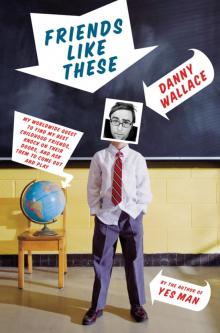

Friends Like These: My Worldwide Quest to Find My Best Childhood Friends, Knock on Their Doors, and Ask Them to Come Out and Play

Danny Wallace

Also by Danny Wallace

Yes Man

Are You Dave Goreman? (with Dave Goreman)

Join Me

Random Acts of Kindness

Copyright

Copyright © 2008, 2009 by Danny Wallace

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

First eBook Edition: September 2009

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN 978-0-316-08199-3

For Greta

My best friend

And in memory of the

great and loved David McMahon

“If a man has no tea in him, he is incapable

of understanding truth and beauty.”

JAPANESE PROVERB

Contents

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter One: In Which We Experience an Earthquake…

Chapter Two: In Which We Learn That Nobody Moves to Chislehurst…

Chapter Three: In Which We Learn The Sad Fact That Sometimes, It’S Not Possible to Be Friends Forever…

Chapter Four: In Which We Learn That Growing Up Is Less Worrying When You Realize That Everyone’s Doing It…

Chapter Five: In Which We Learn That Daniel Has Lost His Youthful Menace…

Chapter Six: In Which We Learn That Quite Often, the Truth Is Rubbish…

Chapter Seven: In Which We Learn That Where There Are Acronyms, There Is Hope (WTAATIH)

Chapter Eight: In Which We Discover That for Every Hitler, There’s a Shitler…

Chapter Nine: In Which We Learn That When You Look Back, Most of Your Mates Do Work In I.T.…

Chapter Ten: In Which We Learn That Every Day, a Million Coincidences Nearly Happen…

Chapter Eleven: In Which We Learn That Often, the Future Takes Ages…

Chapter Eleven-and-a-Half: In Which We Learn the Power of Persuasion…

Chapter Twelve: In Which We Learn That a Friend Is Worth a Flight…

Chapter Thirteen: In Which We Learn That You Can Often Catch Danny Rubbadubbin’ in a Club With Some Bubbly…

Chapter Fourteen: In Which We Learn That Hardcore Rap Is Seldom Romantic…

Chapter Fifteen: In Which We Learn That Sometimes Secrets Should Stay Secret…

Chapter Sixteen: In Which We Learn That Not Every Thing Can Go Your Way, All the Time…

Chapter Seventeen: In Which We Learn How to Stop…

Chapter Eighteen: In Which We Learn That No One Ever Dreams about Cabbage…

Chapter Nineteen: In Which You May Be Surprised to Learn That Daniel Is Not at HOME…

Chapter Twenty: In Which We Learn That It Is Better to Travel Hopefully Than to Arrive Disenchanted…

Chapter Twenty-One: In Which We Meet Someone Unexpected…

Epilogue: Teaching Moments

Danny Would Like To Thank…

Prologue

“I think you should get a will,” said the man.

“A will?” I said. “I’m only twenty-nine!”

“Doesn’t matter. You’re nearly thirty. Statistically, most people die above the age of thirty.”

“Do they?” I said, horrified.

“Statistically, yes. Do you own a house?”

“I’ve just bought one!” I said.

“A car?”

“Yes!”

“Do you have a wife?”

“Only a small one.”

“Doesn’t matter. You should get a will.”

“Do you have a will?” I asked.

“No,” said the man. “I’m only twenty-eight.”

This was just one of many similar conversations I would suddenly be having on my way to turning thirty, during a time in which I’d begun to question the way my life was going. I’m not saying I was unhappy—I wasn’t, I was very happy—but I was beginning to feel unnerved.

Growing up is a strange thing to happen to anybody. And it does. To almost everybody. And for me, the way to cope with it became quite simple—to look back.

I was worried, when I wrote the following pages down, that you might not be all that interested in the people I met. That perhaps they might be too specific to me for them to matter to you. But then I realized—the more specific I was being, the more general everything was becoming… childhood, for example, and adolescence, and hopes and wishes, and friendship, and maturity… but if they don’t strike any chords, there’s a car chase and some ninjas for you, too.

The people you’re about to meet are some of the people I grew up with, in ordinary schools, in ordinary places, in ordinary times. Wherever possible, and in the vast majority of cases, I’ve kept their names and details real—on those rare occasions where someone’s asked me to change a name or detail, I’ve done so, and in one case in particular I’ve taken the decision myself, in the interests of privacy. Sometimes I’ve also had to move a date or event around a bit, but this is just so that you don’t get bored and fall asleep too easily. I know what you’re like.

Hey, wow—I’ve just noticed—what excellent shoes you’re wearing. They really set off your eyes.

This, then, is the story of a summer in my life that came to sum up all the summers of my life, and perhaps prepared me a little for all the summers to come.

I still don’t have a will, by the way. But I think I did find my way.

See you in there.

