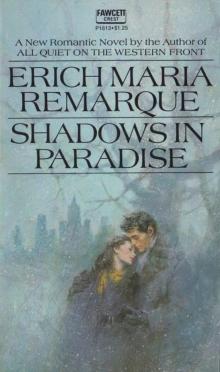

Shadows in Paradise

Erich Maria Remarque

"with these powerful threads of passion Remarque weaves, with sometimes startling in sights, the swiftly moving, haunting story of men and women in their years without a country. It bears the hallmark of Remarque's classic ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT and properly caps his lifelong efforts to describe man's noble conflict with his world."

—NASHVILLE BANNER

Fawcett Crest Books

by Erich Maria Remarque:

ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT

THE NIGHT IN LISBON

SHADOWS IN PARADISE

SHADOWS IN PARADISE

THIS BOOK CONTAINS THE COMPLETE TEXT OF THE

ORIGINAL HARDCOVER EDITION.

A Fawcett Crest Book reprinted by arrangement with

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Copyright © 1971 by Paulette Remarque

English translation copyright © 1972 by Paulette Remarque,

Executrix of the Estate of Erich Maria Remarque

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book

or portions thereof in any form.

All the characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance

to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-174513

Alternate Selection of the Literary Guild, April 1972

Originally published in Germany under the title

Schatten im Paradies by Droemer Knaur

Printed in the United States of America

April 1973

PROLOGUE

I lived in New York during the last phase of the Second World War. Despite my deficient English the midtown section of New York became for me the closest thing to a home I had experienced in many years.

Behind me lay a long and perilous road, the Via Dolorosa of all those who had fled from the Hitler regime. It led from Germany to Holland, Belgium, northern Prance, and Paris. From Paris some proceeded to Lyons and the Mediterranean, others to Bordeaux, the Pyrenees, and across Spain and Portugal to Lisbon.

Even after leaving Germany we were not safe. Only a very few of us had valid passports or visas. When the police caught us, we were thrown into jail and deported. Without papers we could not work legally or stay in one place for long. We were perpetually on the move.

In every town we stopped at the post office, hoping to find letters from friends and relatives. On the roads we scrutinized every wall for messages from those who had passed through before us: addresses, warnings, words of advice. The walls were our newspapers and bulletin boards. This was our life in a period of universal indifference, soon to be followed by the inhuman war years, when the Milice, often seconded by the police, joined forces with the Gestapo against us.

I

I had arrived a few months before on a freighter from Lisbon and knew little English—it was as though I had been dropped deaf and dumb from another planet. And indeed America was another planet, for Europe was at war.

Besides, my papers were not in order. Thanks to a series of miracles I had entered the country with a valid American visa; but the name on the passport was not mine. The immigration authorities had had their suspicions and held me on Ellis Island. After six weeks they had given me a residence permit good for three months, during which time I was supposed to obtain a visa for some other country. I was familiar with this kind of thing from Europe. I had been living this way for years, not from month to month, but from day to day. And, as a German refugee, I had been officially dead since 1933. Not to be a fugitive for three whole months was in itself a dream come true. And living with a dead man's passport had long ceased to strike me as strange—on the contrary, it seemed fitting and proper. I had inherited the passport in Frankfurt Since the name of the man who had given it to me just before he died had been Ross, my name was now Ross. I had almost forgotten my real one. You can forget a lot of things when your life is at stake.

On Ellis Island I had met a Turk who had spent some time in America ten years before. I didn't know why they were not re-admitting him, and I didn't ask. I had seen too many people deported from any number of countries merely because some official questionnaire did not cover their case. The Turk gave me the address of a Russian living in New York who, on his flight from Russia twenty years before, had been helped by the Turk's father. The Turk had been to see him some years before, but didn't know if he was still alive. The day they released me from the island I took a chance and looked him up. Why not? I had been living like that for years. Lucky breaks were a fugitive's only hope.

The Russian, who called himself Melikov, worked in a small run-down hotel not far from Broadway. He took me right in. As an old refugee, he saw at a glance what I needed: lodging and a job. Lodging was no problem; he had an extra bed, which he set up in his room. A job was a little more complicated. My tourist visa didn't entitle me to work. Anything I found would have to be clandestine. That, too, was known to me from Europe and didn't bother me particularly. I still had a little money.

"Have you any idea what you could do for a living?" Melikov asked me.

"I last worked in France as a salesman for a dealer in dubious paintings and phony antiques."

"Do you know anything about the business?"

"Not much; some of the usual dodges."

"Where did you learn that?"

"I spent two years in the Brussels Museum."

"Working?" Melikov asked in surprise.

"No, hiding."

"From the Germans?"

