Hidden Water

Dane Coolidge

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online DistributedProofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

"I never saw a sheepman yet that would fight, but you'vegot to"]

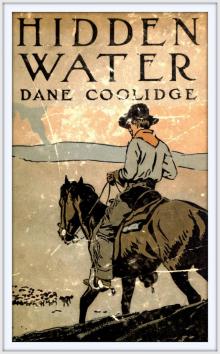

HIDDEN WATER

By DANE COOLIDGE

With Four Illustrations in Color

By MAYNARD DIXON

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers--New York

COPYRIGHT

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1910

Published October 29, 1910

Second Edition, December 3, 1910

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London, England

All rights reserved

ILLUSTRATIONS

"I never saw a sheepman yet that would fight, but you've got to" _Frontispiece_ "Put up them guns, you gawky fools! This man ain't going to eat ye!" 177 "No!" said Kitty, "you do not love me" 287 Threw the sand full in his face 462

HIDDEN WATER

CHAPTER I

THE MOUSE

After many long, brooding days of sunshine, when the clean-cutmountains gleamed brilliantly against the sky and the grama grasscurled slowly on its stem, the rain wind rose up suddenly out ofPapagueria and swooped down upon the desolate town of Bender, whirlinga cloud of dust before it; and the inhabitants, man and horse, took tocover. New-born clouds, rushing out of the ruck of flying dirt, cast acold, damp shadow upon the earth and hurried past; white-crestedthunder-caps, piling-up above the Four Peaks, swept resolutely down tomeet them; and the storm wind, laden with the smell of greasewood andwetted alkali, lashed the gaunt desert bushes mercilessly as it howledacross the plain. Striking the town it jumped wickedly against the oldHotel Bender, where most of the male population had taken shelter,buffeting its false front until the glasses tinkled and the barmirrors swayed dizzily from their moorings. Then with a suddenthunder on the tin roof the flood came down, and Black Tex set up thedrinks.

It was a tall cowman just down from the Peaks who ordered the round,and so all-embracing was his good humor that he bid every one in theroom drink with him, even a sheepman. Broad-faced and huge, with fourmonths' growth of hair and a thirst of the same duration, he stood atthe end of the bar, smiling radiantly, one sun-blackened hand toyingwith the empty glass.

"Come up, fellers," he said, waving the other in invitation, "anddrink to Arizona. With a little more rain and good society she'd be aholy wonder, as the Texas land boomer says down in hell." They came upwillingly, cowpunchers and sheepmen, train hands, prospectors, and thesaloon bums that Black Tex kept about to blow such ready spenders ashe, whenever they came to town. With a practised jolt of the bottleTex passed down the line, filling each heavy tumbler to the brim; hepoured a thin one for himself and beckoned in his roustabout to swellthe count--but still there was an empty glass. There was one man overin the corner who had declined to drink. He sat at a disused cardtable studiously thumbing over an old magazine, and as he raised hisdram the barkeeper glowered at him intolerantly.

"Well," said the big cowboy, reaching for his liquor, "here's how--andmay she rain for a week!" He shoved back his high black sombrero as hespoke, but before he signalled the toast his eye caught the sidelongglance of Black Tex, and he too noticed the little man in the corner.

"What's the matter?" he inquired, leaning over toward Tex and jerkinghis thumb dubiously at the corner, and as the barkeeper scowled andshrugged his shoulders he set down his glass and stared.

The stranger was a small man, for Arizona, and his delicate hands werealmost as white as a woman's; but the lines in his face were gravendeep, without effeminacy, and his slender neck was muscled like awrestler's. In dress he was not unlike the men about him--Texas boots,a broad sombrero, and a canvas coat to turn the rain,--but his mannerwas that of another world, a sombre, scholarly repose such as youwould look for in the reference room of the Boston Public Library; andhe crouched back in his corner like a shy, retiring mouse. For amoment the cowman regarded him intently, as if seeking for someexculpating infirmity; then, leaving the long line of drinkers tochafe at the delay, he paused to pry into the matter.

