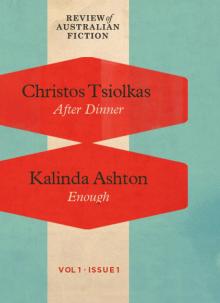

Review of Australian Fiction, Volume 1, Issue 1

Christos Tsiolkas

Volume 1: Issue 1

Christos Tsiolkas and Kalinda Ashton

Published by Review of Australian Fiction

“After Dinner” Copyright © 2012 by Christos Tsiolkas

“Enough” Copyright © 2012 by Kalinda Ashton

www.reviewofaustralianfiction.com

Editorial

Fiction is always risky. And not just the logistics of writing, publishing, and reading fiction, making a living off of it, or buying it. But also because the very nature of fiction itself – or of good fiction anyway – is to take risks, with the way you think about things, with the way you imagine yourself and the world.

This is the first issue of the Review of Australian Fiction. The first volume – of six issues, twelve stories – is already squared away. But if this little experiment is to have a life beyond the next three months depends on two things.

The first thing it depends upon is established Australian authors taking a risk and penning a new story for us. As we only pay on a royalty basis, this means that authors need to be confident enough in their own talent that their wares will attract enough readers to make their effort worthwhile. This is why we are particularly pleased with the six established Australian authors who have agreed to contribute to this first volume (and to those who have already voiced an interest in future volumes), as well as the six emerging writers who have followed their lead.

In this first issue, we have Christos Tsiolkas, fresh from the recent rollercoaster ride that accompanied the publication of his last novel, The Slap (2008), and the recent ABC television adaption. The Slap is his fourth novel. He has already completed a draft of his next novel, and we are very pleased he took the time to write the story, “After Dinner”, for this issue. Everything Tsiolkas writes crackles with risk, and this story is no exception.

The second thing that the success of the Review of Australian Fiction depends upon is readers.

Yes, the work itself is important, but it remains only a work in transit until it finds a reader to complete it, to share the risk. The Review of Australian Fiction only hopes to provide an environment where the work of author’s and their potential readers can meet. But it is up to authors and readers to take advantage of this opportunity.

This is why we have tried to keep the cover charge low, to encourage the most readers to enter; but also why most of that cover charge goes directly to the authors whose work readers have come to encounter.

It is a balancing act between logistical necessity and idealism.

Of course, authors are readers, too. It is an obvious point, but one often overlooked. It is the common ground upon which authors and their readers share. (Of course, their readers are not just their readers.) And it is in their capacity as readers also that we have asked each of our established authors to choose an emerging Australian author to be paired with, someone whose work they have read, and which they think is deserving of a wider, shared audience.

In this issue, Christos Tsiolkas has chosen Kalinda Ashton, whose debut novel, The Danger Game (2009), was published to much acclaim from Melbourne-based publisher, Sleepers. It is our hope that readers, who come here to read Tsiolkas, will go away reading Ashton. Or that those who come to read Tsiolkas, on the strength of reading The Slap, will, if they have not already, go back and read Loaded (1995) and The Jesus Man (1999) and Dead Europe (2005), his earlier novels – as well as The Danger Game by Kalinda Ashton.

Enjoy.

After Dinner

Christos Tsiolkas

– Jesus F. Christ, I wanted to smack that bitch.

Cleo indicated, overtook a car, then slid back to the left lane of the freeway. She placed her hand on Angela’s arm, squeezed it softly.

– Yes, I think we all sensed you and Erina didn’t get along.

– That obvious, was it?

– Mmmm ‘fraid so, said Cleo.

* * *

Walking up the drive, while she waited for Cleo to find they keys, Angela couldn’t stop picking apart the dinner party.

– Two hours, I couldn’t believe it, she just sat there for two hours complaining about every thing in this country. The schools, the people, the politics, the nightlife. She was even whinging about the weather. Amanda cruelly mimicked Erina’s precise but heavily accented English. And it is too too too hot, I do not like this overbearing heat, it is not pleasant. Angela’s tongue snapped harshly on the last word.

– That’s when I wanted to smack her one.

Cleo set her bag and placed a platter of food covered in foil on the kitchen bench. She called out to Felix and Titian, received no answer.

– Give me a second, I’m just going to check on the kids.

* * *

Felix was sitting against the end of his bed, playing a video game, his eyes not shifting from the kaleidoscope of action unfurling on the screen. But he sat the game control on his lap and raised his arms for a hug from Cleo. She embraced him; the sting of his doughy boy’s smell tickled her nose. It was astonishing that at fourteen he still craved her embrace; she had assumed that with the onset of adolescence he’d begrudge her open shows of affection. But, thankfully, that hadn’t happened.

– Jana’s prepared a plate of leftovers.

– Yeah, yeah, he muttered, his attention back on the game. But just as she was shutting the door he called out, What is it?

– There’s some roast lamb, some potatoes and roast capsicum. And some halva for dessert.

