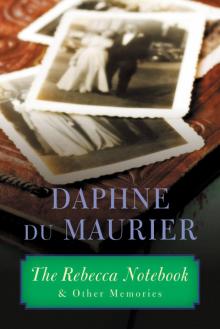

The Rebecca Notebook

Daphne Du Maurier

THE REBECCA NOTEBOOK

AND OTHER MEMORIES

Daphne du Maurier

Foreword by Alison Light

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Foreword

In the late 1920s a young woman from London falls in love with a deserted mansion hidden in the Cornish woods in the far west of England. Her family have bought a holiday place nearby and so she goes back whenever she can, revisiting the abandoned property, and harbouring the fantasy of one day living there. Eventually she pesters the absent landlord and gets permission to walk in the grounds, but nothing is done to save the house which falls gently into disrepair. The house lives on in her imagination and then, miraculously, many years later, her wish comes true—she acquires the lease, restores the mansion to its former glory, and makes it her home. By now it is wartime and the girl has become a wife and mother but she is also Daphne du Maurier, whose bestseller, Rebecca, has recently been a Hollywood success. Celebrating her arrival at ‘Menabilly’, du Maurier writes proudly ‘the house belongs to me’ and yet the author of ‘The House of Secrets’, one of the essays reprinted here, ends her account on a characteristic note of suspense. Du Maurier is only a tenant and her happiness, like her home, is surely temporary. ‘It cannot last,’ she writes, ‘it cannot endure’. Fans of du Maurier’s fiction know that in her world disenchantment is the price we pay for the magic: ‘it is the very insecurity of the love that makes the passion strong’.

When she peered through the windows into Menabilly’s forlorn and damp rooms, du Maurier wondered ‘Where was the laughter gone? Where were the voices that had called along the passages?’ This volume of short pieces about her family, her life and beliefs, is prompted, like so many of her stories, by the desire to reanimate the past. Daphne du Maurier’s was a Romantic temperament, not because she penned exotic tales or swashbuckling costume dramas, and certainly not because she believed in fairytale endings for men and women (‘there is no such thing as romantic love’, she declares provocatively in another of the essays here); rather, she was moved by what the poet Shelley called ‘mutability’, the inevitable changefulness of things. For du Maurier change was always ominous. The spirit of a place haunted her, its ghosts were an eerie consolation that human loves and attachments were never wholly lost.

This collection opens with ‘The Rebecca Notebook’, du Maurier’s original plans for her most famous novel. Du Maurier began Rebecca when she was an itinerant army-wife stationed with her husband in Egypt and homesickness seeps into the descriptions of Cornwall (her longed-for Menabilly became ‘Manderley’ in the novel, another house of secrets where the shy heroine feels like a guilty trespasser). Typically she wrote the disillusioned epilogue first. Mr and Mrs de Winter are introduced as a middle-aged couple of dull English ‘expats’ living humdrum lives in hotels abroad, a sad pair longing for news of the cricket and pining for the English countryside. The final published version made it less parochial, changing the stodgy-sounding ‘Henry’ to the more glamorous and international ‘Maxim’. Du Maurier also wisely cut those lengthy passages where her narrator snobbishly disparages the nouveaux riches who have turned Manderley into a country club with a golf course and cocktail lounge. The melodramatic ending was dropped and eventually the epilogue became a prologue, tightening the psychological screws, as if the heroine were compulsively retelling the crime-story at the heart of her marriage. ‘We can never go back’, she says at the beginning of the novel, launching into retrospect.

