Barefoot to Avalon

David Payne

BAREFOOT TO AVALON

ALSO BY DAVID PAYNE

Confessions of a Taoist on Wall Street

Early from the Dance

Ruin Creek

Gravesend Light

Back to Wando Passo

David Payne

Barefoot to Avalon

A Brother’s Story

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright © 2015 by David Payne

Jacket design by Elixir Design

Author photograph by Mathieu Bourgois

Page ix: Excerpt from Roth, Philip, The Counterlife. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986. Page 21: Excerpt from “It All Comes Together outside the Restroom in Hogansville” by James Seay taken from Seay, James, Water Tables. © 1974 by Wesleyan University Press. Used with permission. Page 24: Excerpt from “Burnt Norton” by T. S. Eliot taken from Eliot, T. S., Collected Poems 1909–1935. London: Faber, 1936, by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company; Copyright © renewed 1964 by T.S. Eliot. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Page 43: Excerpt from Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner copyright © 1936 by William Faulkner and renewed 1964 by Estelle Faulkner and Jill Faulkner Summers. Used by permission of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Page 65: “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T. S. Eliot was first published in Poetry magazine in 1915. All lines quoted are public domain. Page 70: excerpt from One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish by Dr. Seuss, ® and copyright © by Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P., 1960, renewed 1988. Used by permission of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Pages 78, 124, 138: Excerpts taken from Jung, C. G., Memories, Dreams and Reflections. New York: Pantheon Books, 1963.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or [email protected].

Note from the author: Though this book is a memoir, I’ve changed the names, residences and certain background details to preserve the privacy of characters who aren’t members of my immediate family.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8021-2354-1

eISBN 978-0-8021-9184-7

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

Contents

Prologue

Part I

2000

Part II

2006

Part III

1975

The Bridge

Part IV

2000

Part V

2006

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

To George A.

“In a way brothers probably know each other better than they ever know anyone else.”

“How they know each other, in my experience, is as a kind of deformation of themselves.”

—The Counterlife, Philip Roth

Prologue

In my earliest memory I’m three years old, running down the hall of our old house in Henderson, North Carolina, a small, gray-shingled one in a stand of oak trees on a hilltop overlooking Ruin Creek. I’m wearing my special cowboy outfit, black hat and vest with tinselly Charro trim. My mother has just come out of the bathroom, and we collide. Margaret, twenty-two, seems ageless, a film goddess from a prior era caught in close-up on the big screen at the drive-in. Her black hair is down and she wears a loose robe. As she sashes it, I note her swollen belly.

–You’re fat! I cry gleefully, as though I’ve caught her at some trespass the way she frequently does me.

Margaret smiles as though about to share a wonderful surprise.

–You’re going to have a new little brother or sister, she tells me.

I stand there, smiling vacantly. In my head, a static noise like the TV after midnight station sign-off, when the Indian Head test pattern appears after the singing of the anthem.

I take my silver six-gun, place it against her stomach and pull the trigger.

–Bang! I say and run off laughing.

I

2000

And the Lord said unto him . . . What hast thou done? The voice of thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground.

—Genesis 4:10

1

On November 7, 2000, at around 8:30 in the evening, as the polls are closing in the East and the networks give the early edge to Gore, I lock the door of our house in Wells, Vermont, and place the key, by prearrangement with the realtor, in a Tupperware container under the back steps. In the dark front yard, a twenty-six-foot U-Haul truck sits low on its suspension, its lights angled toward the culvert at the top of our steep gravel drive. The high beams splash a stand of birches and lose themselves in the thick woods on Northeast Mountain, which looms over the protected meadow I bought eleven years ago and where I built the house I’m leaving.

My 1996 Ford Explorer idles nearby, and I can see George A., my brother—forty-two and heavy, his thick black hair and mustache sable-frosted—smoking in the greenish backwash from the panel. On the hitch is the twelve-foot trailer I didn’t think we’d need when he flew up last week to help. Stacy, my wife, is already in North Carolina with our two-year-old daughter and our infant son. Having the children underfoot, we’ve agreed, would make a stressful job more difficult.

For eight days, George A.’s gone with me room by room and shelf by shelf, taking the Wells house apart, down to the wild turkey feathers and New York City restaurant matchbooks, the loose change scattered at the bottoms of the drawers.

My original plan had us leaving after lunch on Sunday, two days ago, November 5. By midnight Sunday night we’d just started to attack the bookcase in the great room I drew and built with nine-foot sidewalls and a vaulted ceiling and a loft and barn sash windows in the gables. On a ladder, pulling volumes down, I handed George A. the family pictures and fragile ware, and he—crossed-legged on the plank pine floor in soiled white socks—swaddled them in Bubble Wrap, tearing ragged swaths of masking tape and fighting with the roll. It seemed to me the tremor in his hands had worsened and the smudges beneath his eyes were darker—like the eye grease he wore when he played ball beneath the lights on Friday nights in high school. The difference was worrisome.