"Say, partner," he began, his big mountain voice tamed down to amasterful calm, "won't you come over and have something with us?"

There was a challenge in the words which did not escape the stranger;he glanced up suddenly from his reading and a startled look came intohis eyes as he saw the long line of men watching him. They were largeclear eyes, almost piercing in their intentness, yet strangelyinnocent and childlike. For a moment they rested upon the regal formof the big cowboy, no less a man than Jefferson Creede, foreman of theDos S, and there was in them something of that silent awe and worshipwhich big men love to see, but when they encountered the black looksof the multitude and the leering smile of Black Tex they lit upsuddenly with an answering glint of defiance.

"No, thank you," he said, nodding amiably to the cowman, "I don'tdrink."

An incredulous murmur passed along the line, mingled with sarcasticmutterings, but the cowman did not stir.

"Well, have a cigar, then," he suggested patiently; and the barkeeper,eager to have it over, slapped one down on the bar and raised hisglass.

"Thank you just as much," returned the little man politely, "but Idon't smoke, either. I shall have to ask you to excuse me."

"Have a glass of milk, then," put in the barkeeper, going off into aguffaw at the familiar jest, but the cowboy shut him up with a look.

"W'y, certainly," he said, nodding civilly to the stranger. "Come on,fellers!" And with a flourish he raised his glass to his lips as iftossing off the liquor at a gulp. Then with another downward flourishhe passed the whiskey into a convenient spittoon and drank his chaserpensively, meanwhile shoving a double eagle across the bar. As BlackTex rang it up and counted out the change Creede stuffed it into hispocket, staring absently out the window at the downpour. Then with amuttered word about his horse he strode out into the storm.

Deprived of their best spender, the crowd drifted back to the tables;friendly games of coon-can sprang up; stud poker was resumed; and acrew of railroad men, off duty, looked out at the sluicing waters andidly wondered whether the track would go out--the usual thing inArizona. After the first delirium of joy at seeing it rain at allthere is an aftermath of misgiving, natural enough in a land where thewhole surface of the earth, mountain and desert, has been chopped intoditches by the trailing feet of cattle and sheep, and most of thegrass pulled up by the roots. In such a country every gulch becomes awatercourse almost before the dust is laid, the _arroyos_ turn torivers and the rivers to broad floods, drifting with trees andwreckage. But the cattlemen and sheepmen who happened to be in Bender,either to take on hands for the spring round-up or to ship supplies totheir shearing camps out on the desert, were not worrying about therailroad. Whether the bridges went out or held, the grass and browsewould shoot up like beanstalks in to-morrow's magic sunshine; and evenif the Rio Salagua blocked their passage, or the shearers' tents werebeaten into the mud, there would still be feed, and feed waseverything.

But while the rain was worth a thousand dollars a minute to thecountry at large, trade languished in the Hotel Bender. In a landwhere a gentleman cannot take a drink without urging every one withinthe sound of his voice to join in, the saloon business, while runningon an assured basis, is sure to have its dull and idle moments. Havingrung up the two dollars and a half which Jefferson Creede paid for hislast drink--the same being equivalent to one day's wages as foreman ofthe Dos S outfit--Black Tex, as Mr. Brady of the Bender bar preferredto be called, doused the glasses into a tub, turned them over to hisroustabout, and polished the cherrywood moodily. Then he drew hiseyebrows down and scowled

at the little man in the corner.

In his professional career he had encountered a great many men who didnot drink, but most of them smoked, and the others would at leasttake a cigar home to their friends. But here was a man who refused tocome in on a treat at all, and a poor, miserable excuse for a man hewas, too, without a word for any one. Mr. Brady's reflections on theperversity of tenderfeet were cut short by a cold blast of air. Thedoor swung open, letting in a smell of wet greasewood, and an old man,his hat dripping, stumbled in and stood swaying against the bar. Hisaged sombrero, blacksmithed along the ridge with copper rivets, wasset far back on a head of long gray hair which hung in heavy stringsdown his back, like an Indian's; his beard, equally long and tangled,spread out like a chest protector across his greasy shirt, and hisfiery eyes roved furtively about the room as he motioned for a drink.Black Tex set out the bottle negligently and stood waiting.

