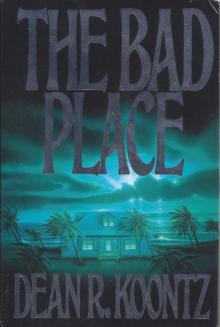

The Bad Place

Dean Koontz

Teachers often affect our lives more than they realize. From high school days to the present, I have had teachers to whom I will remain forever indebted, not merely because of what they taught me, but because they provided the invaluable examples of dedication, kindness, and generosity of spirit that have given me an unshakable faith in the basic goodness of the human species. This book is dedicated to:David O’Brien

Thomas Doyle

Richard Forsythe

John Bodnar

Carl Campbell

Steve and Jean Hernishin

Every eye sees its own special vision;

every ear hears a most different song.

In each man’s troubled heart, an incision

would reveal a unique, shameful wrong.

Stranger fiends hide here in human guise

than reside in the valleys of Hell.

But goodness, kindness and love arise

in the heart of the poor beast, as well.

—The Book of Counted Sorrows

1

THE NIGHT was becalmed and curiously silent, as if the alley were an abandoned and windless beach in the eye of a hurricane, between the tempest past and the tempest coming. A faint scent of smoke hung on the motionless air, although no smoke was visible.

Sprawled facedown on the cold pavement, Frank Pollard did not move when he regained consciousness; he waited in the hope that his confusion would dissipate. He blinked, trying to focus. Veils seemed to flutter within his eyes. He sucked deep breaths of the cool air, tasting the invisible smoke, grimacing at the acrid tang of it.

Shadows loomed like a convocation of robed figures, crowding around him. Gradually his vision cleared, but in the weak yellowish light that came from far behind him, little was revealed. A large trash dumpster, six or eight feet from him, was so dimly outlined that for a moment it seemed ineffably strange, as though it were an artifact of an alien civilization. Frank stared at it for a while before he realized what it was.

He did not know where he was or how he had gotten there. He could not have been unconscious longer than a few seconds, for his heart was pounding as if he had been running for his life only moments ago.

Fireflies in a windstorm....

That phrase took flight through his mind, but he had no idea what it meant. When he tried to concentrate on it and make sense of it, a dull headache developed above his right eye.

Fireflies in a windstorm...

He groaned softly.

Between him and the dumpster, a shadow among shadows moved, quick and sinuous. Small but radiant green eyes regarded him with icy interest.

Frightened, Frank pushed up onto his knees. A thin, involuntary cry issued from him, almost less like a human sound than like the muted wail of a reed instrument.

The green-eyed observer scampered away. A cat. Just an ordinary black cat.

Frank got to his feet, swayed dizzily, and nearly fell over an object that had been on the blacktop beside him. Gingerly he bent down and picked it up: a flight bag made of supple leather, packed full, surprisingly heavy. He supposed it was his. He could not remember. Carrying the bag, he tottered to the dumpster and leaned against its rusted flank.

Looking back, he saw that he was between rows of what seemed to be two-story stucco apartment buildings. All of the windows were black. On both sides, the tenants’ cars were pulled nose-first into covered parking stalls. The queer yellow glow, sour and sulfurous, almost more like the product of a gas flame than the luminescence of an incandescent electric bulb, came from a streetlamp at the end of the block, too far away to reveal the details of the alleyway in which he stood.

As his rapid breathing slowed and as his heartbeat decelerated, he abruptly realized that he did not know who he was. He knew his name—Frank Pollard—but that was all. He did not know how old he was, what he did for a living, where he had come from, where he was going, or why. He was so startled by his predicament that for a moment his breath caught in his throat; then his heartbeat soared again, and he let his breath out in a rush.

Fireflies in a windstorm...

What the hell did that mean?

The headache above his right eye corkscrewed across his forehead.

He looked frantically left and right, searching for an object or an aspect of the scene that he might recognize, anything, an anchor in a world that was suddenly too strange. When the night offered nothing to reassure him, he turned his quest inward, desperately seeking something familiar in himself, but his own memory was even darker than the passageway around him.

