Dragonfly

Dean Koontz

Dean Koontz – Dragonfly

[Version 2.0 by BuddyDk – august 9 2003]

[Easy read, easy print]

[Completely new scan]

". . . This special project . . . centers on an as yet unknown Chinese citizen who has been made, quite literally, into a walking bomb casing for a chemical-biological weapon that could kill tens of thousands of his people. The Committeemen have a code name for him— Dragonfly."

"Berlinson has no idea who the carrier is?"

"All he knew was that Dragonfly is a Chinese citizen who was in the United States or Canada sometime between New Year's Day and February fifteenth of this year."

"How many suspects are there?"

"Five hundred and nine."

DRAGONFLY

White-knuckle suspense in the shock

novel of the year!

"ONE OF THE BEST." —Bestsellers

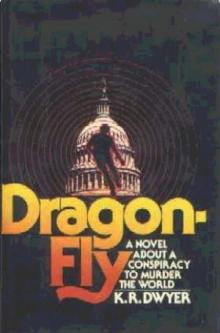

BOOKS BY K. R. DWYER

Chase

Shattered

Dragonfly

DRAGONFLY

K. R. Dwyer

BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK

Copyright © 1975 by K. R. Dwyer

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Ballantine Books of Canada, Ltd., Toronto, Canada.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-9877

ISBN 0-345-25140-7-175

This edition published by arrangement with

Random House, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Ballantine Books Edition: August, 1976

To Bill Pronzini and Barry Malzberg—

two-thirds of a friendship that keeps

the telephone company solvent

ONE

ONE

Carpinteria, California

When he woke shortly after three o'clock Wednesday morning, Roger Berlinson thought he heard strange voices in the house. A quick word or two. Then silence. An unnatural silence? He was clutching the sweat-dampened sheets so tightly that his arms ached all the way to his shoulders. He let go of the sodden linens and worked the cramps out of his fingers. Trembling, he reached out with his right hand, pulled open the top drawer of the nightstand, and picked up the loaded pistol that was lying there. In the moon-dappled darkness he performed a blind man's exploration of the gun until he was certain that both of the safeties were switched off. Then he lay perfectly still, listening.

The house was on a low bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. In the empty early-morning hours the only sounds at the windows were the voices of nature: the soughing of a southwesterly wind, distant thunder, and the steady rush of the tide. Inside the house there were no voices, no squeaking floorboards, nothing but Berlinson's own heavy breathing.

It's just your imagination, he told himself. Putney is on the midnight-to-eight duty. He's downstairs in the kitchen right now, monitoring the alarm systems. If there was any trouble, he'd take care of it before it got serious. Putney's a damned good man; he doesn't make mistakes. So we're safe. There's absolutely no danger. You've had another nightmare, that's all.

Nevertheless, Berlinson threw back the covers and got out of bed and stepped into his felt-lined slippers. His moist pajamas clung to his back and thighs; chills swept down his spine.

He held the gun at his side. In an instant he could bring it up, swivel, and fire in any direction. He was well trained.

His wife, Anna, stirred in her sleep, but thanks to her nightly sedative, did not wake up. She turned over on her stomach and mumbled into the pillow and sighed.

Quietly, cautiously, Berlinson crossed the room to the open door and eased into the second-floor hall. The corridor was much darker than the bedroom, for it had only one window at the far end. Berlinson had just enough light to see that everything was as it should be: the telephone table was at the head of the stairs; a large vase full of straw flowers stood on the window bench at the end of the hall; and the flimsy curtains billowed in the draft from the air-conditioning vent high on the right-hand wall.

Berlinson walked past the staircase and on down the hall to his son's room. Peter was in bed, lying on his side, facing the door, snoring softly. Under the circumstances, no one but a teenager, with an appetite for sleep as great as his appetite for food and activity, could possibly have slept so soundly, so serenely, without the aid of a drug.

There you are, Berlinson told himself. Everyone's safe. There's no danger here. No one from the agency can possibly know where you are. No one. Except McAlister. Well, what about McAlister? Hell, he's on your side. You can trust him. Can't you? Yes. Implicitly. So there you are.

However, instead of returning straight to bed, he went to the stairs and down to the first floor. The living room was full of dark, lumpish furniture. A grandfather clock ticked in a far corner; its pendulum provided the only movement, the only noise, the only sign of life, either animal or mechanical, in the room. The dining room was also deserted. The many-paned glass doors of the china hutch—and the dishes shelved beyond the glass—gleamed in the eerie orange light. Berlinson went into the kitchen, where the Halloweenish glow, the only light in the house, emanated from several expensive, complicated machines that stood on the Formica-topped breakfast table.

Putney was gone.

"Joe?"

There was no reply.

Berlinson went to look at the monitors—and he found Joseph Putney on the other side of the table. The night guard was sprawled on the floor, on his back, his arms out to his sides as if he were trying to fly, a bullet hole in the center of his forehead. His eyes glittered demonically in the orange light from the screens.

Now hold on, keep control, keep cool, Berlinson thought as he automatically crouched and turned to see if anyone had moved in behind him.