"Is that all?" he inquired pointedly, as the old man slopped out adrink.

"Well, have one yourself," returned the old-timer grudgingly. Then,realizing his breach of etiquette, he suddenly straightened up andincluded the entire barroom in a comprehensive sweep of the hand.

"Come up hyar, all of yoush," he said drunkenly. "Hev adrink--everybody--no, everybody--come up hyar, I say!" And thegraceless saloon bums dropped their cards and came trooping uptogether. A few of the more self-respecting men slipped quietly outinto the card rooms; but the studious stranger, disdaining such punysubterfuges, remained in his place, as impassive and detached asever.

"Hey, young man," exclaimed the old-timer jauntily, "step up hyar andnominate yer pizen!"

He closed his invitation with an imperative gesture, but the young mandid not obey.

"No, thank you, Uncle," he replied soberly, "I don't drink."

"Well, hev a cigar, then," returned the old man, finishing out theformula of Western hospitality, and once more Black Tex glowered downupon this guest who was always "knocking a shingle off his sign."

"Aw, cut it out, Bill," he sneered, "that young feller don't drink nersmoke, neither one--and he wouldn't have no truck with you, nohow!"

They drank, and the stranger dropped back into his reading unperturbed.Once more Black Tex scrubbed the bar and scowled at him; then,tapping peremptorily on the board with a whiskey glass, he gave way tohis just resentment.

"Hey, young feller," he said, jerking his hand arbitrarily, "come overhere. Come over here, I said--I want to talk with you!"

For a moment the man in the corner looked up in well-bred surprise;then without attempting to argue the point he arose and made his wayto the bar.

"What's the matter with you, anyway?" demanded Brady roughly. "Are youtoo good to drink with the likes of us?"

The stranger lowered his eyes before the domineering gaze of hisinquisitor and shifted his feet uneasily.

"I don't drink with anybody," he said at last. "And if you had anyother waiting-room in your hotel," he added, "I'd keep away from yourbarroom altogether. As it is, maybe you wouldn't mind leaving mealone."

At this retort, reflecting as it did upon the management, Black Texbegan to breathe heavily and sway upon his feet.

"I asked you," he roared, thumping his fist upon the bar and openingup his eyes, "whether you are too good to drink with the likes ofus--me, f'r instance--and I want to git an answer!"

He leaned far out over the bar as if listening for the first wordbefore he hit him, but the stranger did not reply immediately.Instead, with simple-minded directness he seemed to be studying on thematter. The broad grin of the card players fell to a wondering stareand every man leaned forward when, raising his sombre eyes from thefloor, the little man spoke.

"Why, yes," he said quietly, "I think I am."

"Yes, _what_?" yelled the barkeeper, astounded. "You think you'rewhat?"

"Now, say," protested the younger man. Then, apparently recognizingthe uselessness of any further evasion, he met the issue squarely.

"Well, since you crowd me to it," he cried, flaring up, "I _am_ toogood! I'm too good a man to drink when I don't want to drink--I'm toogood to accept treats when I don't stand treat! And more than that,"he added slowly and impressively, "I'm too good to help blow that oldman, or any other man, for his money!"

He rose to his utmost height as he spoke, turning to meet the glanceof every man in the room, and as he faced them, panting, his deep eyesglowed with a passion of conviction.

"If that is too good for this town," he said, "I'll get out of it, butI won't drink on treats to please anybody."

The gaze of the entire assembly followed him curiously as he went backto his corner, and Black Tex was so taken aback by this unexpectedeffrontery on the part of his guest that he made no reply whatever.Then, perceiving that his business methods had been questioned, hedrew himself up and frowned darkly.

