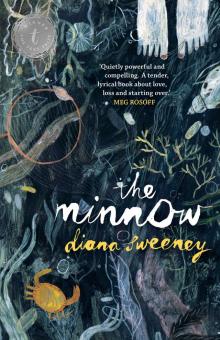

The Minnow

Diana Sweeney

Diana Sweeney was born in Auckland and moved to Sydney at the age of twelve. She now lives in northern New South Wales.

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Diana Sweeney 2014

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in Australia by The Text Publishing Company 2014

Cover and page design by Imogen Stubbs

Cover illustration by Katie Harnett

Typeset by J&M Typesetters

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Sweeney, Diana.

Title: The minnow / by Diana Sweeney.

ISBN: 9781922182012 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925095012 (ebook)

Subjects: Bildungsromans.

Grief—Juvenile fiction.

Dewey Number: A823.4

for Mum

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Acknowledgments

‘I think Bill is in love with Mrs Peck,’ I confide to an undersized blue swimmer crab that has become all tangled up in my line. The little crab doesn’t appear to be the slightest bit interested, so I finish pulling it free and toss it over the side of Bill’s dinghy. It makes a plopping sound as it enters the water and I watch it swim away. Bill, as usual, is asleep. He sleeps with his hand dangling over the edge, the line tied to his little finger. Sometimes I have to kick him awake, although he swears he always feels the fish tugging. That’s Bill. Bit of a liar.

I live with Bill in the boatshed at Jessops Creek. I moved in after the Mother’s Day flood. I’m used to it now, but I missed my old room at first. Nana says you get used to anything if you’ve got enough time. She says she still misses Papa—my grandfather—even though he died before I was born. I keep a photo of Papa next to my bed. Nana gave it to me after the flood. She said Papa would keep me company. She said he had been doing such a fine job of keeping her company over the years, she was sure he had special powers. Nana lives at the Mavis Ornstein Home for the Elderly. She has given photos of Papa to everyone there.

I sleep in the loft. It’s small, but perfect for me. It used to be Bill’s bedroom, but the ceiling is really low so I don’t think he minded moving downstairs. When I asked him about it, he just shrugged and said headroom was highly overrated.

I totally disagree. My old bedroom had lots of headroom. I could stand on the bedside table with my arms outstretched and still not reach the ceiling. Now, if I stand up really straight, the top of my head already touches the beam. If I keep growing I’ll have to bend my neck. I often think about that headroom. I miss it.

Instead of windows, the loft has large double doors that open onto the roof. They’re closed during the day to keep out the heat, but at night, with them propped wide open, I can watch the sky. One of the old ladies at Nana’s home gave me her astronomy chart when I told her about my stargazing. She said ‘such enthusiasm should be nurtured’. Her name is Mavis; she is ninety-eight, and she thinks the home is named after her. She also thinks Papa is her late husband. Nana said she almost regretted giving a photo to Mavis until she realised it was just another example of Papa’s special powers. Mavis was happy, Nana said. Why spoil it with the truth?

There is a flash of silver near my line, so I keep my hand steady and my body still, willing the fish towards the bait. Bill yawns loudly. I ignore him. Bill hates to be watched as he wakes.

‘Not much is happening,’ he says.

Bill has a beard, and his arms and legs are thick with hair. He always jokes that no one ever got sunburnt wearing a fur coat and, generally speaking, he’s right. But today he has forgotten his cap and his nose and forehead are quite red.

‘Your face has copped it,’ I say, without a trace of smugness.

I always wear a long-sleeved shirt and a hat when I’m outside. It was one of Mum’s rules.

The last time I saw Sarah she was floating head down with her arms and legs out from her sides like a star fish. I watched her from the roof of the fire station, counting the seconds. She held the record at fifty-two. I counted to sixty as she disappeared around the side of the newsagent. I remember thinking she was probably sneaking a breath.