It had been eight months, perhaps a year, since I’d seen him. The last time I visited Winston-Salem, I caught the smell of George A.’s cigarettes as soon as I walked in the front door of Margaret’s town house, where I found her alone in a pool of lamplight in the small front parlor, working on a book and a glass of Pinot. She—who’d stopped smoking years before—looked up at me with a grievance in black eyes that were George A.’s eyes, too—something bemused and sad and angry and exhausted, resolved above all e

lse to see it through—while George A. chain-smoked in the larger den in back and sipped a beer and laughed his croupy laugh at South Park. Once a top producer in the Winston office of Dean Witter Reynolds, married with two sons in private school, a BMW and a house in the tony district, Buena Vista, George A. had been there with Margaret for nine years. The tension was so thick a knife would not have scratched it. During the day when Margaret was at work, he smoked and watched the back crawl of the ticker tape on the financial channel. At night when she came home, Margaret cooked his supper and took it to him on a tray, and when he’d eaten, George A. left it for her on the kitchen counter and she’d tiptoe up and kiss his cheek and tuck a $10 or $20 in his pocket as he headed to the bar—no longer the one favored by the hotshot brokers with their Gordon Gecko haircuts and spiffy braces—but to Rita’s, a humbler establishment in Clemmons, an exurb twelve miles distant, where Margaret had lived with Jack Furst, her second husband, after they were married.

I knew why our mother did this, why she cooked his meals and paid his medical and life insurance premiums, why she’d bought him the new Chevy Blazer and took his guns and hid them at a friend’s house, including the double-barreled A. H. Fox our grandfather had left me that was reassigned to George A. in the aftermath of his first breakdown. George A. had been diagnosed with manic depression, or bipolar I disorder.

The DSM, the manual of the American Psychiatric Association, categorizes bipolar I by degree, as mild, moderate or severe. George A.’s was “severe, with psychotic features.” Since the age of seventeen, he’d experienced periodic breakdowns—manic highs followed by protracted, crippling depressions—at three- or four-year intervals. During manic phases, George A. experienced the incandescent highs that tempt so many sufferers to go off their meds, pour out their secrets to bewildered strangers on the street, risk their savings on a hand of cards, embark on dubious business ventures and occasionally to triumph. The list of brilliant sufferers is long and includes many artists—Byron, Hemingway, van Gogh, Virginia Woolf, Graham Greene and scores of others. In George A.’s case, over weeks and months, the mania accelerated toward psychosis, when he experienced hallucinations and delusions, believed he’d been assigned “missions” by supernatural agents. Then, he’d wind up in the psych ward.

People with bipolar disorder commit suicide at a rate fifteen times that of the general population, and we know George A. had attempted it at least once. His episodes lasted a few months, three or four on average, and between them, for years at a time, he was seemingly normal and high-functioning. A gifted and successful broker, well liked and relied on by his clients, he was promoted many times at his office. From his first breakdown in 1975, until 1991, he gathered himself after each episode and went back to his life, career and family. Sixteen years after that first one, however, in a manic phase, he made unauthorized trades at work, was sued and lost his job and his wife divorced him. After the hospital that time, George A. went home to Margaret’s to recover and never left. According to the DSM, “Many individuals with bipolar disorder return to a fully functional level between episodes.” George A. had been one of them. Now he’d become part of a different group, the 30 percent who suffer “severe impairment in work role function.”

Living far away, I’d failed to see the deterioration as it happened and didn’t really understand it. He’d risen from the ashes so many times—why not this time? His intelligence appeared unimpaired. When he could scrape the cash together, he still made short sales, traded options and executed complex financial gambits. It seemed to me that there was too much left of George A., too much of Margaret, for them to fall into the enchantment that held them in the black woods they were lost in. As the years went by I visited North Carolina less frequently and spoke to him less often. Sometimes when I called, Margaret put him on and we spoke for a minute about the season prospects for the Tar Heels or cracked wise about Bill Payne, our long-vanished father.

Those tremors, though, those smudges had something more serious in them than I’d grasped. Against it, my certainties and resentments seemed suddenly small and brittle.

Once upon a time in that gray-shingled house on Ruin Creek in the little amber room we shared, George A. slept beneath me in the bottom bunk and we had matching cowboy quilts and college pennants thumbtacked to the wall. On summer nights we kept the windows open and could hear the creek below us in the creekbed. My oldest competitor and ally, he was the only one who knew or ever would know what that time and place had been for me, as I was the only one who knew for George A.—our much younger brother, Bennett, grew up after I left home, in Margaret’s second marriage, in a different house, a different town, a different family under Margaret’s second husband Jack’s regime. Preoccupied with my affairs and far away, I’d failed to see what had happened to George A. and had let things shutter down till there was almost no light left between us.

