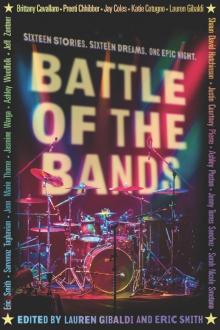

Battle of the Bands

Eric Smith

Miss Somewhere Brittany Cavallaro

Cecilia (You’re Breaking My Heart) Ashley Poston

Sidelines Sarah Nicole Smetana

Battle of the Exes Sarvenaz Taghavian

Love Is a Battlefield Shaun David Hutchinson

You Found Me Ashley Woodfolk

Adventures in Babysitting Justin Courtney Pierre

Peanut Butter Sandwiches Jasmine Warga

Reckless Love Jay Coles

The Ride Jenn Marie Thorne

Three Chords Eric Smith

Merch to Do About Nothing Preeti Chhibber

All These Friends and Lovers Katie Cotugno

A Small Light Jenny Torres Sanchez

Set the World on Fire Lauren Gibaldi

The Sisterhood of Light and Sound Jeff Zentner

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

Beckett Scibelli didn’t believe in omens. But if she did, she would’ve bailed out of her family’s U-Haul in the middle of I-70 and run screaming along the median all the way back to Peoria, Illinois, and let her family go to New Jersey without her.

The first omen was her snare drum disappearing the morning before they moved. She’d almost had a heart attack when she couldn’t find it. Then it reappeared — hey, presto — in her parents’ empty walk-in closet the minute before they locked up the condo for good. “I don’t know, Becks,” her dad said while the two of them played furniture Jenga, trying to stuff the drum into the overstuffed truck. “Did leprechauns do it? Real industrious mice? Did you maybe do it in your sleep?”

“Don’t listen to him,” her mom said, hopping down from the cab. She lifted the bill of her Cardinals cap and wiped the sweat from her brow. “You know your father. When he’s distracted, he picks things up and just . . . takes them places.”

“It’s like I give them a little vacation.” Her dad waggled his eyebrows. “I whisk them off on mysterious missions, off into the great unknown . . .”

“Billy.” Her mom giggled. “Stop it!”

Her mom thought her dad was hilarious, which was good. Someone had to.

It was Beckett’s cue to make a gagging sound, so she did, wiggling the snare bag in next to the one that held her floor tom. Their gigantic coffee table wobbled threateningly over her drum kit, and she shot it a look. “Stay,” she told it. Then: “Hailey, when you were packing up the basement . . . are you sure you didn’t move my snare?”

Her twin was uncharacteristically quiet, staring down their driveway into the condos across the street like she could see straight through them into the fields beyond. “No,” Hailey said, and without another word, she got into the minivan. She’d convinced their parents to let them drive it so she and Beckett could say goodbye to Peoria together, on their own terms. Beckett had sort of imagined them rolling down the windows, yelling BYE, SUNOCO STATION and BYE, STEAK ’N SHAKE and BYE-BYE, PHS, like a pair of giddy overgrown toddlers.

But Hailey didn’t talk at all that day, just brooded out the windshield behind her scratched-up Clubmasters while Beckett said goodbye in her head.

The second omen was when their family stopped for the night at a Holiday Inn Express in Zanesville, Ohio. “Zany Zanesville,” Beckett said, but Hailey didn’t even smile. The parking lot was packed, and so they followed the U-Haul to the mall lot across the street. She turned off the engine and just sat there for a long moment, her hands still clutching the steering wheel.

“You okay, Hay?” Beckett asked. She’d been trying to give her space, but this was pretty dramatic, even for her sister.

Hailey swallowed, looked up at the ceiling. “I hate Holiday Inn Express,” she said, and slammed her way out of the car.

Beckett took their duffel out of the trunk and followed. “Did Danny text you and I just not see it, or —”

Both girls looked reflexively at the U-Haul. Their parents were still in the cab, looking at something together on their mom’s phone.

“Do you think I would be this upset if Danny had texted me?” Hailey hissed.

“I don’t know! Maybe! I mean, if Dad saw you? Or if Danny texted and told you he was happy you were leaving? Or if he texted and told you he had, like, tattooed your name across his forehead —”

Hailey’s mouth twitched. “That would make me mad?”

