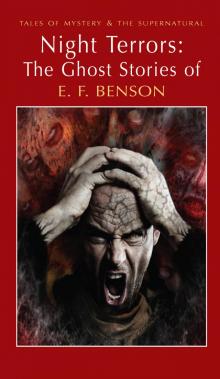

Night Terrors

E. F. Benson

Night Terrors

The Ghost Stories of E. F. Benson

with an Introduction by

David Stuart Davies

Night Terrors first published by

Wordsworth Editions Limited in 2012

Published as an ePublication 2012

ISBN 978 1 84870 311 7

Wordsworth Editions Limited

8B East Street, Ware, Hertfordshire SG12 9HJ

Wordsworth® is a registered trademark of

Wordsworth Editions Limited

Wordsworth Editions

is the company founded in 1987 by

MICHAEL TRAYLER

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Readers interested in other titles from Wordsworth Editions are invited to visit our website at

www.wordsworth-editions.com

For our latest list of printed books, and a full mail-order service contact

Bibliophile Books, Unit 5 Datapoint,

South Crescent, London E16 4TL

Tel: +44 020 74 74 24 74

Fax: +44 020 74 74 85 89

[email protected]

www.bibliophilebooks.com

For my husband

ANTHONY JOHN RANSON

with love from your wife, the publisher

Eternally grateful for your

unconditional love

Introduction

It is not given to many writers to find fame and success in two very different literary genres, but that is what Edward Frederic Benson achieved. He wrote over a hundred books in his lifetime, including his extremely successful social satires, the Mapp and Lucia novels. It is probably for these excursions into stylised comedy that he is best remembered today, helped by the very popular television series based on the books which was screened on Channel Four in the 1980s. However, it was for his ghost stories that E. F. Benson was best known during his lifetime. Even within this narrow category of fiction, Benson was able to range widely in both style and focus. In some respects variety was the key to his success, creating tales that featured vampires, homicidal spirits, monstrous spectral worms and slugs and other entities of nameless dread, while at times wearing his satirical hat and having a comic dig at charlatan mediums. His range was far broader and more adventurous than any other writer of supernatural fiction.

Benson came from a literary family which endured dramatic upheavals worthy of a gothic drama. His father Edward White Benson began his working life as a schoolmaster at Rugby school, but later entered the church, eventually ascending to the post of Archbishop of Canterbury. He married his bride Mary Sedgwick when she was just eighteen. They had six children in all, two of whom died in childbirth. The three male survivors, Arthur Christopher (1862–1925), Edward Frederic (1867–1940), Robert Hugh (1871–1914) all achieved status as respected authors, while their sister, Margaret (1865–1916) became a noted Egyptologist. For the young Bensons, the family circle was literally a hive of intellectual activity presided over by the father, who took advantage of virtually every free moment for the improvement of his children’s minds and to further some aspect of their education. A standing joke was made later about the need for a family publishing house in order to accommodate the works of the prolific Bensons.

However, E. F. Benson’s family background was far from idyllic. Strained would be a more apt epithet. His mother was hideously browbeaten by her formidable husband and after his death she changed her name to Ben and cohabited with a female friend. Earlier, Benson’s disturbed sister had attacked her mother and as a result had to be kept under restraint thereafter. His brothers were neurotic and difficult. On one occasion, young Arthur wrote ‘I hate Papa’ on a piece of paper and buried it in the garden.

The stress and the tension of familial upheaval seems to have provided E. F. Benson with several springboards for his imaginative writing and to have put him off marriage and family life for good. He never married or indeed formed any strong relationship through his life and in his autobiographical novel of schooldays, David Blaize (1916), Benson wrote, concerning the subject of sex, that to Blaize, ‘The whole matter was vague and repugnant to him, and he did not want to hear or know more.’ This attitude is reflected in Benson’s ghost stories. Sex is either unspoken or leads to trouble.

