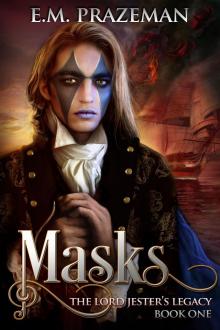

Masks

E.M. Prazeman

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty One

Chapter Twenty Two

Chapter Twenty Three

Chapter Twenty Four

Chapter Twenty Five

© 2011 Wyrd Goat Press

All Rights Reserved.

This work may not be reproduced in whole or any part in any form without the author’s permission. For permission and more information email [email protected].

Also available in print.

Cover art and design by Ravven

https://www.ravven.com

Chapter One

Mark guarded the moneybox at a small table beside his mother’s shrouded body. Butlers in dark overcoats, rich merchant’s sons dressed like lacy nobles and other regular patrons of his mother’s wine shop sorted through estate wares. Gray light outlined the shadowed people as they came in from the spring morning’s chill. Some perused the selection in the barrel room. Some touched Mark on the top of his head as they passed and whispered, “allolai protect you.” They stole bits of his composure and mussed his hair.

A tall, heavy-shouldered man came in. Mark looked hopefully, only to be disappointed.

His father had been missing for a whole day now.

Mark wormed his hand into the winding sheet and held his mother’s icy hand. Squeezed it. It didn’t feel like her anymore. More like raw poultry in a glove.

Thomas, one of the regulars, came over with his battered purse. “How about two gules for the two barrels of burgundy you have left.” His sweaty, dark-bearded face mounded into a smile.

Mark opened his mother’s ledger. She’d purchased the burgundy for two gules a barrel. The familiar lines of her tidy handwriting threatened to make his eyes tear up. He shut the ledger. “No.”

The smile smoothed away and Thomas leaned closer. “Come on, boy. That’s more than you’ve seen all day.”

Thomas’ forceful manner made his cheeks burn. Mark owned a certain fondness for him, but it felt too much like Thomas wanted to take advantage. “Make a better offer or leave off.”

“Here now,” Thomas said, reddening. “Your mother never treated a paying customer so! I wouldn’t cheat you. We’ve always been friendly, haven’t we, Mark?”

Thomas’ smile failed to disguise a glint of cold anticipation in his dark eyes. What did he really want? “They’re worth thrice more. And I can sell it by the carafe if I want.” His fears of losing everything his parents had worked for churned back up, though it wasn’t as bad as—

His mother had still been alive when he found her soaked in blood, gasping, unable to speak. He saw terror and pain in her eyes—

The bastard laughed. “By the carafe? The landlord won’t lease this place to a song boy. You have a day at most to make your money and run.”

Mark’s heart skipped. “Lord Jorbeth knows I helped keep the books. I’m old enough.” Older than the baker’s ten year old son, and that illiterate bully managed the store while his father slept all day. Mark’s face warmed as his temper rose. “And my father will turn up soon.”

“Take the money you have and run while you can.” The nastiness had left Thomas’ voice and his eyes widened with earnest. “I mean it, boy.” Was that real concern in his eyes? Thomas opened the purse and picked out two gules from a jumble of argen, cupru and bits. “Find me later. I know a place you can stay.”

A man like Thomas oughtn’t have that much coin.

“I can’t run,” Mark told him. “My father has an indenture and the only way I can pay on it is if I have the shop.”

“Never mind the indenture. I can protect you from the Church.”

Mark’s heart jumped. No one, well, maybe someone from the islands could protect him from the Church. But what did Thomas want with him, and why would Mark need protection?

The doors swung open and two priests strode in. Half red, half white robes billowed around them. Their absurd, black-winged hats were unexpectedly intimidating as the men towered over him. The younger priest carried two ledger books bound in black. He swept cork pullers and flatware off a table and opened his books to places marked by red ribbon. Dust billowed out from the pages.

The estate patrons shrank back into the shop corners to watch.

Lord Jorbeth followed the priests in. He looked anxious, his clean-shaven face pale against a black velvet coat and vest. Another lord came in after Jorbeth, a large, blond man that looked like he did more sailing than lording judging by his weathered face, braided hair and thick beard, though he wore finely-tailored clothes.