“It wouldn’t?” Beckett grinned, dropping the duffel between them on the asphalt. The air shimmered in the early-evening heat. “Your name, three-inch Gothic letters, the y, like, curling down into his eyeball —”

“I don’t know, loverpants. Three-inch letters? That’s commitment.”

“Can’t get mad about that,” Beckett said as kindly as she could, because Hailey was cheering up, and because she knew as well as Hailey did that Danny was a major douchebag who probably started hooking up with Jenna Marten the second the Scibellis pulled out of Peoria.

“I’ll be okay,” Hailey said, picking up their bag. Their parents were clambering down from the truck, finally, laughing like they always were, the two of them in on some really bad private joke. “I just wish I was as okay as you are. You are so okay with all of this, leaving the Sleepyheads behind and everything. How are you okay?”

Beckett grabbed Hailey’s hand and squeezed it. “We have our own music. We have Miss Somewhere. We’re gonna be okay.”

And then they turned toward the road, and there it was, omen number two, with a lease space available sign on the door: a faded old husk of a Guitar Center. She could see the shadows where the lettering used to be.

That would’ve been bad enough, but Hailey dropped her hand and ran toward the door.

“Hay, what are you —?”

She tugged on the handle. “Locked,” she said. “Too bad. I would’ve grabbed it for you.”

Just inside the glass, on the other side of the door, a hi-hat cymbal lolled like the head of a horror-movie clown.

“Shit.” On instinct, Beckett made the sign of the cross.

“Kiddos, you coming?” their dad yelled from the crosswalk.

“Okay, Mother Teresa,” Hailey said, a little spooked. “Let’s go get you some minibar M&M’s so you can chill the hell out.”

Omen number three bided its time. It waited through the rest of their drive to New Jersey until they unpacked most of their boxes into the echoing, giant house their mom got with her new marketing job in Manhattan. Her commute into the city was about an hour, and so that first Monday, their dad dropped her off at the train station, then swung over to deposit Hailey and Beckett at Raritan River High School. It was huge.

“All of Peoria could fit inside there,” Beckett said, staring up at it through the window, “and there would probably be room for Springfield, too.” Hailey just grinned.

“Call me if you need me,” their dad called, too loud, as Beckett snatched her backpack out of the back seat. Kids turned to look. Someone snickered, because of course they did.

At the front office, Beckett and Hailey got their schedules and compared them as they pushed their way through the hall. It was actual pushing: the hallway was wall to wall with people and their bags and their elbows, nothing like PHS back home. Beckett sidestepped a bunch of emo kids and almost brained herself on an open locker door.

“Jesus H. Christ,” she said. They pulled up by the locker deck they’d been assigned, and Beckett began twirling her combination lock with shaking fingers. “This is monstrous. I knew it was going to be bad coming in on the third week, but I didn’t know how bad. This is nothing like PHS —”

Hailey was only half listening. The whole of the Raritan River soccer team was streaming by, chanting what sounded like “GO, KEG, GO.”

“That can’t be right,” Beckett said. “‘Keg’?”

“I think they were saying ‘Ken,’ loverpants.�

�

“Are you sure? What if the school mascot’s a keg? What kind of school is this, anyway?”

“Beck, what happened to okay? I thought you were okay.”

“I left my okay in Zanesville, Ohio,” Beckett said, “at the Guitar Center Haunted House.” And when she finally yanked her locker open, omen number three came pouring out.

Some idiot had left a Taco Bell bag in the locker over the summer and the bottom of the bag had rotted out because there was a burrito in there.

Well. It used to be a burrito. Now it was the rancid, runny memory of a burrito, its rancid, runny juices looking like black mold, running out of the locker.

All over her Zildjian T-shirt.

Beckett yelled something foul, dropped her backpack, and began to yank the shirt off over her head.

“Beck”— Hailey sounded like she was laughing (God, if she was laughing) —“you can’t just strip in the middle of the hallway!”

“Burrito!” Beckett said, trying not to puke. “Burrito, Hay!”

