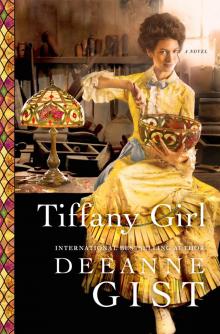

Tiffany Girl

Deeanne Gist

Thank you for downloading this Howard Books eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Howard Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

This will be the first time in my career that my dad will not have read my book.

I love you and miss you so much, Dad.

In Memory of

Harold LaVerne Graham

Both before and after I lost my dad, my beloved PIT Crew (Personal Intercessory Team) committed to stand in the gap for me every single day while I was writing this book. Their commitment, reassurance, comfort, and unfailing diligence helped me make my page counts one day at a time until the manuscript was complete.

So it is with a full heart and much emotion that I thank:

Catherine Brake

Daree Stracke

Norma Jean Ursey

When gentle suggestions for the manuscript came in from my wonderful and talented editor, my PIT Crew stepped in again and were joined by my Community Group (whom my husband and I meet with every Tuesday night for fun and fellowship).

York and Robyn Whipple

Mark and Lisa Chadwell

David and Karen Danielson

Jodie Faltynski

April Garcia

Ryan Walters

Thank you for the support, the encouragement, and the shoulders you offered during this incredibly difficult time. I will never, ever forget it.

Bless all of you a hundredfold to how you have blessed me.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I knew I wanted to write about the Tiffany Girls ever since my mom told me of their existence four years ago. When I found out there was a traveling museum exhibit featuring them, I flew my sister and assistant, Gayle Evers, to Florida to see it because I was on deadline with one of my other books.

A few months after that, she flew to the Northeast to scan thousands of pages of handwritten letters by Clara Driscoll, the manager of Tiffany’s Women’s Department in the 1890s. It took Gayle an entire week, working from morning to night. She then spent an untold number of months preparing them for me. Those letters were the cornerstone of my research, and I could not have done the book without them. It was an enormous job, and I am so very grateful to her for all she did. She has now retired and is taking a well-deserved rest and enjoying a brand-new grandbaby—her fourth. Thank you so much, Sis. You’re the best!

My critique partner—gifted author Meg Moseley—went above and beyond this time around. She has been my critique partner for ten years and is the only person on the planet who sees my work “raw.” I send it to her each week—and she sends me hers. We critique each other’s material, send it back, then do it all over again the following week. Sometimes, however, life gets in the way. This year was one of those years, and I found myself writing the lion’s share of the book very close to my deadline.

As a result, I sent Meg my chapters daily instead of weekly. She turned them around in twenty-four hours most every time. She did it again when my revisions came in. I have no words to express what her sacrifice meant to me, both professionally and emotionally. Thank you, my friend. If there’s ever anything you need, I’m your gal.

My editor, Beth Adams, offered suggestions, deletions, and additions to the manuscript that brought it up to a whole new level. She was also extremely patient and understanding during one of the most difficult seasons of my life. Thank you, Beth. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

My new agent, Lacy Lynch with Dupree/Miller, has swooped in with mounds of energy, ideas, and a go-get-’em attitude. Thanks for all you’ve done, Lacy. I stand amazed.

I can’t wait for you, my readers, to see the photos and illustrations we’ve included in this book. Since our heroine, Flossie Jayne, is an aspiring artist, I thought it would be fun to sprinkle in a few pieces of art she’d done. So I contacted the talented Monica Bruenjes—who did the wonderful stop-animation for my video adventure RompThrough1893.com. Problem is, Flossie hasn’t yet perfected her craft, so I wasn’t sure what Monica’s reaction would be, but she was very gracious and tried to make her work look “less than professional.” (I still think the results are delightful. Just can’t hide that talent under a bushel, even when she tries to.) In any event, I so appreciate her agreeing to be “Flossie” and on such a tight timetable. When I wasn’t able to secure licenses for an existing image of the Tiffany Chapel, Monica also agreed to do a rendering for us. It is simply gorgeous, and I’m so thrilled to be able to include it. Thank you, Monica!

There were many other folks along the way who offered wonderful contributions and information about our subject matter. Lindsy Parrot, the director/curator at the Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass in New York; Vincenzo Rutigliano at the Schwarzman Building of the New York Public Library; authors Kellie Coates Gilbert, Kristan Higgins, Jenna Kernan, Jenny Gardiner, Miriam Berman, and Richard Alvarez; Riccardo Gomes of the East New York Project; Lauren Sodano at the Strong National Museum of Play; Arlie Sulka of Lillian Nassau LLC; Elisha Gist; and Michael Gurrola. A huge thanks to all of you!

NOTE TO READER

I wanted to warn you that privacy as defined by a turn-of-the-century Victorian looks a great deal different than how we, today, define it. So don’t be alarmed if fellow lodgers at a boardinghouse move freely in and out of one another’s rooms without permission and with no regard as to whether the occupant of the room is even present. This was the case in private boardinghouses which catered to genteel urbanites, as well as those of more modest means.This trend is supported in many resources I studied, including first-person accounts.

