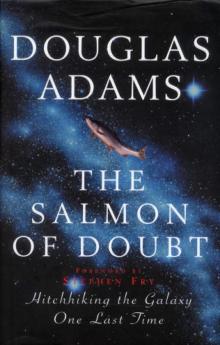

The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time dg-3

Douglas Adams

The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time

( Dirk Gently - 3 )

Douglas Adams

On Friday, May 11, 2001, the world mourned the untimely passing of Douglas Adams, beloved creator of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, dead of a heart attack at age forty-nine. Thankfully, in addition to a magnificent literary legacy—which includes seven novels and three co-authored works of nonfiction—Douglas left us something more. The book you are about to enjoy was rescued from his four computers, culled from an archive of chapters from his long-awaited novel-in-progress, as well as his short stories, speeches, articles, interviews, and letters.

In a way that none of his previous books could, The Salmon of Doubt provides the full, dazzling, laugh-out-loud experience of a journey through the galaxy as perceived by Douglas Adams. From a boy’s first love letter (to his favorite science fiction magazine) to the distinction of possessing a nose of heroic proportions; from climbing Kilimanjaro in a rhino costume to explaining why Americans can’t make a decent cup of tea; from lyrical tributes to the sublime pleasures found in music by Procol Harum, the Beatles, and Bach to the follies of his hopeless infatuation with technology; from fantastic, fictional forays into the private life of Genghis Khan to extended visits with Dirk Gently and Zaphod Beeblebrox: this is the vista from the elevated perch of one of the tallest, funniest, most brilliant, and most penetrating social critics and thinkers of our time.

Welcome to the wonderful mind of Douglas Adams.

Douglas Adams

The Salmon of Doubt

For Polly

Editor’s note

I first met Douglas Adams in 1990. Newly appointed his editor at Harmony Books, I had flown to London in search of Douglas’s long-overdue fifth Hitchhiker novel, Mostly Harmless. No sooner was I buzzed in the door to the Adams residence in Islington than a large, ebullient man bounded down the long staircase, greeted me warmly, and thrust a handful of pages at me. “See what you think of these,” he said over his shoulder as he bounded back up the stairs. An hour later he was back, new pages in hand, eager to hear my opinion of the first batch. And so the afternoon passed, quiet stretches of reading alternating with more bounding, more conversation, and fresh pages. This, it turned out, was Douglas’s favorite way of working.

In September 2001, four months after Douglas’s tragic, unexpected death, I received a phone call from his agent, Ed Victor. A good friend had preserved the contents of Douglas’s many beloved Macintosh computers; would I be interested in combing through the files to see if they contained the makings of a book? A few days later a package arrived, and, curiosity whetted, I tore it open.

My first thought was that Douglas’s friend, Chris Ogle, had undertaken a Herculean task—which, as it turned out, he had. The CD-ROM onto which Douglas’s writing had been collected contained 2,579 items, ranging from huge files that stored the complete text of Douglas’s books to letters on behalf of “Save the Rhino,” a favorite charity. Here, too, were fascinating glimpses into dozens of half-brewed ideas for books, films, and television programs, some as brief as a sentence or two, others running to half-a-dozen pages. Alongside these were drafts of speeches, pieces Douglas had written for his website, introductions to various books and events, and musings on subjects near to Douglas’s heart: music, technology, science, endangered species, travel, and single-malt whisky (to name just a few). Finally, I found dozens of versions of the new novel Douglas had been wrestling with for the better part of the past decade. Sorting these out to arrive at the work-in-progress you’ll find in the third section of this book would prove my greatest challenge, although that makes it sound difficult. It was not. As quickly as questions arose they seemed to answer themselves.

