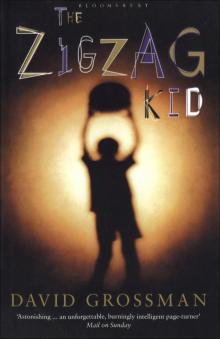

The Zigzag Kid

David Grossman

To my children, Yonatan, Uri, and Ruti

Contents

1

2

3 Tenderhearted Elephants

4 My Debut in a Monocle

5 Walt, Is He a Good Guy or a Bad Guy?

6 What’s Come Over Me?

7 Some Personal Reflections on Driving Locomotives; and the Difficulty of Breaking the Habit Thereof

8 Mischief In the Toy Department

9 We Fugitives from Justice

10 A Chapter I Prefer to Leave Without a Title, Particularly a Humorous One

11 Stop In the Name of the Law!

12 I Uncover His Identity: The Golden Ear of Wheat and the Purple Scarf

13 Are Feelings Touchable?

14 Wanted: Dulcinea

15 The Bullfight

16 A Brief Moment of Light in the Dark before Dark

17 The Infinite Distance Between Her Body and His

18 Like a Creature of the Night

19 Riders of the Sands

20 Do You Believe in Reincarnation? and Also, I Make the Headlines

21 Quick on the Draw: A Question of Love

22 The Bird in Winter

23 Just Like the Cinema

24 The Detective’s Son

25 Zohara Sets Forth to Cross the Moon, and Cupid Resorts to Firearms

26 No Two People Have Ever Been So Incompatible

27 The Empty House

28 This is Too Much

29 Will Wonders Never Cease

Footnotes

About the Author

By the Same Author

Also Available by David Grossman

1

The whistle blew and the train pulled out of the station. There was a boy at one of the compartment windows watching a man and a woman wave to him from the platform. The man waved one hand in a shy little farewell. The woman waved both hands plus a large red scarf. The man was his father, and the woman was Gabriella, a.k.a. Gabi. The man was wearing a police uniform because he was a policeman. The woman wore a black dress because black is slimming. Vertical stripes are also slimming, but if you really want to look slim, she used to joke, stand close to someone even fatter than you, though I have yet to meet anyone quite that fat.

The boy at the window of the moving train, gazing back as though he might never see this picture again, was me. Now they’ll be alone together for two whole days, I thought. All is lost.

The mere thought was enough to yank me out the window by the roots of my hair. I could see Dad’s mouth forming the grimace Gabi called his “final warning before legal action.” Well, too bad. If he cared so much, why did he send me to Haifa for two days, to stay with “him”!

A uniformed trainman on the platform blew his whistle loudly and motioned me to put my head back in. It’s a crazy thing, the way men in uniforms with whistles will always pick on me, out of a whole train-load of people. But I would not obey. I stuck my head out even farther, in fact, so that Dad and Gabi would see me till the last possible second and remember the kid!

The train was rolling slowly off through waves of heat and diesel fumes. There was something new in the air, the smell of travel, the smell of freedom. Here I was, taking a trip! All by myself! I presented first one cheek and then the other to the warm caress of the breeze. I wanted to dry off Dad’s kiss. He’d never kissed me like that before in public. So why did he do it this time and then send me away?

Now there were three uniformed trainmen on the platform blowing whistles at me. A regular orchestra. Since I couldn’t see Dad and Gabi anymore, I pulled myself back in, slow and casual like, to show I didn’t give a hoot about their whistles.

I sat down. Too bad there was no one sharing the compartment with me. Now what? It was a four-hour ride from Jerusalem to Haifa, at the end of which I would be met by the grim-faced Dr. Samuel Shilhav, distinguished educator, author of seven textbooks, and, as it happens, my uncle, the elder brother of my dad.

I stood up. Checked twice to see how the window opened and closed. Opened and closed the trash receptacle, too. There was nothing left to open and close. Everything worked. Pretty cool train.

Then I climbed up on the seat, wriggled my way into the luggage rack, and let myself down again, headfirst, to check whether a certain someone had lost any change under the seats. But he hadn’t. He was obviously a someone you could count on.