I also wanted to let you know that what was politically correct in the Victorian era is hardly so today. While writing this novel, I worked extremely hard to depict what society believed at that time and have presented things from an 1893 viewpoint as best I could. (So please don’t kill the messenger!) As for the exposés our protagonist writes for his newspaper, rather than making them up, I decided to record, in many cases almost word for word, quick little snippets from articles that were written during the time. (And which are, of course, in the public domain.) I did this mostly because they were such eye-opening glimpses into our past.

Last, other than our heroine, Flossie Jayne, and her nemesis, Nan Upton, all the Tiffany Girls depicted are based on real ones, including their manager, Clara Driscoll. I have no idea what their temperaments were like or what they looked like, so I made all those parts up—including any words spoken by them, of course.

For more insider information, refer to my Author’s Note after the last page. But you might want to read the book first, because there are many spoilers in the Author’s Note.

PROLOGUE

Reeve remembered everything about that morning. He remembered the scratchy wool of his short pants. His stiff collar and bow tie making it hard to swallow. The branches of the willow tree whipping against the window. The women sitting in the parlor, the air around them saturated with their homemade herbal fragrances.

But mostly he remembered his mother. So still. Lying on a table—and in the middle of the morning when everyone knew it was the time she snapped beans from the garden. Her eyes were closed, her lips turned down, her skin a funny color.

Father shifted Reeve farther up his hip. Leaning over, Reeve reached for her. Her chin was as hard as the rocks Father skipped across the creek, and as cold, too. He jerked his hand back and looked at his father in question.

Father didn’t make a sound, but tears streamed down his cheeks.

“Poor child,” someone sobbed.

Turning away, Reeve buried his face into Father’s nec

k, the smell of his shaving soap sharp, his neck moist from sweat, or maybe tears.

Within three months Father’s dry goods store had failed. Within six, he’d taken Reeve to the doorstep of his grandparents’ house. Grandparents he’d never even known he had. Grandfather motioned him inside with a jerk of his head, then latched the door, cutting off the sight of Father.

Reeve stood in the entry hall, its walls bare, its air stale. Grandfather’s flinty eyes took in his mismatched stockings, his threadbare jacket, his stained hat. Reeve didn’t need to touch him to know he was hard as the rocks by the creek and just as cold.

SITTING ROOM 1

“Flossie used to love this room, with its northern light and view of Stuyvesant Park. Its mauve floral walls and Baghdad rug had hosted many a happy occasion.”

CHAPTER

1

New York City, 1892

Twenty-two Years Later

Your father has decided to withdraw you from the School of Applied Design.”

Flossie Jayne looked up from the muslin in her hands, her fingers pausing, her needle protruding from the cream-colored fabric. “What do you mean?”

Mother secured a porcelain button to a short basque waist of a Louis Seize brocade in rich shades of burgundy and claret. The buttons had miniatures painted onto them. Miniatures Flossie had put there with her own brush.

“I mean,” Mother said, “when your current winter session at the design school is over, you will not be going back.”

Flossie lowered the bodice lining to her lap. The whalebone sandwiched between the two pieces of muslin slipped. “But, why? The painting classes won’t be complete until next summer.”

“Your father is aware of that.” She snipped the end of the thread, then picked up another button.

“Has something happened?”

Mother said nothing. Her hair was no longer as black as Flossie’s, but had softened with silver strands and was pulled up into a twist.

“Mother, I . . . I live for those lessons. Painting is the only thing that gets me through this endless sewing.”

Even though Mother was working, she had dressed with extreme care. Her emerald gown was not as fancy as the ensembles she sewed for the upper echelons of New York society, but it was certainly nicer than that of most barber’s wives. When customers came by the house, they’d see what a fine figure she cut and would often order something similar but significantly more expensive. Thus, she and Flossie both dressed exquisitely and in the very latest fashions no matter what their plans were.

“The sewing we do is not endless,” Mother said. “Endless sewing is what those poor unfortunates in factories and sweatshops do. You and I work in our warm, cozy sitting room and handle all manner of silk, velvet, mink, lace, and jewels.”

“We sew from first light until last light, until our eyes hurt and our heads ache. We stop only to do the cooking and cleaning.” The thought of sewing without interruption was bad enough, but to give up her passion, the one thing that not only offered her a reprieve but infused her with renewed energy, was not to be borne.

“You stop every afternoon for your lessons,” Mother said.

“Which is my whole point.”

Mother tsked. “You should be happy we have the work. With so many men losing their fortunes, many seamstresses are finding themselves with fewer and fewer customers.”

“You will never lose your customers.” Flossie once again worked her needle along the edge of the whalebone, boxing it in with neat stitches. “Not when every gown you make is nothing short of a work of art.”

Mother allowed herself a small smile. “Your pieces are not far behind.”

“Even if that were true, the difference is you love to sew. I hate it. No, I loathe it. The only thing that keeps me in this chair is knowing that if I want to attend the School of Applied Design, Papa said I’d need to bring in the income myself. But if he’s not going to let me go, then what’s the point?”