Bill and I usually fish from the pier, where the fish come in only two sizes: dinner-for-four or not-worth-it. We always let the little ones go. Bill says it’s one of the laws of fishing. But I feel sorry for the ones that get thrown back, swimming around with a hole through their lip (or worse).

‘I think it’s kinder to keep them and eat them,’ I said to Bill, once.

‘Don’t put a hook on your line if it bothers you so much,’ Bill snarled back. Sometimes Bill can be mean.

When it’s too windy at the pier, we fish down at Crabs Gully. It takes ages to get there. Bill says Crabs Gully is one of the Seven Wonders of the World because it’s a wonder we ever make it out alive. Ha ha.

There are heaps of blowholes at Crabs Gully, so we usually get soaked-to-misery. Soaked-to-misery is one of Nana’s favourite sayings. She has a particular hankering for cold and wet situations and loves to say stuff like, ‘the shivers are no match for Bovril’ or ‘you can’t stay miserable on a full belly’. Bill doesn’t understand Nana’s sayings.

Anyway, by the time we make it back to the boatshed I’m usually so cold my teeth are chattering. Bill always lights the pot-belly, then we eat soup till we burst. Bill only ever eats soup. He says he can’t see the point of anything else. Nana reckons his teeth are probably crook.

Some days Bill and I catch the bus into town. Bill always needs new line and I like to look around at stuff. The best shop in town is Mingin’s Hardware and Disposals.

‘Hi, Bill,’ says Mrs Peck.

‘Why, I believe you’ve had your hair done, Mrs Peck,’ says Bill in a voice he never uses with me. Mrs Peck flicks her head. ‘And is that a new dress?’ Bill continues, all smooth and soothing, like maybe he wants to see her naked.

‘I’m going to look at the sinkers,’ I say to no one in particular, because no one in particular is listening. I love sinkers. I love to feel their weight in my hand. It amazes me that something so small can be so heavy. Bill says gold is even heavier. I can’t imagine.

Bill’s hand is moving under Mrs Peck’s dress. I slip a number-four sinker into my pocket and move over to the tackle boxes. You’d have to be mighty serious about fishing to want a tackle box. I stop in front of the FishMaster Super Series. It comprises three layers that concertina for ease of access. It says that on the lid. I don’t usually use the word ‘comprises’, but I think it sounds just right. I open it. It’s got a separate lock-up storage compartment for sharps and a see-through sinker box. If you buy the deluxe model you get the sinker box for free. I’ve never owned a tackle box. Bill and I only ever take a roll of line, a dozen hooks, a few sinkers and a knife. Bill reckons anything more is window dressing. Sometimes w

e buy worms, but usually we collect cabbage off the rocks. The fish love it. I’ve gotten most of my sinkers from Mingin’s Hardware and Disposals.

Bill is pushing himself against Mrs Peck’s hip. I should tell you I don’t like Mrs Peck. She has an ugly grouper’s mouth which she paints bright red and she makes a dry clicking sound when she speaks. She has a horrible habit of wetting her lips with her tongue, something she does at the end of every sentence. I try not to look.

Right now, she’s pushing her tongue into Bill’s ear, pretending for all she’s worth to be absorbed in his attentions. In actual fact, she is monitoring my every move. The only time she takes her eyes off me is to glance at the door—probably checking for Mr Peck—meanwhile, Bill has his back to the world and nothing to lose.

They’ve decided to move away from the counter. Bill leads Mrs Peck over to the paint aisle. It’s near the back of the shop, which gives them time to finish up if a customer comes in. Mrs Peck’s son arrived once. Bill pretended to check the colour chart while Mrs Peck was on her knees. ‘G’day Junior,’ Bill called out to the kid, all casual, but keeping his hand hard on Mrs Peck’s head until he was done. Sometimes Mrs Peck climbs the paint ladder and Bill stands under her dress. I have a Swiss Army knife that I got the day Bill had Mrs Peck on her back in the Deluxe Family Weekender. Mr Peck was on a buying trip and Mrs Peck had thrown caution to the wind. ‘Here you are, Tom,’ she’d said, pushing a small red box into my hand. ‘Be sure to check all its features.’ Click, click.