– Cool, he muttered, Just let me get to the next stage.

* * *

Their eldest, Titian, was sitting cross-legged on her bed, typing away on her laptop.

– There are some leftovers from the dinner.

– Not hungry.

– Jana packed in some halva, as well.

Titian screwed up her face.

– Yuck, I hate that shit. It makes my teeth hurt.

Cleo watched her daughter defiantly tap at the keys, heard a whistling sound as a message was sent off into the ether. Titian finally looked up, smiling.

– How was dinner?

Cleo cocked an eyebrow, sat on the edge of the bed.

– Good food, but your Mum got into an argument.

– What about?

– There was a couple there, he was Spanish and she was Iranian, they kept complaining about how backwards Australia is. It pissed Angela off.

– Really? Titian was disbelieving. But Angela is always dissing Australians?

– I know, I know, but they did go on a bit, and you know what Jana is like, she was joining in, agreeing with everything they said.

Titian shrugged her lean bony shoulders.

– Why don’t they go back to Spain? Or Iran? Or wherever?

– Money, I guess. They’ve got work here, their kids are at school here.

– Right. Titian’s attention was back on the computer screen. So they want all the benefits of suburban life but none of the drawbacks.

Cleo laughed out loud, leaned across and kissed Titian’s knee. Her daughter squealed, drew in her legs.

– Don’t, Mum!

– Sorry, sorry, I’m just so impressed with how smart you are.

– You’re easily impressed.

Titian had resumed typing. Cleo reclined back on the bed, closed her eyes. She could go to sleep here, she was pleasantly tipsy, it would be so lovely to just fall asleep, not bother brushing her teeth, no flossing, no undressing, just close her eyes and drift off.

– Mum!

Cleo’s eyes snapped open.

– What?

– Privacy, please.

* * *

Angela had po

ured a whiskey for herself, was sitting on the verandah rolling a cigarette.

Cleo pulled up a chair and sat next to her, placed her head on her lover’s shoulder. The sound of the ocean surf mingled with the traffic noise off the highway.

– Titian thinks if they don’t like it here they should go back to Spain. Angela snorted, sipped at her whiskey and wiped her mouth.

– I wish they would but I expect she’d be whining over there as well. She’s that type.

Cleo stopped herself from answering. She hadn’t minded the woman, she was intelligent, certainly not a fool. And her criticisms had merit. Australia was parochial, Australians were arrogant in their ignorance.

– She was very beautiful, very stylish.

– Yeah, I guess. She had thin lips.

Cleo couldn’t help it, she burst out laughing.

– My God, you really hated her, didn’t you?

– I’m just tired, listening to three people moan and criticise our lives, not being able to get drunk because I had an hour’s drive ahead of me. It wasn’t a fun evening.

Cleo took Angela’s hand, pumped it, and squeezed it.

– Thanks for being designated driver.

– ‘S okay.

Angela had removed her hand, lit her cigarette.

– It didn’t bother you?

Cleo’s eyes were shut, she was drifting off.

– Cleo?

– What?

– It didn’t bother you, all their bagging of our lives?

She was too tired for this, she didn’t want an argument. Cleo warily watched her lover raise the glass to her lips. It was nearly empty, she knew that Angela wouldn’t stop at one tonight, she was too wound up.

– You’re taking it too personally, they weren’t talking about us, they were talking about the culture generally. The way we talk about it. I’ve heard you say the same exact things on occasion.

– That’s bullshit. Angela hurled the expletive. I’m critical, not dismissive and rude. Imagine if I had gone on like that when we were in Barcelona, complaining to Aliki and Enric that the Catalans were all self-absorbed and mean-spirited. Enric would have been pissed off and he would have every right to be. It’s rude and she’s just a bitch.

Angela got up, shook her empty glass.

– I’m getting a refill. You want one?

Cleo calculated how much she already had to drink. Three glasses of wine at dinner. If she were to have a glass of spirits now she’d wake up in the middle of the night, she’d be overheating.

– I’m fine.

– Suit yourself.

How did she manage it, thought Cleo to herself, How was it that every time Angela got wound up her every utterance seemed a challenge: she was spoiling for a fight.

She closed her eyes again and listened to the sound of the waves. She could hear Felix chatting in the kitchen. He said something that made his mother laugh.

Angela returned with a fuller glass than last time. She relit her cigarette.

– Christ, that boy eats fast. He just gobbled up all that food in seconds. It’s like watching a dog eat.

– Did he leave something for Titian?

– He said she wasn’t hungry.

– So he ate everything on that giant plate?

– Yep. Angela lowered her voice. I guess all that masturbating requires a lot of energy.

Cleo started tittering. It was a secret joke between them, the endless soiled handkerchiefs and jocks in Felix’s washing, the twenty-minute showers in the morning and after soccer-practice. Of course, they wouldn’t ever humiliate their son by mocking him about it, they had once sharply warned Titian against teasing him; but it was one more proof, if more evidence were needed, about the immutable differences between boys and girls. Bearing children, raising a daughter and a son, it had all completely vanquished the social determinism she had espoused in her youth. Cleo now thought herself a closet biological essentialist.