The fire in the grate popped, its heat warding off December’s chill. Flossie used to love this room, with its northern light and view of Stuyvesant Park. Its mauve floral walls and Baghdad rug had hosted many a happy occasion. The sense of warmth and well-being it once induced, however, had long since dissipated, leaving dread and drudgery in its wake, for this was where she and Mother did their work week after week, day after day.

She pushed the floor with her toe, setting her rocker in motion. “He went to the races again, didn’t he?”

Mother tied off the last button. “You really did do a lovely job painting these miniatures. Mrs. Wetmore is going to be very pleased with them.”

“How much did he lose this time?” Flossie rued the day her father had been invited to the races by one of his customers. What should have been a day of leisure ended up becoming a consuming passion. He’d even started to close the barbershop on Saturdays in order to go to the racetrack.

“It’s not for you to question how your father spends his money.”

“What about how he spends our money?”

“Hush.” Mother glanced at the door as if someone might hear, but they didn’t have a maid anymore, nor a cook. “You and I don’t have any money. It’s all his.”

“Why is that? We’re the ones doing the work. We’re the ones designing the clothes. We’re the ones taking care of your clients. Why don’t we get any of the money? Why do we have to hand it all over to him?”

“Because we do.”

“What if we don’t?”

“That is quite enough.”

“I mean it, Mother. What if we simply told him no? Told him he couldn’t have it?”

Standing, Mother shook out the bodice, then held it up by its shoulders, the light glinting on its gold-braided trim. “These buttons will become more popular than they already are once the senator’s wife wears this. Perhaps tomorrow you should paint some more.”

“Let’s go on strike.”

Glancing at her sharply, Mother draped the bodice over the back of her chair. “What on earth are you talking about?”

“Let’s tell Papa we refuse to do any more work until he gives each of us a percentage of our earnings.”

Narrowing her eyes, Mother snatched up tiny scraps of fabric littering the worn oriental rug that had been in her family for generations. “You’ve been reading too many newspapers. If you’re not careful, your father will disallow it.”

“You ought to read them, too. The New York World gave a very detailed account of the feather curlers when they went on strike. It brought the entire feather industry to a standstill. By the end of it, night work was abolished and the women had won. Well, they’d won the first skirmish, anyway.” She scooted forward in her chair. “Don’t you see? If we both told Papa we wouldn’t work another day until he agreed to give us each a percentage of our work, he’d have no recourse but to give in to our demands.”

“No.”

“Then let’s just keep a portion and not tell him. They pay you, so he’d never know.”

Mother studied Flossie, her brown eyes catching the fire’s light. “Look around you, daughter. The rocker you are lounging in, the cup of tea at your elbow, the very walls that protect you from the cold . . . these are all a product of your father’s hard work. Surely you remember we haven’t always lived so well. It has taken him years to provide such nice things for us. If he wants to give himself a little treat, then I will not begrudge him and neither will you.”

“I remember we lived much more modestly until you started to take in sewing. Until you discovered you had a talent—no, a gift—for creating gowns of the highest caliber. I remember Papa being so delighted that he hired a maid and then a cook so you could devote more of your time to your sewing.” She folded the muslin lining. “Everything was wonderful at first, but it was never the same after we moved here and away from all our friends. Papa opened his new shop with fancy chairs and even fancier equipment. He joined those clubs. He stayed out late. He went to the races. He fire

d the help.”

Mother stood stiff, her lips drawn.

“I’ve heard you crying, Mother.” She looked down, picking a loose thread from the muslin. “I’m not a young girl anymore. I’m one-and-twenty. Old enough to see that something is very, very wrong.”

“We’re just going through a bad spell right now. Everyone is.” Her voice wavered.

Setting her sewing aside, Flossie stood. “But we shouldn’t be. Your business is booming and so was his, but he hardly ever opens his doors anymore. He simply takes the money we make and spends it.”

“He enrolled you in the School of Applied Design.”

“Only because you made him. And the reason I didn’t feel guilty about it was because I earned every penny of the tuition.” She bit her lip. “But as sure as the sun rises, I know that as long as we keep handing everything over to him, he’ll never change his ways. Why would he?”

“Your father’s a wonderful man.”

“He is. And I love him—very, very much. But what he’s doing to you—to us—is wrong and I’ll—I’ll not be party to it. If you want to work yourself to death and give it all to him, you are certainly free to do so, but not me. If I do the work, then I’m going to keep a portion of the wages.”

Mother closed the distance between them and lowered her voice. “You will not.”

“It’s time, Mother,” she said, matching her quiet tone. “Well past time.”

Mother slapped her.

Gasping, Flossie fell back, covering her stinging cheek. Tears sprung to her eyes. Never in her entire life had either of her parents raised a hand to her.

“We are women.” Mother’s hands trembled. “You can read all you want about unfeminine women who want to be treated like men, but no matter how hard we try, nothing will change the facts. We aren’t men. Not now, not ever. And if those women aren’t careful, they just might get what they are asking for, and then where will we be? Do you wish to load your own steamer trunks onto a wagon? To shovel snow from the sidewalk? To drive six horses? To fight in wars? To wear trousers? Well, I don’t, and I will have no such talk in this house. Have I made myself clear?”