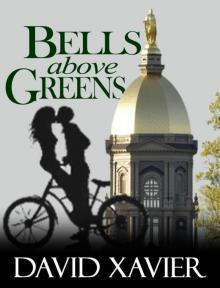

Bells Above Greens

David Xavier

Bells Above Greens

By David Xavier

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Chapter One

The bus did not slow as it approached the narrow bridge to Fort Wayne. The driver leaned forward over the steering wheel, taking the small dip with the confidence of having done so many times before. His seat was nothing more than a foam pad on a large spring. I watched the back of his head submerge and resurface in front of me, the spring croaking beneath him. A whip-curve of crows jumped into flight from the bridge rail from near to far, and I sat with my forehead pressed to the window.

Young men filled the hard seats around me, each with excitement beating inside their chests like enormous hearts, their ankles tapping below them, and although I was happy to be home I was content to sit and be the last man off. I would have fought for the front of the line if I had known, because when I stepped off the bus and she nearly kissed me by mistake, her fingers around the back of my head and her lips close enough that I could smell the lipstick, the long drive had been worth taking for the surprise greeting alone.

The soldiers lowered the windows as the road turned from gravel to pavement and the dust faded behind us. Squids of arms filled the windows as the soldiers whistled catcalls to the girls who stood waiting behind the gates. A parade of waving red fingernails on jumping arms returned the excitement.

“Window.” One of the soldiers tapped my arm.

I stood to open the window, the stiff latch requiring an open-palmed encouragement, and sat back down with my forehead against the lower half of glass. A squinty enlisted man with a baby face waved our driver through with a salute, the bus lurching as it shifted into another gear.

“They recruiting at the grammar schools now?” The soldier leaned over me to look out the window, chewing a piece of gum with all his teeth.

I pushed him back with my forearm to his chest. “How old are you?”

“Nineteen,” he said.

“When did you sign up?”

“I was seventeen.” The soldier looked around, nodding to the other men. “Had to lie to Uncle Sam.”

“How old do you think he is?” I nodded sideways to the window.

“Still innocent in his dreams,” he shrugged. He looked around and spoke aloud. “Sergeant sewed his name in his skivvies.”

There was a faint laugh from somewhere in front of us. The soldier started to repeat himself in a louder voice but let it drop. Everyone stood at once to reach for their bags on the overhead shelves and make a surge to the front of the bus. As soon as they made eye contact with their girls outside everything in between was an obstacle.

The bus hissed as it came to a stop, some of the men grabbing a handhold for balance, some finding that balance on other shoulders. I could hear the girls outside, greeting the soldiers as they stepped off, the excited shouts from the men, the reunion of warm hearts on cool asphalt, all the happy chatter and squeals that women do when they greet their men.

A hand came over the back of the bench and gripped my shoulder.

“He was a good man. Sorry.”

“Thanks,” I said. I looked back. The man was dark, older than the others.

“I was in his patrol outside of Seoul. He always had the best cigarettes.”

“He didn’t smoke.”

“No, he would give them to us. Hand-rolled smokes. I don’t know where he got ‘em.” He patted my shoulder again. “I was sad to hear it.”

“Thanks.”

They hurried off the bus, the men at the back leaning to wave and shout through the windows as they pushed to the exit. I could feel the suspension bounce as each man stepped off. Then all the noise was outside and I sat alone. I stood and gathered my bag, slung it over my shoulder, and straightened my jacket. The driver sat potbellied behind the wheel, his elbow propped up, watching the men and women in the lot with a satisfied grin on his face. He twisted on the foam pad to face me, bouncing slightly as he moved about.

“Home again, home again,” he said.

“Dancing a jig,” I said. “How many of these drives have you done?”

“Many. Many more than I thought I’d have had to.”

“What do you think of all this?”

He pulled his shoulders up toward his ears. “Truman wants to stop Communism. I am behind him. If I was twenty again I’d be next to you in the line of fire.”

“Be glad you weren’t.”

He reached in his shirt pocket for a pack of gum, pulling one stick from the pack with his teeth. He held it there as one does to light a cigarette and it bounced with his words.

“I wish I was, son. Truly. Young men go to war because they have nothing else to do and they have been conditioned to think about freedom. They have been molded to protect a right that they don’t fully understand yet. They just know it’s important. That is real bravery. Old men understand it, but we can’t soldier as well as young men. We’d be better off throwing the rifle downrange than trying to sight down its barrel. But you had better believe I would be out there with you.”

“Yes sir.”

“I don’t know much about politics or military. I was never that brave. I just drive the bus. They won’t give me a rifle, but they let me have these keys. So that’s my service. I see boys like you come home and it makes me damn proud to be American.”

“I mean this.” I nodded my head to the soldiers and women embracing just outside the bus door. “What do you think of this?”

“This? Oh, I can never see too much of this.” He peeled the stick of gum bare and pushed it past his lips with a thick finger. “Got a girl out there?”

