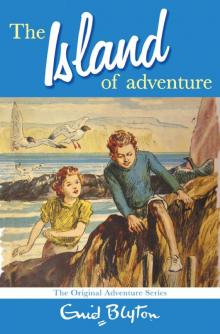

The Island of Adventure

Enid Blyton

Enid Blyton, who died in 1968, is one of the most successful children’s authors of all time. She wrote over seven hundred books, which have been translated into more than 40 languages and have sold more than 400 million copies around the world. Enid Blyton’s stories of magic, adventure and friendship continue to enchant children the world over. Enid Blyton’s beloved works include The Famous Five, Malory Towers, The Faraway Tree and the Adventure series.

Titles in the Adventure series:

1. The Island of Adventure

2. The Castle of Adventure

3. The Valley of Adventure

4. The Sea of Adventure

5. The Mountain of Adventure

6. The Ship of Adventure

7. The Circus of Adventure

8. The River of Adventure

First published 1944 by Macmillan Children’s Books

This electronic edition published 2009 by Macmillan Children’s Books

an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Rd, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-330-50701-1 in Adobe Reader format

ISBN 978-0-330-50700-4 in Adobe Digital Editions format

ISBN 978-0-330-50702-8 in Mobipocket format

Text copyright © Enid Blyton Limited. All rights reserved. Enid Blyton’s signature mark is a trademark of Enid Blyton Limited (a Chorion company). All rights reserved.

The right of Enid Blyton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.panmacmillan.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you’re always first to hear about our new releases.

Contents

1. The beginning of things

2. Making friends

3. Two letters – and a plan

4. Craggy-Tops

5. Settling in at Craggy-Tops

6. The days go by

7. An odd discovery

8. In the cellars

9. A strange boat

10. Night adventure

11. Bill Smugs

12. A treat – and a surprise for Joe

13. Joe is tricked again

14. A glimpse of the Isle of Gloom

15. A peculiar happening – and a fine trip

16. Strange discoveries

17. Joe is angry

18. Off to the island again

19. Down in the copper mines

20. Prisoners underground

21. Escape – but what about Jack?

22. A talk with Bill – and a shock

23. Another secret passage

24. A journey under the sea

25. An extraordinary find

26. A bad time – and a surprising meeting

27. A lot of things are made clear

28. Trapped

29. All’s well that ends well

1

The beginning of things

It was really most extraordinary.

There was Philip Mannering, doing his best to puzzle out algebra problems, lying full-length under a tree with nobody near him at all – and yet he could hear a voice speaking to him most distinctly.

‘Can’t you shut the door, idiot?’ said the voice, in a most impatient tone. ‘And how many times have I told you to wipe your feet?’

Philip sat up straight and took a good look round for the third time – but the hillside stretched above and below him, completely empty of any boy, girl, man or woman.

‘It’s so silly,’ said Philip to himself. ‘Because there is no door to shut, and no mat to wipe my feet on. Whoever is speaking must be perfectly mad. Anyway, I don’t like it. A voice without a body is too odd for anything.’

A small brown nose poked up out of Philip’s jersey collar. It belonged to a little brown mouse, one of the boy’s many pets. Philip put up a gentle hand and rubbed the tiny creature’s head. Its nose twitched in delight.

‘Shut the door, idiot!’ roared the voice from nowhere, ‘and don’t sniff. Where’s your handkerchief?’

This was too much for Philip. He roared back.

‘Shut up! I’m not sniffing. Who are you, anyway?’

There was no answer. Philip felt very puzzled. It was uncanny and peculiar. Where did that extraordinary voice with its rude commands come from, on this bright, sunny but completely empty hillside? He shouted again.

‘I’m working. If you want to talk, come out and show yourself.’

‘All right, Uncle,’ said the voice, speaking unexpectedly in a very different tone, apologetic and quiet.

‘Gosh!’ said Philip. ‘I can’t stand this. I’ll have to solve the mystery. If I can find out where the voice comes from, I may find its owner.’ He shouted again. ‘Where are you? Come out and let me see you.’

‘If I’ve told you once I’ve told you a dozen times not to whistle,’ answered the voice fiercely. Philip was silent with astonishment. He hadn’t been whistling. Evidently the owner of the voice must be completely mad. Philip suddenly felt that he didn’t want to meet this strange person. He would rather go home without seeing him.

He looked carefully round. He had no idea at all where the voice came from, but he rather thought it must be somewhere to the left of him. All right, he would go quietly down the hill to the right, keeping to the trees if he could, so that they might hide him a little.

He picked up his books, put his pencil into his pocket and stood up cautiously. He almost jumped out of his skin as the voice broke out into cackles of laughter. Philip forgot to be cautious and darted down the hillside to the shelter of a clump of trees. The laughter stopped suddenly.

Philip stood under a big tree and listened. His heart beat fast. He wished he was back at the house with the others. Then, just above his head, the voice spoke again.

‘How many times have I told you to wipe your feet?’

Then there came a most unearthly screech that made poor Philip drop his books in terror. He looked up into the tree near by, and saw a beautiful white parrot, with a yellow crest on its head that it worked up and down. It gazed at Philip with bright black eyes, its head on one side, its curved beak making a grating noise.

