Sword Brother wg-4

David Weber

Sword Brother

( War God - 4 )

David Weber

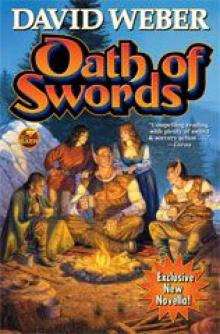

A brand new 50,000 word novella, Sword Brother.From the 20007 year edition of "Oath of Swords"

David Weber

Sword Brother

Foreword

When Toni Weisskopf told me Baen Books was going to reissue Oath of Swords in a trade paperback format, I thought that was a good idea. When she told me she wanted me to write a foreword for it, I thought that was a good idea. When she told me she wanted me to write a foreword for it and give her a new short story set in Bahzell's universe, I thought that was a good idea, too. Of course, that was before I discovered just what my writing schedule was going to look like this year. I still think they're all good ideas, but my life's turned out to be just a bit more . . . interesting, in the Chinese sense of the word, than I anticipated it would.

That happens to me a lot. Ask Sharon, the mother of my children (whom I see from time to time, when I emerge from my writer's garret in search of sustenance).

But that lay in the blissfully unknown future when Toni first proposed this whole idea to me, so I happily added it to my plate, little guessing just how heaping a helping I had loaded there. And, in a spirit of happy creativity, I asked Toni what she'd like to see in a foreword.

"Well," she says to me, "I think you should consider keeping it brief."

"Brief?" says I. "What are you trying to say, Toni?"

"Well," she says, "your last two or three novels have all run to 300,000 words . . . or more."

"And your point is?" says I.

"Never mind, David," she says.

I'm still trying to figure out exactly what she was getting at.

On a more serious note, and a somewhat sadder one, the decision to reissue Oath of Swords was actually made by Jim Baen before his death. I started to say before his "untimely" death, but that, of course, would have been redundant. There really wasn't a time when we could have lost Jim which wouldn't have been "untimely." I miss him, as a professional colleague, as a mentor, as my publisher, and as my friend.

I also take particular, if bittersweet, pleasure, for several reasons, in knowing that it was Jim's idea to reissue this book. First, because it was his idea, and it was the last book of mine that he'll ever schedule. Second, because Jim was suggesting the reissue of a David Weber fantasy novel, when he could have been inserting another science-fiction novel into the schedule. And third, because I've always had a deep respect for Jim's instincts when it came to scheduling and positioning books.

When Toni and I first discussed this, neither of us had any idea that we were going to lose Jim. Because of that, we'd both rather looked foreword to twitting Jim (relatively) gently in the foreword, since he was always in something of two minds where my fantasy novels were concerned. He liked them, and their sales were certainly respectable, but he pointed out-correctly-that I'm rather better known for my military science fiction than as a fantasy author. As such, the sales of Bahzell's books have never been as good as, say, the sales figures for Honor Harrington's books. In other words, as he used to tell me, I was taking a cut in pay, as it were, whenever I sat down to write about Bahzell.

He was right, of course. He tended to be right about things like that with sometimes irritating frequency. And as a publisher-not to say a shameless huckster, which he also was, bless him-he was quite rightly concerned about the bottom line. As a matter of fact, that was one of his jobs as publisher, since some writers (oh, I'm not talking about myself, of course!) experience some difficulty counting above ten with their shoes on. The remarkable thing about it was that even though the sales figures on these books were lower than those on most of my science fiction, Jim still found room on the Baen Books schedule for three of them, with two more still under contract. He knew they were important to me, you see, and that-bottom line or not-made them important to him, as well.

And why were they important to me? I'm glad you asked that. You did ask, didn't you? Well, someone did, I'm sure.

The truth is that I've always loved fantasy. In fact, the first novel I ever wrote (which wasn't bought, shocking as that news may be to some people) was a fantasy. As a matter of fact, Bahzell was in that book, too, and if there were any justice in the world -

But I digress.

One of the reasons I enjoy both reading and writing fantasy is that the fundamental assumptions that go into building a fantasy world or universe are both different from and similar to the ones that go into building a science fiction world or universe. Or they are for me, at least. The parameters aren't looser so much as more . . . flexible.

There are certain ingredients that are necessary to make a literary universe that hangs together, that's both convincing and consistent enough that readers actually want to visit. The "technology,"whether it's science-based or magic-based, has to be consistent. The characters have to have a toolbox with both advantages and limitations the writer agrees to abide by, and they have to solve their problems without his suddenly dropping a brand-new tool into the box because he discovers he's painted himself into a corner. The people who live in it have to be believable, and they have to be characters the reader actually cares about. Readers don't have to like the characters (although it does help if they like at least some of them), but they do have to care about what happens to them. The social matrix has to be internally consistent, well thought out, and believable. Whether or not politics are centerstage in the novels set in a universe, the writer has to understand what the political subtext is and abide by it. And the writer has to remember that if he's writing about an entire world, it's probably at least a little bit bigger than Rhode Island. It might even be bigger than Texas. In either case, it's going to have variations of climate, terrain, people, flora, and fauna.