Gradually he became aware that the scent of smoke had faded, replaced by a vague but nauseating smell of rotting garbage in the dumpster. The stench of decomposition filled him with thoughts of death, which seemed to trigger a vague recollection that he was on the run from someone—or something—that wanted to kill him. When he tried to recall why he was fleeing, and from whom, he could not further illuminate that scrap of memory; in fact, it seemed more an awareness based on instinct than a genuine recollection.

A puff of wind swirled around him. Then calm returned, as if the dead night was trying to come back to life but had managed just one shuddering breath. A single piece of wadded paper, swept up by that insufflation, clicked along the pavement and scraped to a stop against his right shoe.

Then another puff.

The paper whirled away.

Again the night was dead calm.

Something was happening. Frank sensed that these short-lived whiffs of wind had some malevolent source, ominous meaning.

Irrationally, he was sure that he was about to be crushed by a great weight. He looked up into the clear sky, at the bleak and empty blackness of space and at the malignant brilliance of the distant stars. If something was descending toward him, Frank could not see it.

The night exhaled once more. Harder this time. Its breath was sharp and dank.

He was wearing running shoes, white athletic socks, jeans, and a long-sleeved blue-plaid shirt. He had no jacket, and he could have used one. The air was not frigid, just mildly bracing. But a coldness was in him, too, a gelid fear, and he shivered uncontrollably between the cool caress of the night air and that inner chill.

The gust of wind died.

Stillness reclaimed the night.

Convinced that he had to get out of there—and fast—he pushed away from the dumpster. He staggered along the alley, retreating from the end of the block where the streetlamp glowed, into darker realms, with no destination in mind, driven only by the sense that this place was dangerous and that safety, if indeed safety could be found, lay elsewhere.

The wind rose again, and with it, this time, came an eerie whistling, barely audible, like the distant music of a flute made of some strange bone.

Within a few steps, as Frank became surefooted and as his eyes adapted to the murky night, he arrived at a confluence of passageways. Wrought-iron gates in pale stucco arches lay to his left and right.

He tried the gate on the left. It was unlocked, secured only by a simple gravity latch. The hinges squeaked, eliciting a wince from Frank, who hoped the sound had not been heard by his pursuer.

By now, although no adversary was in sight, Frank had no doubt that he was the object of a chase. He knew it as surely as a hare knew when a fox was in the field.

The wind huffed again at his back, and the flutelike music, though barely audible and lacking a discernible melody, was haunting. It pierced him. It sharpened his fear.

Beyond the black iron gate, flanked by feathery ferns and bushes, a walkway led between a pair of two-story apartment buildings. Frank followed it into a rectangular courtyard somewhat revealed by low-wattage security lamps at each end. First-floor apartments opened onto a covered promenade; the doors of the second-floor units w

ere under the tile roof of an iron-railed balcony. Lightless windows faced a swath of grass, beds of azaleas and succulents, and a few palms.

A frieze of spiky palm-frond shadows lay across one palely illuminated wall, as motionless as if they were carved on a stone entablature. Then the mysterious flute warbled softly again, the reborn wind huffed harder than before, and the shadows danced, danced. Frank’s own distorted, dark reflection whirled briefly over the stucco, among the terpsichorean silhouettes, as he hurried across the courtyard. He found another walkway, another gate, and ultimately the street on which the apartment complex faced.

It was a side street without lampposts. There, the reign of the night was undisputed.

The blustery wind lasted longer than before, churned harder. When the gust ended abruptly, with an equally abrupt cessation of the unmelodic flute, the night seemed to have been left in a vacuum, as though the departing turbulence had taken with it every wisp of breathable air. Then Frank’s ears popped as if from a sudden altitude change; as he rushed across the deserted street toward the cars parked along the far curb, air poured in around him again.

He tried four cars before finding one unlocked, a Ford. Slipping behind the wheel, he left the door open to provide some light.

He looked back the way he had come.

The apartment complex was dead-of-the-night still. Wrapped in darkness. An ordinary building yet inexplicably sinister.

No one was in sight.

Nevertheless, Frank knew someone was closing in on him.

He reached under the dashboard, pulled out a tangle of wires, and hastily jump-started the engine before realizing that such a larcenous skill suggested a life outside of the law. Yet he didn’t feel like a thief. He had no sense of guilt and no antipathy for—or fear of—the police. In fact, at the moment, he would have welcomed a cop to help him deal with whoever or whatever was on his tail. He felt not like a criminal, but like a man who had been on the run for an exhaustingly long time, from an implacable and relentless enemy.