It was with a frivolous society novel, Dodo (1893), that Benson first achieved fame. It was so successful that he was able to devote

his whole life to writing. While the frivolous world of mannered society – in which he was a real life participant – featured in many

of his novels, it was the more seductive and unnerving tales of

the supernatural which were his first and abiding love. As this volume bears witness, throughout his life he never seemed to tire

of the desire to tingle the reader’s spine and make the hair rise on the back of the neck.

In many ways Benson was a disciple of the master of the ghost story – M. R. James. He knew James well and indeed he was a mem-

ber of the Chitchat Club, the Cambridge University literary society where James would read his tales of unease by candlelight to the chosen few. Benson was present at the historic meeting on 28 October 1893 when James read his first two ghost stories, ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook’ and ‘Lost Hearts’. These must have had a tremendous impact on Benson and it is not too fanciful to say

that in creating a series of ghost stories throughout his life Benson was trying to capture the chill and frisson of terror imbued in James’ work. Both men approached the genre with the same goal in mind: they seemed to agree that the most successful ghosts and elementals in supernatural fiction should be both malevolent and terrifying. However, it has to be said that Benson’s work is less measured and erudite and more dramatic, yet with a more refined construction.

In his autobiography, Final Edition (1940), Benson stated:

‘Ghost stories are a branch of literature at which I have often tried my hand. By a selection of disturbing details, it is not very difficult to induce in the reader an uneasy frame of mind which, carefully worked up, paves the way for terror. The narrator, I think, must succeed in frightening himself before he can think of frightening his readers . . . ’

More than James, Benson could be quite graphic in his descriptions, especially when dealing with non-human entities such as the slug-like elementals in ‘The Thing in the Hall’ and ‘Negotium Perambulams’. The latter is a tale in which the villain of the piece is reduced ‘to

no more than a rind of skin . . . over projecting bones’. There are also the yellowish grey caterpillars, the physical manifestation of cancer, which stalk an Italian villa in ‘Caterpillars’. Similarly Benson aims at the visceral chill with ‘The Step’, whose terrifying phantom had a face which is ‘a slab of smooth yellowish flesh’.

Benson’s stories reflected both his life and his proclivities. Almost all his narrators are single men with no real base who encounter ghosts and monsters in their ramblings. This was also a feature of the stories of M. R. James, another life-long bachelor. Benson’s heroes tend to have a fascination and at times a passion for old houses, ancient piles which contain secrets from the past that impinge unpleasantly on the present. ‘Bagnell Terrace’ is a case in point. The narrator, an inhabitant of Bagnell Terrace, envies the house at the apex of the cul-de-sac, owned by a mysterious gentleman whom ‘because of my desire for his house, we called Naboth’. When the house suddenly becomes vacant, the narrator is quick to acquire it. He then begins to experience strange happenings which not

only have resonances with the past but also ‘mysterious Egyptian cults, of which the force survived’, and was seen and felt in this quiet terrace. A similar theme is presented in ‘Naboth’s Vineyard’. (There’s that name again. Naboth is a Biblical character, the owner of a vineyard, which is coveted by King Ahab, but Naboth would not sell it to him and thus he becomes a symbol of envy and the unattainable.) In this story blackmail is used by the central character to obtain his desired residence. This is Ralph Hatchard, another bachelor, who ‘had little opinion of women as companions’. His triumph in securing the house of his dreams is short-lived. ‘Naboth’s Vineyard’ also gives

us another of Benson’s recurring themes: the limping ghost. He features most strongly in ‘A Tale of an Empty House’. The writer Joan Aiken, an advocate of Benson’s work, stated that she believed the limping man was a manifestation of Benson’s father. But, she added, ‘peel off yet another layer, and I believe the lame man is revealed as the writer himself. At the end of his life – Benson was obliged to walk with the aid of two sticks; this must have been a particularly penitential affliction for a man who had thrown himself into so many different kind of sport – golf, squash, tennis, swimming, skiing – with so much enthusiasm; it must have seemed like unfair and savage retribution.’ Ms Aiken never clearly explains the reason or cause for this ‘savage retribution’.