“This sale is closed,” the elder priest announced. “All funds and remaining property are being held by the Church.”

What? Heat rose up through Mark’s body, and then chill poured down.

Everyone set aside whatever they held and fled, snaking around the unmoving priests and lords. The elder priest watched carefully, like he expected thievery.

The coins dropped back into Thomas’ purse and he grabbed Mark by the arm. “Come along son.” He hurried toward the door with the others. The priest grabbed Mark by the other arm.

“What are you doing?” the priest asked sharply.

Thomas released Mark’s arm and smiled. “Taking the boy home.” He looked unafraid, even defiant.

The priest looked between them. “I think not.” His gaze settled on Mark, cold and ancient. “You are the heir?”

Thomas twitched his head, hinting at negation.

Mark stole courage from he didn’t know where. He’d rather tell the truth and make it on his own than trust Thomas, who probably had something other than charity in mind. “Yes.” His heart fluttered and he caught his breath as the priest’s grip tightened.

“Hand them over,” the priest said, shifting his gaze to Thomas.

“What, Your Wisdom?” Thomas’ tone made the words sound more sarcastic than respectful.

“The gules you offered the boy. Hand them over.”

“But I haven’t bought anything,” Thomas protested with a laugh.

“It’s true sir.” Mark realized his mistake in address when the priest lifted his chin with affront. “Your Wisdom. He offered but I didn’t—”

“You dare lie to me?” The priest glared at Mark.

“I’m not,” Mark protested.

The priest turned his attention back to Thomas. “The gules. Or do I need to speak with your lord on this matter?”

Lord? Perhaps he shouldn’t have been surprised that Thomas worked for a noble, considering his regular visits to buy good wine, but the fact that the priest seemed to know Thomas and was willing to take such a large sum from him without a qualm shocked him.

Thomas bowed his head and, much to Mark’s surprise, handed over the coin with a bold and unpleasant smile. “I’ll come back for my barrel of wine, and the rest of what’s mine.” Thomas surreptitiously looked back at Mark. He didn’t look upset, only like he wanted to make sure Mark understood that he should have left before the priests came. How had he known that they were coming?

Thomas went out into the street with purposeful haste. It seemed darker outside, as if a storm were coming.

The priest released Mark and pointed to a stool. Ma

rk sat, feeling as if he’d been robbed. He didn’t know how to get whatever it was he’d lost back again. He supposed it was kind of Thomas to lay claim to only one barrel of burgundy when he could have at least attempted to lay claim to two and, thanks to the priest’s lack of regard, would have probably gotten it.

The priest raised his hands and spoke foreign words. He sounded bored. He lowered his hands and walked over to Mark, looming over him. “You are their sole child?”

“Yes, Your Wisdom. Mark Seaton.” Mark didn’t know his place with a priest. He didn’t know the priest’s place here, either, unless it had to do with his indenture. Maybe he was a mavson, here to investigate. “Someone murdered my mother and my father is missing,” Mark told him. “The guard said—”

“When the murderer is caught he’ll be executed,” the priest said. “What should concern you now is your indenture.”

The words shouldn’t have made him afraid, but cold filled his belly just the same. “My father kept his indenture in good order, and until it’s proven that—” His father couldn’t be dead. “He could arrive at any time.”

“The mavson assigned to this case doubts that anyone will see your father again.”

“But it’s only been a day—”

“Perhaps if you were older you could manage on your own, but since you’re still a child the Church will manage this matter for you.” The priest turned his attention to Lord Jorbeth. “You said the table and chairs are part of your property.”

“Yes,” Jorbeth said. Too much white showed in his eyes. Mark’s stomach clenched up tight. “And the household furniture.”

The furniture? No.

“Show me,” the priest said.

They went upstairs. Mark gaped for a heartbeat before he followed after them. “My lord,” he protested, fighting back rage that choked his chest and throat, “my father still might come home and these are our things, you know they’re our things, things my father—”

“Hush. You don’t know the first thing about what your parents did and didn’t own. I do.” Lord Jorbeth leaned close. His breath smelled like cloves and sour wine. “I’m trying to save a few things for you, Mark,” he whispered. “Trust me. Now go downstairs and be silent.”