In a fantasy universe, the "tool box's" rules are less restrictive, but that doesn't absolve the writer of his responsibility to be consistent. The social and political design work still have to be done right, too, and, in some ways, the genre itself has traditionally been rather more limiting. There are expectations, especially in "swords-and-sorcery" fantasy. For example, if you put orcs (or their equivalent) into a fantasy novel, they're probably going to be the bad guys. Elves may be followers of the light or of the dark, but there are certain inherently "elvish" qualities we generally expect to find. Half-elves usually combine the best of both human and elf, and everyone knows the dwarves are greedy, grasping, avaricious sorts who usually end up with the short end of the stick, at least as far as anyone's actually liking or admiring them.

Please note that I said these are expectations. The best fantasy writers, I think, are those who can take those expectations and lead their readers somewhere else without losing them. Those are the ones I've always most enjoyed reading, at least. Mind you, I'm not talking about Tolkien here. Most of the expectations in modern English-language fantasy derive from his work in one way or another, and in my opinion the reason they do is that he did them so very, very well.

At any rate, one of the reasons I wanted to write the Bahzell books was to bend some of those expectations myself. For example, the hradani obviously fill the same "ecological niche" as Tolkien's orcs in some ways, but my hero is a hradani. In fact, we spend more time with his people than with anyone else. The gods are very involved, yet they aren't omniscient and they are ultimately dependent on the actions of mortals to accomplish their ends. The half-elves are the nasty, bigoted racists. The elves spend most of their time dreaming and generally avoiding contact with a world which has bruised and abused them once too often. And the dwarves run Norfressa's one true superpower. (Ha! Take that, silly elvish k-nig-it!) And I might as well go ahead and admit right now that I'm still not through bending.

I'

ve still adopted quite a bit of the mainstream "high fantasy," I suppose. To some extent I think that's inevitable, given the sort of stories I want to tell. But it's the differences, the spaces between the expectations, with which I most enjoy playing.

Fantasy is also a good place to play with concepts of good and evil, of responsibility and morality. It's a place which is actually designed to let us build heroes and villains who are bigger than life. It can be pure escapism, but there's always a mirror hiding somewhere deep down in the depths, waiting for us to look into it, often when we least expect it.

And, finally, from my own perspective as a writer, fantasy offers a welcome break from science fiction. I'm a production writer, and I produce somewhere around two million words a year. That's a lot of time in front of the keyboard (well, wearing the voice-activated headset, in my own case), and switching gears helps refresh the sense of wonder and enjoyment that keeps me writing. As any of you who have read my science fiction are undoubtedly aware, I like writing series. I like big story lines, that don't really lend themselves very well to resolution between a single set of covers. And I like to watch characters, events, and societies evolve and grow over several volumes. But maintaining the energy in a series, keeping up the writer's own interest to a level that makes new books enjoyable for his readers, requires occasional breaks. In many respects, the Bahzell novels have represented breaks for me.

At the same time, they aren't something I write only as a vacation from my "real writing." The very thing that makes them a break for me is the enjoyment I find in working on them and the different constraints and opportunities my fantasy characters face as opposed to my science fiction characters.

If I can ever find the time for it, I have at least seven more novels I want to set in Bahzell's universe. Two of them will deal with Bahzell, Brandark, and their further adventures. The other five will include all the (surviving) major characters from the first five books, but most of those major characters will be appearing in very important yet ultimately supporting roles as I get around to finally resolving the lingering conflict between the Kontovarans and the Norfressans. The problem, obviously, is finding time to sandwich those books in amongst the science fiction novels which, as Jim pointed out to me, actually pay the rent.

Now, I have a theory about that. Jim and I discussed it off and on for years. My argument was that if I had more fantasy titles on the shelves, then fantasy readers might actually decide to look for them and even-gasp!-decide to recommend them to their friends. I might even-who knows?-come to be known as a fantasy writer, as well as a science fiction writer, and then the fantasy novels might start generating enough income to make Jim happy to see them. You see the point I'm cunningly making here? If you buy the books, and if you encourage your friends to buy them, then it'll get easier for me to convince Baen Books to let me write even more of them, which will put more of them on the shelves, which will generate more sales, which will . . . Well, I'm sure you get the point, and I hope at least some of you will think this would be a Good Thing.

I expect Toni will go ahead and let me squeeze them into my writing schedule anyway. She understands how important they are for that gear-switching I mentioned above. Besides, I think she likes them. Of course, she could just be trying to avoid hurting my feelings . . . .

Nah, not Toni!

At any rate, here's Oath of Swords, the first of Bahzell Bahnakson's adventures and misadventures. The new novella included with it isn't set at any particular point in Bahzell's life. Those of you who have read the other novels will realize it comes after certain events in them, but aside from that, its exact chronology sort of floats in the timeline of the mainstream of the series. Who knows, maybe it was all a dream. Then again, Tomanâk did warn him about all those alternate universes-

What? Oh, that was in Wind Rider's Oath, wasn't it? (Shameless plug for later book in series.)