The Swiss Army knife has everything: three knives, a pair of scissors, a toothpick, a bottle opener, a fish scaler, a nail cleaner and a small file that fits easily into the keyhole on the side of Mingin’s register. I would have liked some coins to buy a Coke, but the change would have rattled against the sinker in my pocket, so I grabbed a lobster—that’s slang for a twenty.

I’m poring over the catalogue when Bill and Mrs Peck reappear.

‘Next time, I’m going to tie you up,’ Bill whispers to Mrs Peck as she hands him a brand new roll of line. I make a throat-clearing sound.

‘I’d like that,’ Mrs Peck purrs, ignoring me. I imagine her lip all torn and bloody as I pull a rusty hook from her mouth.

‘Thanks for the supplies,’ Bill calls over his shoulder as we leave the shop. ‘Hungry?’ he asks me.

Martha’s Grill is Bill’s favourite spot for lunch, which is lucky because I like it too. I order the fisherman’s breakfast and Bill orders the soup of the day. Martha is young and handsome and not really Martha. The real Martha sold up when her husband died, but everyone in town just went on calling the new owner Martha, even though he’s nothing like Martha at all. I’m too young to remember much about the old Martha, I’m just telling you what I know.

After Martha’s Grill, we head to the public pool on Cooper-Brian Street. In order to swim, you have to have a shower first. The boatshed doesn’t have a shower, so the pool’s amenities come in quite handy. I’m never happier than when I’ve had a shower, a swim and a fisherman’s breakfast, and Bill’s at his best after a good workout with Mrs Peck.

After the flood, some of the older folk formed the Mother’s Day Survivors, and they’ve met every Tuesday night ever since. Christmas day fell on a Tuesday last year and the place was packed. Bill and I went, even though we’re not official members. No one seemed to mind. I often wish I’d known how to fish before the flood. I could have pushed hooks through everyone’s mouths and tied the lines to the roof of the fire station.

Most nights it starts to rain about midnight. Just soft spits, not enough to wake me. Before the weather changed it used to be drier than Mrs Peck’s mouth. The ground was hard and dusty. Grass never grew on the oval, and Mum’s flowers always died out the front. We used to swim in the neighbour’s dam when it got really hot.

‘Are you fishing or wishing?’ Bill asks me when there’s a tug on my line.

It’s a little catfish. Far too undersized to keep. As I unhook it, I think of my sister floating away, her head under the water looking at the things in the sea. The catfish asks me what I’m doing, its little mouth mouthing the words.

‘I’m throwing you back, Sarah,’ I say. ‘You belong in the water now, and I belong here with Bill.’

‘Have you had sex yet?’ she asks. But I can’t answer because Bill is watching me talk to a fish and I feel stupid.

The answer is yes, if you must know. I had sex a few weeks ago. It happened unexpectedly, after a Martha’s breakfast, at the public pool. I was in the change room, stripping off my wet boardies when Bill walked in. ‘Tom,’ Bill said, staring at me, mouth gapping, ‘you’re a girl.’

My name hasn’t always been Tom. It used to be Tomboy and before that it was Holly. Even Nana calls me Tom. I’ve been Tom so long, even if I changed back to Holly, no one would take any notice—look at poor Martha. So, for almost a year, living in the boatshed, Bill thought I was a boy. Maybe he wouldn’t have taken me in, if he had known I was a girl.

Anyway, we mucked around a bit until I’d had sex. I’ve never felt like doing it again, and Bill and I pretend it never happened.

But it changed everything.

I want to tell someone. I want to tell Jonah. Jonah is a year and a half older than me and he is my best friend. We have known each other since we were toddlers. He lost his family in the flood, too.

We used to see each other every day, tell each other everything, but we’ve both been dealing with our own stuff and we’ve sort of lost touch. Nana always asks after him.