"From the Germans who had occupied Belgium."

"Two years? And they didn't find you?"

"No," I said. "Not me. But after two years they caught the man who was hiding me."

Melikov looked at me in amazement "And you got away?"

"Yes."

"Any news of the other fellow?"

"The usual. They sent him to a camp."

"A German?"

"A Belgian. The curator of the museum."

Melikov nodded. "How could you stay there so long without being discovered? Didn't anybody ever visit the museum?"

"Oh yes. In the daytime he locked me up in a storeroom in the cellar. After closing time he brought me food and let me out for the night. I had to stay in the museum, but at least I was out of the cellar. Of course I couldn't use any light"

"Did any of the employees know about you?"

"No. The storeroom had no windows. I had to be vefy quiet when anyone came down to the cellar. My main worry was sneezing."

"Is that how they discovered you?"

"No. Somebody noticed that the curator often stayed in the museum at closing time—or went back later."

"I see," said Melikov. "Could you read?"

"Only at night. During the summer or when the moon was shining."

"But at night you could wander around the museum and see the pictures?"

"As long as there was light enough."

Suddenly Melikov smiled. "When I was escaping from Russia, I spent six days lying under a Woodpile on the Finnish border. When I came out, I thought it had been much longer. At least two weeks. But I was young then; the time passes more slowly when you're young." And then abruptly: "Are you hungry?"

"Yes," I said. "Starving, in fact."

"I thought so. They've just let you out. That always makes a man hungry. We'll get something to eat at the pharmacy."

"Pharmacy?"

"Sure, the drugstore. One of this country's oddities. They sell you aspirin and they feed you."

I looked down the row of people hastily eating at the long counter. "What do you eat in a place like this?" I asked.

"A hamburger. The poor man's stand-by. Steak costs too much for the common man.

"What

did you do in the daytime in the museum?" Melikov asked. "To keep from going crazy?"

"I waited for evening. Of course I did everything in my power to keep from thinking of the danger I was in. I'd been running from place to place for several years, first in Germany for a year, then in other countries. I shut out every thought of the mistakes I had made. Regret corrodes the soul; it's a luxury you can afford only in peaceful times. I said all the French I knew over to myself; I gave myself lessons. Then I began exploring the museum at night, looking at the pictures, imprinting them on my memory. Soon I knew them all by heart. Then in the daytime, in the darkness of my storeroom, I'd call them to mind. Not at random, but systematically, picture by picture. Sometimes I'd spend whole days on a single painting. Now and then I broke off in despair, but I always started in again. This memory exercise made me feel that I was improving myself. I'd stopped knocking my head against the wall; now I was climbing a flight of stairs. Do you see what I mean?"

"You kept moving," said Melikov. "And you had an aim. That saved you."

"I lived one whole summer with Cézannes and a few Degas—imaginary pictures of course and imaginary comparisons. But comparisons, nevertheless, and that made them a challenge. I memorized the colors and the compositions, though I'd never seen the colors by daylight. The pictures I memorized and compared were moonlight Cézannes and twilight Degas. Later on, I found art books in the library; I huddled under the windows and studied them. The world (hey gave me was a world of specters, but still a world."

"Wasn't the museum guarded?"

"Only in the daytime. At night they locked it up. Which was lucky for me."

"And unlucky for the man who brought you your meals."

I looked at Melikov. "And unlucky for the man who'd hidden me," I answered calmly. I could see that he meant no harm; he wasn't chiding me, but merely stating the facts.

"Don't get any ideas about clandestine dishwashing," he said. "That's romantic nonsense. Besides, the unions won't stand for it these days. How long can you hold out without working?"

"Not very long. How much is this meal going to cost?"

"A dollar and a half. Prices have gone up since the war started."

"There's no war here."

"Oh yes, there is," said Melikov. "Which is luck for you again. They need men. That'll make it easier for you to find something."

"I've got to leave the country in three months."

Melikov laughed and screwed up his little eyes. "The U.S. is a big place. And there's a war on. Another stroke of luck for you. Where were you born?"

"According to my passport, in Hamburg. Actually in Hanover."

"They can't deport you to either of those places. But they could put you in an internment camp."

I shrugged my shoulders. "I was in one of those in France."

"Escaped?" ' "Not exactly. I just walked out. In the general confusion of the defeat."

Melikov nodded. "I was in France myself. In the general confusion of a supposed victory. In 1918. I'd come from Russia by way of Finland and Germany. The first wave of latter-day migrations."

We went back to the hotel, but I was restless. I didn't want to drink, the worn plush of the lounge didn't appeal to me, and Melikov's room was too small. I had been shut up long enough. "How late can I stay out?" I asked.

"As long as you please."