“No.”

His nose whistled in disappointment. When he realized he was frowning he spoke to cover it up. “Welcome home, son.”

“Thanks for the ride, mister.” I shook his hand.

“Thanks for the freedom, soldier.”

I stepped off the bus, prepared to walk quickly through the hugs and smiles without disturbing anyone, trying to avoid the scene, when she nearly knocked me off balance and I saw up close the greeting the other men were getting. I caught my bag at my elbow, and she drew back embarrassed, straightening her skirt. She looked like a close-up movie extra who steals the one scene they’re in, her hair longer than the short bobs the other men were embracing around us, her eyes big and bright.

“I’m so sorry,” she said, almost in a whisper. “I thought you were someone else.”

“That’s okay.” I could not help but to smile. I swept a hand through my hair and rearranged my bags. “I should come home more often.”

“Are you the last one off?” She was looking over me to the bus steps.

The driver wound a crank, the doors closed, and the bus rumbled away, the hot exhaust billowing black from rusty pipes. He honked twice as he circled, his upper body rising and sinking a slow up and down behind the window as if he was floating in a wave pool. The pale, empty body of the bus shifted loose screws and relieved stiff bars with metal yawns, and she watched, her lungs slowly deflating more as it moved away.

“Not here, is he?”

“You looked like him. For a moment I thought you were him.” She was

concerned now, looking around at the circus of greeting, her lips pressed inward and her eyebrows pushed up on her forehead. Her eyes paused on each face around us. Not so bright anymore, but still big and filled with a kindness that had been pent up, waiting to be released on one lucky soldier who didn’t show.

“We all look alike in uniform.”

“No. Not him. I could spot him from a mile away.”

I shrugged. “I guess not, right?”

“Is there another bus on the way?”

“No. We were the only bus en route.”

“There must be one more. I’ve been here all day.”

“Maybe he got bumped.”

“What?” Her head snapped over and she looked at me, her face in a momentary mess.

“I mean bumped to another plane. Maybe later in the week.”

Her features relaxed a little. “He said today.”

“We’re it for today.”

We looked around. The other soldiers were walking away, hand in hand with girls. Some of them were still locked in a hug or dipped in a kiss, their bags scattered at their feet, wives or girlfriends with welcome posters rolled in their hands, children standing by.

“Looks like we’re a mismatch,” I said.

“What about later tonight?”

“For what?”

“For a bus. More soldiers.”

“We were the last one, miss,” I said. “I’m sorry. He was probably bumped to a later flight. It happens sometimes.”

“He said today.” She held her hands in front her, delicate and wringing. “I’ll wait a little longer. I’m terribly sorry about the mistake. You have the same hair as him.”

“Don’t worry about it.” I pulled my bag onto my shoulder and turned to walk. I looked back at her, a lone figure at the line with unreleased welcome still inside her. “You’ll wait all night.”

“It’s all right. I’ve been waiting so long now anyway. I’ll wait.”

A cool, spring breeze tossed her hair sideways and made her squint. She put her hands at her skirt and looked to the gate, raising one hand to take the sun away.

I took a step toward the cafeteria. “Come inside,” I said. “I’ll get you a Coke.”

Inside, I took two Cokes from the refrigerator. In the reflection of the glass, I saw her swipe her hands under her skirt and sit at the table. She had a great posture, but she craned her neck to watch the lot, giving her head a chickenlike stretch on her shoulders. The cafeteria was empty but for a Hispanic boy with a hairnet wiping down the tables. He smiled with big front teeth and gave a deep bow when I paid him for the Cokes.

“It could be that he was held behind for patrol assignments.” I slid the bottle to her and sat across from her. I tapped a straw twice on the table and let her pick it from the wrapper.

“He said he would arrive today in his letter.” She put her lips to the straw and the bottle drained slowly. She held her eyes sideways to watch the window. An innocent pose you might see in a soda advertisement.

“Well, it’s not like a flight from Dallas to Midway International. They pack us like sardines into cargo planes until the space runs out. Lots of guys get bumped.”

“He’s important. An officer, I think.”

“More the reason to bump him,” I said. “Officers stay behind to tie up loose ends. You’ll get a headache if you drink it fast like that.”

She covered her nose with her hand. “I’m sorry. I’m just nervous.”

“Don’t be. I bet all you girls get nervous.”

She squirmed in her seat. She was wearing a thin, wool sweater, colored for the springtime. “Wouldn’t you?”

“I don’t have a soldier to wait for.” It was a joke, but she didn’t laugh. Instead, she looked at me funny. I straightened up and cleared my throat.

“Do you go to school near here?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“St Mary’s College?”

“Yes.”

“Let me guess your studies,” I said, and leaned forward with my elbows crossed on the table. I was enjoying her. She put me in a different place. A place where there was no loss, only gain, and I could see firsthand the excitement of a prolonged reunion. Girls were excited to see the soldiers come home, and I included myself as the object of her anticipation.