He was still alone.

Glancing at the four repeater screens of the infrared alarm system which protected the house, Berlinson saw that the machines were functioning and had detected no enemies. All approaches to the house—north, east, south, and west from the beach—were drawn in thermal silhouette on these monitors. No heat-producing source, neither man nor animal nor machine, could move onto the property without immediately registering on the system, setting off a loud alarm, and thereby alerting the entire household.

Yet Putney was dead.

The alarm system had been circumvented. Someone was in the house. His cover was blown; the agency had come after him. In the morning Anna would find him just as he had found Putney . . .

No, dammit! You're a match for them. You're as good and as fast as they are: you're one of them, for Christ's sake, a snake from the same nest. You'll get Anna and Petey out of here, and you'll go with them.

He moved along the wall, back toward the dining room, through the archway, past the hutch, into the living room, to the main stairs. He studied the darkness at the top of the staircase. The man—or men— who had killed Putney might be up there now. Probably was. But there was no other way Berlinson could reach his family. He had to risk it. Keeping his back to the wall, alternately glancing at the landing above and at the living room below, expecting to be caught in a crossfire at any moment, he went up step by step, slowly, silently.

Unmolested, he covered sixteen of the twenty risers, then stopped when he saw that there was someone sitting on the top step and leaning against the banister. He almost opened fire, but even in these deep shadows, the other man was somehow familiar. When there was no challenge made, no threat, no movement at all, Berlinson inched forward—and discovered that the man on the steps was Peter, his son. The front of Petey's pajama shirt was soaked with blood; he had been shot in the throat.

N

o! Dammit, no! Berlinson thought, weeping, shuddering, cursing, sick to his stomach. Not my family, damn you. Me, but not my family. That's the rule. That's the way the game's played. Never the family. You crazy sonsofbitches! No, no, no!

He stumbled off the steps and ran across the hall, crouching low, the pistol held out in front of him. He fell and rolled through the open bedroom door, came up onto his knees fast, and fired twice into the wall beside the door.

No one was there.

Should have been, dammit. Should have been someone there.

He crawled around behind the bed, using it as a shield. Cautiously, he rose up to see if Anna was all right. In the moonlight the blood on the sheets looked as viscous and black as sludge oil.

At the sight of her, Berlinson lost control of himself. "Come out!" he shouted to the men who must now be in the corridor, listening, waiting to burst in on him. "Show yourselves, you bastards!"

On his right the closet door was flung open.

Berlinson fired at it.

A man cried out and fell full length into the room. His gun clattered against the legs of a chair.

"Roger!"

Berlinson whirled toward the voice which came from the hall door. A silenced pistol hissed three times. Berlinson collapsed onto the bed, clutching at the covers and at Anna. Absurdly, he thought: I can't be dying. My life hasn't flashed before my eyes. I can't be dying if my life hasn't

TWO

Washington, D.C.

When the doorbell rang at eleven o'clock that morning, David Canning was studying the leaves of his schefflera plant for signs of the mealybugs he had routed with insecticide a week ago. Seven feet tall and with two hundred leaves, the schefflera was more accurately a tree than a house plant. He had purchased it last month and was already as attached to it as he had once been, as a boy, to a beagle puppy. The tree offered none of the lively companionship that came with owning a pet; however, Canning found great satisfaction in caring for it—watering, misting, sponging, spraying with Malathion—and in watching it respond with continued good health and delicate new shoots.

Satisfied that the mealybugs had not regenerated, he went to the door, expecting to find a salesman on the other side.

Instead, McAlister was standing in the hall. He was wearing a five-hundred-dollar raincoat and was just pulling the hood back from his head. He was alone, and that was unusual; he always traveled with one or two aides and a bodyguard. McAlister glanced at the round magnifying glass in Canning's hand, then up at his face. He smiled. "Sherlock Holmes, I presume."

"I was just examining my tree," Canning said.

"You're a wonderful straight man. Examining your tree?"

"Come in and have a look."

McAlister crossed the living room to the schefflera. He moved with grace and consummate self-assurance. He was slender: five ten, a hundred forty pounds. But he was in no way a small man, Canning thought. His intelligence, cunning, and self-possession were more impressive than size and muscle. His oblong face was square-jawed and deeply tanned. Inhumanly blue eyes, an electrifying shade that existed nowhere else beyond the technicolor fantasies on a Cinema-Scope screen, were accentuated by old-fashioned hornrimmed glasses. His lips were full but bloodless. He looked like a Boston Brahmin, which he was: at twenty-one he had come into control of a two-million-dollar trust fund. His dark hair was gray at the temples, an attribute he used, as did bankers and politicians, to make himself seem fatherly, experienced, and trustworthy. He was experienced and trustworthy; but he was too shrewd and calculating ever to seem fatherly. In spite of his gray hair he appeared ten years younger than his fifty-one. Standing now with his fists balled on his hips, he had the aura of a cocky young man.

"By God, it is a tree!"