Danny Wallace

Augsburger Strasse, Berlin

CHAPTER ONE

IN WHICH WE EXPERIENCE AN EARTHQUAKE…

There are moments in life when you come to question your actions. Moments of outstanding clarity and purest thought, when you look around you, you take in your environment, you work out what brought you here, and you decide that something is wrong.

For me, it was happening right now.

Right now, right this very second, in the middle of a harsh and sparse Japanese countryside, a little over a week before my thirtieth birthday, past a town I didn’t know the name of, full of people whose names I couldn’t pronounce.

My address book—a battered black address book with just twelve names in; an address book that had taken me around Britain, to America, Australia and now here—had proved useless this time.

It was four o’clock and I looked around me. I took in my environment. I worked out what had brought me here. And I decided that something was wrong.

Here I was, standing in a rice field under a mountain in the afternoon sun, a Westerner in the far, far East, wearing grubby sneakers, mud-flecked jeans and a T-shirt with the face of a small Japanese boy on it.

And I was lost.

I dug into my pocket and pulled out the document I’d brought with me.

I looked at it.

An Investigation on the Influence of Vitreous Slag Powders on Rheological Properties of Fresh Concrete

I stared at it for a moment, then put it away again. It wasn’t helping.

But th

ere—there, in the distance, just beyond a scattering of houses and a girl on a bike, I saw something. A hospital. A vast, bright white block. This was what I needed. This was what I had come for.

Because in that building—in that hospital—was a man I needed to meet. A man I had traveled ten thousand miles to shake hands with. A man who went to my school for six months in the 1980s, who I’d last seen twenty years ago in a McDonald’s in England’s East Midlands, and who had absolutely no idea whatsoever that I was currently tramping through a Japanese rice field a quarter of a mile away to meet him. A man whose face I had on my T-shirt.

In the past few months I had met royalty. Rappers. A man who thinks he’s solved time travel. I’d dressed as a giant white rabbit and I’d fought off a ninja.

And now… now I was going to meet Akira Matsui.

And I was going to meet Akira Matsui whether he liked it or not.

My decision to track down a Japanese man I hadn’t seen since the days of Autobots and Optimus Prime started with a text message, six months earlier. A text message telling me there was some important news. Important news I could only be told face to face.

I didn’t know it then, but it was going to be quite a week for important news.

I’d recently moved house. Only a few miles on a map, but in London terms I had moved to a whole new world. No longer was I in the East End—an area I’d lived in for six years, where I’d become slowly and subtly used to the deafening thunder of the trains and the police sirens reminding you every few minutes that somewhere not too far away someone’s been naughty. I was no longer living in the shadow of the apartment blocks which hid the sun from me four times a day but stood guard over me all the same. No longer a short walk from one of the nicest pubs in London, where Wag and Ian and I would spend long and lazy Sunday afternoons trying to flick peanuts into pint glasses or comparing notes on our important philosophies and ideas. Brick Lane, with its mile upon mile of curry houses, was now just out of convenient reach. Spital-fields Market, once round the corner, became somewhere we’d go next weekend, rather than this. And, perhaps most harrowingly, I was now no longer within free delivery range of Mr. Wu’s World of Meat. My world had been turned upside down.

I knew I’d miss it. And I was right. I missed it. I’m just not sure I knew I missed it.

For the time being, I’d been seduced. Seduced by a smart new area of north London. An area which was going places. An area where people did brunch, and drank lattes, and dined at Latvian restaurants, and drove long, silver cars, and wore Carhartt hoodies to make people think they were urban, and put everything apart from their house on the expense account. Where the men wore media glasses and the ladies wore skinny jeans and ate croissants and read the papers on a Sunday morning in a place with a battered leather couch before having a walk around middle-class antique stalls, with their thimbles and spoons. And everyone was married. Everyone! I liked it, but I found it laughable—this row upon row of cliché I had inadvertently stumbled into. What must they make of me here? I said one Sunday morning, over brunch, to Lizzie, my wife.

“What do you mean?” she said.

“I mean, what do you think they make of me here?” I giggled. “Of us?”

Lizzie put down her newspaper, and I tore off another piece of croissant. I dipped it gingerly into my latte and raised my eyebrows. I was a bloody maverick.

“Who?”

“These married clichés,” I said. “These thirtysomething media-glasses-wearing clichés in their Carhartt hoodies and their skinny jeans?”

“You’re wearing a Carhartt hoodie,” said Lizzie, with a smile.

“Yes, I’m wearing a Carhartt hoodie, yes, but I imagine I’m doing it ironically. Anyway, I’m urban, aren’t I?”

She wrinkled her nose.

“You’re not very urban.”

“I’m urb-ish.”

“You’re also nearly thirty and you’re wearing media glasses.”

“These are not media glasses. These are merely glasses that are shaped like media glasses. At least I’m not wearing skinny jeans. I could be wearing skinny jeans! Then I’d be a cliché.”

“I’m wearing skinny jeans.”

“Yes. You are. That’s true.”

I shifted around on the battered leather couch.