"Hoity-toity!" he sniffed with exaggerated concern. "Who th' hell isthis, now? One of them little white-ribbon boys, fresh from the East,I bet ye, travellin' for the W. P. S. Q. T. H'm-m--tech me not--ohdeah!" He hiked up his shoulders, twisted his head to a pose, andshrilled his final sarcasms in the tones of a finicky old lady; butthe stranger stuck resolutely to his reading, whereupon the blackbarkeeper went sullen and took a drink by himself.

Like many a good mixer, Mr. Brady of the Hotel Bender was often toogood a patron of his own bar, and at such times he developed a meanstreak, with symptoms of homicidal mania, which so far had kept thetown marshal guessing. Under these circumstances, and with the rumorof a killing at Fort Worth to his credit, Black Tex was accustomed tobeing humored in his moods, and it went hard with him to be calleddown in the middle of a spectacular play, and by a rank stranger, atthat. The chair-warmers of the Hotel Bender bar therefore discreetlyignored the unexpected rebuke of their chief and proceeded noisilywith their games, but the old man who had paid for the drinks was nosuch time-server. After tucking what was left of his money back intohis overalls he balanced against the bar railing for a while and thensteered straight for the dark corner.

"Young feller," he said, leaning heavily upon the table where thestranger was reading, "I'm old Bill Johnson, of Hell's Hip Pocket, andI wan'er shake hands with you!"

The young man looked up quickly and the card players stopped assuddenly in their play, for Old Man Johnson was a fighter in his cups.But at last the stranger showed signs of friendliness. As the old manfinished speaking he rose with the decorum of the drawing-room andextended his white hand cordially.

"I'm very glad to meet you, Mr. Johnson," he said. "Won't you sitdown?"

"No," protested the old man, "I do' wanner sit down--I wanner ask youa question." He reeled, and balanced himself against a chair. "Iwanner ask you," he continued, with drunken gravity, "on the squar',now, did you ever drink?"

"Why, yes, Uncle," replied the younger man, smiling at the question,"I used to take a friendly glass, once in a while--but I don't drinknow." He added the last with a finality not to be mistaken, but Mr.Johnson of Hell's Hip Pocket was not there to urge him on.

"No, no," he protested. "You're mistaken, Mister--er--Mister--"

"Hardy," put in the little man.

"Ah yes--Hardy, eh? And a dam' good name, too. I served under acaptain by that name at old Fort Grant, thirty years ago. Waal, Hardy,I like y'r face--you look honest--but I wanner ask you 'nutherquestion--why don't you drink now, then?"

Hardy laughed indulgently, and his eyes lighted up with good humor, asif entertaining drunken men was his ordinary diversion.

"Well, I'll tell you, Mr. Johnson," he said. "If I should drinkwhiskey the way you folks down here do, I'd get drunk."

"W'y sure," admitted Old Man Johnson, sinking shamelessly into achair. "I'm drunk now. But what's the difference?"

Noting the black glances of the barkeeper, Hardy sat down beside himand pitched the conversation in a lower key.

"It may be all right for you, Mr. Johnson," he continued confidentially,"and of course that's none of my business; but if I should get drunkin this town, I'

d either get into a fight and get licked, or I'dwake up the next morning broke, and nothing to show for it but a sorehead."

"That's me!" exclaimed Old Man Johnson, slamming his battered hat onthe table, "that's me, Boy, down to the ground! I came down hyar tobuy grub f'r my ranch up in Hell's Hip Pocket, but look at me now,drunk as a sheep-herder, and only six dollars to my name." He shookhis shaggy head and fell to muttering gloomily, while Hardy revertedpeacefully to his magazine.

After a long pause the old man raised his face from his arms andregarded the young man searchingly.

"Say," he said, "you never told me why you refused to drink with me awhile ago."