Darn them! Dad and Gabi! Why did they have to turn me over to Uncle Samuel a week before my bar mitzvah? Okay, Dad was Dad, he practically worshipped his brother, the great educator and all that, but Gabi, who called him “the Owl” behind his back? Was this the special gift she’d promised me?

There was a little hole in the upholstery. I poked my finger inside and made it bigger. Sometimes you find coins in such places. But all I found in there was foam rubber and springs. I had four hours to tunnel my way through at least three cars to freedom. I would disappear and never have to face grouchy Uncle Samuel Shilhav (formerly Feuerberg). Just let them dare send me away again.

I ran out of finger long before I got through the three cars. I lay on the seat with my feet in the air. I was a captive here, a prisoner in transit, on his way to meet the judge. Loose change fell out of my pocket. Coins rolled through the compartment. Some of them I found, some I didn’t.

Every child in our extended family was expected to submit to one of these sessions with Uncle Shilhav, a form of torture Gabi calls “Shilhavization.” Only for me, this was the second time. No one had ever gone through it twice and come away sane. I jumped up on the seat and started drumming on the wall. Then I changed to a rhythmic tapping. Maybe there was another poor prisoner in the next compartment eager to communicate with a fellow fool of fortune. Maybe the train was full of juvenile delinquents on their way to my Uncle Shilhav. I banged the wall again, this time with my foot. The conductor walked in and yelled at me to sit still. I did.

My previous Shilhavization had been enough for a lifetime. I was put through it after getting into that trouble over Pessia Mautner, the cow. Uncle Samuel shut the door of his stuffy little office and devoted two hours of his time to me. He began in a restrained whisper, and even remembered my name at first, but soon he forgot where he was and with whom, and was probably imagining himself on a podium, addressing a crowd of former students and admirers.

But why now—again? What did I do? I was innocent. “It’s important for you to hear what Uncle Samuel has to say before your bar mitzvah,” said Gabi. Suddenly he was “Uncle Samuel”?

But I knew.

She wanted me out of the way so she could split with Dad.

I stood up. I joggled to and fro. I sat down again. I should never have left them alone together. I knew exactly what would happen. They would fight and say horrible things to each other without me around and I would never be able to get them back together. My fate was being decided there.

“Why don’t we talk about it later, at work?” Dad was saying now.

“Because there are always people coming in and out of your office, and phone calls and interruptions. It’s impossible to have a discussion there. Let’s go sit at a café.”

“A café?” asks Dad, astonished. “You mean right now—in the middle of the day? Is it that serious?”

“Don’t make light of everything.” Now she’s annoyed with him. The tip of her nose has turned red, the way it does whenever she’s about to start crying.

“If it’s the subject we were discussing earlier,” says Dad gruffly, “forget it. Nothing’s changed since our last talk. I’m just not ready yet.”

“Well, this time you’re going to listen to what I have to say,” says Gabi. “The least you can do is hear me out!”

They get into the police car then, and Dad turns the key in the ignitio

n. His shoulder insignia flicker ominously. His face is stern. Gabi shrinks into her seat. Not a word has been spoken, but the fight has begun. Gabi takes a little round mirror out of her purse. She glances at her reflection, tries to smooth down her frizzy hair. “Monkey-face,” she broods.

“Stop it!” I leaped up in the moving train. I forbid Gabi to put herself down like that. I always say, “I think you have a very interesting face.” And seeing that she was not convinced, I would add, “The thing is, you have inner beauty.”

“Yeah, sure,” she would answer. “So how come there are no inner-beauty contests?”

And suddenly I found myself standing by the little red lever next to the window. This was definitely not a good place for me to be, in my present state of mind. Such a lever could stop a train in its tracks, if you happened to pull it accidentally. I read the sign: In case of emergency only. Persons stopping this train for insufficient reason will be subject to a large fine and possible imprisonment. My fingers began to itch, at the tips, and in between. Again I read the warning, in a loud, clear voice. No use. My palms were sweating. I put my hands back in my pockets, but wouldn’t you know, they popped out again. Someone looking on might have thought, Ho hum, just a pair of innocent hands out for a little air. Now I was really sweating. I touched the chain around my neck and the bullet hanging from it, heavy, cool, and soothing. This bullet was taken out of your father’s shoulder, I murmured to myself, and it will always keep you safe from harm. But now I was starting to feel prickly all over.