Conceived as a third Dirk Gently novel, Douglas’s novel-in-progress began life as A Spoon Too Short, and was described as such in his files until August 1993. From this point forward, folders refer to the novel as The Salmon of Doubt, and fall into three categories. From oldest to most recent, they are: “The Old Salmon,” “The Salmon of Doubt,” and “LA/Rhino/Ranting Manor.” Reading through these various versions, I decided that for the purposes of this book, Douglas would be best served if I stitched together the strongest material, regardless of when it was written, much as I might have proposed doing were he still alive. So from “The Old Salmon” I reinstated what is now the first chapter, on DaveLand. The following six chapters come intact from the second, and longest, continuous version, “The Salmon of Doubt.” Then, with an eye to keeping the story line clear, I dropped in two of his three most recent chapters from “LA/Rhino/Ranting Manor” (which became Chapters Eight and Nine). For Chapter Ten I went back to the last chapter from “The Salmon of Doubt,” then concluded with the final chapter from Douglas’s most recent work from “LA/Rhino/Ranting Manor.” To give the reader a sense of what Douglas planned for the rest of the novel, I preceded all this with a fax from Douglas to his London editor, Sue Freestone, who worked closely with Douglas on his books from the very first.

Inspired by reading these Adams treasures on the CD-ROM, I enlisted the invaluable aid of Douglas’s personal assistant, Sophie Astin, to cast the net wider. Were there other jewels we might include in a book tribute to Douglas’s life? As it turned out, during fallow periods between books or multimedia mega-projects, Douglas had written articles for newspapers and magazines. These, together with the text on the CD-ROM, provided the magnificent pool of writings that gave life to this book.

The next task was selection, which involved not the slightest shred of objectivity. Sophie Astin, Ed Victor, and Douglas’s wife, Jane Belson, suggested their favorite bits, beyond which I simply chose pieces I liked best. When Douglas’s friend and business partner Robbie Stamp suggested the book follow the structure of Douglas’s website (“life, the universe, and everything”), everything fell into place. To my delight, the arc of the collected work took on the distinct trajectory of Douglas Adams’s too brief but remarkably rich creative life.

My most recent visit with Douglas took place in California, our afternoon stroll along Santa Barbara’s wintry beach punctuated by running races with his then six-year-old daughter, Polly. I had never seen Douglas so happy, and I had no inkling that this time together would be our last. Since Douglas died he has come to mind with astonishing frequency, which seems to be the experience of many who were close to him. His presence is still remarkably powerful nearly a year after his death, and I can’t help thinking he had a hand in the amazing ease with which this book came together. I know he would have keenly wanted you to enjoy it, and I hope you will.

— Peter Guzzardi

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

FEBRUARY 12, 2002

The Salmon of Doubt

Prologue

Nicholas Wroe, in The Guardian

SATURDAY, JUNE 3, 2000

In 1979, soon after The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was published, Douglas Adams was invited to sign copies at a small science-fiction bookshop in Soho. As he drove there, some sort of demonstration slowed his progress. “There was a traffic jam and crowds of people were everywhere,” he recalls. It wasn’t until he had pushed his way inside that Adams realised the crowds were there for him. Next day his publisher called to say he was number one in the London Sunday Times best-seller list and his life changed forever. “It was like being helicoptered to the top of Mount Everest,” he says, “or having an orgasm without the foreplay.”

Hitchhiker had already been a cult radio show, and was made in both television and stage versions. It expanded into four more bo

oks that sold over 14 million copies worldwide. There were records and computer games and now, after twenty years of Hollywood prevarication, it is as close as it’s ever been to becoming a movie.

The story itself begins on earth with mild-mannered suburbanite Arthur Dent trying to stop the local council demolishing his house to build a bypass. It moves into space when his friend, Ford Prefect—some have seen him as Virgil to Dent’s Dante—reveals himself as a representative of a planet near Betelgeuse and informs Arthur that the Earth itself is about to be demolished to make way for a hyperspace express route. They hitch a ride on a Vogon spaceship and begin to use the Hitchhiker’s Guide itself—a usually reliable repository of all knowledge about life, the universe and everything.