With the preponderance of middle-aged, anti-female single men taking the role of narrator in so many of Benson’s narratives, it is no surprise, then, that women rarely feature as the central characters in these ghost stories and when they do their role is both sinister and ominous. Perhaps the best example of this is ‘Mrs Amworth’ who, our bachelor narrator informs us, seems a cheerful soul with

a loud jolly laugh, but we discover that she is in fact a particularly nasty vampire who has a penchant for adolescent boys.

Other wicked ladies are found in ‘The Sanctuary’, again involving the corruption of youth; ‘The Corner House’ featuring the murderous Mrs Labson who nags her husband to death; and ‘The Bath-Chair’ in which Alice Faraday conspires with another limping spirit to create some unpleasantness for her brother.

Usually, when Benson’s men are married, the circumstances are blighted as in ‘Christopher Comes Back’, which is an unpleasant little story of marital murder and ghostly revenge. It almost takes the form of warning to the reader to beware of women – they will only bring trouble.

There isn’t space here to refer to every story in this fat and fabulous collection – and it is not appropriate to do so either but I would like to mention four stories of particular note.

‘The Face’ is perhaps the most unusual of Benson’s stories and is one of the most frightening. Its tone is modern and surreal. The writing is particularly vivid – filmic almost – and presents a tone and quality that was to inspire and be captured by several post-

war ghost story writers such as David G. Rowlands. At the heart

of this story is a recurring dream and throughout Benson’s prose has a chilling nightmarish quality that grips the reader. We travel with the central character deep into the dreamlike landscape, which is presented as though it were a moving mezzotint, graced with unfathomable shadows. Benson here has the facility to allow us to experience in some depth the strangeness and growing threat of these troubled dreams. Bravely, and rather satisfyingly, he does

not present an explanation for this persecuted haunting, which makes the resulting dénouement all the more dramatic and tragic. Unusually for Benson, the central character – one might almost say victim – is a pretty, young happily married woman whose life is idyllic until the shadow falls across her charmed existence. ‘The Face’ is a tale that haunts the reader long after he has reached the final sentence. It is one of Benson’s finest works.

‘Pirates’ is a personal ghost story. It is highly autobiographical and extremely subtle. The setting is a Cornish country house near Truro, based on Benson’s own childhood home when his father was Bishop of Truro. The plot concerns the sole survivor of five children who in later life purchases the old house in which he grew up and restores it in an attempt to somehow capture the past and his youthful happiness. He dies imagining himself back there as a young boy with his siblings. The title of the story refers to a game that Benson used to play as child with the entire family in the garden.

The third story of particular note is ‘How Fear Departed from the Long Gallery’, which concerns a pair of children, murdered in the seventeenth century, who haunt a country house. It means almost certain death to all those who catch sight of these spirits but, through the power of one individual’s sympathy and love, their fatal powers are finally eroded. It is an unusual ghost story with a comparatively happy ending and it was E. F. Benson’s favourite from all the tales he ever wrote.

Finally, mention should be made ‘The Bus-Conductor’. This is a deceptively simple tale but because of its inclusion in the masterful portmanteau horror film of the forties, the classic Dead of Night, it has achieved a certain celebrity. Even those who have not read the story will most likely have heard the chilling catchphrase uttered by the eponymous character: ‘Just room for one inside, sir.’ The story exemplifies much of what is typical and satisfying about Benson’s ghost stories: they are clearly, even at times simply, told tales which end with a chilling revelation – sometimes it is horrific, sometimes unnerving and sometimes very surprising, but always effective. The range and scope of these narratives guarantees that there can be

no sense of predictability or déja vu when reading a ghost story by

E. F. Benson. This certainly isn’t a collection to be picked at – but devoured greedily.

David Stuart Davies

Night Terrors

These stories have been written in the hopes of giving some pleasant qualms to their reader, so that, if by chance, anyone may be occupying in their perusal a leisure half-hour before he goes to bed when the night and house are still, he may perhaps cast an occasional glance into the corners and dark places of the room where he sits, to make sure that nothing unusual lurks in the shadow. For this is the avowed object of ghost-stories and such tales as deal with the dim unseen forces which occasionally and perturbingly make themselves manifest. The author therefore fervently wishes his readers a few uncomfortable moments.

