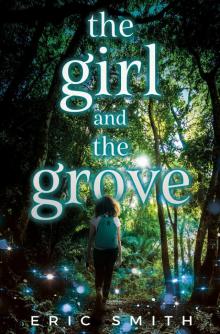

The Girl and the Grove

Eric Smith

Eric Smith

Mendota Heights, Minnesota

The Girl and the Grove © 2018 by Eric Smith. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Flux, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

First Edition

First Printing, 2018

Book design by Jake Nordby

Cover design by Jake Nordby

Cover images by dmbaker/iStockphoto; André Cook/Pexels; 123dartist/Shutterstock

Interior images by Christopher Urie (page 189); Mikey Ilagan (page 362)

Flux, an imprint of North Star Editions, Inc.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Cover models used for illustrative purposes only and may not endorse or represent the book’s subject.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Eric (Eric A.), author.

Title: The girl and the grove / Eric Smith.

Description: First edition. | Mendota Heights, Minnesota : Flux, 2018. |

Summary: "Adopted teen Leila discovers that her connection to nature and passion for environmental activism are part of her unique and magical genetic makeup, and a grove of trees that holds a mythical secret"—

Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017055585 (print) | LCCN 2018001150 (ebook) | ISBN

9781635830194 (hosted e-book) | ISBN 9781635830187 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: | CYAC: Identity—Fiction. | Adoption—Fiction. | Environmental

protection—Fiction. | Dryads—Fiction. | Magic—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.S633 (ebook) | LCC PZ7.1.S633 Gir 2018 (print) |

DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017055585

Flux

North Star Editions, Inc.

2297 Waters Drive

Mendota Heights, MN 55120

www.fluxnow.com

Printed in the United States of America

For every kid who’s been asked

“Where are you from?”

and had a tough time answering.

And as always, for Nena.

I

Lightning split the willow in two, and the voices in Leila’s head shattered.

The smell of burnt bark and charred leaves lingered in the air as Leila stepped into her new family’s backyard, closing the large, plate-glass patio door behind her. She walked briskly towards the willow tree, gritting her teeth, as the voices screamed with the roaring wind. She stepped over some of the branches and tiny fires on the ground, still smoldering like little candles scattered about the earth. With the ruined tree in front of her, she reached out and brushed her fingers where the lightning had made its cut.

The heat from the crack scorched her fingertips, and she pulled back quickly as the voices, which usually whispered in her head, let out another roaring, anguished cry.

With closed eyes, she shook her head, pressing them to go away. Taking deep breaths, Leila focused on what felt real around her, a routine she’d been running through all her life, one she and Sarika had developed together at the group home when the voices came. Say the words. Get present. Be here.

“Grass,” she whispered, pacing her breath as the voices faded. “Rain. Wind. Cold.”

As the voices pulled back into the depths of her mind, as they always did, she looked back up at the ruined tree.

Gone was the cool-to-the-touch bark, a dark brown spotted with slightly darker specks. It had a pattern that she saw a little of herself in; her brown skin freckled in the warmer weather just the same way. Patches of the bark were discolored in places where a piece peeled away, revealing the lighter colors underneath. Her freckles came in little bursts on her face, her shoulder, her forearm, and the larger splash of cream on the right side of her face: a birthmark.

What bark wasn’t burnt off by the crackling electricity that had ripped through the tree was seared crisp, and bits of black soot came off on her fingers when she ran her hands along the surface. Instead of the welcoming, thick, V-shaped branches that grew close enough to grasp simultaneously, like two fingers waving a peace sign, there was only one branch now. She had spent so many afternoons this summer reading and reflecting on those branches, and now one sprawled out on the ground amidst burned grass and shrubbery. The once-beautiful limb looked as though it had roasted in a campfire pit, the bark like burnt, discarded charcoal, and the end where it once connected with the willow replaced with blackened, splintered wood. She looked up from the split to the rest of the tree, which still bloomed bright green, as though the other half of the old willow was unaware of what had happened.

It broke Leila’s heart.

Her willow was dead, but the rest of the tree didn’t know it yet.

But maybe there was a way to save it. If she couldn’t do it, maybe an arborist, one of those tree doctors she’d seen posting on the Urban Ecovists board she frequented with Sarika, or in articles on various local environmental news sites. She’d read that one had recently gone into Clark Park in West Philadelphia to help save a rare American Chestnut tree, which was definitely news to Leila. Who knew any kind of chestnuts were endangered?

She walked over to the half of the tree that was sprawled out on the earth and searched for any remaining bits of green, twigs that were unscathed from the lightning, but quickly turned her attention back to the still-standing section of the willow. She reached up and touched a low-hanging branch, bracing herself for the voices to come. They stayed silent, the bark still cool and wet.

“Okay,” Leila said, exhaling. “Let’s do this.”

She took a few steps back and took a running jump to grip the slick branch, grabbing it hard, her hands slipping a bit but holding firm. She kicked herself up off the broken trunk and wrapped herself around a thick limb.