“I would say you are in your first year, so if you’ve found a major, you probably won’t stick to it long.”

“I’m finishing my third year,” she said. “I’ll be a senior in the fall.”

“You look younger.”

“Do I?”

I nodded and she leaned forward, taking mock offense to my assumptions, speaking with a smile buried under her expression.

“Do I also look like the type of student who would not stick to her choice of major?”

“No. It’s just that most don’t.”

“And you went to Notre Dame?”

“Yes. I’m not done yet. I shipped out nine months ago. I’ll start again in the fall.”

“You look more like a student than a soldier.”

“Really?”

“I mean that in the best possible way. I like soldiers. But being a student is a good thing too. Don’t you think?”

“What if I told you I did not stick to my first major?”

“You said most don’t.” She paused a moment. “What did you change to?”

“Geology.”

“Why? Do you like rocks?”

“Because when I closed my eyes and pointed, geology was what my finger landed on in the book of majors.”

“You must have been looking at that page to make it open there.”

“How did you know? I must look like the type who likes rocks.”

She bit her lip and I watched as the red halves parted thoughtfully. “Mmm…maybe. What made you change to geology?”

“Boredom. I chose electrical engineering as a freshman.”

She sat up as if bitten. “That’s an exciting degree.”

“I slept in and was late to the first class. When I opened the door, the professor had the lights off in the auditorium, talking about the importance of electricity or something. I couldn’t see where to sit so I backed out of the room and changed majors.”

“You must not have wanted to be an engineer.”

“Nursing?” I pointed at her.

“No.” She glanced out the window again. “Journalism.”

“You don’t look like a journalism student. Where are your glasses?”

She had a small dimple on one side. It was the first time I had seen her smile unearthed completely. She reached into her purse and pulled out dark, catlike librarian glasses.

“How about now?”

“Now you look like a teacher. Kindergarten.”

“Not a professor?”

“I like kindergarten teachers. There’s something very nice about a kindergarten teacher.”

“There’s something that I like about soldiers too.”

“Is it the uniform? Women always like the uniform.”

“It’s the ideals and the importance of the job. Not everybody is brave enough to be a soldier.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“The uniform is just the pretty wrapping.”

“It’s brown.” I pulled at my collar. “The Navy and the Marines have better ones.”

“But it’s well-tailored. It’s amazing how wearing something that fits so neat and proper makes a man stand out.”

“Do I stand out?”

“Not among other soldiers.”

“Thank you again.”

“You know what I mean. We all look alike in our uniforms, ma’am.” She did her best impression of me.

“Terrible. Do I sound like that?”

“I added the ‘ma’am’ part. You speak like a farm boy.”

“Just Midwest. Everyone’s a farmer out here.”

“Are you?”

“No. Are you? A farm girl?”

“Yes.”

&nb

sp; “Really?”

“Does that surprise you?”

“You just seem like an indoor girl.”

“I am now. My hands have no more calluses and my skin is not tanned.”

“Your skin looks nice. I must look like a leather bag to you.”

“Just tan. It suits you. Does it get hotter in Korea?”

“No more than it gets here. Humid though. But we were out in the sun all day. Look at my hands. MacArthur’s calluses, Truman’s swelling. Of course we weren’t exactly milking cows.”

A jeep passed by and she looked out the window, half-rising to get a better look. An enlisted man honked twice and a soldier jumped into the backseat at a run, the military-issued cylinder bag over his shoulder. The jeep bounced away with jerky, sudden changes in direction and a sputtering tailpipe. The lot was emptying of the men and girls.

“What is it about nursing wounded soldiers that girls like?” I asked.

“I wouldn’t know,” she said politely. “I’m a journalist.”

I nodded stupidly. “Do you write for the Fighting Irish Journal?”

“I did. South Bend Tribune now.”

“A professional. You must be good at it.”

“Not so professional. I tried to write for the Chicago Tribune. They wanted someone with more experience. I’ll try again next year.”

“I’ll read your stories. What is your name?”

“Elle,” she said. “Elle Quinn.”

“Sam.”

We shook hands over the table.

She was quiet for a moment. “Is it scary out there?”

“Sometimes.” I remembered then that she had been waiting for someone else. It took some resolve, but I eliminated myself and mentioned him. “It’s not that bad. When did he write?”

“It’s been three weeks.”

“What was his name? Maybe I know him.”

“He said he was bringing a surprise.”

“What was his name?”

“Peter.”

I remember just a week ago, sitting across from him on a pair of cots. I sat up as he came in, his boots giving him away as he approached. He had a step that I had been able to pick out since boyhood.

“I have a surprise for you,” Peter told me.

“What is it? Night patrol?”

“No. When we get back.” He wrinkled his eyes and pushed my head down. “The surprise is when we get back. I can’t wait to introduce you.”