Rebecca was published in 1938. Apart from the Notebook, the ‘memories’ gathered here date from du Maurier’s later life when most of her bestsellers were behind her. She begins with accounts of her family, a memoir of her French grandfather, George du Maurier, whose novel of Bohemian Paris, Trilby, was the smash-hit of the 1890s (though his fame is now as faded as the drawings he produced for Punch), and of her father, Gerald, the leading actor and theatre-manager of his day. Daphne had boldly written his biography not long after his death in 1934. ‘The Matinee Idol’, nearly forty years later, is a generous portrait of this childlike, affectionate, demanding man, for whom life was always a matter of ‘pretending to be someone else’. Nostalgic vignettes, these memoirs are tinged like sepia photographs with a faded charm, and with du Maurier’s bittersweet feeling for the transient—the ephemeral nature of an actor’s performances or the dying fall of her grandfather’s tenor floating out into the Victorian twilight. They are also a disgruntled lament for the disappearance of ‘Victorian values’, lost, she maintains, ‘through our own fault’. Temperamentally at odds with a more egalitarian postwar Britain, du Maurier distances herself here as she does in ‘My Name in Lights’ from the current ‘age of meagre mediocrity’ with its meretricious notions of instant celebrity. The enjoyment of success, she believed, should be very private—‘like saying one’s prayers or making love’.

Growing up in the 1900s, Daphne du Maurier was of that generation of Edwardian girls who envied and adored their male peers (in her autobiography she made no bones about wanting to be a boy). ‘Sylvia’s Boys’ is her tribute to her cousins, the Llewelyn-Davieses, who were fostered by J.M. Barrie and were the inspiration for his Peter Pan (the play in which Gerald took the parts of both the paterfamilias and of the sinister Captain Hook). Like her father’s brother, Guy, killed in the ‘Great War’, they seemed to her straightforwardly and delightfully male (Gerald, on the other hand, in his stage make-up was never quite a proper man). Daphne’s models of independence were always masculine and once she had discovered Cornwall, she abandoned the bright lights of London to learn to sail a boat, wear trousers, go fishing and exploring, shocking her neighbours and her family. In imagination at least, Daphne identified with the artists and adventurers amongst the du Mauriers. Nevertheless she held old-fashioned views of men and women and longed for a settled home life. ‘This I Believe’, presumably written for this volume, upholds ‘the law of the family unit’ as the strongest in life and is ambivalent about women’s emancipation. Not surprisingly, perhaps, when she fell in love, it was with a man in uniform, the young Major Frederick Browning, ‘Boy’ or ‘Tommy’, as Daphne called him.

In du Maurier’s novels the men are often cheats and bullies, the women fools for love (Rebecca is a story about murderous husbands as well as jealous and vicious wives). Psychological violence (though there is actual violence too) seemed inevitable given what was seen as a ‘sex war’, a battle for power or dominance which must at best end in stalemate. Margaret Forster’s biography of du Maurier tells us that her marriage was often turbulent, that her husband was unfaithful, and that she fell in love with women as well as men (how she would have hated these ‘revelations’!). Du Maurier’s autobiography, Growing Pains: The Shaping of a Writer (reprinted as Myself When Young) is far more reticent, focussing on her escape from her parents’ milieu and her intense and sometimes stifling relationship with her father. Her own marriage in 1932 closes the volume and a sequel was never written. All the more moving, therefore, is her memoir ‘Death and Widowhood’. She writes unflinchingly about the pain of losing a relationship of thirty-three years—‘the greater half’ of her existence, identifying with her dead husband by wearing his shirts, sitting at his d

esk and using his pen. Du Maurier is uncompromising, insisting that remarriage is unthinkable; that loneliness and suffering must be embraced. She believed she could no longer produce fiction, though there were other novels, and the morbid horrors of her story ‘Don’t Look Now’ derived from her own mourning. If in her sixties and seventies du Maurier turned more to autobiography, however veiled, that too, like this memoir, was a response to loss, a way of reinventing herself.

The Rebecca Notebook and Other Memories was Daphne du Maurier’s last book, published in 1981 when she was seventy-four (she died in 1989). The original bookjacket warns the reader that her views might be ‘surprising’. Perhaps only a fear of going out of circulation (a species of authorial death) could have persuaded her to write so personally, especially given her avowed loathing of publicity. There are longueurs, but du Maurier can be the best of company in her memoirs precisely because she refuses to curry favour (her patrician dismissal of her fans as ‘the mob’ might make any publisher nervous). She never patronises the reader and she never stays long on her high horse. If the picture emerges of a woman who grew more conservative with age, she also remained an individualist, as unmoved by fashion as she was in her girlhood. And she was able to laugh at herself.

