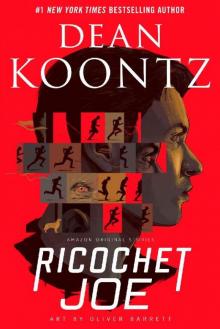

Ricochet Joe

Dean Koontz

Two Ways to Read

This book features art and animation specifically designed to enhance this story. You can control your experience on compatible devices by using the Show Media option in the Aa menu.

1

FLASH FORWARD

As warm as May in March, Saturday had begun on a light note, with useful work and the promise of romance, and Joe could never have imagined that in mere hours he would arrive at this darkest moment of his life. There was an old song that had been a hit more than once over the years, twice before Joe had been born. He thought of it now: “You Always Hurt the One You Love.” His eyes flooded with tears as he shot her dead.

2

AN ORDINARY JOE

Nothing remarkable happened to Joe Mandel until the winter that he was eighteen, when over the course of one day, more interesting, strange, and perilous events befell him than most people experience in a lifetime. Having floated through so many tranquil years free of adversity, he was ill prepared for his encounters with what his maternal grandmother, Dulcie Rockwell, called “Dedicated Practitioners of Evil,” or DPEs.

Neither tall nor short, Joe stood five ten in his stocking feet and just a little bit shorter when barefoot. Neither fat nor thin, he weighed a hundred sixty pounds. Brown hair. Brown eyes. Neither movie-star handsome nor hideously ugly, he had a pleasant face and a winsome smile. He always wore jeans and T-shirts, except when he wore jeans and flannel shirts.

Everybody liked Joe well enough, and nobody hated him. His mother had died of cancer so long ago that he had no memory of her. His father loved Joe to the extent that he was capable, but being a low-key individual not given to intense emotions, he expressed his love more often with pats on the head and affectionate smiles than with kisses and extravagant proclamations of devotion.

Grandma Dulcie often kissed Joe on the forehead or the cheek, and she told him she loved him “half to death,” which to him always seemed like an odd way to express love. But Grandma Dulcie was what his dad called “a character.” If flamboyance was an inheritable trait, Dulcie evidently had gotten all of it that had been allotted to three generations of the Mandel and Rockwell families.

Joe lived in Little City, which was named after its founder, Thomas Little. Little City wasn’t really a city. It was more like a big town, with twenty thousand citizens. There had been fewer than four hundred residents when Thomas Little founded the place, but he had been a man with big dreams and no regard for the truth.

Saturday, the eleventh day of March, interesting things began to happen to this ordinary Joe. During the week, he attended classes at Little Junior College, which Grandma Dulcie said was “a stupid redundant name,” where he had begun to prepare himself to be either an English teacher or an advertising copywriter, or maybe a destitute novelist. He wasn’t yet certain of his career, though he knew he didn’t want to be a dentist like his father, because looking too deeply into people’s mouths disturbed him. On weekends, Joe read novels or worked on one he was writing, but on the Saturday morning when his life changed, he was doing volunteer work in Central Park.

Joe was grateful to have grown up in a quiet, charming town like Little City. To express his gratitude, he often gave his time to help a local organization called Volunteers for a Better Future.

Grandma Dulcie said that Volunteers for a Better Future sounded like a platoon of time travelers going to the year 2100 to fight in a war against invaders from another planet. What they actually did was mostly pick up trash.

Central Park wasn’t in the center of Little City but on the west side of town, behind the public library. In Joe’s experience, his fellow citizens were largely quiet and pleasant, like the town, but a surprising number were also prodigious litterers. A team of six volunteers, each armed with a heavy-duty plastic trash bag and a stick with a nail on the end, quartered the park to rid it of candy bar wrappers and discarded paper cups and empty cigarette packs and crumpled beer cans and an infinite variety of other trash.

A new volunteer was on duty, a strikingly pretty girl named Portia. She was so nice to look at that Joe twice stabbed his left foot when he thought he was spearing a bit of litter, though neither wound was serious enough to require a tetanus shot. He had no intention of asking Portia for a date. She was so pretty, so sexy, and so elegant that she was not likely to date a guy who didn’t know if he should be an English teacher or a destitute writer.

Although he had no idea that his life was about to be turned upside down and inside out and topsy-turvy, the change happened in an instant when he picked up an empty pint bottle of rum to throw it in his trash bag. Joe was for the most part soft-spoken, though he raised his voice when he said, “Corvette!”

Ten feet to his left, Portia looked up from an empty condom packet pierced on the end of her litter stick and said, “Corvette?”

Joe could not explain why he’d spoken the word with such force, or why he had spoken it at all. Nevertheless, he might have seized the moment to open a conversation with the girl; but that was not to be just then. What was to be astonished him: he dropped the empty rum bottle in his trash bag, dropped the bag, and ran off toward the library with his litter stick raised like a warrior’s pike.

