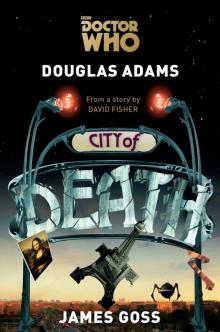

City of Death

Douglas Adams

CITY OF DEATH

THE CHANGING FACE OF DOCTOR WHO

This book portrays the fourth incarnation of Doctor Who, whose physical appearance later changed when he lost an argument with gravity.

THE CHANGING FACE OF SCAROTH

This book portrays the twelfth and final incarnation of Scaroth, last of the Jagaroth.

Doctor Who Books from Ace

SHADA: THE LOST ADVENTURE BY DOUGLAS ADAMS

by Gareth Roberts

THE WHEEL OF ICE

by Stephen Baxter

CITY OF DEATH

by Douglas Adams & James Goss

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

Published by arrangement with BBC Books, an imprint of Ebury Publishing. Ebury Publishing is one of the Penguin Random House group companies.

Original script © Completely Unexpected Productions Ltd and David Fisher 2015

This novelization © James Goss 2015

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

ACE and the “A” design are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

For more information, visit penguin.com.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-698-41228-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Adams, Douglas, 1952–2001.

City of death / Douglas Adams, James Goss. — Ace hardcover edition.

pages ; cm. — (BBC Doctor Who series)

At head of title: Doctor Who

“From an original story by David Fisher.”

ISBN 978-0-425-28390-5 (hardcover)

1. Doctor (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Extraterrestrial beings—Fiction. 3. Time travel—Fiction. I. Goss, James, 1974– author. II. Doctor Who (Television program : 1963–1989). III. Title. IV. Title: Doctor Who.

PR6051.D3352C58 2015

823'.914—dc23

2015019304

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Ace hardcover edition / October 2015

Editorial Director: Albert DePetrillo

Series Consultant: Justin Richards

Project Editor: Steve Tribe

Cover design: Two Associates © Woodlands Books Ltd

BBC, DOCTOR WHO and TARDIS (word marks, logos and devices) are trademarks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. K-9 was originally created by Bob Baker and Dave Martin.

Doctor Who is a BBC Wales production for BBC One.

Executive producers: Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors’ imaginations or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

Doctor Who Books from Ace

Title Page

Copyright

PART ONE 1: ALL ROADS LEAD TO PARIS

2: ISN’T IT NICE?

3: A PAINTING LIKE . . .

4: LOOK TO THE LADY

5: MIXED DOUBLES

PART TWO 6: PARIS IN A DAY

7: LIES BENEATH

8: UNIQUE PLURALS

9: COUNT DOWN

PART THREE 10: RENAISSANCE MAN

11: FOLLIES

12: DÉJÀ VU

13: THE FATHER OF INVENTION

14: MATERIAL WITNESS

PART FOUR 15: THE DISCREET CHARM OF THE BOURGEOISIE

16: GOODBYE, NOT AU REVOIR

17: WE’LL NEVER HAVE PARIS

18: À LA RECHERCHE DU TEMPS PERDU

19: FRENCH WITHOUT TEARS IN THE FABRIC OF SPACE-TIME

Afternote

PART ONE

One’s emotions are intensified in Paris—one can be more happy and also more unhappy here than in any other place . . . There is nobody so miserable as a Parisian in exile.

Nancy Mitford, The Pursuit of Love

1

ALL ROADS LEAD TO PARIS

It was Tuesday and life didn’t happen. Wednesday would be quite a different matter.

Scaroth, last of the Jagaroth, was in for a surprise. For one thing, he had no idea he was about to become the last of the Jagaroth.

If you’d asked him about the Jagaroth a mere, say, twenty soneds ago, he’d have shrugged and told you they were a savage and warlike race and that, if you weren’t happy about that, you should meet the other guys.

By and large, all life in the universe was pretty savage and warlike. Show me a race of philosophers and poets, said Scaroth, and I’ll show you lunch. It would, however, be unfair to say the Jagaroth were completely without accomplishments. They did build very nice-looking spaceships, although they were not necessarily very good ones. There was a lot to recommend the Sephiroth. A vast sphere rested on three claws. It suggested formidable menace whilst evoking the kind of insect you’d not care to find in your bed. The tripod arrangement of the legs also meant that it could land on anything.

Which was ironic, as right now it couldn’t take off from anything. Something had gone very badly wrong in the drive unit almost as soon as they’d landed in this desolation. They’d been hunting a Racnoss energy signal and had made planetfall, hoping for one more victory. Just one more victory.

The Jagaroth had devoted themselves to killing. There was nothing else they’d leave behind them. No history, no literature, and no statues. As a species they’d never achieved anything other than wiping out life.

The problem was that every other life form was equally dedicated to the same goal. So successful had everyone been that there really wasn’t that much life left in the universe. The Jagaroth were one of the last ones standing and, even then, not by much. When the Jagaroth talked about their fearsome battle fleet, the Sephiroth was pretty much it. Or, actually, just it.