Adams’s creativity and idiosyncratic intergalactic humour have had a pervasive cultural influence. The phrase “hitchhiker’s guide to ...” quickly became common parlance, and there have been numerous copycat spoof sci-fi books and TV series. His Babel fish—a small fish you can place in your ear to translate any speech into your own language—has been adopted as the name of a translation device on an Internet search engine. He followed up his success with several other novels as well as a television programme, and a book and CD-ROM on endangered species. He has founded a dot-com company, H2G2, that has recently taken the idea of the guide full circle by launching a service that promises real information on life, the universe, and everything via your mobile phone.

Much of his wealth seems to have been spent fuelling his passion for technology, but he has never really been the nerdy science-fiction type. He is relaxed, gregarious, and a solidly built two meters tall. In fact, he has more the air of those English public-school boys who became rock stars in the 1970s; he once did play guitar on stage at Earls Court with his mates Pink Floyd. In a nicely flash touch, instead of producing a passport-size photo of his daughter out of his wallet, he opens up his impressively powerful laptop, where, after a bit of fiddling about, Polly Adams, aged five, appears in a pop video spoof featuring a cameo appearance by another mate, John Cleese.

So this is what his life turned into; money, A-list friends, and nice toys. Looking at the bare facts of his CV—boarding school, Cambridge Footlights, and the BBC—it seems at first sight no surprise. But his has not been an entirely straightforward journey along well-worn establishment tracks.

Douglas Noel Adams was born in Cambridge in 1952. One of his many stock gags is that he was DNA in Cambridge nine months before Crick and Watson made their discovery. His mother, Janet, was a nurse at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, and his father, Christopher, had been a teacher who went on to become a postgraduate theology student, a probation officer, and finally a management consultant, which was “a very, very peculiar move,” claims Adams. “Anyone who knew my father will tell you that management was not something he knew very much about.”

The family were “fairly hard up” and left Cambridge six months after Douglas was born to live in various homes on the fringes of East London. When Adams was five, his parents divorced. “It’s amazing the degree to which children treat their own lives as normal,” he says. “But of course it was difficult. My parents divorced when it wasn’t remotely as common as it is now, and to be honest I have scant memory of anything before I was five. I don’t think it was a great time, one way or another.”

After the breakup, Douglas and his younger sister went with their mother to Brentwood in Essex, where she ran a hostel for sick animals. He saw his by now comparatively wealthy father at weekends, and these visits became a source of confusion and tension. To add to the complications, several step-siblings emerged as his parents remarried. Adams has said that while he accepted all this as normal on one level, he did “behave oddly as a result,” and remembers himself as a twitchy and somewhat strange child. For a time his teachers thought he was educationally subnormal, but by the time he went to the direct-grant Brentwood Prep School, he was regarded as extremely bright.

The school boasts a remarkably diverse list of postwar alumni: clothing designer Hardy Amies; the disgraced historian David Irving; TV presenter Noel Edmonds; Home Secretary Jack Straw; and London Times editor Peter Stothard were all there before Adams, while comedians Griff Rhys Jones and Keith Allen were a few years behind him. There are four alumni—two Labour and two Conservative—in the current House of Commons. In a scene that now seems rather incongruous in the light of Keith Allen’s hard-living image, it was Adams who helped the seven-year-old Allen with his piano lessons.

When Adams was thirteen, his mother remarried and moved to Dorset, and Adams changed from being a “day boy” at the school to a boarder. It appears to have been an entirely beneficial experience. “Whenever I left school at four in the afternoon, I always used to look at what the boarders were doing rather wistfully,” he says. “They seemed to be having a good time, and in fact I thoroughly enjoyed boarding. There is a piece of me that likes to fondly imagine my maverick and rebellious nature. But more accurately I like to have a nice and cosy institution that I can rub up against a little bit. There is nothing better than a few constraints you can comfortably kick against.”

Adams ascribes the quality of his education to being taught by some “very good, committed, obsessed and charismatic people.” At a recent party in London he confronted Jack Straw on New Labour’s apparent antipathy to direct-grant schools, on the basis that it had done neither of them much harm.