Philip stared at the parrot and the parrot stared back. Then the bird lifted up a clawed foot and scratched its head very thoughtfully, still raising and lowering its crest. Then it spoke.

‘Don’t sniff,’ it said, in a conversational tone. ‘Can’t you shut the door, idiot? Where are your manners?’

‘Golly!’ said Philip, in amazement. ‘So it was you talking and shouting and laughing! Well – you gave me an awful fright.’

The parrot gave a most realistic sneeze. ‘Where’s your handkerchief?’ it said.

Philip laughed. ‘You really are a most extraordinary bird,’ he said. ‘The cleverest I ever saw. Where have you escaped from?’

‘Wipe your feet,’ answered the parrot sternly. Philip laughed again. Then he heard the sound of a boy’s voice, calling loudly from the bottom of the hill.

>

‘Kiki, Kiki, Kiki! Where have you got to?’

The parrot spread out its wings, gave a hideous screech, and sailed away down the hillside towards a house set at the foot. Philip watched it go.

‘That was a boy calling it,’ he thought. ‘And he was in the garden of Hillfoot House, where I’m staying. I wonder if he’s come there to be crammed too. I jolly well hope he has. It would be fine to have a parrot like that living with us. It’s dull enough having to do lessons in the hols – a parrot would liven things up a bit.’

Philip had had scarlet fever the term before, and measles immediately afterwards, so that he had missed most of his school-work. His headmaster had written to his uncle and aunt suggesting that he should go and stay at the home of one of the teachers for a few weeks, to make up a little of what he had missed. And, much to Philip’s disgust, his uncle had at once agreed – so there was Philip, in the summer holidays, having to work at algebra and geography and history, instead of having a fine time with his sister Dinah at his home, Craggy-Tops, by the sea.

He liked the master, Mr Roy, but he was bored with the other two boys there, who, also owing to illness, were being crammed or coached by Mr Roy. One was much older than Philip, and the other was a poor whining creature who was simply terrified of the various insects and animals that Philip always seemed to be collecting or rescuing. The boy was intensely fond of all creatures and had an amazing knack of making them trust him.

Now he hurried down the hillside, eager to see if another pupil had joined the little holiday collection of boys to be coached. If the new boy owned the parrot, he would be somebody interesting – more interesting than that big lout of a Sam, and better fun than poor whining Oliver.

He opened the garden gate and then stared in surprise. A girl was in the garden, not a very big girl – perhaps about eleven. She had red hair, rather curly, and green eyes, a fair skin and hundreds of freckles. She stared at Philip.

‘Hallo,’ said Philip, rather liking the look of the girl, who was dressed in shorts and a jersey. ‘Have you come here?’

‘Looks like it,’ said the girl, with a grin. ‘But I haven’t come to work. Only to be with Jack.’

‘Who’s Jack?’ asked Philip.

‘My brother,’ said the girl. ‘He’s got to be coached. You should have seen his report last term. He was bottom in everything. He’s very clever really, but he just doesn’t bother. He says he’s going to be an ornithologist, so what’s the good of learning dates and capes and poems and things?’

‘What’s an— an— whatever it was you said?’ said Philip, wondering how anyone could possibly have so many freckles on her nose as this girl had.

‘Ornithologist? Oh, it’s someone who loves and studies birds,’ said the girl. ‘Didn’t you know that? Jack’s mad on birds.’

‘He ought to come and live where I live then,’ said Philip at once. ‘I live on a very wild, lonely part of the sea-coast, and there are heaps of rare sea-birds there. I like birds too, but I don’t know much about them. I say – does that parrot belong to Jack?’

‘Yes,’ said the girl. ‘He’s had her for four years. Her name is Kiki.’

‘Did he teach it to say all those things?’ said Philip, thinking that though Jack might be bottom in all school subjects he would certainly get top marks for teaching parrots to talk!

‘Oh no,’ said the girl, smiling, so that her green eyes twinkled and crinkled. ‘Kiki just picked up those sayings of hers – picked them up from our old uncle, who is the crossest old man in the world, I should think. Our mother and father are dead, so Uncle Geoffrey has us in the hols, and doesn’t he just hate it! His housekeeper hates us too, so we don’t have much of a time, but so long as I have Jack, and so long as Jack has his beloved birds, we are happy enough.’

‘I suppose Jack got sent here to learn a few things, like me,’ said Philip. ‘You’ll be lucky – you’ll be able to play, go for walks, do what you like, whilst we are stewing in lessons.’

‘No, I shan’t,’ said the girl. ‘I shall be with Jack. I don’t have him in the school term, so I’m jolly well going to have him in the hols. I think he’s marvellous.’

‘Well, that’s more than my sister, Dinah, thinks of me,’ said Philip. ‘We’re always quarrelling. Hallo – is this Jack?’

A boy came up the path towards Philip. On his left shoulder sat the parrot, Kiki, rubbing her beak softly against Jack’s ear, and saying something in a low voice. The boy scratched the parrot’s head and gazed at Philip with the same green eyes as his sister had. His hair was even redder, and his face so freckled that it would have been impossible to find a clear space anywhere, for there seemed to be freckles on top of freckles.