The old familiar feeling. I knew what would happen next. I’d start rationalizing. The engineer will never guess which of the levers was pulled. But supposing he has some sort of gadget that tells him which one it was? Okay, so as soon as I pull this one I’ll run to the next car. But what if they find my fingerprints on the lever? Maybe I’d better wrap a handkerchief around my hand before I touch it.

Why do I get myself into these arguments I always end up losing? I pumped up my back muscles and stood like Dad, sturdy as a bear, telling myself, Relax, relax, but it didn’t work. There was this hot place between my eyes which on occasions like this tended to get even hotter: it was happening now, overwhelming me, and at the last minute I bent over, grabbed my legs, and forced myself down on the seat. Gabi used to call this trick of mine “protective custody.” She had her own special terminology for everything.

“Look, I’m no spring chicken anymore,” she was saying to Dad at the café. “For twelve years I’ve been practically living with you and Nonny.” So far, so good; she’s under control, speaking quietly, coolly. “For twelve years now I have brought him up and looked after the two of you and your house. I know you like no one else ever will and I want to move in full-time, I want to be more than your secretary and your cook and laundress. And I want to be there as Nonny’s mother all night long, too. What are you so afraid of, would you mind telling me?”

“I’m just not ready,” says Dad, pressing the coffee cup between his big, strong hands.

Gabi pauses for a moment, takes a deep breath, and says, “Well, I can’t go on this way.”

“Look—uh—Gabi,” says Dad, his eyes darting impatiently over her shoulder, “what’s wrong with things as they are? We’re comfortable this way, it works for the three of us. Why change our life all of a sudden?”

“Because I’m forty years old, Jacob, that’s why! I want fulfillment, I want to have a family.” At this point her voice starts to crack. “And I want us to have a child of our own, I want to see the baby you and I would make together. If we wait another year, I may be too old. And Nonny deserves a live-in mother!”

I could recite this speech of hers by heart. She had rehearsed it with me often enough. I was the one who contributed the touching phrase “Nonny deserves a live-in mother.” I also gave her a piece of practical advice: Whatever you do, for God’s sake, don’t cry in front of him! Because the minute she started bawling, it would be all over. If there’s one thing Dad can’t stand, it’s tears, hers or anyone else’s.

“The timing is wrong, Gabi.” He sighs and sneaks a glance at his watch. “Be patient. I can’t decide a thing like this under pressure.”

“I have waited patiently for twelve years. I’m not going to wait anymore.” Silence. He doesn’t answer. Her eyes are brimming over. Oh, please control yourself, Gabi, you hear?

“Jacob, answer me to my face: is it yes or no?”

Silence. Her double chin is trembling. Her lips twitch. If she starts crying now, she’s doomed. And so am I.

“Because if the answer is no, I will get up and leave you, Jacob. This time for good. I mean it!” And she pounds the table with her fist as the tears flow down her puffy face. Mascara trickles over her freckles and collects in the creases around her mouth. Dad frowns in the direction of the window. He can’t bear to see her cry, or maybe it’s the sight of her swollen eyes and her quivering cheeks that he can’t bear.

No, she is not pretty at this moment. And it’s so cruel, too, because if she were the least bit attractive, if she had a sweet little mouth, for instance, or a turned-up nose, he might suddenly have fallen in love with her one good feature. The tiniest beauty mark is sometimes enough to win a man’s heart, even if the woman in question is no queen of outward beauty. But Gabi has no beauty mark, I’m sorry to say.

“Okay, I understand.” She groans through the red scarf, which has recently served a loftier purpose. “What a fool I’ve been to think you could change.”