Then the lightning struck me. After working four years on a novel under contract, I sent in the final pages and the editor rejected it. Instead of the installment payment I expected on completion, suddenly I owed back four years’ worth of income. In the two years it took me to resolve this, Stacy and I lived on credit card advances and I burned out my thyroid gland and cracked four bottom molars, grinding them while sleeping. By the end, I could barely bring myself to walk down to the mailbox, afraid to find the letter commencing legal action. My single-jigger vodka had become a double and I was often having double doubles and, on bad days, triple doubles, and Stacy and I were either fighting about money or practicing mutual avoidance, and in Vermont it was as if we were under an enchantment like George A. and Margaret’s down in Winston, and maybe that was why I could no longer call my brother.

Then Stacy, pregnant for the second time in two years, took our toddler and told me she was leaving, moving back to North Carolina with me or without me, and that if I wanted to be married to her and to be a father to our child—our children—that’s where I could find her, and then she walked off down the jetway in Albany carrying Grace, our towheaded little daughter, who looked back at me over her mother’s shoulder. And as I drove home to Wells and set out into the meadow with my chain saw, I knew I was saying goodbye to the place and bringing in my firewood for the last time.

I called the realtor. I called Mayflower. The quote they gave me for the men with the big van was about as feasible by then as a summer on the Riviera. I called Margaret and told her I was moving back to try to save my marriage and that I meant to rent a truck and pack it.

–Why don’t you ask George A. to help you? she asked.

–Let me sleep on that, I answered.

I didn’t get to. Less than an hour after we hung up, the phone rang and it was George A., offering his help.

And here he was—by then we’d been at it since 8 A.M.—wrestling the masking tape with his unsteady hands at midnight Sunday, November 5.

And though on the first day, when I picked him up in Albany, we were careful and subdued in the beginning, by evening we were cracking jokes and playing music. I played him OK Computer, and he played me Tupac’s “I Ain’t Mad at Cha” and “Picture Me Rollin’.” We picked it up where we’d dropped it somewhere long before, as if no time had passed at all. In the middle of a bad thing, I got back my brother.

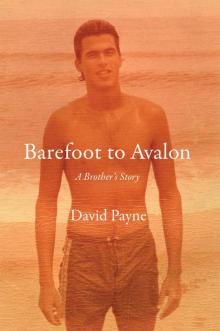

–Check this one out, I said, handing him a faded 4x6 in a cheap Plexiglas frame. It was him, bare-chested, wearing Birdwell boardshorts, on the beach at Four Roses, our family summer house, a week or two before his seventeenth birthday.

–Was this the day I beat you to the pier?

–The one time, I said.

George A. stared at it like a pilgrim at a relic.

–I was pretty good-looking, wasn’t I?

–Was, I said. Not that you’re that bad now—just not, you know, good.

–I guess we’ve all seen better days, he answered, glancing at my ball cap, the one I’d taken to wearing as my hair thinned, while his

stayed thicker than a mink’s pelt.

–Touché, dickwad.

–Heh heh heh, said George A., and his old laugh had something new in it, a hint of broken crockery or gravel. I did kick your ass pretty bad, though, didn’t I?

–You beat me by a small, small margin, bro. Inches.

I held a thumb and index finger up.

–I think you’re measuring something else, he said.

I widened my eyes.

–Ass-hole!

And George A.—who was as prone to laugh at his own jokes as I am—rolled over on his side and slapped the floor, convulsing.

–Jesus. Jesus, he said, tapering off. I’ve got to go to bed, DP. I’m going to catch a smoke and hit it.

–Go on and fire it up in here, I told him as he started rising. Doesn’t make much difference now.

All week he’d been going out to the front porch, using a Hellmann’s mayo jar lid for an ashtray and tucking it into the mulch in the front bed as though to hide the evidence.

–Nah, that’s okay, he said, and so I joined him outside in the Indian summer weather. The meadows had just been mowed and the air was fragrant with green hay scent with an undertone of something inorganic, perhaps diesel from my neighbor’s tractor.

–You can really see the stars up here, George A. said, blowing his smoke toward them.

–The summer I was building, I used to drive up the Taconic from the city on Friday nights, and I’d camp here and build a fire when the stud walls were going up. The night the house was finished—it was right around this time, but cold—I got here after midnight and the northern lights were playing. Right up there—I pointed over Northeast Mountain. Pulsing waves. Green, like an oscilloscope. That was the only time I ever saw them. I’m going to miss this place.

–I think you’re doing the right thing.