“You can’t be naked on the first day of school!”

“I am wearing”— tug —“a tank top”— tug —“underneath!”

But the collar of the shirt was caught around her chin, and she was gagging on the smell of the burrito mung through the cloth. She’d been wearing a bunch of chokers, and her dark hair in two long braids, and her favorite cut-up jeans, and a pair of amazing knock-off Chloé studded boots, and her Zildjian shirt, because she was a drummer, because it was her first day at this awful school and she wanted to look like who she was.

And now the shirt was stuck on her chokers and she was, well, choking.

“Hailey,” she howled just as the bell rang.

The hall went silent.

When Beckett finally got the shirt up over her head, Hailey was gone. Beckett threw her T-shirt in the trash.

Beckett was not okay through first period physics, which she didn’t have with Hailey, or through second period AP English lit, which she did. Hailey tried to grab her before class to apologize. “I’m so sorry. I knew you would be fine and I didn’t want to be late and I freaked!”

“You,” Beckett said, “laughed at me.”

“Well.” Hailey had the good sense to look embarrassed. “It was pretty much the worst thing I’d ever seen. You still smell like burrito mung.”

“Dammit, Hay —”

“Ladies,” the teacher said from inside the classroom. He was frowning down at his iPad. “My attendance roster tells me I have two new Scibellis in this class. Are you my new Scibellis?”

“We are your Scibellis,” Hailey said.

“Take us to your leader,” Beckett said.

No one laughed. No one even looked at them; they were too busy whispering and looking at one another’s phones. With a sigh, the teacher marked something on his iPad. “Take a seat,” he said. “You’re lucky you’ve only missed two weeks — we’re still talking about Jane Eyre. And in the future, Miss . . . Tank Top Scibelli, our dress code doesn’t allow for spaghetti straps. I’ll let it pass since you’re new, but next time, you’re headed full speed to the office.”

Beckett nodded jerkily and sat down in the closest open seat before he could lecture her any more. Hailey tried to make eye contact, but Beckett took out two pencils and her laptop and forced herself to breathe. She wasn’t good at confrontation. She wasn’t good at being bad at things, or talking to lots of people, or anything this first day was throwing at her.

Back home, Hailey had had four zillion friends, a straight-B average, and a job at the Triple Dip scooping ice cream.

Beckett had had Hailey.

Okay, yes, Beckett had been the drummer for the Sleepyheads, who’d been getting gigs at U of I bars an hour and a half away, but her bandmates were all in college. They had been getting tired of the third degree from the promoter about their Kid Wonder Drummer every time they booked a show, and now that she was finally eighteen and a senior and less of a liability, she’d left the state. It was all moot. Beckett had good grades, even in her honors classes, because, though she wasn’t a genius, she knew how to study; she had a lot of patience for practicing, period, so she was really good at the drums. On the weekends, she played a lot of video games with good stories and read thrillers on the sofa. It was a small life, well curated. It didn’t need to have a lot in it if the things in it were beautiful.

Because what she had was Hailey, and in the fairy-lighted wonderland of their Illinois basement, they had had two guitars and a synth and a drum set. They had had Miss Somewhere.

But as the year went on, Beckett had Hailey less and less.

By the end of the first week, Hailey had joined drama club. By the end of the third week, Hailey had quit drama club to start doing sound and production design for the musicals and concerts and performances at RRHS. But she was still friends with all the actors, and then with the band kids, and then with the orchestra kids, and soon Beckett sort of didn’t know where Hailey had met the girl whose toenails she was painting in the living room. “This is Katrina,” Hailey said, dipping her brush back into Beckett’s bottle of Essie Ballet Slippers. From the tutus and tiaras and green face makeup on the coffee table, it looked like they were doing prep for Halloween. The next day at school was costume day.

“Hi, Katrina,” Beckett said. She scratched her temple with a drumstick; she was on her way down to the basement. “Hailey, not to suck, but I thought we were going to . . . practice tonight? I almost have the chorus worked out for that song I told you about.”

“Shit,” Hailey said, and looked at Katrina like she was waiting for permission to go. Katrina looked down at her toes. They were half painted.