Mark stayed on the stairs while the landlord continued up. The priest moved heavily around their private rooms, his footfalls knocking dust from the ceiling. Trembling, Mark went back downstairs to his mother and took her cold hand again. He wished he dared look at her again, but the last time he’d pulled back the winding sheets her face had looked like a mask, cold and comfortless.

The other lord quietly watched Mark. He was a powerfully built and unhandsome man. “Your insolence will earn you a beating,” he said.

Mark lowered his gaze, his heart thundering in his ears.

The priest returned with Lord Jorbeth. The younger priest continued to write busily. “We will inventory the landlord’s possessions, and then we will sell the remainder to pay against the indenture, Lord Gillvrey,” the elder priest said.

Mark knew that name well. The thundering in Mark’s ears grew louder. He wished he mattered to this man that worked alongside his father.

Lord Gillvrey surveyed the room with disinterest. His gaze returned to Mark. “How much would the navy pay for the boy’s indenture?”

Mark blinked, not sure he’d heard right. The navy had lost so many ships in the war. Dozens had sailed from this very port, and not all of them returned. Did he want to send Mark to his death? “I can sail for you,” Mark promised. Everyone assumed he was too small, even his father, but he knew he could be a great sailor if someone just gave him a chance. “I would work hard for you, just as my father did. Please.”

“How old is he?” the older priest asked the younger one.

“Eleven,” Mark said, but the priest didn’t listen to him. Maybe eleven would be too young to get shot, or stabbed, too young to drown or be blown apart by cannons. He’d always wanted to sail, but not to war.

The younger priest paged back in one of the ledger books and peered down his nose through his glasses. “Eleven years, five months.”

The priest spared Mark a glance. “Looks younger. Still, old enough to serve in the navy.”

Lord Jorbeth cleared his throat. He looked at Mark, half-appraising, half-apologetic. “I’ll pay thirty gules.”

Thirty gules. He never thought to be worth so much, and at the same time it seemed a mean amount for a person’s life.

Gillvrey sniffed again. “I’m certain the king pays more than that.”

Anger and terror mixed him up inside, but Mark managed to open his mouth and the words escaped. “If I’m dead I’m not worth anything. Or is a corpse worth something, my lord?”

“The last figure I heard was fifty gules for a sailor of less than fourteen years,” the priest said, ignoring Mark. The priest writing at the table lifted his pen and nodded in agreement before he set to writing again. “The boy could do well more than fifty gules worth of work for you in his lifetime, Lord Gillvrey. It might be a better bargain to keep him than sell him to the navy.”

“He’s frail boy.” Lord Gillvrey shifted his attention to stare at Mark. “Trade shipping is for strong men.”

Mark found his voice, and his mind again. “I read, write, and I know enough arithmetic to keep books. And I am my father’s son. I’ll grow into my height in time.” He couldn’t believe he was trying to sell himself. “My lord, why am I being sold? My father held this indenture for longer than I’ve been alive and has never missed a payment. Can’t you wait until the end of the month at least?”

“Your family owes two hundred fifty gules before it earns out for the Swift-by, so don’t pretend the ship has anything to do with you aside from a distant dream,” Lord Gillvrey said. “What matters now is that you wouldn’t manage on that ship, and I have no use for you on land.”

“That doesn’t erase my father’s payments.” Mark looked to the priests. “If he’s trying to buy the ship then what my family earned is owed back.” He’d dreamed of owning the Swift-by, but if he couldn’t, at least he wouldn’t see it stolen through political conniving.

The priest crossed his arms, annoyed. “Lord Gillvrey is not in fact buying the ship, nor is such a thing possible while you live. He merely holds the trust for your family’s indenture. Since he has no use for you and you are too young to carry an indenture by yourself, the Church is taking legal guardianship and will assign the most profitable work we can find for you until you come of age, at which point the indenture might be renegotiated if you so demand. I understand if you’re afraid to go to war, young man, but bear in mind that you might distinguish yourself, and that you might win a share of a prize that will earn out the indenture in entire. Then you’ll have a ship of your own.”

As if he would survive to see it. “Why can’t I work here?”