I hope you like it. I hope you tell Toni you like it, so I can write more of them sooner. Eventually, assuming I'm not struck by a meteorite or something equally drastic, I will get them all written, I'm sure. But I'm not going to complain if you choose to bombard Baen Books' offices with requests for more of them in the meantime.

Honest.

David Weber

I

He was thinking about snow when it happened.

He really ought to have been getting his mind totally focused on the task at hand, but the temperature had topped 110° that afternoon, and even now, with the sun well down, it was still in the nineties. That was more than enough to make any man dream about being some place cooler, even if it had been-what? Three years since he'd really seen snow?

No, he corrected himself with a familiar pang of anguish. Two and a half years . . . since that final skiing trip with Gwynn.

Gunnery Sergeant Kenneth Houghton's jaw tightened. After so long the pain should have eased, but it hadn't. Or perhaps it had. Right after he'd received word about the accident, it had been so vast, so terrible, it had threatened to suck him under like some black, freezing tide. Now it was only a wound which would never heal.

The thought ran below the surface of his mind as he stood in the commander's hatch on the right side of the LAV's flat-topped turret and gazed out into the night. As the senior noncom in Lieutenant Alvarez's platoon, Houghton commanded the number two LAV (unofficially known as "Tough Mama" by her crew), with Corporal Jack Mashita as his driver and Corporal Diego Santander as his gunner. Tough Mama was technically an LAV-25, a light armored vehicle based on the Canadian-built MOWAG Piranha, an eight-wheel amphibious vehicle, armored against small arms fire and armed with an M242 25-millimeter Bushmaster chain gun and a coaxial M240 7.62-millimeter machine gun. A second M240 was pintle-mounted at the commander's station, and Tough Mama was capable of speeds of over sixty miles per hour on decent roads. She drank JP-8 diesel fuel, and technically, had an operational range of over four hundred miles in four-wheel drive. In eight-wheel drive, range fell rapidly, and the original LAVs had been infamous for leaky fuel tanks which had reduced nominal range even further. The most recent service life extension program seemed to have finally gotten on top of that problem, at least.

At the moment, Mashita was sitting behind the wheel, with the big Detroit diesel engine to his immediate right and his head and shoulders sticking up through the hatch above his compartment. The twenty-year old corporal had just finished checking all of the fluid levels-which he'd do again, every time the vehicle stopped. Santander was standing to one side, jaw methodically working on a huge wad of gum, as he spoke quietly with Corporal Levi Johnson, the senior of their evening's passengers. The four-man recon section they were responsible for transporting and supporting had already stowed most of its gear aboard, and Houghton reminded himself to check the tunnel from the LAV's driver's compartment to the troop compartment before they actually headed out. It was supposed to be kept clear at all times, but people had a habit of protecting equipment and gear from damage by stowing it in the tunnel, rather than stowing it in the open-sided bin mounted on the back of the turret or lashing it to the outside of the vehicle, the way they were supposed to.

Houghton had already completed all of his other pre-mission checks. Fuel, battery, ammo, night-vision, thermal sights, commo, personal weapons . . . He still had a good twenty minutes before they were scheduled to leave, but he and his crew were firm believers in staying well ahead of deadlines.

Never hurts to be ready sooner than you have to, he reflected, the back of his mind still visualizing the silent, steady sweep of snowflakes. It sure as hell beats the alternative, anyway!And the LT won't like it if something screws up while-

That was when it happened.

The universe went abruptly, shockinglygray. Not black, not foggy, not hazy-gray. His brain insisted that the featureless grayness which had enveloped him was almost painfully bright, but his pupils and optic nerve were equally insistent that the light level hadn't changed at all. His hands death-locked on the rim of the commander

's hatch as the fourteen-ton LAV seemed to fall out from under him, yet even as that sickening sense of freefall swept over him, he knew he hadn't actually moved at all.

After sixteen years in the Corps, Ken Houghton figured he'd seen and experienced just about anything that was likely to come a Marine's way. This was something else entirely, though-something human senses had never been intended to grasp or describe-and a burst of something far too much like panic blazed through him.

It seemed to go on for hours, but there also seemed to be something wrong with his time sense. He couldn't seem to speak, didn't even seem to be breathing, yet he managed to look down at his wristwatch, and the digital display was crawling, crawling. He could have counted to ten-slowly-in the time it took each broken-backed second to drag itself into eternity. Two agonizingly slow minutes limped past. Then three. Five. Ten. And then, as suddenly as the universe's colors had disappeared, they were back.

But they were the wrong colors.

The tans and grays and sun-blasted browns of the Middle East were gone. And so was the night. The LAV sat on a gently sloping hillside covered in prairie grasses three or four feet tall under a sun that was still at least two or three hours short of setting.

Houghton heard Mashita's deep, explosive grunt of astonishment over the helmet commo link, but the gunnery sergeant hadn't needed that to tell him they weren't in Kansas anymore.

Houghton stared in stupefied disbelief at the high, crystalline blue sky, felt the autumnal chill in the slight breeze cooling the sweat on his desert-bronzed face, heard the birds that shouldn't have been there, and wondered what the hell had happened. He turned his head slowly, and that was when he saw the tall, white-haired man with the peculiar eyes standing almost directly behind the LAV.