More Than I Love My Life

David Grossman

Also by David Grossman

Fiction

A Horse Walks into a Bar

Falling Out of Time

To the End of the Land

Her Body Knows

Someone to Run With

Be My Knife

The Zigzag Kid

The Book of Intimate Grammar

See Under: Love

The Smile of the Lamb

Nonfiction

Writing in the Dark: Essays on Literature and Politics

Death as a Way of Life: Israel Ten Years After Oslo

Sleeping on a Wire: Conversations with Palestinians in Israel

The Yellow Wind

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Translation copyright © 2021 by Jessica Cohen

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in Israel as Iti ha’chayim mesachek harbeh by Ha’kibbutz Ha’meuchad, Tel Aviv, in 2019. Copyright © 2019 by David Grossman and Ha’kibbutz Ha’meuchad.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Grossman, David, author. | Cohen, Jessica (Translator), translator.

Title: More than I love my life : a novel / David Grossman ; translated by

Jessica Cohen.

Other titles: Iti ha’chayim mesachek harbeh. English

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. | “This is a Borzoi Book”

Identifiers: LCCN 2020035075 (print) | LCCN 2020035076 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593318911 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593318928 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524712044 (open market)

Subjects: LCSH: Goli otok (Concentration camp)—Fiction. | Concentration camp inmates—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PJ5054.G728 I8513 2021 (print) | LCC PJ5054.G728

(ebook) | DDC 892.48/602—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020035075

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020035076

Ebook ISBN 9780593318928

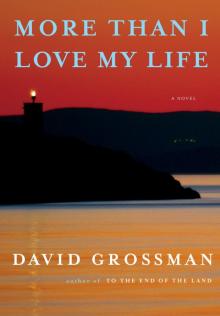

Cover photograph by Daniel Loretto / Panther Media GmbH / Alamy

Cover design by Chip Kidd

ep_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Also by David Grossman

Title Page

Copyright

More Than I Love My Life

Acknowledgments

A Note About the Author and A Note About the Translator

Rafael was fifteen years old when his mother died and put him out of her misery. Rain poured down on the mourners huddled under umbrellas in the small kibbutz cemetery. Tuvia, Rafael’s father, sobbed bitterly. He had cared for his wife devotedly for years and now looked lost and bereft. Rafael, wearing shorts, stood apart from the others and pulled the hood of his sweatshirt over his eyes so that no one would know he wasn’t crying. He thought: Now that she’s dead, she can see all the things I thought of her.

That was in the winter of 1962. A year later his father met Vera Novak, who had come to Israel from Yugoslavia, and they became a couple. Vera had arrived with her only daughter, Nina, a tall, fair-haired girl of seventeen whose long face, which was pale and very beautiful, showed almost no expression.

The boys in Rafael’s class called Nina “Sphinx.” They would sneak behind her and mimic her gait, the way she hugged her body and stared ahead vacantly. When she once caught two kids imitating her, she simply pummeled them bloody. They’d never seen such fighting on the kibbutz. It was hard to believe how much ferocious strength she had in her thin arms and legs. Rumors started flying. They said that while her mother was a political prisoner in the Gulag, little Nina had lived on the streets. The streets, they said, with a meaningful look. They said that in Belgrade she’d joined a gang of feral kids who kidnapped children for ransom. That’s what they said. People say things.

The fight, as well as other incidents and rumors, failed to pierce the fog in which Rafael lived after his mother’s death. For months he was in a self-induced coma. Twice a day, morning and evening, he took a powerful sleeping pill from his mother’s medicine cabinet. He didn’t even notice Nina when he occasionally ran into her around the kibbutz.

But one evening, about six months after his mother died, he was taking a shortcut through the avocado orchard to the gymnasium when Nina came toward him. She walked with her head bowed, hugging herself as if everything around her was cold. Rafael stopped, tensing up for reasons he did not understand. Nina was in her own world and did not notice him. He saw the way she moved. That was his first impression: her quiet, sparing motion. The limpid, high forehead, and a thin blue dress that fluttered halfway down her shins.

The expression on his face when he recounted—

Only when they got closer did Rafael see that she was crying—quiet, muffled sobs—and then she noticed him and stopped, and curved inward. Their gazes entangled fleetingly and, one might sorrowfully add, inextricably. “The sky, the earth, the trees,” Rafael told me, “I don’t know…I felt like nature had passed out.”

Nina was the first to recover. She gave an angry puff and hurried away. He had time to glimpse her face, which had instantly shed all expression, and something inside him coursed toward her. He held out his hand after her—

I can actually see him standing there with his hand out.

And that is how he’s remained, with the outstretched hand, for forty-five years.

But that day, in the orchard, without thinking, before he could hesitate and trip himself up, he sprinted after her to tell her what he’d understood the moment he’d seen her. Everything had come to life inside him, he told me. I asked him to explain. He mumbled something about all the things that had fallen asleep in him during the years of his mother’s illness, and even more so after her death. Now it was all suddenly urgent and fateful, and he had no doubt that Nina would yield to him right then and there.