The final trio of pieces offer a robust, unsentimental vision of growing old. After twenty-six years du Maurier had to leave her beloved Menabilly for Kilmarth, one of the estate’s former dower houses (she describes the upheaval in ‘Moving House’). Du Maurier’s Cornwall is always stormy and unpeopled (like the moors of her favourite authors, the Brontë sisters); its beauties harsh yet vulnerable (Vanishing Cornwall was the title of the book she wrote in her last years about her cherished, adopted county). ‘A Winter’s Afternoon in Kilmarth’ gives short shrift to the Tourist Board fantasy of a sunny Cornish ‘Riviera’ (an image now replaced by that of surfing and gourmet fish restaurants). Battling against wind and rain, in what was almost her uniform of military jersey and cap, a soldierly figure with her dog, du Maurier enjoyed the sensation of splendid isolation on a teemingly wet hillside—upright and formidable, taking life on the chin. The fantasy of going it utterly alone could be the compensation for those times which were also deeply lonely and bereft.

All writers lead double lives. As Lady Browning, wife of a General who became a royal aide to the Duke of Edinburgh, as well as a worldwide bestselling author for nearly fifty years, Daphne du Maurier was often in the public eye. Yet being anonymous and unobserved was crucial to her. Du Maurier’s Cornwall was her home but it was also a country of the mind, the place where she could be a restless spirit and a writer in retreat. She needed to be reclusive in order to enjoy ‘the secret nourishment’ of writing; limelight, she believed, was a bad light to work in. Her poem of 1926, ‘The Writer’, composed before she had begun her first novel, projects a future for herself. It paints a picture of the solitary, self-sufficient life of a writer, the woman whose room of her own gives her the psychic and emotional room she craves. There is menace here too. Being a writer is imagined as a life without secure ties, involving an obliteration of the self, ‘the thread of the spider who spins on the wall/ Who is lost, who is dead, who is nothing at all’.

Why do writers write? What compels them to this strange self-absorbed, self-effacing life? Du Maurier’s stories take us into the shuttered places in human psychology where hidden or repressed feelings—jealousy, rage, lust, terror—threaten to overwhelm us, or like love and desire, to transport us into another dimension. Like a medium at a seance, du Maurier felt taken over by writing, ‘possessed’ by her plot and her characters. That activity, leaving the world, as she calls it, meant losing one’s boundaries and yet somehow retaining control. We all fantasise and we all live in our fantasies, imagining we are the authors of our lives, but the novelist makes something lasting and shared of her daydreams. A writer’s memoirs or biography will always fascinate us because it offers tantalising glimpses of this mysterious process. Yet however much we learn, the writing life remains a house of secrets. We press our faces to the glass, frustrated and intrigued, seeing only shadows and our own reflection.

Alison Light

London, 2004

The Rebecca Notebook and Epilogue

Introduction to The Rebecca Notebook and Epilogue

It is now over forty years since my novel Rebecca was first published. Although I had then written four previous novels, The Loving Spirit, I’ll Never Be Young Again, The Progress of Julius and Jamaica Inn, as well as two biographies, Gerald: A Portrait and The du Mauriers, the story of Rebecca became an instant favourite with readers in the United Kingdom, North America and Europe. Why, I have never understood! It is true that as I wrote it I immersed myself in the characters, especially in the narrator, but then this has happened throughout my writing career; I lose myself in the plot as it unfolds, and only when the book is finished do I lay it aside, I may add, finally and forever.

This has been more difficult with Rebecca, because I continue to receive letters from all over the world asking me what I based the story on, and the characters, and why did I never give the heroine a Christian name? The answer to the last question is simple: I could not think of one, and it became a challenge in technique, the easier because I was writing in the first person.