E. F. Benson

The Room in the Tower

It is probable that everybody who is at all a constant dreamer has had at least one experience of an event or a sequence of circumstances which have come to his mind in sleep being subsequently realised in the material world. But, in my opinion, so far from this being a strange thing, it would be far odder if this fulfilment did not occasionally happen, since our dreams are, as a rule, concerned with people whom we know and places with which we are familiar, such as might very naturally occur in the awake and daylit world. True, these dreams are often broken into by some absurd and fantastic incident, which puts them out of court in regard to their subsequent fulfilment, but on the mere calculation of chances, it does not appear in the least unlikely that a dream imagined by anyone who dreams constantly should occasionally come true. Not long ago, for instance, I experienced such a fulfilment of a dream which seems to me in no way remarkable and to have no kind of psychical significance. The manner of it was as follows.

A certain friend of mine, living abroad, is amiable enough to write to me about once in a fortnight. Thus, when fourteen days or thereabouts have elapsed since I last heard from him, my mind, probably, either consciously or subconsciously, is expectant of a letter from him. One night last week I dreamed that as I was going upstairs to dress for dinner I heard, as I often heard, the sound of the postman’s knock on my front door, and diverted my direction downstairs instead. There, among other correspondence, was a letter from him. Thereafter the fantastic entered, for on opening it I found inside the ace of diamonds, and scribbled across it in his well-known handwriting, ‘I am s

ending you this for safe custody, as you know it is running an unreasonable risk to keep aces in Italy.’ The next evening I was just preparing to go upstairs to dress when I heard the postman’s knock, and did precisely as I had done in my dream. There, among other letters, was one from my friend. Only it did not contain the ace of diamonds. Had it done so, I should have attached more weight to the matter, which, as it stands, seems to me a perfectly ordinary coincidence. No doubt I consciously or subconsciously expected a letter from him, and this suggested to me my dream. Similarly, the fact that my friend had not written to me for a fortnight suggested to him that he should do so. But occasionally it is not so easy to find such an explanation, and for the following story I can find no explanation at all. It came out of the dark, and into the dark it has gone again.

All my life I have been a habitual dreamer: the nights are few, that is to say, when I do not find on awaking in the morning that some mental experience has been mine, and sometimes, all night long, apparently, a series of the most dazzling adventures befall me. Almost without exception these adventures are pleasant, though often merely trivial. It is of an exception that I am going to speak.

It was when I was about sixteen that a certain dream first came to me, and this is how it befell. It opened with my being set down at the door of a big red-brick house, where, I understood, I was going to stay. The servant who opened the door told me that tea was being served in the garden, and led me through a low dark-panelled hall, with a large open fireplace, on to a cheerful green lawn set round with flower beds. There were grouped about the tea-table a small party of people, but they were all strangers to me except one, who was a schoolfellow called Jack Stone, clearly the son of the house, and he introduced me to his mother and father and a couple of sisters. I was, I remember, somewhat astonished to find myself here, for the boy in question was scarcely known to me, and I rather disliked what I knew of him; moreover, he had left school nearly a year before. The afternoon was very hot, and an intolerable oppression reigned. On the far side of the lawn ran a red-brick wall, with an iron gate in its center, outside which stood a walnut tree. We sat in the shadow of the house opposite a row of long windows, inside which I could see a table with cloth laid, glimmering with glass and silver. This garden front of the house was very long, and at one end of it stood a tower of three storeys, which looked to me much older than the rest of the building.