“Because you won’t be able to turn a profit here. No one will do serious business with you. You couldn’t keep up the lease payments, never mind pay against your indenture.”

Mark’s chest contracted. “So you intend to send me to the navy? Who gets the indenture if I die? The Church?”

The priest’s eyes flashed with anger. “You dare imply that the Church would deliberately profit from your death?”

Mark lowered his gaze and his voice. “Please, I just want to understand.”

The priest relented. “If you default and have no near relatives who wish to claim it, the balance of the indenture goes to auction, a thing that I’m sure Lord Gillvrey wishes to avoid since I doubt he would compete well in an auction. Ships are in high demand at the moment. The guarantor will indeed be the Church, with a certain amount going to the Crown. There are other details related to the hull fund—it’s complicated.”

“So complicated that you haven’t the time, or is it that you don’t have the ability to explain it?” Mark’s voice shook and his face burned with anger and his hands trembled and there was nothing he could do.

Default. He made death sound like a hatch mark on a piece of paper. “I would rather auction off the indenture now than to be sold like a slave to the navy.”

The priest looked over his glasses at Mark. “That would be very foolish. Anyway, you’re too young to decide for yourself.”

Mark wanted to scream the words but his voice choked them into a broken protest. “I thought slavery was a sin, your wisdom, but it seems it isn’t if the Church oversees the selling.”

“Stupid boy,” the priest spat. “The Church is your only ally now. Best you be silent and thankful the Church is looking after you through me.”

Lord Gillvrey crossed his arms and smiled smugly. “Is there anyone else who might be interested in offering the boy gainful employment?”

Lord Jorbeth leaned against the bar and put his head in his hand like it hurt. Mark looked toward the door and wondered if he ought to run, and if he ran, if he could find Thomas before the sacred guardsmen caught up with him.

“The Church—” The priest paused as a carriage, pulled by many horses, rattled up the street. Mark expected it to keep going, but it stopped. “The Church can set a modest wage and put the boy to work at civic duties until there is a more satisfactory offer, but if those who know him don’t want him, it’s unlikely a stranger will make a better offer.”

The door opened and yet another lord came in, a wrinkled man of average height, gray hair cut short and bound into a short tail in a lush velvet ribbon. Silks and brocades shone under a mink cloak lined with velvet. He had small eyes, a small nose and a large mouth that made Mark think of a fish. Behind him, a jester leaned casually in the doorway.

Mark’s gaze locked on the jester. He wore a black porcelain demi-mask covered in a complex gold design enhanced with sapphires and blue diamonds. The jester’s black clothes sparkled with sapphires as well. He had weight to him but he balanced with terrible grace, his hand resting on a glittering rapier. An elegant dueling pistol rested on his other hip in easy reach.

His clothes alone could have bought Mark’s indenture several times over.

The priests straightened, chins lifting, and the priest doing the writing bared his teeth at the jester. For a moment they all stood in poses like a tableau for a tragedy.

The old lord’s gaze fell on Mark with expectation that seemed braced for disappointment. He looked Mark over, and his expression lightened. “Interesting find.”

“My Lord Argenwain,” the priest said tightly, “we are in the midst of a legal proceeding.”

The name nearly stopped Mark’s heart. Argenwain, head patron of Seven Churches and a great personal friend to His Royal Majesty King Michael. Which meant the jester was Gutter, favorite of the king.

“My lord my lord.” Gutter laughed, moving past Mark’s mother to sidle around the priest. “We are here for the sale. The boy is for sale, isn’t he? And I’ve brought a buyer.”

“He’s not a slave,” the priest informed Gutter. “He is renegotiating a contractual indenture—”

Gutter chuckled. “Does that increase or decrease the price?”

“I had no idea Lord Argenwain was interested in carrying a contractual indenture for an insignificant commoner,” the priest said again, his tongue cutting the words into tight syllables.

Gutter turned his attention to Lord Argenwain. “You can trust me about his voice, my lord. At the moment he probably couldn’t hold a note if I put it in his hand, poor boy, shook up by all this legal rape, otherwise I’d have him sing us some cheer.”

At any other time, Mark might have blushed with shy pride, but instead a fearful cold grabbed his spine in its teeth.