She climbed up, inching her way quickly despite how wet the surface was. She could feel the rain that the hurricane had brought soaking into her jeans and t-shirt, and the fabric clung to her skin as she shimmied on up. The cold, eye-of-the-storm winds chilled her as she pushed forward, yet she smiled, a girl on a mission.

She was thinking of Sarika and Major Oak.

Back in the group home, she’d worked her way through a heaping majority of the limited library. It consisted mostly of classics donated by well-meaning liberal arts graduates of one of the nearby universities, probably Temple or St. Joseph’s, who apparently never spoke to one another about their donations. The result was several stacks of the same exact book again and again, likely from finished English literature courses, which irritated some of the other children and teens who came through the place.

But Leila didn’t mind the collections. It gave her an excuse to try and form book clubs with the other kids in the house. Including Sarika. Four years back, when Sarika had arrived at the home on the same day as a massive stack of Jamie Ford’s Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet (likely donated from some first-year college English class), they quietly read copies together on the home’s way-too-soft couch. Sarika only stopped to cry a little every few chapters.

“So,” Sarika had said, closing the book as it grew dark outside. “What else you got here?”

They’d been inseparable ever since.

Leila drew closer to the top of the large willow, where branches burst this way and th

at, pushing out and then plummeting down under the weight of the long, green leaves. She thought fondly of the first book club she’d put together with Sarika back in the home.

Some students had dropped off a stack of Alexandre Dumas’s Prince of Thieves, and another failed foster family had left Leila back at the home the same day. Leila found solace in the pages, holed up with Sarika and their books. But when stories of made-up families and their adventures failed, she sought out words about her own family in the only place she could.

The Internet.

With every near miss and failed family came the searching: on Google, adoption message boards, and anywhere else she could think of.

“Why do you do this? What are you hoping to find?” Sarika would ask, flicking back her thick, black hair before crossing her arms, her heavy eyebrows furrowed. “Ambiguously brown couple dies in tragic train derailment, but not before bequeathing millions of dollars to the daughter they put up for adoption so many years ago. Leila Hetter, please come to City Hall to collect your inheritance and the deeds to your four mansions.”

“Well,” Leila had started with a laugh.

“Here, I’ll show you something better to strive for,” Sarika had said that day, nudging Leila away from the computer and taking over the search.

“Major Oak,” she’d typed.

It turned out Robin Hood’s hideout, Major Oak, was in fact a real tree, one still growing in the actual Sherwood Forest. That had begun a tradition of entering the annual lottery to claim a sapling from Major Oak. Each year Sarika and Leila waited in front of the computer at their group home or in the Philadelphia Public Library, watching the clock count down, signing up to win a baby tree during the limited time frame.

They never won, which Leila thought was probably for the best, considering the cost of the saplings and the fact that a tree wasn’t going to thrive in their group home. Hell, the kids hardly did. But it did bring the girls closer together.

Leila sat up, her legs holding on tight to the willow’s remaining limb, and snapped some smaller twigs and sticks off one of the branches. She checked each one as she pulled them back, making sure the inside still revealed signs of life, bright green over the white wood. Once she’d gathered a small bundle, she let them go and watched them fall to the ground. A few stragglers clicked softly against the tree’s branches as they worked their way down, and one or two got stuck in the hanging leaves.

Once back on the ground, she gathered up the twigs and shook them to get the rain off before she brought them into the house.

“Leila!” a familiar voice shouted. She looked up to spot Jon, her foster-parent-now-newly-adoptive-parent, running towards her. The small fires around the yard had since petered out in the soft rain, wisps of smoke barely visible in the growing dawn.

“Careful, there’s a lot of branches on the ground!” Leila shouted, holding the small twigs close to her chest.

“Me be careful?” Jon scoffed. “You get in here! The storm is going to pick back up any minute! What were you thinking?”

Leila hustled towards the house with Jon, and when they reached the door, he put a supportive hand on her shoulder as she walked inside. Leila shrugged it away and walked right to the sink while Jon closed the door behind her.

“Any chance you’re going to explain what you were doing out there?” Jon asked.

Leila placed the twigs and small branches in one of the two large sinks in her new family’s kitchen. She turned the faucet on, letting the water run gently over them, filling the dishwashing bin slowly. Satisfied she had enough water, she looked around the kitchen and made her way to the pantry, which hid inside a large closet. She slowly opened the door, wincing at the soft squeak it made as it swung open, and flicked on the light. The soft glow illuminated the colored mason jars that lined every inch of space in there.

“Leila?” Jon asked, concern tinting his voice. “Come on now, what are you doing?”

Red-and-yellow peppers, bright-green pickles and spicy jalapenos, jars of jam and marmalade in hues of orange, pink, and blue—Mrs. Kline’s love of the local farmer’s market subscription service and Mr. Kline’s passion for pickling and jarring made them the perfect pairing. It was taking some getting used to, calling them Liz and Jon, instead of Mr. or Mrs. Kline. They’d insisted, especially if she wasn’t ready to use . . . well, those other words. Not yet. Leila smiled as she pulled several empty jars from the bottom of Jon’s treasure trove. It was endearing and quirky, in a way. No other family ever treated her this way, the two of them so casual and aloof, and so grossly in love with one another.