As he reached for the handle of the open door, a brief pulse of pale blue light washed over him, and the driver’s-side windows of the Ford exploded. Tempered glass showered into the rear seat, gummy and minutely fragmented. Since the front door was not closed, that window didn’t spray over him; instead, most of it fell out of the frame, onto the pavement.

Yanking the door shut, he glanced through the gap where the glass had been, toward the gloom-enfolded apartments, saw no one.

Frank threw the Ford in gear, popped the brake, and tramped hard on the accelerator. Swinging away from the curb, he clipped the rear bumper of the car parked in front of him. A brief peal of tortured metal rang sharply across the night.

But he was still under attack: A scintillant blue light, at most one second in duration, lit up the car; over its entire breadth the windshield crazed with thousands of jagged lines, though it had been struck by nothing he could see. Frank averted his face and squeezed his eyes shut just in time to avoid being blinded by flying fragments. For a moment he could not see where he was going, but he didn’t let up on the accelerator, preferring the danger of collision to the greater risk of braking and giving his unseen enemy time to reach him. Glass rained over him, spattered across the top of his bent head; luckily, it was safety glass, and none of the fragments cut him.

He opened his eyes, squinting into the gale that rushed through the now empty windshield frame. He saw that he’d gone half a block and had reached the intersection. He whipped the wheel to the right, tapping the brake pedal only lightly, and turned onto a more brightly lighted thoroughfare.

Like Saint Elmo’s fire, sapphire-blue light glimmered on the chrome, and when the Ford was halfway around the comer, one of the rear tires blew. He had heard no gunfire. A fraction of a second later, the other rear tire blew.

The car rocked, slewed to the left, began to fishtail.

Frank fought the steering wheel.

Both front tires ruptured simultaneously.

The car rocked again, even as it glided sideways, and the sudden collapse of the front tires compensated for the leftward slide of the rear end, giving Frank a chance to grapple the spinning steering wheel into submission.

Again, he had heard no gunfire. He didn’t know why all of this was happening—yet he did.

That was the truly frightening part: On some deep subconscious level he did know what was happening, what strange force was swiftly destroying the car around him, and he also knew that his chances of escaping were poor.

A flicker of twilight blue ...

The rear window imploded. Gummy yet prickly wads of safety glass flew past him. Some smacked the back of his head, stuck in his hair.

Frank made the comer and kept going on four flats. The sound of flapping rubber, already shredded, and the grinding of metal wheel rims could be heard even above the roar of the wind that buffeted his face.

He glanced at the rearview mirror. The night was a great black ocean behind him, relieved only by widely spaced streetlamps that dwindled into the gloom like the lights of a double convoy of ships.

According to the speedometer, he was doing thirty miles an hour just after coming out of the turn. He tried to push it up to forty in spite of the ruined tires, but something clanged and clinked under the hood, rattled and whined, and the engine coughed, and he could not coax any more speed out of it.

When he was halfway to the next intersection, the headlights either burst or winked out. Frank couldn’t tell which. Even though the streetlamps were widely spaced, he could see well enough to drive.

The engine coughed, then again, and the Ford began to lose speed. He didn’t brake for the stop sign at the next intersection. Instead he pumped the accelerator but to no avail.

Finally the steering failed too. The wheel spun uselessly in his sweaty hands.

Evidently the tires had been completely torn apart. The contact of the steel wheel rims with the pavement flung up gold and turquoise sparks.

Fireflies in a windstorm....

He still didn’t know what that meant.

Now moving about twenty miles an hour, the car headed straight toward the right-hand curb. Frank tramped the brakes, but they no longer functioned.

The car hit the curb, jumped it, grazed a lamppost with a sound of sheet metal kissing steel, and thudded against the bole of an immense date palm in front of a white bungalow. Lights came on in the house even as the final crash was echoing on the cool night air.

Frank threw the door open, grabbed the leather flight bag from the seat beside him, and got out, shedding fragments of gummy yet splintery safety glass.

Though only mildly cool, the air chilled his face because sweat trickled down from his forehead. He could taste salt when he licked his lips.

A man had opened the front door of the bungalow and stepped onto the porch. Lights flicked on at the house next door.