Lord Argenwain looked Mark over again. “What is the rate?”

“A sol and I’ll give him up,” Lord Gillvrey said.

The amount stole Mark’s breath. Only the highest nobility traded in sols, the equivalent of one hundred gules. He wanted to run, to hit something, to hide. Instead he lifted his chin and swallowed his fear. “Maybe you should have asked for double. Then they’d be doubly sure not to take it.”

Gutter circled Lord Gillvrey like a lady circling her partner in a dance, an uncomfortably sensual and predatory movement that made Mark blush and shiver at the same time. “One sol. Is that all?” Gutter asked.

“A sol is nothing to sniff at.” Lord Gillvrey’s shoulders jogged briefly. “But I suppose the sum means little to you. He’s yours, if you want him.”

Mark had to sit. Lord Jester Gutter, the most notorious jester in the three kingdoms, was in his mother’s wine shop to buy him. His romantic daydreams about clever, playful jesters shattered into a reality that filled him with awe, like watching a storm toy with the huge ships in the harbor.

He wished he had that kind of power, even though he quaked in its presence.

Lord Jester Gutter approached the priest. “What would it take to hold the boy’s indenture outright?”

The priest glanced at Gillvrey, who shook his head. Jorbeth watched all this with an expression of quiet horror. “Two hundred forty seven gules buys the boy’s indenture and use of the Swift-by, a large trade ship,” the priest said. Gillvrey’s mouth opened in protest, but he didn’t make a sound and shut it again.

Almost two and a half sol. Mother and father together could have eventually paid it, but by myself ....

You are worth more than this. The strange voices that had haunted his mind since his earliest memories, sometimes friendly, sometimes disturbing, spoke in a foreign language but he’d always been able to understand them.

This one, the one Mark called Ruby, had spoken directly to him when his mother died too. Both times Ruby had failed to comfort him.

Meanwhile Lord Argenwain’s eyes had brightened and he looked to his jester with a bemused expression. “Trade ship? I’ve always been interested in ships.”

Maybe all they’d wanted was the ship all along, but they’d called Mark a find.

“I don’t intend to sell the whole indenture,” Gillvrey protested. “I inherited it from my father and I won’t give it up.”

Lord Jester Gutter’s eyes smiled behind the mask. “And why would you? Except.” Gutter’s hand caressed the swept hilt of his rapier. “I think it would be a mistake to hold your remaining interest in the ship, my lord. Trade is such a volatile thing during war. The risks are so much higher than in peacetime. If something happened to that ship, wouldn’t you have rather sold the use of it while you could?”

Gillvrey looked down at the jester’s jeweled boot buckles. “I’m willing to take on that risk. My family always has. We are in shipping, after all.”

“And I imagine it’s a good, fast ship,” Lord Jester Gutter said. He stepped precisely heel toe, heel toe, making staccato beats on the worn floor. “Something the military might be interested in commandeering, especially after their recent naval disaster.”

“It’s unsuitable for naval action.”

“I think a certain commander I’m acquainted with would disagree. But even if he decides it isn’t worthy for naval action, as you say, I think you’ll have trouble hiring cargo. Merchant lords, fearing pirates, are hearing from knowledgeable sources that it’s better to send as much of their wares overland as possible, for the time being.”

“Those who deal with me trust my judgment.” Gillvrey hissed, his breath coming hard.

Gutter leaned against the bar beside Gillvrey. “If that ship isn’t suitable to employ in a war as you say, it’s highly unlikely anyone would be willing to ship cargo on such a defenseless vessel.”

Gillvrey made a sad attempt to compose himself. Every movement Gutter made reminded Mark of theater, and Gillvrey appeared to be doomed to tragedy. “Are you threatening to undermine my business?” Gillvrey asked.

Lord Argenwain chuckled. The papery sound made Mark shiver. “No, no, of

course not. I would never condone such a thing.” Gutter laughed as if his lord had made a joke.

Lord Gillvrey looked to the priest. “You must do something. My interests are at stake here. This is my property.”

No, thought Mark. It’s mine. “If my parents were safe, you’d still have it, too. I guess this is your tragedy as well as mine, my lord.” Mark willed every word to stab, wished he could see the lord bleed for it.

