed in the war and it was absolutely packed with ghosts. Ghosts in swimming baths and ghosts in schools, ghosts whooping about in bus stations, ghosts in factories and offices or playing about with computers. And older ghosts too, from a bygone age: knights in armour wandering round Indian takeaways, wailing nuns in toy shops, and all of them looking completely flaked out and muddled.

In the end the Wilkinsons found a shopping arcade which didn’t seem too crowded. It had all sorts of shops in it: shoe shops and grocer’s shops and sweet shops and a bunion shop which puzzled Adopta.

‘Can you buy bunions, Aunt Maud?’ she asked, looking at the big wooden foot in the window with a leather bunion nailed to one toe.

‘No, dear. Bunions are nasty bumps that people get on the side of their toes. But you can buy things to make bunions better, like sticking plaster and ointments.’

But the bunion shop was already haunted by a frail ghost called Mr Hofmann, a German professor who had made himself quite ill by looking at the bowls for spitting into, and the rubber tubes, and the wall charts showing what could go wrong with people’s livers – which was plenty.

So they went to live in a knicker shop.

Adopta called it the Knicker Shop but of course no one can make a living just by selling knickers. It sold pyjamas and swimsuits and nightdresses and vests, but none of them were at all like the pyjamas and swimsuits and vests the Wilkinsons were used to.

‘In my days knickers were long and decent, with elastic at the knee and pockets to keep your hankie in,’ grumbled Grandma. ‘And those bikinis! I was twenty-five before I saw my first tummy button, and look at those hussies in the fitting rooms. Shameless, I call it.’

‘It’s the children I’m bothered about,’ said Aunt Maud. ‘They shouldn’t be seeing such things.’

And really some of the clothes sold in that shop were not nice! – suspender belts that were just a row of frills, and see-through slips and transparent boxes full of briefs.

‘Brief whats?’ snorted Grandma.

Still they really tried to settle down and make a life for themselves. Adopta was put to sleep in the office, where she wouldn’t be among pantalettes and tights with rude names, and Uncle Henry stayed among the socks because there is a limit to how silly you can get with socks. They hung the budgie’s cage on the rack beside the Wonderbras and told themselves that they were lucky to have a roof over their heads at all.

But they were not happy. The shopping arcade was stuffy, the people wandering up and down it looked greedy and bored. They missed the garden at Resthaven and the green fields, and although they went out and called Trixie every night, they couldn’t help wondering whether a shy person dressed in a flag would dare to appear in such a crowded place even if she heard them.

Aunt Maud did everything she could to make t

he knicker shop into a proper home. She arranged cobwebs on the ceiling and brought in dead thistles from the graveyard and rubbed mould into the walls, but the lady who sold the knickers was a demon with the floor polisher. She was another one who couldn’t see ghosts and, though they slept all day and tried to keep out of her way, she was forever barging through them or spinning the poor budgie round as she twiddled the Wonderbras on their stand. Grandma was getting bothered about Mr Hofmann in the bunion shop who was coming up with more and more diseases – and Eric had started counting his spots again and writing awful poetry to Cynthia Harbottle.

‘But Eric, we’ve been ghosts for years and years!’ his mother would cry. ‘Cynthia’d be a fat old lady by now.’

But this only hurt Eric who said that to him she would always be young, and he would glide off to the greetings card shop to see if he could find anything to rhyme with Cynthia, or Harbottle, or both.

‘Oh, Henry, do you think we shall ever have a proper home again?’ poor Maud would cry. And her husband would pat her back and tell her to be patient, and never let on that when he was pretending to go to the dental hospital to study new ways of filling teeth, he was really house hunting, and had found nothing at all.

But Aunt Maud’s worst worry was about Adopta. Addie was becoming a street ghost. She often stayed out all night and she was picking up bad habits and mixing with completely the wrong sort of ghost: ghosts who had been having a bath when their house caught fire and hadn’t had time to put on any clothes; the ghosts of rat-catchers and vulgar people who swore and drank in pubs.

And she was bringing in the most unsuitable pets.

Addie had always been crazy about animals. She liked living animals, but of course for a ghost to drag living animals about is silly, and the ones that held her heart were the creatures that had passed on and become ghosts and didn’t quite understand what had happened to them. But it was one thing to fill the garden at Resthaven with phantom hedgehogs and rabbits and moles, and quite another to keep a runover alley cat or a battered pigeon among the satin pyjamas and the leotards.