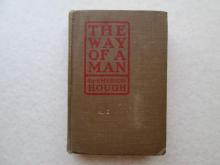

The Way of a Man

Emerson Hough

THE WAY OF A MAN

by

EMERSON HOUGH

Author of _The Covered Wagon_, etc.

Illustrated with Scenes from the Photoplay, _The Way of A Man_,A Pathe Picture

Grosset & DunlapPublishers New York

1907

GRACE SHOWS A LACK OF SYMPATHY.]

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I THE KISSING OF MISS GRACE SHERATON II THE MEETING OF GORDON ORME III THE ART OF THE ORIENT IV WARS AND RUMORS OF WAR V THE MADNESS OF MUCH KISSING VI A SAD LOVER VII WHAT COMETH IN THE NIGHT VIII BEGINNING ADVENTURES IN NEW LANDS IX THE GIRL WITH THE HEART X THE SUPREME COURT XI THE MORNING AFTER XII THE WRECK ON THE RIVER XIII THE FACE IN THE FIRELIGHT XIV AU LARGE XV HER INFINITE VARIETY XVI BUFFALO XVII SIOUX! XVIII THE TEST XIX THE QUALITY OF MERCY XX GORDON ORME, MAGICIAN XXI TWO IN THE DESERT XXII MANDY MCGOVERN ON MARRIAGE XXIII ISSUE JOINED XXIV FORSAKING ALL OTHERS XXV CLEAVING ONLY UNTO HER XXVI IN SICKNESS AND IN HEALTH XXVII WITH ALL MY WORLDLY GOODS I THEE ENDOW XXVIII TILL DEATH DO PART XXIX THE GARDEN XXX THEY TWAIN XXXI THE BETROTHAL XXXII THE COVENANT XXXIII THE FLAMING SWORD XXXIV THE LOSS OF PARADISE XXXV THE YOKE XXXVI THE GOAD XXXVII THE FURROWXXXVIII HEARTS HYPOTHECATED XXXIX THE UNCOVERING OF GORDON ORME XL A CONFUSION IN COVENANTS XLI ELLEN OR GRACE XLII FACE TO FACE XLIII THE RECKONING XLIV THIS INDENTURE WITNESSETH XLV ELLEN

CHAPTER I

THE KISSING OF MISS GRACE SHERATON

I admit I kissed her.

Perhaps I should not have done so. Perhaps I would not do so again. HadI known what was to come I could not have done so. Nevertheless I did.

After all, it was not strange. All things about us conspired to beaccessory and incendiary. The air of the Virginia morning was so softand warm, the honeysuckles along the wall were so languid sweet, thebees and the hollyhocks up to the walk so fat and lazy, the smell of theorchard was so rich, the south wind from the fields was so wanton!Moreover, I was only twenty-six. As it chances, I was this sort of aman: thick in the arm and neck, deep through, just short of six feettall, and wide as a door, my mother said; strong as one man out of athousand, my father said. And then--the girl was there.

So this was how it happened that I threw the reins of Satan, my blackhorse, over the hooked iron of the gate at Dixiana Farm and strode up tothe side of the stone pillar where Grace Sheraton stood, shading hereyes with her hand, watching me approach through the deep trough roadthat flattened there, near the Sheraton lane. So I laughed and strodeup--and kept my promise. I had promised myself that I would kiss her thefirst time that seemed feasible. I had even promised her--when she camehome from Philadelphia so lofty and superior for her stopping a brace ofyears with Miss Carey at her Allendale Academy for Young Ladies--that ifshe mitigated not something of her haughtiness, I would kiss her fair,as if she were but a girl of the country. Of these latter I may guiltilyconfess, though with no names, I had known many who rebelled little morethan formally.

She stood in the shade of the stone pillar, where the ivy made a deepgreen, and held back her light blue skirt daintily, in her high-bredway; for never was a girl Sheraton who was not high-bred or other thanfair to look upon in the Sheraton way--slender, rather tall, longcheeked, with very much dark hair and a deep color under the skin, andsomething of long curves withal. They were ladies, every one, theseSheraton girls; and as Miss Grace presently advised me, no milkmaidswandering and waiting in lanes for lovers.

When I sprang down from Satan Miss Grace was but a pace or so away. Iput out a hand on either side of her as she stood in the shade, and soprisoned her against the pillar. She flushed at this, and caught at myarm with both hands, which made me smile, for few men in that countrycould have put away my arms from the stone until I liked. Then I bentand kissed her fair, and took what revenge was due our girls for herPhiladelphia manners.