Frank Halford was a master at the school and remembers Adams as “very tall even then, and popular. He wrote an end-of-term play when Doctor Who had just started on television. He called it ‘Doctor Which.’” Many years later, Adams did write scripts for Doctor Who. He describes Halford as an inspirational teacher who is still a support. “He once gave me ten out of ten for a story, which was the only time he did throughout his long school career. And even now, when I have a dark night of the soul as a writer and think that I can’t do this anymore, the thing that I reach for is not the fact that I have had best-sellers or huge advances. It is the fact that Frank Halford once gave me ten out of ten, and at some fundamental level I must be able to do it.”

It seems that from the beginning Adams had a facility for turning his writing into cash. He sold some short, “almost haiku-length,” stories to the Eagle comic and received ten shillings. “You could practically buy a yacht for ten shillings then,” he laughs. But his real interest was music. He learned to play the guitar by copying note for note the intricate finger-picking patterns on an early Paul Simon album. He now has a huge collection of left-handed electric guitars, but admits that he’s “really a folkie at heart. Even with Pink Floyd on stage, I played a very simple guitar figure from ‘Brain Damage’ which was in a finger-picking style.”

Adams grew up in the sixties, and the Beatles “planted a seed in my head that made it explode. Every nine months there’d be a new album which would be an earth-shattering development from where they were before. We were so obsessed by them that when ‘Penny Lane’ came out and we hadn’t heard it on the radio, we beat up this boy who had heard it until he hummed the tune to us. People now ask if Oasis are as good as the Beatles. I don’t think they are as good as the Rutles.”

The other key influence was Monty Python. Having listened to mainstream British radio comedy of the fifties he describes it as an “epiphanous” moment when he discovered that being funny could be a way in which intelligent people expressed themselves—“and be very, very silly at the same time.”

The logical next step was to go to Cambridge University, “because I wanted to join Footlights,” he says. “I wanted to be a writer-performer like the Pythons. In fact I wanted to be John Cleese and it took me some time to realise that the job was in fact taken.”

At university he quickly abandoned performing—“I just wasn’t reliable”—and began to write self-confessed Pythonesque sketches. He recalls one about a railway worker who was reprimanded for leaving all the switches open on the southern region to prove a point about existentialism;

and another about the difficulties in staging the Crawley Paranoid Society annual general meeting.

The arts administrator Mary Allen, formerly of the Arts Council and the Royal Opera, was a contemporary at Cambridge and has remained a friend ever since. She performed his material and remembers him as “always noticed even amongst a very talented group of people. Douglas’s material was very quirky and individualistic. You had to suit it, and it had to suit you. Even in short sketches he created a weird world.”

Adams says, “I did have something of a guilt thing about reading English. I thought I should have done something useful and challenging. But while I was whingeing, I also relished the chance not to do very much.” Even his essays were full of jokes. “If I had known then what I know now, I would have done biology or zoology. At the time I had no idea that was an interesting subject, but now I think it is the most interesting subject in the world.”

Other contemporaries included the lawyer and TV presenter Clive Anderson. The culture secretary Chris Smith was president of the union. Adams used to do warm-up routines for debates, but not because of any political interest: “I was just looking for anywhere I could do gags. It is very strange seeing these people dotted around the public landscape now. My contemporaries are starting to win lifetime achievement awards, which obviously makes one feel nervous.”

After university, Adams got the chance to work with one of his heroes. Python member Graham Chapman had been impressed by some Footlights sketches and had made contact. When Adams went to see him, he was asked, much to his delight, to help out with a script Chapman had to finish that afternoon. “We ended up working together for about a year. Mostly on a prospective TV series which never made it beyond the pilot.” Chapman at this time was “sucking down a couple of bottles of gin every day, which obviously gets in the way a bit.” But Adams believes he was enormously talented. “He was naturally part of a team and needed other people’s discipline to enable his brilliance to work. His strength was flinging something into the mix that would turn it all upside down.”