"When do you go to bed?"

"Don't let that worry you. Not before morning. I'm on duty now. You want a woman? They're not as easy to find in New York as in Paris. And a little more dangerous."

"No. I just feel like roaming around."

"You'll find a woman more easily right here in the hotel."

"I don't need one."

"Go on!"

"Not tonight."

"You're a romantic," said Melikov. "Remember the street number and the name of the hotel: Hotel Reuben. It's easy to find your way in New York. Most of the streets are numbered; only a few have names."

Like me, I thought—a number with a meaningless name. The anonymity suited me: names had brought me too much trouble.

I drifted through the anonymous city. Luminous smoke rose heavenward. A pillar of fire by night and a pillar of cloud by day—wasn't that how God had shown the first nation of refugees the way through the desert? I passed through a rain of words, noise, laughter, and shouts that beat meaninglessly on my ears. After the dark years in Europe, everyone I saw here seemed to be a Prometheus— the perspiring man standing in his shop door in a blaze of electric light, who thrust out an armful of socks, and towels in my direction and implored me to buy, or the cook I.saw through an open door standing like a Neapolitan Vulcan in the blaze of his oven. Since I didn't understand what they said, the people I saw, the waiters, cooks, touts, and street vendors, looked to me like figures on a stage, marionettes playing an incomprehensible game from which I was excluded. I was there in their midst but not one of them; between us there was an invisible barrier, no hostility on their part but something inside me that concerned no one but myself. I was dimly aware that this was a unique moment, which would never come again.

The next day this feeling would be gone. Not that I'd have come any closer to these people. Far from it. Tomorrow or the day after I'd throw myself into the struggle for a livelihood, the daily round of parry and thrust, of deceptions and half-lies, but tonight the city held out its impartial face to me like a monstrance, every feature etched in the finest filigree. It had not yet caught me up in its net, but confronted me as equal to equal. Time seemed to stand still, as though for this one moment in the darkness the great scales were evenly balanced between active and passive.

Here I was in this haven of safety—out of danger. And now suddenly it came to me that the real danger was not outside me but within myself. For years my only thought had been sheer survival, and this had given me a kind of inner security. But tomorrow, or, rather, from this strange moment on, life would spread out before me in all its richness. Again there would be a future, but there would also be a past that might easily crush me unless I could forget it or come to terms with it.

Suddenly I realized that this was the beginning of a new life. But was it possible to start over again from scratch? To make myself at home in this new, unknown language? And, most frightening of all after all these years of fighting for survival, to learn once more how to live? And if I succeeded in coming back to life, would I not be betraying all my dead friends and loved ones?

I turned around. Confused and deeply troubled, I hurried back to the hotel, no longer looking at my surroundings. I was out of breath when I finally caught sight of the dismal little neon sign over the entrance.

The door was inlaid with dingy strips of false marble, one of which was missing. I went in and saw Melikov dozing in a rocking chair behind the desk. He opened his eyes. For a moment they seemed fixed and lidless, like those of an aged parrot; then they moved and I saw that they were blue. He stood up and asked: "Do you play chess?"

"All refugees play chess."

"Good. I'll get the vodka."

He went up the stairs. I looked around me as though I had come home after a long absence. That is an easy feeling to get when you have no home.

II

I devoted the next few weeks to learning English. In the morning I sat in the red plush lobby with a grammar and in the afternoon I practiced conversation. After the first ten days, it dawned on me that I was catching Melikov's Russian accent. So I brazenly latched on to anyone who would talk to me. From the hotel guests I acquired, successively, a German, a Jewish, and a French accent; then, confident that the waitresses and chambermaids at least would be real Americans, a thick Brooklyn patois.

"An American girl friend is what you need," said Melikov.

"From Brooklyn?" I asked.

"Better find one from Boston. That's where they speak the best English."

"Vladimir," I said, "my world is changing quickly enough as it is. Every few days my American ego grows a year older and the world

loses a little of its enchantment The more I understand, the more the mystery seeps away. In another few weeks my American ego will be as disabused as my European one. So don't rush me. And don't worry about my accent I'm in no hurry to lose my second childhood."

"No danger. Right now you have the intellectual horizon - of a melancholy greengrocer. The one on the corner, Anni-bale Balbo."

"Is there such a thing as a real American?"

"Of course there is. But New York is the great port of entry for immigrants—Irish, Italian, German, Jewish, Armenian, Russian, and then some. What is it they used to say in your country? 'Here you're a man and allowed to be one.' Well, here you're a refugee and allowed to be one. This country was built by refugees. So get rid of your European inferiority complex. Here you're a man again. You've stopped being a bruised chunk of flesh with a passport attached to it."