‘Hallo, Freckles,’ said Philip, and grinned.

‘Hallo, Tufty,’ said Jack, and grinned too. Philip put up his hand and felt his front bit of hair, which always rose up in a sort of tuft. No amount of water and brushing would make it lie down for long.

‘Wipe your feet,’ said Kiki severely.

‘I’m glad you found Kiki all right,’ said the girl. ‘She didn’t like coming to a strange place, and that’s why she flew off, I expect.’

‘She wasn’t far away, Lucy-Ann,’ said Jack. ‘I bet old Tufty here got a fright if he heard her up on the hillside.’

‘I did,’ said Philip, and began telling the two what had happened. They laughed loudly, and Kiki joined in, cackling in a most human manner.

‘Golly, I’m glad you and Lucy-Ann have come here,’ said Philip, feeling much happier than he had felt for some days. He liked the look of the red-haired, green-eyed brother and sister very much. They would be friends. He would show them the animals he had as pets. They could go for walks together. Jack was some years older than Lucy-Ann, about fourteen, Philip thought, just a little older than he himself was. It was a pity Dinah wasn’t there too, then there would be four of them. Dinah was twelve. She would fit in nicely – only, perhaps, with her quick impatience and quarrelsome nature, it might not be peaceful!

‘How different Lucy-Ann and Jack are from me and Dinah,’ thought Philip. It was quite plain that Lucy-Ann adored Jack, and Philip could not imagine Dinah hanging on to his words, eager to do his bidding, fetching and carrying for him, as Lucy-Ann did for Jack.

‘Oh, well – people are different,’ thought the boy. ‘Dinah’s a good sort, even if we do quarrel and fight. She must be having a pretty awful time at Craggy-Tops without me. I bet Aunt Polly is working her hard.’

It was pleasant at tea-time that day to sit and watch Jack’s parrot on his shoulder, making remarks from time to time. It was good to see the glint in Lucy-Ann’s green eyes as she teased big, slow Sam, and ticked off the smaller, peevish Oliver. Things would liven up a bit now.

They certainly did. Holiday coaching was much more fun with Jack and Lucy-Ann there too.

2

Making friends

Mr Roy, the holiday master, worked the children hard, because that was his job. He coached them the whole of the morning, going over and over everything patiently, making sure it was understood, demanding, and usually getting, close attention.

At least he got it from everyone except Jack. Jack gave close attention to nothing unless it had feathers.

‘If you studied your geometry as closely as you study that book on birds, you’d be top of any class,’ complained Mr Roy. ‘You exasperate me, Jack Trent. You exasperate me more than I can say.’

‘Use your handkerchief,’ said the parrot impertinently.

Mr Roy made a clicking noise of annoyance with his tongue. ‘I shall wring that bird’s neck one day. What with you saying you can’t work unless Kiki is on your shoulder, and Philip harbouring all kinds of unpleasant creatures about his person, this holiday class is rapidly getting unbearable. The only one that appears to do any work at all is Lucy-Ann, and she hasn’t come here to work.’

Lucy-Ann liked work. She enjoyed sitting beside Jack, trying to do the same work as he had been se

t. Jack mooned over it, thinking of gannets and cormorants which he had just been reading about, whilst Lucy-Ann tried her hand at solving the problems set out in his book. She liked, too, watching Philip, because she never knew what animal or creature would walk out of his sleeve or collar or pocket. The day before, a very large and peculiarly coloured caterpillar had crawled from his sleeve, to Mr Roy’s intense annoyance. And that morning a young rat had left Philip’s sleeve on a journey of exploration and had gone up Mr Roy’s trouser-leg in a most determined manner.

This had upset the whole class for ten minutes whilst Mr Roy had tried to dislodge the rat. It was no wonder he was in a bad temper. He was usually a patient and amiable man, but two boys like Jack and Philip were disturbing to any class.

The mornings were always passed in hard work. The afternoons were given to preparation for the next day, and to the writing-out of answers on the morning’s work. The evenings were completely free. As there were only four boys to coach, Mr Roy could give them each individual attention, and try to fill in the gaps in their knowledge. Usually he was a most successful coach, but these holidays were not showing as much good work as he had hoped.

Sam, the big boy, was stupid and slow. Oliver was peevish, sorry for himself, and resented having to work at all. Jack was impossible, so inattentive at times that it seemed a waste of time to try and teach him. He seemed to think of nothing but birds. ‘If I grew feathers, he would probably do everything I told him,’ thought Mr Roy. ‘I never knew anyone so mad on birds before. I believe he knows the eggs of every bird in the world. He’s got good brains, but he won’t use them for anything that he’s not really interested in.’

Philip was the only boy who showed much improvement, though he was a trial too, with his different and peculiar pets. That rat! Mr Roy shuddered when he thought of how it had felt, climbing up his leg. Really, Lucy-Ann was the only one who worked properly, and she didn’t need to. She had only come because she would not be separated from her brother, Jack.