I was thirty years old when I began the story, jotting down the intended chapters in a notebook, and I am now in my seventy-fourth year, with memory becoming hazier all the time. I apologise for this, but it cannot be helped. All I can tell the reader is that in the fall of 1937 my soldier husband, Boy Browning, was commanding officer of the Second Battalion, Grenadier Guards, which was stationed in Alexandria, and I was with him. We had left our two small daughters, the youngest still a baby, back in England in the care of their nanny, with two grandmothers keeping a watchful eye.

Boy—Tommy to me—and I were living in a rented house, not far from the beach, Ramleh I believe it was called, and while he was occupied with military matters I was homesick for Cornwall. I think I put a brave face on the situation and went to the various cocktail parties which we were obliged to attend, but all I really wanted to do was to write, and to write a novel set in my beloved Cornwall. This novel would not be a tale of smugglers and wreckers of the nineteenth century, like Jamaica Inn, but would be set in the present day, say the mid-twenties, and it would be about a young wife and her slightly older husband, living in a beautiful house that had been in his family for generations. There were many such houses in Cornwall; my friend Foy Quiller-Couch, daughter of the famous ‘Q,’ with whom I first visited Jamaica Inn, had taken me to some of them. Houses with extensive grounds, with woods, near to the sea, with family portraits on the walls, like the house Milton in Northamptonshire, where I had stayed as a child during the First World War, and yet not like, because my Cornish house would be empty, neglected, its owner absent, more like—yes, very like—the Menabilly near Fowey, not so large as Milton, where I had so often trespassed. And surely the Quiller-Couches had told me that the owner had been married first to a very beautiful wife, whom he had divorced, and had married again a much younger woman?

I wondered if she had been jealous of the first wife, as I would have been jealous if my Tommy had been married before he married me. He had been engaged once, that I knew, and the engagement had been broken off—perhaps she would have been better at dinners and cocktail parties than I could ever be.

Seeds began to drop. A beautiful home… a first wife… jealousy… a wreck, perhaps at sea, near to the house, as there had been at Pridmouth once near Menabilly. But something terrible would have to happen, I did not know what… I paced up and down the living room in Alexandria, notebook in hand, nibbling first my nails and then my pencil.

The couple would be living abroad, after some tragedy, there would be an epilogue—but on second thoughts that would have to come at the beginning—then Chapters One, and Two, and Three… If only we did not have to go out to dinner that night, I wanted to think…

And so it started, drafts in my notebook, and the first few chapters. Then the whole thing was put aside, until our return to England in only a few months’ time.

Back home, Tommy and his battalion were stationed at Aldershot, and we were lucky enough to rent Greyfriars, near Fleet, the home of the great friend in the Coldstream Guards who had taken over from Tommy in Alexandria. Reunited with the children, and happy in the charming Tudor house, I was able to settle once more to my novel Rebecca. This much I can still remember: sitting on the window seat of the living room, typewriter propped up on the table before me, but I am uncertain how long it took me to finish the book, possibly three or four months. I had changed some of the names too. The husband was no longer Henry but Max—perhaps I thought Henry sounded dull. The sister and the cousin, they were different too. The narrator remained nameless, but the housekeeper, Mrs Danvers, had become more sinister. Why, I have no idea. The original epilogue somehow merged into the first chapter, and the ending was entirely changed.

So there it was. A finished novel. Title, Rebecca. I wondered if my publisher, Victor Gollancz, would think it stupid, overdone. Luckily for the author, he did not. Nor did the readers when it was published.

Its success was such that a year later I adapted the story for the stage, then later the film rights were sold. War came in 1939. We had moved from Greyfriars to Hythe, to the Senior Officers’ School where Tommy became commandant. I forgot all about Rebecca, if its readers had not. And it may have been because of its popularity that I was asked, some eight years later, to contribute an article to a book entitled Countryside Character. I called my article ‘The House of Secrets,’ and this can be read in the present volume.

And what became of the original notebook? That is another matter, which I will tell briefly.