Frank looked back the way he had come. A thin cloud of luminous sapphire dust seemed to blow through the street. As if shattered by a tremendous surge of current, the bulbs in the streetlamps exploded along the two blocks behind him, and shards of glass, glinting like ice, rained on the blacktop. In the resultant gloom, he thought he saw a tall, shadowy figure, more than a block away, coming after him, but he could not be sure.

To Frank’s left, the guy from the bungalow was hurrying down the walk toward the palm tree where the Ford had come to rest. He was talking, but Frank wasn’t listening to him.

Clutching the leather satchel, Frank turned and ran. He was not sure what he was running from, or why he was so afraid, or where he might hope to find a haven, but he ran nonetheless because he knew that if he stood there only a few seconds longer, he would be killed.

2

THE WINDOWLESS rear compartment of the Dodge van was illuminated by tiny red, blue, green, white, and amber indicator bulbs on banks of electronic surveillance equipment but primarily by the soft green glow from the two computer screens, which made that claustr

ophobic space seem like a chamber in a deep-sea submersible.

Dressed in a pair of Rockport walking shoes, beige cords, and a maroon sweater, Robert Dakota sat on a swivel chair in front of the twin video display terminals. He tapped his feet against the floorboards, keeping time, and with his right hand he happily conducted an unseen orchestra.

Bobby was wearing a headset with stereo earphones and with a small microphone suspended an inch or so in front of his lips. At the moment he was listening to Benny Goodman’s “One O’Clock Jump,” the primo version of Count Basie’s classic swing composition, six and a half minutes of heaven. As Jess Stacy took up another piano chorus and as Harry James launched into the brilliant trumpet stint that led to the most famous rideout in swing history, Bobby was deep into the music.

But he was also acutely aware of the activity on the display terminals. The one on the right was linked, via microwave, with the computer system at the Decodyne Corporation, in front of which his van was parked. It revealed what Tom Rasmussen was up to in those offices at 1:10 Thursday morning: no good.

One by one, Rasmussen was accessing and copying the files of the software-design team that had recently completed Decodyne’s new and revolutionary word-processing program, “Whizard.” The Whizard files carried well-constructed lockout instructions-electronic drawbridges, moats, and ramparts. Tom Rasmussen was an expert in computer security, however, and there was no fortress that he could not penetrate, given enough time. Indeed, if Whizard had not been developed on a secure in-house computer system with no links to the outside world, Rasmussen would have slipped into the files from beyond the walls of Decodyne, via a modem and telephone line.

Ironically, he had been working as the night security guard at Decodyne for five weeks, having been hired on the basis of elaborate—and nearly convincing—false papers. Tonight he had breached Whizard’s final defenses. In a while he would walk out of Decodyne with a packet of floppy diskettes worth a fortune to the company’s competitors.

“One O’Clock Jump” ended.

Into the microphone Bobby said, “Music stop.”

That vocal command cued his computerized compact-disc system to switch off, opening the headset for communication with Julie, his wife and business partner.

“You there, babe?”

From her surveillance position in a car at the farthest end of the parking lot behind Decodyne, she had been listening to the same music through her own headset. She sighed. “Did Vernon Brown ever play better trombone than the night of the Carnegie concert?”

“What about Krupa on the drums?”

“Auditory ambrosia. And an aphrodisiac. The music makes me want to go to bed with you.”

“Can’t. Not sleepy. Besides, we’re being private detectives, remember?”

“I like being lovers better.”

“We don’t earn our daily bread by making love.”

“I’d pay you,” she said.

“Yeah? How much?”

“Oh, in daily-bread terms ... half a loaf.”

“I’m worth a whole loaf.”

Julie said, “Actually, you’re worth a whole loaf, two croissants, and a bran muffin.”

She had a pleasing, throaty, and altogether sexy voice that he loved to listen to, especially through headphones, when she sounded like an angel whispering in his ears. She would have been a marvelous big-band singer if she had been around in the 1930s and ’40s—and if she had been able to carry a tune. She was a great swing dancer, but she couldn’t croon worth a damn; when she was in the mood to sing along with old recordings by Margaret Whiting or the Andrews Sisters or Rosemary Clooney or Marion Hutton, Bobby had to leave the room out of respect for the music.

She said, “What’s Rasmussen doing?”