"Well, I'll tell you," answered Hardy, honestly, "and I'm sure you'llunderstand how it is with me. I never expect to take another drink aslong as I live in this country--not unless I get snake-bit. One drinkof this Arizona whiskey will make me foolish, and two will make medrunk, I'm that light-headed. Now, if I had taken a drink with you aminute ago I'd be considered a cheap sport if I didn't treat back,wouldn't I? And then I'd be drunk. Yes, that's a fact. So I have tocut it out altogether. I like you just as well, you understand, andall these other gentlemen, but I just naturally can't do it."

"Oh, hell," protested the old man, "that's all right. Don't apologize,Boy, whatever you do. D'yer know what I came over hyar fer?" he askedsuddenly reaching out a crabbed hand. "Well, I'll tell ye. I've be'nlookin' f'r years f'r a white man that I c'd swear off to. Not one ofthese pink-gilled preachers but a man that would shake hands with meon the squar' and hold me to it. Now, Boy, I like you--will you shakehands on that?"

"Sure," responded the young man soberly. "But I tell you, Uncle," headded deprecatingly, "I just came into town to-day and I'm likely togo out again to-morrow. Don't you think you could kind of look afteryourself while I'm gone? I've seen a lot of this swearing-off businessalready, and it don't seem to amount to much anyhow unless the fellowthat swears off is willing to do all the hard work himself."

There was still a suggestion of banter in his words, but the old manwas too serious to notice it.

"Never mind, boy," he said solemnly, "I can do all the work, but Ijist had to have an honest man to swear off to."

He rose heavily to his feet, adjusted his copper-riveted hatlaboriously, and drifted slowly out the door. And with another spendergone the Hotel Bender lapsed into a sleepy quietude. The rain hammeredfitfully on the roof; the card players droned out their bids and bets;and Black Tex, mechanically polishing his bar, alternated successivejolts of whiskey with ill-favored glances into the retired cornerwhere Mr. Hardy, supposedly of the W. P. S. Q. T., was studiouslyperusing a straw-colored Eastern magazine. Then, as if to lighten thegloom, the sun flashed out suddenly, and before the shadow of thescudding clouds had dimmed its glory a shrill whistle from down thetrack announced the belated approach of the west-bound train.Immediately the chairs began to scrape; the stud-poker players cut forthe stakes and quit; coon-can was called off, and by the time NumberNine slowed down for the station the entire floating population ofBender was lined up to see her come in.

Rising head and shoulders above the crowd and well in front stoodJefferson Creede, the foreman of the Dos S; and as a portly gentlemanin an unseasonable linen duster dropped off the Pullman he advanced,waving his hand largely.

"Hullo, Judge!" he exclaimed, grinning jovially. "I was afraid you'dbogged down into a washout somewhere!"

"Not at all, Jeff, not at all," responded the old gentleman, shakinghands warmly. "Say, this is great, isn't it?" He turned his genialsmile upon the clouds and the flooded streets for a moment and thenhurried over toward the hotel.

"Well, how are things going up on the range?" he inquired, plungingheadlong into business and talking without a stop. "Nicely, nicely, Idon't doubt. I tell you, Mr. Creede, that ranch has marvellouspossibilities--marvellous! All it needs is a little patience, a littlediplomacy, you understand--_and holding on_, until we can pass thisforestry legislation. Yes, sir, while the present situation may seem alittle strained--and I don't doubt you are having a hard time--at thesame time, if we can only get along with these sheepmen--appeal totheir better nature, you understand--until we get some protection atlaw, I am convinced that we can succeed yet. I want to have a longtalk with you on this subject, Jeff--man to man, you understand, andbetween friends--but I hope you will reconsider your resolution toresign, because that would just about finish us off. It isn't a matterof money, is it, Jefferson? For while, of course, we are not making afortune--"

He paused and glanced up at his foreman's face, which was growing moresullen every minute with restrained impatience.

"Well, speak out, Jeff," he said resignedly. "What is it?"