He didn’t know where he might be going, but his bewilderment did not bring him to a halt. He felt compelled to go wherever his feet took him, like a man possessed and harried hither and yon by a demonic spirit, except there was no stink of sulfur, no cursing in Latin, no sense of being occupied by anything evil or even naughty.

Hither and yon actually proved to be the street beyond the library, where he came to a halt beside a parked sports car. A red Corvette.

Joe admired Corvettes, but he didn’t want one. The car seemed too flashy for him. He drove a secondhand Honda.

That might have been the end of the weirdness, except that he felt compelled to touch the Corvette. When he put a hand to it, two words escaped him—“Bus stop!”—and he was off again.

He raced into the street, in the middle of the block. Brakes screeched and horns blared as motorists strove not to run him down. He received a few suggestions in finger language, so rude that he thought the drivers must be from out of town.

Having crossed the street, he turned east and hurried past a series of quaint shops. Little City was a tourist destination in part because of its many specialty stores and the quaint shopping they provided.

The bus stop was at the end of the block. No one sat on the bench or stood waiting.

As he had touched the Corvette, so Joe also felt compelled to put his hand on the seat of the bench, with the consequence that he spoke again without volition: “Rats!”

Although his bewilderment had not diminished, had in fact grown, Joe remained clearheaded enough to recognize a pattern to these events. He was filled with disgust at the likelihood that he would next be compelled to find and snatch up a rat.

It must be said here that during this bizarre ordeal Joe Mandel did not once question his sanity. Neither was he as frightened as it might seem he ought to have been. He felt a rightness about what he was doing, even though to startled observers it appeared wrong.

He was well aware that other pedestrians regarded him with surprise and perplexity, although no one called for police or warned him to back off as he raced here and there with his litter stick. For one thing, he was a wholesome-looking young man with a winsome smile, which was sort of frozen on his face during this adventure, and for another thing, he kept the nail pointed skyward and clearly did not threaten anyone. No doubt some people thought he was merely fulfilling a hazing obligation to a junior-college fraternity or that he was stunti

ng for a YouTube audience.

At a small—and need it be said, quaint—shop selling glass and ceramic art, the window featured a display of hand-sculpted, fired, and hand-painted ceramic mice, not rats, of considerable cuteness, in all manner of costumes and scenes. Joe saw a man’s handprint on the window glass, and he knew that he should place his hand atop it, though the large print looked oily and unclean. On contact, he declared, “Shit!” and hurried onward.

The mice had not been rats, and they hadn’t even been flesh-and-blood mice, but Joe nevertheless dreaded that the filth he would soon be compelled to touch would prove to be the real thing.

At the corner, he pivoted ninety degrees while hardly slowing down, then ran a quarter of a block to a free community parking lot and sprinted among the vehicles until he discovered an elderly woman who had been knocked to the ground. A fierce man bent over her, struggling to wrench her purse from her hands, which he managed to do just as Joe arrived, breathless.

With his litter stick, Joe did not hesitate to prick the assailant’s hand.

The thief cried out—“Shit!”—and dropped the purse.

Although Joe Mandel possessed an admirable sense of civic duty, he fulfilled it largely through Volunteers for a Better Future, as well as by never littering, by never parking in red zones, and by paying his library fines promptly and without complaint. He had never considered becoming a vigilante in search of criminals to obstruct. Now that he found himself in exactly that situation, he didn’t much like being there.

His average height and average build and pleasant face and winsome smile did not seem adequate in a confrontation with a purse snatcher who was maybe six feet one, a hundred ninety pounds, with big hands. Under an oily mass of slicked-back hair, the criminal had a brutish face, rum on his breath, and murder in his eyes.

Where the big knife came from, Joe couldn’t say. The guy seemed to pluck it out of thin air, though it must have been in one pocket or another. After all, if he had been a good enough magician to make switchblade knives appear from nowhere, he would not have needed to knock down old ladies to get drinking money.

“You piss me off, pretty boy,” declared the purse snatcher.

Joe said, “Sorry, but I had to.”

“Know what I do to people who piss me off?”

“I can sort of imagine.”

“I cut their guts out.”

Joe seriously doubted that the creep cut out the intestines of everyone who pissed him off, because he looked like a guy who would be pissed off at someone every half hour. No one could get away with public disembowelments more than, say, two or three times.

Nevertheless, Joe broke into a sweat when the thug lurched forward with a knife that appeared to have been lovingly stropped to razor sharpness. He danced backward and poked at his adversary with the litter stick, acutely aware that he was inadequately armed.

The purse snatcher laughed and feinted left, feinted right, easing closer. But he choked on his laugh and staggered backward when another litter stick flew through the air and stuck in the hollow of his throat. He dropped his switchblade and pulled the nail-tipped spear out of himself and threw it down and ran off, gagging, spitting.

The lovely Portia stepped past Joe, kicked the switchblade into a nearby storm drain, and said to the elderly woman, “Are you all right, Mrs. Cortland?”

As the senior citizen got to her feet, she said, “Yes, dear. I think he was just a common criminal.”