Nina heard his footsteps chasing her. She stopped, turned around, and slowly surveyed him. “What is it?” she barked into his face. He flinched, shocked by her beauty and perhaps also by her coarseness—and mostly, I’m afraid, by the combination of the two. That’s something he still has: a weakness for women with a bit—just a drop—of aggression and even crudeness. That spiciness. Rafael, Rafi—

Nina put her hands on her waist, and a tough street girl jutted out. Her nostrils widened, she sniffed him, and Rafael saw a delicate blue vein throbbing on her neck, and his lips suddenly hurt; that’s what he told me: they were literally stinging and thirsting.

Okay, I get it, I thought. I don’t need the details.

Tears were still glistening on Nina’s cheeks, but her eyes were cold and serpentine. “Go home, boy,” she said, and he shook his head no. She slowly moved her forehead toward his head, tracking it back and forth as if searching for precisely the right point, and he shut his eyes and then she butted, and he flew back and landed in the hollow of an avocado tree.

“Ettinger cultivar,” he specified the name of the tree when he told me the story, so that I wouldn’t forget, God forbid, that every detail in the scene was important, because that is how you construct a mythology.

Stunned, he lay in the hollow, touched the bump already growing on his forehead, then stood up dizzily. Since his mother’s death, Ra

fael had not touched anyone, nor had he been touched, except by the kids who fought with him. But this, he sensed, was something different. She’d come along to finally open up his mind and rescue him from the torture. Through the blinding pain, he shouted out what he had realized the moment he’d seen her, though he was amazed when the words left his mouth, insipid and crude. “Words the guys used,” he told me, “like ‘I wanna fuck you,’ that kind of thing.” So different from his pure, scrupulous thought. “But for a second or two I saw on her face that, despite the dirty language, she got me.”

And maybe that is what happened—how should I know? Why not give her the benefit of the doubt and believe that a girl born in Yugoslavia, who for a few years really was, as it later turned out, an abandoned child with no mother or father, could—despite those opening stats, or perhaps because of them—at a moment of kindness glance into the eyes of an Israeli kibbutz kid, an inward-looking boy, or so I imagine him at sixteen, a lonely boy full of secrets and intricate calculations and grand gestures that no one in the world knew about. A sad, gloomy boy, but so handsome you could cry.

Rafael, my father.

There’s a well-known film, I can’t remember what it’s called right now (and I’m not wasting a second on Google), where the hero goes back to the past to repair something, to prevent a world war or something like that. What I wouldn’t give to return to the past just to prevent those two from ever meeting.

* * *

—

Over the days and, mostly, the nights that came afterward, Rafael tormented himself about the marvelous moment he’d squandered. He stopped taking his mother’s sleeping pills so that he could experience the love unclouded. He searched all over the kibbutz, but he could not find her. In those days he hardly spoke to anyone, so he did not know that Nina had left the singles’ neighborhood, where she’d lived with her mother, and expropriated a little room in a moldering old shack from back in the founders’ days. The shack was like a train of tiny rooms, located behind the orchards, in an area that the kibbutzniks, with their typical sensitivity, called the leper colony. It was a small community of men and women, mostly volunteers from overseas, misfits who hung around without contributing anything, and the kibbutz didn’t know what to do with them.

But the notion that had germinated in Rafael when he met Nina in the orchard was no less impassioned, and it wrapped itself tighter and tighter around his soul by the day: If Nina agrees to sleep with me, even once, he thought in all earnestness, her expressions will come back.

He told me about that thought during a conversation we filmed an eternity ago, when he was thirty-seven. It was my debut film, and this morning, twenty-four years after shooting it, we decided, Rafael and I, in a burst of reckless nostalgia, to sit down and watch it. At that point in the film he can be seen coughing, almost choking, scouring his scruffy beard, unfastening and refastening his leather watch strap, and, above all, not looking up at the young interviewer: me.

“I have to say, you were very self-confident at sixteen,” I can be heard chirping ingratiatingly. “Me?” the Rafael in the film responds in surprise. “Self-confident? I was shaking like a leaf.” “Well, in my opinion,” says the interviewer, sounding horribly off-key, “it’s the most original pickup line I’ve ever heard.”

I was fifteen when I interviewed him, and for the sake of full disclosure I should say that until that moment I had never had the good fortune to hear any pickup line, original or trite, from anyone other than me-in-the-mirror with a black beret and a mysterious scarf covering half my face.

A videotape, a small tripod, a microphone covered with disintegrated gray foam. This week, in October of 2008, my grandmother Vera found them in a cardboard box in her storage attic, along with the ancient Sony through which I viewed the world in those days.

Okay, to call that thing a film is somewhat generous. It was a few haphazard and poorly edited segments of my father reminiscing. The sound is awful, the picture is faded and grainy, but you can usually figure out what’s going on. On the cardboard box, Vera had written in black marker: gili—various. I have no words to describe what that film does to me, and how my heart goes out to the girl I used to be, who looks—I’m not exaggerating—like the human version of a dodo, an animal that would have died of embarrassment had it not gone extinct. In other words, a creature profoundly out of whack in terms of what it is and where it’s headed—everything was up for grabs.