“Shall we have a walk around the antique stalls?”

“How do you ask for the bill in Latvian?”

The changes had started to happen without anyone noticing. But like the birds escaping the trees at the first fraction of a distant earthquake, the signs had been there, for anyone to pick up on, from the beginning. Just small things. Like the day I’d had to look up the number of a builder to do some work on our new little house. Looking up the number of a builder is the first step towards actually employing someone. I would be in charge of someone. A man. A proper man, with paint on his fingers and stubble on his chin. I’d be a boss.

And then there was the morning Lizzie witnessed something terrifying.

“What are you doing?” she’d said, wide-eyed, as she watched me walking to the kitchen.

“I’m just taking this mug to the sink,” I’d said.

And then, as we realized what was happening—what that signified—how that was the first time in my life I had ever taken a mug to the sink within two days of finishing my tea—I stopped dead in my tracks and we both simply stared at each other in horror.

We had felt the first tremors of the earthquake. It was getting closer.

Soon, the evidence of impending adulthood began to pile up. The fridge was our early warning system. Gone were the frankfurters and processed cheese of just a year or two before—replaced by skimmed milk, and hummus, and baby carrots, and fresh spinach. We’d gone organic, we were buying fairtrade, we had crisp white wine instead of cans of beer. Clubs had become bars, nights down the pub had slowly morphed into intimate dinners with close friends. I ate low-fat pretzels with crushed rock salt where once Doritos would have done. How had this happened? Was it the move? Or was it the fact that I was twenty-nine? On the brink of change? On the brink of finally, undeniably, irrefutably becoming… a man?

But I wasn’t a man. I was a boy. I had a silly job, for starters. A job I’d entered into quite without meaning to, through a slightly odd set of circumstances. A job which gets strange looks. A job I’m slightly embarrassed to tell you about. A job which changed title every time I completed a new piece of work, but which, at the moment at least, you could sort of describe as “very minor television personality” if you were being kind, and “quiz show host” if you were not.

I told you it was silly.

Since I’d started popping up on shows, asking questions and providing answers, my friends had started to think of me as someone good to get on a pub quiz team—despite the fact that I have never in my life won a pub quiz. People texted me questions asked by trivia machines in burger bars. Cabbies asked me to settle bets. I’d become recognizable on the streets, but only to people who thought they’d gone to school with me or met me at a wedding, or actually had gone to school with me or met me at a wedding. I was especially recognizable to them.

But it was fun. It was a different me, though. I had to pretend to be confident and in control and knowledgeable, but I felt a little like a fraud. Sometimes I wondered if I knew who the real me was. But still, it left me with a great deal of down-time. I knew in the spring I’d be tackling a big new project, so for now I was happy bumbling about, writing the odd piece for a newspaper or magazine to keep the bills paid, seeing Wag and Ian when I could, and trying somehow to convince myself I was able to handle DIY. It was time I should have been investing wisely, to be honest. And yet I was doing nothing to stop this constant slide into domesticity…

So for weeks the rumble got louder. We’d started buying fresh bread. We’d visited a farmers’ market and bought some olives, despite the fact that very few local farmers have ever actually farmed an olive. I wanted to talk to Lizzie about what was happening,

but she seemed so comfortable, so at ease with it all, so in her element, that it never seemed the right time. She brought home display cushions. She bought some sticks which she stuck in a jar and convinced me were a “dramatic focal point” for our living room. She bought the box set of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s critically acclaimed Trois Couleurs trilogy, which she assured me would explore the French Revolutionary ideals of freedom, equality and brotherhood and their relevance to the contemporary world, and I’d smiled and hidden the copy of Kung Fu Soccer I’d bought that afternoon in HMV.

But these were all foreshocks… mere tremors before the main event. The day the earthquake threatened its arrival proper was the day my phone, sitting above the very epicenter of it all, jolted violently around the table, in controlled, mea sured spasms. Either there really was an earthquake, or I’d had a text.

Come round to ours on Friday night! It’s a book launch! And we’ve got something we’d love to ask you…

It was from our friends Stefan and Georgia. Two names which prove, even more than a casual dunk of a croissant in a latte, that we were now operating in a whole different world. Were we still in the East End, I have no doubt that that text would have been from Blind Eric and Jimmy the Lips, inviting us out to throw traffic cones at cars.

The Friday arrived the way Fridays do, and we’d gone along to their vast Highbury mansion to find that Stefan, a chef, had prepared an elaborate spread of unusual dishes. It was all in aid of his latest cookbook, and felt very fancy and posh and middle class. Now, Stefan is a man who likes his food slightly odd. I know this because I once ate some soup at his house and on the third spoonful discovered a severed fish head staring back at me. He is yet to offer an after-dinner counseling service, but it can only be a matter of time before the authorities make it a legal requirement. So, as a joke, I’d brought along instant noodles, “just in case there’s anything I don’t like!” Stefan laughed and I laughed and Lizzie laughed. I can be quite funny sometimes. But then he looked a little offended and put it in a cupboard.