"You know dam' well what it is," burst out the tall cowboy petulantly."It's them sheepmen. And I want to tell you right now that no moneycan hire me to run that ranch another year, not if I've got to smileand be nice to those sons of--well, you know what kind of sons Imean--that dog-faced Jasper Swope, for instance."

He spat vehemently at the mention of the name and led the way to acard room in the rear of the barroom.

"Of course I'll work your cattle for you," he conceded, as he enteredthe booth, "but if you want them sheepmen handled diplomatically you'dbetter send up a diplomat. I'm that wore out I can't talk to 'emexcept over the top of a six-shooter."

The deprecating protestations of the judge were drowned by the scuffleof feet as the hangers-on and guests of the hotel tramped in, and inthe round of drinks that followed his presence was half forgotten. Notbeing a drinking man himself, and therefore not given to the generouspractice of treating, the arrival of Judge Ware, lately retired fromthe bench and now absentee owner of the Dos S Ranch, did not createmuch of a furore in Bender. All Black Tex and the bunch knew was thathe was holding a conference with Jefferson Creede, and that if Jeffwas pleased with the outcome of the interview he would treat, but ifnot he would probably retire to the corral and watch his horse eathay, openly declaring that Bender was the most God-forsaken hell-holenorth of the Mexican line--for Creede was a man of moods.

In the lull which followed the first treat, the ingratiating drummerwho had set up the drinks, charging the same to his expense account,leaned against the bar and attempted to engage the barkeeper inconversation, asking leading questions about business in general andMr. Einstein of the New York Store in particular; but Black Tex, inspite of his position, was uncommunicative. Immediately after thearrival of the train the little man who had called him down hadreturned to the barroom and immersed himself in those wearisomemagazines which a lunger had left about the place, and, far from beingimpressed with his sinister expression, had ignored his unfriendlyglances entirely. More than that, he had deserted his dark corner andseated himself on a bench by the window from which he now looked outupon the storm with a brooding preoccupation as sincere as it wasmaddening. His large deer eyes were fixed upon the distance, and hismanner was that of a man who studies deeply upon some abstruseproblem; of a man with a past, perhaps, such as often came to thoseparts, crossed in love, or hiding out from his folks.

Black Tex dismissed the drummer with an impatient gesture and waspondering solemnly upon his grievances when a big, square-jowled catrushed out from behind the bar and set up a hoarse, raucous mewing.

"Ah, shet up!" growled Brady, throwing him away with his foot; but asthe cat's demands became more and more insistent the barkeeper was atlast constrained to take some notice.

"What's bitin' you?" he demanded, peering into the semi-darknessbehind the bar; and as the cat, thus encouraged, plunged recklessly inamong a lot of empty bottles, he promptly threw him out and fished upa mouse trap, from the cage of which a slender tail was wrigglingfrantically.

"Aha!" he exclaimed, advancing triumphantly into the middle of thefloor. "Look, boys, here's where we have some fun with Tom!" And asthe card players turned down their hands to watch the sport, the oldcat, scenting his prey, rose up on his hind legs and clutched at thecage, yelling.

Gr

abbing him roughly by the scruff of the neck Black Tex suddenlythrew him away and opened the trap, but the frightened mouse, unawareof his opportunity, remained huddled up in the corner.

"Come out of that," grunted the barkeeper, shaking the cage while withhis free hand he grappled the cat, and before he could let go his holdthe mouse was halfway across the room, heading for the bench whereHardy sat.

"Ketch 'im!" roared Brady, hurling the eager cat after it, and just asthe mouse was darting down a hole Tom pinned it to the floor with hisclaws.

"What'd I tell ye?" cried the barkeeper, swaggering. "That cat willketch 'em every time. Look at that now, will you?"

With dainty paws arched playfully, the cat pitched the mouse into theair and sprang upon it like lightning as it darted away. Then mumblingit with a nicely calculated bite, he bore it to the middle of thefloor and laid it down, uninjured.