And they didn’t fuss over her like she was someone . . . different. Asking stupid questions about how to wash her hair, or freaking out every time the seasons changed. The group home was honest about her seasonal affective disorder, and every foster family she had found herself with had pushed and pressed about it.

The sun is awfully bright today. Will you be okay?

We’re thinking of going to the beach, but you know, it gets hot out there.

Have you ever tried not being depressed when it’s cold out?

It’s snowing. How are you feeling?

None of those had anything to do with her depression, and every comment was more infuriating than the last. And although the diagnosis had come quickly from a clearly inexperienced doctor at an understaffed clinic near the group home in Philadelphia, she’d spent years before that reading up every little thing she could about it. As long as it wasn’t on the Internet, where reading about a cough could make you think you had some sort of rare incurable disease. She knew her stuff, even if the nervous, quivering young doctor had looked as though he was in dire need of sleep and some studying.

No, it seemed like Jon and Lisabeth had actually done their homework, and not just with her illness. She definitely had Lisabeth to thank for the that stuff. Lisabeth had the right shampoo and conditioner, the sulfate-free kind that could be rather expensive, for Leila’s thick hair which she loved to let grow natural. Lisabeth kept hers short with weaved-in, thick braids, but knew all the best products like the back of her hand.

They let her take her meds without any serious helicoptering. And since she was the only child, there weren’t any younger kids to ask her dumb questions about her therapeutic light box. The last foster home she was in, one of the kids thought it was a Lite Brite, and shocked himself when he broke it with small plastic pieces.

She found herself back at the group home a week after that incident, a thick bruise blooming on her cheek from “falling down the stairs.”

A heaviness swelled in her chest at the thought, threatening to take her out of the moment and away from her mission at hand. She fought against it, closing her eyes to push the darkness away.

“So, uh, brushing up on canning?”

Leila jumped, almost dropping the jars she had bundled in her arms.

“Hah! Easy there,” Jon said, a soft smile on his face. “I see you’ve decided to follow in your ol’ man’s footsteps, and start pickling. I’m . . . I’m so proud right now.” He feigned wiping a tear from his eye, and then crossed his arms and stared at her silently, his mouth still turned in that accusatory grin he was so good at. “Though it’s a slightly odd time to start. Storm and all.”

“What?” Leila asked, shifting uncomfortably. All that “ol’ man” talk that Jon was so fond of always made her feel a bit weird. It’d had only been a few months, here in this new home, even less time since the adoption went through. And while the Klines certainly didn’t seem like they’d be going anywhere anytime soon, at least not without her, the mom-and-dad-type talk made her incredibly uneasy. Especially when Jon was so quick to toss it around, goofy as he was.

It wasn’t fair to toss words around like that, when they could be taken away just as quickly as they were said.

And they often were.

She’d seen i

t. She’d felt that sting before.

“What’s going on with all the sticks?” he asked, nodding at the sink.

“They’re from the willow,” Leila said, trying to hide the melancholy in her voice as she made her way over to the sink and looked down at the snapped-off twigs. A bubble of pain blossomed inside her chest and she pushed it back down. She nodded towards the kitchen’s large bay window, which showed off a view of the backyard and the now-split tree. “After that, she’s probably not going to make it.”

“She?” Jon asked, still smiling.

“Yes, like all living things that give life on this planet, the willow is a she,” Leila said with a smirk. She reached into the sink and plucked out one of the willow’s sticks, examining the end where she’d broken it.

“Ah, my little feminist,” Jon said, beaming proudly. “You’ve got something right here—” Leila felt Jon picking something out of her hair. She shot her head back and gave him a scowl.

“Jon! Come on, man, don’t touch my hair!” she shouted, running her hands over her thick curls that took an eternity to get just right. Granted, it was all a mess right now after climbing up the tree, but still. He had to learn. She figured he should know better after all these years with Liz.

“Sorry, sorry! You had some leaves,” Jon said, still smiling. “I’m working on that.”

“I know. Thanks. I appreciate it,” Leila said, returning to look at the sticks. She opened one of the kitchen drawers and plucked out her Leatherman, a multi-tool she used when out fussing in the gardens with Jon or pruning shrubs in front of the house. He’d given it to her a couple of days after she’d gotten settled in the new home, when he caught her staring through the bay window at him and Liz working in the garden. This was one of the many endearing quirks that Jon had, his misguided attempts at being sweet and the “cool” parent, like giving Leila—mostly a complete stranger—a knife less than a week after she arrived. She smiled, thinking of the fight he’d had with Liz about it, as she slid it out of its worn fabric case. Bits of frayed string stuck out this way and that, and she opened the silver-colored gadget to the tucked-away blade inside.