When she boxed my ears I kissed her once more. Had she not at thatsmiled at me a little, I should have been a boor, I admit. As shedid--and as I in my innocence supposed all girls did--I presume I may becalled but a man as men go. Miss Grace grew very rosy for a Sheraton,but her eyes were bright. So I threw my hat on the grass by the side ofthe gate and bowed her to be seated. We sat and looked up the lane whichwound on to the big Sheraton house, and up the red road which led fromtheir farm over toward our lands, the John Cowles farm, which had beenthree generations in our family as against four on the part of theSheratons' holdings; a fact which I think always ranked us in theSheraton soul a trifle lower than themselves.

We were neighbors, Miss Grace and I, and as I lazily looked out over thered road unoccupied at the time by even the wobbling wheel of somenegro's cart, I said to her some word of our being neighbors, and of itsbeing no sin for neighbors to exchange the courtesy of a greeting whenthey met upon such a morning. This seemed not to please her; indeed Iopine that the best way of a man with a maid is to make no manner ofspeech whatever before or after any such incident as this.

"I was just wandering down the lane," she said, "to see if Jerry hadfound my horse, Fanny."

"Old Jerry's a mile back up the road," said I, "fast asleep under thehedge."

"The black rascal!"

"He is my friend," said I, smiling.

"You do indeed take me for some common person," said she; "as though Ihad been looking for--"

"No, I take you only for the sweetest Sheraton that ever came to meet aCowles from the farm yonder." Which was coming rather close home, forour families, though neighbors, had once had trouble over some suchmeeting as this two generations back; though of that I do not now speak.

"Cannot a girl walk down her own carriage road of a morning, afterhollyhocks for the windows, without--"

"She cannot!" I answered. I would have put out an arm for furthermistreatment, but all at once I pulled up. What was I coming to, I, JohnCowles, this morning when the bees droned fat and the flowers madefragrant all the air? I was no boy, but a man grown; and ruthless as Iwas, I had all the breeding the land could give me, full Virginiatraining as to what a gentleman should be. And a gentleman, unless hemay travel all a road, does not set foot too far into it when he seesthat he is taken at what seems his wish. So now I said how glad I wasthat she had come back from school, though a fine lady now, and no doubtforgetful of her friends, of myself, who once caught young rabbits andbirds for her, and made pens for the little pink pigs at the orchardedge, and all of that. But she had no mind, it seemed to me, to talk ofthese old days; and though now some sort of wall seemed to me to arisebetween us as we sat there on the bank blowing at dandelions and pullingloose grass blades, and humming a bit of tune now and then as youngpersons will, still, thickheaded as I was, it was in some way madeapparent to me that I was quite as willing the wall should be there asshe herself was willing.

My mother had mentioned Miss Grace Sheraton to me before. My father hadnever opposed my riding over now and then to the Sheraton gates. Therewere no better families in our county than these two. There was noreason why I should feel troubled. Yet as I looked out into the haze ofthe hilltops where the red road appeared to leap off sheer to meet thedistant rim of the Blue Ridge, I seemed to hear some whispered warning.I was young, and wild as any deer in those hills beyond. Had it beenany enterprise scorning settled ways; had it been merely a breaking oforders and a following of my own will, I suppose I might have gone on.But there are ever two things which govern an adventure for one of mysex. He may be a man; but he must also be a gentleman. I suppose booksmight be written about the war between those two things. He may be agentleman sometimes and have credit for being a soft-headed fool, withno daring to approach the very woman who has contempt for

him; whereasshe may not know his reasons for restraint. So much for civilization,which at times I hated because it brought such problems. Yet theseproblems never cease, at least while youth lasts, and no community isfree from them, even so quiet a one as ours there in the valley of theold Blue Ridge, before the wars had rolled across it and made all theyoung people old.

I was of no mind to end my wildness and my roaming just yet; and still,seeing that I was, by gentleness of my Quaker mother and by sternness ofmy Virginia father, set in the class of gentlemen, I had no wishdishonorably to engage a woman's heart. Alas, I was not the first tolearn that kissing is a most difficult art to practice!

When one reflects, the matter seems most intricate. Life to the young isbarren without kissing; yet a kiss with too much warmth may meanovermuch, whereas a kiss with no warmth to it is not worth the pains.The kiss which comes precisely at the moment when it should, in quitesufficient warmth and yet not of complicating fervor, working no harmand but joy to both involved--those kisses, now that one pauses to thinkit over, are relatively few.

As for me, I thought it was time for me to be going.