Scaroth, pilot of the Sephiroth, battle fleet of the Jagaroth, worried about this. Nice-looking spaceships, frankly mediocre drive systems, rhyming names, and, oh yes, a frankly lunatic determination to keep going.

Hence the voices of his shipmates that filled his command pod from across the ship.

‘Twenty soneds to warp thrust.’ Someone was counting down.

‘Thrust against planet surface set to power three.’ And someone down in engineering was really keen on getting off this rock.

‘Negative,’ Scaroth snapped back quickly. ‘Power three too severe.’ Warp thrust was used to speed between the stars, not for lift-off. Even from a thinly atmosphered, low-gravity dead world. There were too many things which could go wrong. Warp thrust from a planet’s surface had not been tested. ‘At power three this is suicide.’

The voices urging him on fell silent at that. Of course they would.

‘Please advise,’ he said curtly.

Eventually that keen voice in engineering came on the line. ‘Scaroth, it must be power three. It must be.’

Typical. The refuge of the Jagaroth in definite absolutes. Scaroth twisted his face into a cynical expression. Well, as cynical an expression as could be conveyed by a face that was a mass of writhing green tentacles grouped

around a single eye.

As pilot, Scaroth was in charge. The one to push the button. If history remembered this at all, it would be his fault. He knew that it was a stupid decision, but then again, from an evolutionary point of view, the Jagaroth had made a lot of fairly stupid decisions.

‘Ten soneds to warp thrust,’ prompted the countdown. Was there a trace of desperation in the voice?

Scaroth ran his green hands over the terminal. If the Sephiroth had been working properly, warp control would have been a mass of status read-outs, all of which he had been carefully trained to simultaneously process. Instead, most of the panels flashed up requesting urgent software updates, or were simply blank.

Scaroth was relying on his instincts and the voices filling the module. And the rest of the crew seemed happy to leave it up to him.

‘Advise!’ he repeated, hoping to hear someone speaking sense.

The response that came was weary. ‘Scaroth, the Jagaroth are in your hands. Without secondary engines we must use our main warp thrust. You know this. It is our only hope. You are our only hope.’

Thanks for that, thought Scaroth, his tentacles now positively quivering with cynicism. ‘And I’m the only one directly in the warp field!’ In other words, I’ll be the first one to go. ‘I know the dangers.’ That was as close as a Jagaroth had ever come to asking for a rethink. Once they committed to an idea, no matter how lethal or ludicrous, the Jagaroth stuck to it.

Confirming his thoughts, the countdown came back on, sounding quite determinedly chipper. Whatever, something was going to happen now. ‘Three soneds . . . two . . . one . . .’ went the voice, as though unaware that the soned’s days as a unit of measurement were about to be very firmly over.

Scaroth had a last attempt. ‘What will happen if . . . ?’ It all goes wrong? If the atmosphere and gravity combine with the warp thrust to do something really unexpected and horrible? Starting with me.

Ah well. What’s the use? Arguing with the Jagaroth had only ever ended in death.

Scaroth pressed the button.

* * *

At full power, the Sephiroth glided majestically up from the surface of the desolation. The idea of staying a moment longer here had appalled the crew. Why stay here on a dead world fiddling with repairs when we could go somewhere else and maybe wipe out another species? The omens were good. A tiny fluctuation caused by a fuel leakage seemed to right itself. As the sphere rose, the claw-like legs tucked themselves neatly up underneath. For a moment the sphere hovered there, glowing with energy, magnificent, expectant.

Then it shattered.

* * *

Directly inside the warp field, Scaroth was both intimately aware of the ship falling into itself and also strangely removed from the experience. Nothing seemed certain except that everything hurt. And the voices of the Jagaroth were still filling warp control.

There was no sense that they realised they had made a terrible mistake, that they’d made him press the button. Simply that they now expected him to do something about it.

‘Help us Scaroth! Help us!’ they pleaded. As if there was anything he could do now. ‘The fate of the Jagaroth is with you! Help us! You are our only hope!’

The screaming voices cut off and, for a brief moment, Scaroth could enjoy his agony in relative silence.

I’m the last of the Jagaroth, he thought. For as long as that lasts.

* * *

The warp field finally, mercifully collapsed. The fragments of the ship, squeezed into place by impossible forces, finally felt free to fling themselves in burning splendour far and wide across the surface of the dead planet.

Scaroth died. And then the surprising thing happened.

* * *

That’ll do, thought Leonardo.

Like most works of genius, it had arrived almost without being noticed.

One moment there it wasn’t, the next there it was, somehow squeezing itself between the towers of paper and the dangling models that filled the cramped study.

Leonardo sat back in his chair and surveyed the painting, brush still in his hand. The brush hovered near the lip of the easel, not quite being laid to rest. He surveyed his work. Was that really it? Was there anything more that needed doing to it?