Today, twenty-four years after I filmed that conversation, as I sit watching it with my dad at Vera’s house on the kibbutz, I feel amazed by how exposed I was, even though I was only the interviewer and hardly ever appeared on-screen.

For quite a number of minutes I can’t concentrate on what my father is saying about him and Nina, about how they met and how he loved her. Instead I sit here next to him, folding over and shrinking back beneath the force of that internal conflict, projected unfiltered, like a scream, from inside the girl I used to be. I can see the terror in her eyes because everything is so open, too open, even questions like: How much life force does she contain, or how much of a woman will she be and how much of a man. At fifteen she still does not know which fate will be decided for her in the dungeons of evolution.

If I could make a brief appearance—this is what I think—just for a moment, in her world, and show her pictures of myself today, like of me at work or me with Meir, even now, in our state, and if I could tell her: Don’t worry, kid, in the end—with a couple of shoves, a few compromises, a little humor, some constructive self-destruction—you will find your place, a place that will be only yours, and you will even find love, because there will be someone who is looking for an ample woman with an air of the dodo about her.

* * *

—

I want to go back to the beginning, to the family’s incubators. I’ll squeeze in whatever I can before we take off for the island. Rafael’s father, Tuvia Bruck, was an agronomist who oversaw all the agricultural lands between Haifa and Nazareth and held senior positions on the kibbutz. He was a handsome, serious man of many deeds and few words. He loved his wife, Dushinka, and cared for her through her years of illness as best he could. After she died, people on the kibbutz began mentioning Vera, Nina’s mother, to him. Tuvia was hesitant. There was something foreign about her. Always, in any situation, she wore lipstick and earrings. Her accent was heavy, her Hebrew peculiar (it still is; no one else sounds like her), and even her voice sounded diasporic to him. An old friend from the Yugoslavian group put his arm on Tuvia’s shoulder one evening as they walked out of the dining hall and said, “She’s a woman of your caliber, Tuvia. You should know that she went through some things you would not believe, and there are things that still can’t be spoken of.”

Tuvia invited Vera to his apartment so they could get acquainted. To make things less awkward, she brought a friend, a woman from her hometown in Croatia who was an enthusiastic photographer. The two women sat quietly, with their legs crossed, in uncomfortable armchairs made of metal rods with a woven web of thin nylon cords that cut into their rear ends.

It took the self-control of a monk on a pillar for them to avoid laughing when Tuvia attempted to transport the refreshments his daughters had prepared out of the kitchen. Later, for thirty-two good years—happy years—together, Vera enjoyed impersonating him in those first moments, walking to the kitchen for a bowl of peanuts or pretzel sticks while regaling them with facts about Prodenia larvae and the leaf-miner moth, returning empty-handed, smiling apologetically with a charming dimple on his left cheek, then heading back to the kitchen for a vase of wildflowers.

While Rafael’s father performed his convoluted mating dance, Vera looked around and tried to learn something about his late wife. There were no pictures on the walls, nor any bookshelves or rugs. The lampshade on the floor lamp was moth-eaten (she wondered if it was a leaf-miner moth), and strips of pale-yellow foam poked out of the sofa. Vera’s

friend thrust her chin at a folded-up wheelchair and an oxygen tank, which were wedged between the sofa and the wall. Vera sensed that the illness that had permeated the home for years had not yet fully retreated. Some part of it was still unfinished. The knowledge that she had an adversary made her sit up straighter, and she commanded Rafael’s father to finally sit down and talk to them properly. He dropped to the sofa and sat erect, with his arms crossed over his chest.

Vera smiled at him from the depths of her womanhood, and his spine began to melt. The friend started to feel redundant and stood up to leave. She and Vera exchanged a few words in fluid Serbo-Croatian. Vera shrugged her shoulders and gave a dismissive wave that seemed to say, I don’t actually mind that at all. Tuvia, whose entire existence was being swiftly assessed, was a firm and confident man, but he now felt undermined by this little woman with the sharp green eyes. So sharp that every so often one had to look away. Before she left, the friend asked for permission to photograph them with her Olympus. They were both embarrassed, but she said, “You look so lovely together,” and they glanced at each other and for the first time saw the possibility of themselves as a couple.

Vera got up from the torture chair and sat down next to Tuvia on the narrow sofa. In the black-and-white photograph, she leans back on one arm, looking sideways at him with a certain remoteness, and smiles. She seems to be teasing him and enjoying it.

That was 1963, early winter: Vera is forty-five. A stray curl droops over her forehead, her lips are full and perfect. She has narrow eyebrows, Hedy Lamarr eyebrows, penciled on. Tuvia is fifty-four, wearing a white shirt with a broad collar and a handmade cable-knit sweater. He has a thick black forelock with a very straight part. His giant fists are crossed over his chest. He looks awkward, and his forehead glistens with excitement. His legs are crossed, and only now do I notice, looking at the picture, that under the table (a plank perched on two wooden crates, covered with a white cloth), Vera’s right toe, in a strappy sandal, is slightly touching the sole of Tuvia’s left shoe, almost tickling it.