“Shhh …” he begs her, glancing around. I definitely hope everybody in the café is staring at him now. That all the cooks and waiters come hurrying out of the kitchen and stand around with their arms folded over their aprons, glaring at him. If there’s one thing that scares my dad, it’s a scene. “Look—uh—Gabi,” he tries to soothe her. Actually he seems more gentle now, either because of all the people around or because he senses that she’s serious this time. “Please, give me a little more time to think about it, okay?”

“Why? So that when I’m fifty you can ask me to give you more time again? And what if you decide to tell me it’s over when I’m fifty? Who’ll look at me then? I want to be a mother, Jacob!” People are staring now and he wishes he were dead, but Gabi continues: “I have so much love in me to give a child, and to give to you, too! Haven’t I done well so far as Nonny’s mother? Won’t you try to understand my side of it, too?”

Even during our rehearsals, she would get carried away sometimes and start crying and pleading, as if I were Dad. Then she’d get hold of herself and tell me, red-faced, that certain things were inappropriate for children my age to hear, although it didn’t matter much, really, since I already knew everything anyway.

I did not know everything, though I was learning a lot.

Gabi rolls up the soggy paper napkins and wads them into the ashtray. She wipes away the last traces of mascara from her swollen eyes.

“Today is Sunday,” she says, struggling to keep her voice firm. “The bar mitzvah is next Saturday. You have until next Sunday morning, a full week, to decide.”

“Are you giving me an ultimatum? This isn’t something you can settle with threats, Gabi! I thought you were smarter than that.” His voice is quiet, but the furrow of rage between his eyes grows ominously deeper.

“I don’t have any strength left, Jacob. For twelve years I’ve been smart, and look at me, I’m still alone. Maybe being stupid works better.”

Dad says nothing. His red face is redder than ever.

“Come on, let’s drive back to work,” she says hoarsely. “And by the way, if I’ve guessed your answer correctly, you’d better start looking for a new secretary, too. I’m going to break off all contact with you. Oh yes.”

“Look—uh—Gabi …” says Dad again. He can’t think of anything else to say. “Look—uh—Gabi.”

“Until next Sunday, then.” Gabi cuts him off, stands up, and walks out of the café.

She’s leaving us.

She’s leaving m

e.

In the train my arms and legs break out of “protective custody.” Emergency, emergency, the painted words scream out at me from the red sign above the little lever. The train is carrying me farther and farther away from where my life is just about to be destroyed. I cover my ears and shout, “Amnon Feuerberg! Amnon Feuerberg!” as though someone else were warning me not to touch the lever, trying to save me from myself, someone like a father, or a teacher, or a distinguished educator, or maybe even the head of a reformatory. “Amnon Feuerberg! Amnon Feuerberg!” But nothing will help me now. I’m all alone. Abandoned. I should never have left home. I must return at once. And I stagger toward the lever and reach out. My fingers stretch toward it, because this truly is an emergency.

But just as I am about to pull with all my might, the compartment door opens and in walk two men, a policeman and a prisoner, and both of them stand there, staring in astonishment.

2

I mean—a real policeman and a real prisoner.

The policeman was a wiry guy with a nervous look in his eyes. The prisoner was bigger, burlier. He smiled at me brightly and said, “Mornin’, kid! Off to visit your grandma?”

I wasn’t sure it was legal to answer him. Anyway, why grandma? Did I look like the kind of kid who would visit his grandma, like Little Red Riding-Hood or something?

“No talking to the prisoner!” barked the policeman, severing the invisible strings between us with his skinny hand.

I sat down. I didn’t know what to do. I tried not to look, but naturally, the harder I tried, the more I wanted to. They had an anxious air. Something was wrong. The policeman kept checking their tickets all the time and scratching his head. The prisoner checked the tickets and scratched his head, too. They looked as if they were playing charades, acting out the expression “to rack your brains.”

“Why did you have to go and buy separate seats?” grumbled the prisoner, and the policeman shrugged his shoulders. The man at the ticket counter, he explained, didn’t say that the tickets were for separate seats. He, the policeman, had assumed they would have adjacent seats, because no one in his right mind would sell separate seats to a pair like them, and as he said the words “a pair like us,” he raised his right hand, which was cuffed to the prisoner’s left.