Finally, he tugged his eyes away from the painting. He looked over to the visitor snoring in the corner, boots up on the model of the dam designed for Machiavelli. Leonardo briefly toyed with the visitor’s suggestions, no doubt kindly meant, about the portrait’s face.

But no, he thought. He would come back to the painting, of course he would come back to it. That was his problem. Never quite able to finish anything. But yes, she would certainly do for now.

He let his brush fall, excitement turning into a vague sense of anti-climax and now what.

Deciding that tonight would be a drinking night, he poured himself a cup of cheap wine, and sipped it fearfully. Perhaps he’d buy something better tomorrow, but he probably wouldn’t. He gazed out through the arched window at the stars and the city slumbering beneath them. His eyes wandered across the squares of Florence. God alone knows what they’ll make of this on the forums, he thought. He knew that tomorrow all the whispering would be about his latest painting. Some would say it was a disappointment. Others would say he should stop dividing his time between painting and inventing. No doubt a few would say it was a triumphant return to form.

Ah well, let them. He was happy with it. More or less.

His visitor shifted in his slumber, and Leonardo wondered about the portrait’s face again.

No. Leave her be. For the moment.

He rocked back in his chair, enjoying the wine as much as was humanly possible, and drinking in the painting. She had been a struggle, and, while he wasn’t quite at the top of the mountain, the struggle had definitely been worth it.

Thank the Lord he wouldn’t have to go through that again.

* * *

William Shakespeare was cheating at croquet. His visitor frowned and, while the Bard wasn’t looking, subtly scuffed his ball closer to a hoop. He looked up. Well, bless him if William hadn’t done the same thing. The two smiled at each other politely.

‘Patrons!’ exclaimed Shakespeare, changing the subject.

His visitor nodded and clucked sympathetically.

‘This one’s very keen,’ continued the Bard. ‘I tried out some of my new stuff on him last night. Normally that sends them scurrying away for weeks, but this one’s promised he’s coming back at the weekend. So he must have more.’ He angled his mallet and sent the ball bouncing merrily across his lawn, neatly avoiding his visitor’s scarf, which was unaccountably trailing across its path. The ball sailed through a hoop and smacked against the post. Shakespeare smirked.

‘Oh, well done,’ applauded his guest insincerely.

‘He was very nice about a bit I was pleased with.’ Shakespeare waited, both for a dramatic pause and for his visitor to miss his shot. ‘Ah yes,’ he announced with a studied spontaneity which explained why he’d given up acting. ‘I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I had bad dreams. Yes, that was it. He said it spoke to him and he couldn’t wait to find out how it ends. Pah! Wonder what his bad dreams are, eh? Probably nothing much. Oh poor you, that is a shame.’ As his visitor muffed his shot completely.

All thoughts of his patron’s bad dreams banished, Shakespeare got on with winning the game.

* * *

It was said that the Nazis loved art as much as they loved a joke. Curiously, however, as they’d stormed into Paris they’d filled their lavish hotel suites with as much art as they could lay their hands on. And, when they’d swept out of Paris the first thing they’d done was to take their art with them. And the last thing they’d done was to forget to settle their hotel bills.

The train had been loaded by the Wehrmacht in the dead o

f night. It was one of the final ones to leave Paris, rattling slowly through the north-eastern suburbs, windowless metal containers baking in the summer heat. Behind the train came the steady, self-important crump of the American army. Ahead of the train lay Germany.

Inside one of the carriages was a very young German soldier, his poise stiff, even if his uniform was several sizes too large. His posture didn’t waver, not even when the train juddered to an abrupt and unexpected halt just outside Aulnay. The tracks ahead were gone, blown up by the Resistance.

The young soldier could hear gunfire, shouts and footsteps walking down the track towards his carriage. He pulled out his gun and waited. The young soldier made a list of his options. He could fight his way out (unlikely), he could shoot himself (practical), he could set fire to the cargo (regrettable). For once, he took no action, and simply stood to attention as the bolts were undone and the container door slid to one side.

A flashlight landed on his handsome, perfectly Aryan face. The soldier tensed, just a little, expecting the shot that would end his life.

It did not come.

‘Good evening.’ The voice behind the flashlight sounded endlessly amused. ‘Well, it all seems to be in order.’ The light played over the contents of the carriage, some neatly in crates, the rest stacked up against walls. The carriage was full of paintings. ‘Tell me, what do you think of it?’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘I said,’ the voice purred, ‘what do you make of it all?’

The soldier found his voice. ‘It is all excellent.’

‘Yes, it is, isn’t it?’ the man’s voice laughed. ‘And it’s mine.’ The tone shifted just a little, addressing him like a hotel porter. ‘Thank you for looking after it so well . . .’ A pause. A question.

‘Hermann, sir.’

He could hear the man nod. ‘Thank you for looking after it, Hermann.’

* * *

Major Gaston Palewski glared at the mountain. It did not explode.