“Never mind,” Beckett said as breezily as she could, and breezed on, breezily, down the basement stairs.

“You can always work on your costume with us!” Hailey yelled after her.

“I’m not going to be an undead ballerina!” Beckett yelled back.

“How did you know we were going to be undead ballerinas?”

“You were an undead ballerina last year!”

“So were you!”

“That’s my whole point!” Beckett yelled, and stormed back up to the living room. She made accidental, awkward eye contact with Katrina, who was playing with her bright red hair and trying to look invisible. Then she made awkward eye contact with Hailey, who grimaced, and then she looked at the hardwood floor. It was so much nicer than the carpet in their old house. Beckett hated it.

“We were going to be the twins from The Shining this year,” she said to her feet. “We decided in May. That’s all.” And when Hailey didn’t say anything else, she went back down to the basement and began pounding out a Rush drum solo, double time, until her palms ached. She’d hung all the twinkle lights, set up Hailey’s synth. She’d even found the old My Bloody Valentine and Jesus and Mary Chain posters and taped them to the wall behind Hailey’s mic stand.

But Hailey didn’t come down to apologize.

Beckett broke a stick and, panting, made a decision. She’d play a game: How long would it take before Hailey noticed she was mad? It was easier to play that game, to play it hard, than to deal with the fact that Hailey’s life now had nothing to do with her.

Beckett got a job serving breakfast in the cafeteria for the zero-hour students, and so she biked the twenty minutes to school while it was still warm. After school a few days a week, she biked to work at a Chipotle in the strip mall a few blocks from their house. By the time it started snowing in December, she’d put together enough money, when she added in what she’d saved from her last job in Peoria, to buy herself a junky 2003 VW Bug. Sure, it broke down all the time, and yeah, the passenger side window was always rolling down in a thunderstorm, so when she wasn’t working or studying or practicing the drums, she was watching YouTube videos about car wiring. Her life. It was scintillating.

“Beckett ‘Scintillating’ Scibelli,” she muttered to herself in the freezing garage, popping the hood of

Barry the Bug. Again.

“Sure you’re not going to scramble your brains, kid?” her dad asked, poking his head out from the kitchen. Beckett could smell her dad’s snickerdoodle cookies cooling on the counter. It was Christmas break. Beckett had pretty much stopped talking to her twin altogether. Not that Hailey had really noticed.

“I don’t love you playing with the car so much,” he went on, shutting the door behind him. “If you need help, we can throw in some cash for you to take it to the mechanic. That’s something we can afford to do now, you know. It’s good that we’re here in Jersey.”

Beckett shrugged. As she leaned over the engine, she stuck her flashlight between her teeth so she didn’t have to answer any more questions.

Her dad walked over and gently removed it. “I can hold that,” he said before she could protest.

“Thanks,” Beckett said, and then just sort of stood there, holding a pair of pliers, looking at nothing, because she knew if she looked at her dad at all she was going to start crying.

“You should talk to Hailey,” her dad said after a minute. “I can tell you miss her.”

“I’m just really busy,” she said, “with work and school and everything.”

It was the excuse she’d been building so carefully for the last few months. It sounded like hot garbage out loud.

Her dad heard it, too. He rested a hand on her shoulder. “Hey. Hey, kid, look at me.”

Beckett did. Immediately she started crying. “Dammit,” she said. He hugged her until her sniffling stopped.

After she washed her hands and her face and bolted three snickerdoodles standing over the sink, Beckett brought a stack of them and a mug of cocoa up to Hailey’s bedroom.

“Hay?” she said, half knocking with her shoe.

The door swung open. Her twin had her phone pressed to her ear, and it sort of looked like she was crying. What? Hailey mouthed.

Are you actually talking on the phone? Beckett mouthed back, but it was too much to get across silently, so she whispered it.

“Yes,” Hailey said, and “No, sorry,” into the phone, and before Beckett could say anything else, she grabbed two of the snickerdoodles, lightning fast, and snapped the door shut. Beckett could hear her say, “No, just Beck . . . No, I don’t know. Still bad. No, she just . . . doesn’t have time for me anymore. And she doesn’t seem to think that’s a problem.”