"I told you," Canning said, joining him in front of the schefflera. He was taller and heavier than McAlister: six one, a hundred seventy pounds. In college he had been on the basketball team. He was lean, almost lanky, with long arms and large hands. He was wearing only jeans and a blue T-shirt, but his clothes were as neat, clean, and well pressed as were McAlister's expensive suit and coat. Everything about Canning was neat, from his full-but-not-long razor-cut hair to his brightly polished loafers.

"What's it doing here?" McAlister asked.

"Growing."

"That's all?"

"That's all I ask of it."

"What were you doing with the magnifying glass?"

"The tree had mealybugs. I took care of them, but they can come back. You have to check every few days for signs of them."

"What are mealybugs?"

Canning knew McAlister wasn't just making small talk. He had a bottomless curiosity, a need to know something about everything; yet his knowledge was not merely anecdotal, for he knew many things well. A lunchtime conversation with him could be fascinating. The talk might range from primitive art to current developments in the biological sciences, and from there, to pop music to Beethoven to Chinese cooking to automobile comparisons to American history. He was a Renaissance man—and he was more than that.

"Mealybugs are tiny," Canning said. "You need a magnifying glass to see them. They're covered with white fuzz that makes them look like cotton fluff. They attach themselves to the undersides of the leaves, along the leaf veins, and especially in the green sheaths that protect new shoots. They suck the plant's juices, destroy it."

"Vampires."

"In a way."

"I meet them daily. In fact, I want to talk to you about mealybugs."

"The human kind."

"That's right." He stripped off his coat and almost dropped it on a nearby chair. Then he caught himself and handed it to Canning, who had a neatness fetish well known to anyone who had ever worked with him. As Canning hung the coat in the carefully ordered foyer closet, McAlister said, "Would it be possible to fix some coffee, David?"

"Already done," he said, leading McAlister into the kitchen. "I made a fresh pot this morning. Cream? Sugar?"

"Cream," McAlister said. "No sugar."

"A breakfast roll?"

"Yes, that would be nice. I didn't have time to eat this morning."

Motioning to the table that stood by the large mullioned window, Canning said, "Sit down. Everything'll be ready in a few minutes."

Of the four available chairs McAlister took that one which faced the living-room archway and which put him in a defensible corner. He chose not to sit with his back to the window. Instead, the glass was on his right side, so that he could look through it but probably could not be seen by anyone in the gardened courtyard outside.

He's a natural-born agent, Canning thought.

But McAlister would never spend a day in the field. He always started at the top—and did his job as well as he could have done had he started at the bottom. He had served as Secretary of State during the previous administration's first term, then moved over to the White House, where he occupied the chief advisory post during half of the second term. He had quit that position when, in the midst of a White House scandal, the President had asked him to lie to a grand jury. Now, with the opposition party in power, McAlister had another important job, for he was a man whose widely recognized integrity made it possible for him to function under Republicans or Democrats. In February he had been appointed to the directorship of the Central Intelligence Agency, armed with a Presidential mandate to clean up that dangerously autonomous, corrupt organization. The McAlister nomination was approved swiftly by the Senate, one month to the day after the new President was inaugurated. McAlister had been at the agency—cooperating with the Justice Department in exposing crimes that had been committed by agency men—ever since the end of February, seven headline-filled months ago.

Canning had been in this business more than six months. He'd been a CIA operative for twenty years, ever since he was twenty-five. During the cold war he carried out dozens of missions in the Netherlands, West Germany, East Germany, and France. He had gone secretly behind the Iron Curtain on seven separate occasions

, usually to bring out an important defector. Then he was transferred Stateside and put in charge of the agency's Asian desk, where the Vietnam mess required the attendance of a man who had gone through years of combat, both hot and cold. After fourteen months in the office, Canning returned to field work and established new CIA primary networks in Thailand, Cambodia, and South Vietnam. He operated easily and well in Asia. His fastidious personal habits, his compulsive neatness, appealed to the middle-and upper-class Asians who were his contacts, for many of them still thought of Westerners as quasi-barbarians who bathed too seldom and carried their linen-wrapped snot in their hip pockets. Likewise, they appreciated Canning's Byzantine mind, which, while it was complex and rich and full of classic oriental cunning, was ordered like a vast file cabinet. Asia was, he felt, the perfect place for him to spend the next decade and a half in the completion of a solid, even admirable career.

However, in spite of his success, the agency took him off his Asian assignment when he was beginning his fifth year there. Back home he was attached to the Secret Service at the White House, where he acted as a special consultant for Presidential trips overseas. He helped to define the necessary security precautions in those countries that he knew all too well.

McAlister chaired these Secret Service strategy conferences, and it was here that Canning and he had met and become friends of a sort. They had kept in touch even after McAlister resigned from the White House staff—and now they were working together again. And again McAlister was the boss, even though his own experience in the espionage circus was far less impressive than Canning's background there. But then, McAlister would be boss wherever he worked; he was born to it. Canning could no more resent that than he could resent the fact that grass was green instead of purple. Besides, the director of the agency had to deal daily with politicians, a chore of which Canning wanted no part.