"Ain't he hell, though?" inquired Tex, rolling his eyes upon thespectators. The cat reached out cautiously and stirred it up with hispaw; and once more, as his victim dashed for its hole, he caught itin full flight. But now the little mouse, its hair all wet andrumpled, crouched dumbly between the feet of its captor and would notrun. Again and again the cat stirred it up, sniffing suspiciously tomake sure it was not dead; then in a last effort to tempt it hedeliberately lay over on his back and rolled, purring and closinghis eyes luxuriously, until, despite its hurts, the mouse once moretook to flight. Apparently unheeding, the cat lay inert, followingits wobbly course with half-shut eyes--then, lithe as a panther,he leaped up and took after it. There was a rush and a scrambleagainst the wall, but just as he struck out his barbed claw a handclosed over the mouse and the little man on the bench whisked itdexterously away.

Instantly the black cat leaped into the air, clamoring for his prey,and with a roar like a mountain bull Black Tex rushed out tointercede.

"Put down that mouse, you freak!" he bellowed, charging across theroom. "Put 'im down, I say, or I'll break you in two!" He launched hisheavy fist as he spoke, but the little man ducked it neatly and,stepping behind a table, stood at bay, still holding the mouse.

"Put 'im _down_, I tell you!" shouted the barkeeper, panting withvexation. "What--you won't, eh? Well, I'll learn you!" And with awicked oath he drew his revolver and levelled it across the table.

"Put--down--that--mouse!" he said slowly and distinctly, but Hardyonly shook his head. Every man in the room held his breath for thereport; the poker players behind fell over tables and chairs to getout of range; and still they stood there, the barkeeper purple, thelittle man very pale, glaring at one another along the top of thebarrel. In the hollow of his hand Hardy held the mouse, which tottereddrunkenly; while the cat, still clamoring for his prize, raced aboutunder the table, bewildered.

"Hurry up, now," said the barkeeper warningly, "I'll give you five.One--come on, now--two--"

At the first count the old defiance leaped back into Hardy's eyes andhe held the mouse to his bosom as a mother might shield her child; atthe second he glanced down at it, a poor crushed thing trembling aswith an ague from its wounds; then, smoothing it gently with his hand,he pinched its life out suddenly and dropped it on the floor.

Instantly the cat pounced upon it, nosing the body eagerly, and BlackTex burst into a storm of oaths.

"Well, dam' your heart," he yelled, raising his pistol in the airas if about to throw the muzzle against his breast and fire."What--in--hell--do you mean?"

Baffled and evaded in every play the evil-eyed barkeeper suddenlysensed a conspiracy to show him up, and instantly the realization ofhis humiliation made him dangerous.

"Perhaps you figure on makin' a monkey out of me!" he suggested,hissing snakelike through his teeth; but Hardy made no answerwhatever.

"Well, _say_ something, can't you?" snapped the badman, hisoverwrought nerves jangled by the delay. "What d'ye mean byinterferin' with my cat?"

For a minute the stranger regarded him intently, his sad, far-seeingeyes absolutely devoid of evil intent, yet baffling in theirinscrutable reserve--then he closed his lips again resolutely, as ifdenying expression to some secret that lay close to his heart, turningit with undue vehemence to the cause of those who suffer and cannotescape.

"Well, f'r Gawd's sake," exclaimed Black Tex at last, lowering his gunin a pet, "don't I git _no_ satisfaction--what's your _i_-dee?"

"There's too much of this cat-and-mouse business going on," answeredthe little man quietly, "and I don't like it."

"Oh, you don't, eh?" echoed the barkeeper sarcastically; "well, excuse_me_! I didn't know that." And with a bow of exaggerated politeness heretired to his place.

"The drinks are on the house," he announced, jauntily strewing theglasses along the bar. "Won't drink, eh? All right. But lemme tellyou, pardner," he added, wagging his head impressively, "you're goin'to git hurt some day."