“They’re not doing anything illegal,” the priest said. His gaze met Lord Argenwain’s, and it looked like the two of them had just made a silent pact.

“Why are you doing this?” Gillvrey demanded.

“Because my master wants it.” Lord Jester Gutter’s eyes behind the mask became darker and seemed to open into deep places, terrifying in their chill. Mark didn’t want to be at his mercy, but better to be in his service than dying at sea. “What was your name again, my lord?” Gutter asked. “If you choose to keep the ship I certainly will put in a word with merchants in every friendly country. I’ll encourage them to do the right thing by you, and I’m sure they’ll listen carefully to my advice.”

Gillvrey’s shoulders sank. Lord Jester Gutter’s eyes smiled again and he faced the priests. “Sold, for two hundred forty seven gules.”

“Less the sale price of the wine shop’s contents,” the eldest priest said. “As those are technically part of the boy’s inheritance.”

The jester glanced around the room. “I’ll send the butler to purchase the best of it tomorrow. Can we take the boy tonight?”

“His contract must be completed first,” the scribbling priest protested from his table.

“And in the meantime he has to stay in a cell at the church?” Gutter scoffed. “Ridiculous. Let us feed and shelter him and spare the Church the trouble and expense.”

Food and shelter. Those things seemed unimportant compared to his mother’s body growing colder and thinner every moment.

His father might arrive at any time, and Mark would not be here.

The old priest gave Mark a look that might have been gentle on a younger, less stern face. “Take him, then, and beware the wrath of morbai for your wicked ways, jester.”

Gutter laughed even as Mark shuddered. He walked to Mark and gestured toward the door. “It’s all right, Mark. You’ll have a better life this way. And someday, you might own that ship.”

Earn out that mighty sum before his life ran out? Mark looked back at the tables where his mother lay. He noticed a stain on the white winding sheet, dark reddish brown, in her body’s shadow. That rich, ugly color reached across the room like a disgusting odor, making him gag. “But what if my father comes back?” Mark asked. The priests just stared at him coldly, so Mark turned to Gutter. “My lord jester, please, my father might come back any moment.”

“Then the matter will go to court.” In that moment, Gutter’s voice sounded very kind, and gentle, and apologetic. Mark thirsted for that compassion almost as much as his mother’s love.

“Can’t we wait?” he pleaded.

“Such things are best handled promptly,” the older priest said.

“I’m sorry.” Gutter’s voice hushed down to a whisper.

He wanted to run up to his room, hide in his bed among his things and wait for his parents to come back somehow. No matter how good this chance, all he really wanted was to be home. “Will someone tell my father where I am, should he come home? And what will happen to the indenture if he does?”

Lord Jester Gutter crouched before him, earnest eyes peering through the mask. “Mark, you should have listened before. You have a second chance to listen to me now. Walk away from your old life, and never look back. I know it hurts, but I promise things will get better.” He pulled out a battered purse. Thomas’s battered purse. It was filled with gold. “You will make handsome wages as a servant in my lord’s house, more than your parents together. And I’m sure Lord Argenwain will make some fair arrangement with your father in regard to the indenture. With the Church’s oversight, of course.”

Thomas—it couldn’t be. A jester had been coming to his mother’s shop for years. Why? To buy wine and to trade oranges and chocolates for a song from her son?

It makes no sense.

“You’ve been watching me,” Mark said.

The jester smiled. “You’re a smart boy.” Thomas, Lord Jester Gutter, straightened. “It’s time to begin a life that will employ your intelligence and talent to its full.”

Lord Argenwain got a wistful, almost sad look. “He’s so young.”

“He’ll grow, my lord.” Gutter’s voice, though gentle, also held a sad note in it.

Lord Argenwain held out his hand. Though Mark had never dreamt of jewels and sleeping in soft rooms, those images tumbled into his mind. The old lord watched him with guileless eyes, gentle and inviting. An instinct he couldn’t name warned him that something was wrong, but better to face that unknown than war.

Under the priests’ sharp gazes Mark walked to Lord Argenwain and took his hand. Like his mother’s hand it was cold, but it squeezed and held him, and led him to the golden carriage waiting outside.