“I think so, too, coming at you in public like that. But you better be careful.” Portia put one hand on Joe’s shoulder. “By the way, this is Joe Mandel. Joe, this is Ida Cortland.”

“Thank you for being so brave, young man,” Mrs. Cortland said.

He blushed. “I wasn’t, really. I just sort of like got caught up in the moment.”

To Portia, Ida Cortland said, “I’ll call in a description of that purse-grabbing bastard, so the chief can try to find him and determine if he’s as common as he seems.”

3

ICE CREAM AND PAINFUL LOSS

The city council and the many business owners of Little City, recognizing that the world was growing darker and more dysfunctional every year, had worked together to provide anxious tourists with a destination that reminded them of a much earlier era. Therefore, on the main street, under the jacaranda trees and the palm trees, along the cobblestone sidewalk, among the quaint shops and the genteel galleries and the wondrous little cafés, there was even a malt shop with a 1950s decor and waitresses wearing white uniforms and pink hats and pink shoes. To even the most critical eye, every detail of the establishment appeared historically correct—except that there were no ashtrays on the tables.

Both Joe and Portia would have chased their adventure with a more fortifying beverage if they had been of drinking age, but as they were both eighteen, they settled for a back booth in the malt shop, ordering a chocolate-ice-cream soda for him and a cherry-ice-cream soda for her.

“So nothing like that ever happened to you before?” she asked.

“Did I look like I knew what I was doing?”

“I wish I could say yes.”

The experience seemed almost like something that he had dreamed, and he was surprised that it hadn’t left him more badly shaken. In fact, a curious sense of well-being had settled over him the moment that the purse snatcher had run off, as if he’d been given antianxiety medication.

“I must have looked crazed.”

“Man, you were like some pinball ricocheting from flipper to buzzer to bell.”

Joe liked the way that Portia stirred her drink to make the ice cream melt faster, how she scooped the creamy foam off the top of the soda, how she ate it with the slightest smacking of her lips.

He said, “Why on earth did you follow me through all of that?”

“Who wants to spend Saturday stabbing litter?”

“Volunteers for a Better Future,” he said.

“I didn’t volunteer. I was dragooned.”

“Dragooned by whom?”

“Who the hell says whom anymore?”

“I might be a writer someday.”

“Oh, I hope not. You seem so nice.”

Joe watched her drawing the pink cherry-flavored slush through her straw. Her lips puckered precisely, and her cheeks dimpled with the suction, and her throat pulsed with each swallow. Joe was not mechanically inclined. Working on car engines and that kind of thing held no appeal for him. But he was riveted by the mechanical process of Portia consuming the cherry-ice-cream soda.

“What’s wrong with writers?” he asked.

“A lot of them hate the world and want to change it, build Utopia.”

“I don’t.”

“Good. Because utopias always turn out to be one version of hell or another.”

“I just want to tell good stories. Or write advertising copy.”

“I am dazzled by your commitment to literature. So what was it that happened to you out there? Are we talking psychic phenomena? Are you some kind of mutant?”

“I’m not one of the X-Men.”

“You’re no Wolverine, for sure. But you’re something.”

“No, not me.” Again his equanimity surprised him. “It was just a two-headed-calf thing.”

“Are you going to drink your ice-cream soda, or just have erotic fantasies while you watch me drink mine?”

“I could be happy either way,” he said, but he turned his attention to his soda.

Portia propped one elbow on the table, rested her chin in the palm of her hand, watched him for a moment, and said, “You do that pretty well yourself.”

He said, “Who dragooned you into volunteering?”

“Chief Montclair.�

�

“The police chief?”

“Well, he’s not an Indian chief. He was upset with me.”

“That’s not good.”

“Oh, he’s been upset with me at least since my first day in elementary school.”

“You got in trouble with the cops when you were just six? How?”

“I stripped off my clothes and ran naked through the school.”

Joe took a break from his ice-cream soda to consider what she had said. In his mind’s eye, she was eighteen in first grade. “Why would you do that?”

“I didn’t want to be there.”

“An extreme strategy.”

“It worked a few times. Then it didn’t. So I bit the bullet for twelve years of tedium—otherwise known as school.”

“I liked school,” he said.

“I’m not stupid, okay? I got top grades. They just make it all so boring. I have a low tolerance for boring.”

“So why did Chief Montclair make you volunteer?”

“Too many speeding tickets. Either I had to volunteer, or he’d take away my driver’s license.”

“He can’t do that. Can he do that?”

She shrugged. “He’s not just the police chief. He’s also my father, and I still live at home.”

“You’re Portia Montclair.”

“Wow, you put it together just like that.”

She returned to her cherry-ice-cream soda, and for a minute or so, they both enjoyed her enjoyment of it.

She said, “You’ll have to meet my dad. He’s a hard-nosed cop, but you’ll like him.”

“Your mom must be very pretty. I mean, well, ’cause you are.”