‘You used to live in each other’s pockets.’

‘You’d be so good for each other, the things you’ve gone through.’

‘Don’t you miss him?’

‘I can’t believe you don’t miss him.’

She has been saying stuff like this for months.

I taught Sarah to float in the neighbour’s dam. She caught on really fast, and in a really short time she was actually better at it than me. Mum said it meant I was a good teacher. But she was just being sweet. The truth was obvious; I hated the feeling of water in my ears, but it never bothered Sarah. This meant she could lie flat on her back, ramrod straight, her face almost immersed. We used to have competitions to see who could last the longest. She won every time.

It is exactly three weeks since the sex. The thought of it makes me sick.

I lay in bed last night, trying not to think about the events of the past year. But trying not to think about something just makes you think about it even more. In the end, I got up, threw a hoodie and trackies over my pyjamas, crept out of the boatshed and went for a walk.

I’m not afraid of the dark; I can thank Dad for that. Dad always said that the dark had its own brand of solitude, and that people who were afraid of the dark were often afraid of their own company.

‘Relish it, Tom, it’s the best time of the day and you have it all to yourself.’

So, I thought about Dad as I walked.

I ended up at Jonah’s house. It was still the middle of the night, so I made myself comfortable on the front porch and waited for sunrise.

I guess Bill knew I couldn’t stay at the boatshed, but when I told him, he packed all my stuff into his truck and drove me straight to Jonah’s house.

‘Bye, Tom,’ he said. Bill’s not much of a conversationalist.

‘See ya,’ I said. Then I cried. I’m not sure why.

Jonah’s house is tiny. He lived here with his parents and a mangy cat called Runaway. His parents drowned, and they never found the cat. Jonah had fallen asleep on the lilo and no matter how high the water got, he just floated. Dead to the world.

After the flood, Jonah moved in with his grandfather. Jonah and Jonathan Whiting—Jonah is named after his grandfather—spent the next six months clearing debris, repairing and repainting. Jonathan hoped that the physical work would be therapeutic, that his grandson could work through his grief. But as soon as the house was liveable, Jonah begged to be allowed back home.

At fir

st, his grandfather forbade it, saying sixteen was too young to be on his own. But Jonah was miserable. Living in town was noisy; he ached for the quiet, the acres of space. Most of all he missed his parents and the closest he could get to them was the house itself. So, the following March, ten months after the flood and with lots of conditions, his grandfather agreed. A month later, I moved in.

Jonathan hadn’t counted on that.

Jonah’s house is a half-hour walk from the Mavis Ornstein Home for the Elderly, which means I can visit Nana every day. I told her about moving in with Jonah. I didn’t tell her why.

‘Marvellous, darling,’ she said on hearing the news. ‘I never liked you living with Bill, but what could I do?’

‘It’s okay, Nana. It’s all good now,’ I said.

We chat as usual. Nana tells me she’s starting an art appreciation class on Tuesday morning in the common room.

‘Painting or drawing?’ I ask.

‘No, no, dear. Art appreciation,’ she replies.

I’m not sure I know what to say, so I say nothing.

‘A young woman from one of the city colleges is doing a study on learning strengths in an ageing population,’ says Nana, in her officious voice. ‘She popped in last week to meet us and she seemed very keen. Apparently we’ll be discussing art in all its various forms.’

Nana abhors blandness on any level.

‘I bet you’ll be her favourite student,’ I say.

Nana laughs and leans forward. ‘Guinea pig more likely,’ she says.

I stay with Nana until dusk.

Her evening meal arrives as I’m leaving. The smell makes me queasy.

Jonah’s house has a bathroom with a separate shower and a small bathtub. We’re on tank water so the bath doesn’t get much use, but Jonah says I should treat myself every now and then. It’s so good to be around him. I think he feels the same. It’s like there’s been no gap.

When I told Nana how easily we fitted back into our friendship, she said we had definitely passed the best-friend test.