– What are you laughing about? Felix had come out onto the verandah, munching on halva. He sat cross-legged on the slats, pieces of moist cake falling on his lap.

– Nothing, said Angela, We were discussing some wankers at the dinner. That set Cleo off on another bout of chortling.

– Yeah? Felix was eyeing them both suspiciously. He stuffed the last of the halva in his mouth. Can I have a beer, he mumbled, his mouth full.

Cleo stopped laughing, her shoulders, her neck had tensed.

– Have you had one already tonight?

Felix shook his head at Angela’s question, he was looking expectantly at her.

The little brat, thought Cleo, He’s not going to meet my eye.

– Yeah, go ahead.

– Score! Felix had shot to his feet, his action as fast and as elegant as the leap of a cat. Thanks Mum.

– You know I don’t want to encourage his drinking, Cleo said when Felix was safely back inside.

– Come on, Cleo, it’s Saturday night. You know he smokes weed, at least he’s up front with us.

– I think he’s too young.

– Stop being such a fucking nanny.

Her neck was now aching. God, how Cleo detested that word. Nanny, that had become Angela’s principal insult over the last few years. She was always moaning about the damn nanny state this, the bloody nanny state that. Cleo took in a sharp breath. She wouldn’t respond, she wouldn’t let Angela have her argument. She should just get up and go to bed now. Let her get drunk on her own, fall asleep in front of the television. She’d awake in the morning sheepish and ashamed.

She was so fucking transparent.

– I’m off to bed.

– You know what I find the hardest thing to understand, is how you could just sit there, agreeing with everything they said. It was pathetic.

That did it. The pain in her neck was giving her a headache, as was Angela’s spite. She wasn’t going to be able to fall asleep now. They were going to have a fight. Angela was going to get her way.

– Exactly what points did you want me to challenge them on? That Australians are racist and materialistic? Check. That our politicians are uninspiring? Check. That our media is a joke? Check that one as well.

Cleo had to stand, she couldn’t sit down, couldn’t bear to be sitting anywhere near Angela at this moment.

– Bloody hell, Angie, they’re migrants. Like my parents. Like yourself. You know how hard it is to be away from home, you know how much you miss England. And you know how my Dad never stops going on about how useless Australians are, it’s his number one topic of conversation. Angela didn’t respond, she was rocking back and forth on her chair. When she finally answered, her remarks were remarkably quiet, the remorseless anger seemed to have subsided.

– I miss me Mum, I miss me mates. Yeah, I do miss home but not enough to ever go back. I love my life here, I love you and the kids, I love that we can live down the road from the beach, that we can jump in the car and in an hour or two be as far away from the world as we want.

Angela swilled her whiskey, rose to get more; she started sliding open the screen door, then stopped.

– And you know that your old man feels the same way too. What did he say when he came back from Greece last time, remember? That they are more selfish than we are over there, that they’re more racist.

Her fury was returning, Angela was almost shaking as she spat out her next words.

– Your Dad and your Mum have earned the fucking right to call Australians whatever they like. They worked like dogs when they came here and they sometimes got treated like dogs. They can say whatever they like. That bitch doesn’t have the right. She’s pissed off that Melbourne isn’t Paris because in her fucked-up head she thinks she should be swanning around in an apartment off the Bastille. Those types never imagine living at the end of the Metro line, do they? Those types make me sick.

The screen door slammed.

Those types. Of course, this was what it was all about. Erina’s very job, a curator at a galle

ry, Marco was an academic at a University: that’s why Angie couldn’t stand them.

On returning, Angela almost stumbled over her chair, fell clumsily into it, the weight of her forcing the legs to scratch against the wood with a grating squeal. She was already drunk. Annoyed, Cleo turned away and rested her arms across the verandah banister. She felt the breeze on her face: salty, sour, smelling of seaweed.

She wished she could just scream it out, just talk it out, the frustration and fear she experienced every time Angela expressed her contempt for the privileges that came from a university past. Not that it was ever communicated directly, Cleo supposed that Angela herself was unaware of how effectively she had belittled and silenced that part of Cleo’s history. It was years now that she had seen many of her old friends, people she had thought of as family. They had been family. Even the move to the peninsula – though she loved it, she did, and the kids loved it, just being able to get up in the morning, run barefoot across the road and straight onto the beach; she did love it – meant that going to the movies was rare, dinners were rare, conversation and argument, like tonight at Jana’s, that was rare. Cleo had been looking forward to it for weeks, catching up, talking about new books and new films.

Bloody crime novels and Friday night after-work drinks with the Sandringham Line dykes, that’s all Angie wants, she thought spitefully to herself, nursing her bitterness, her resentment at the night ending so badly. I’m sick of crime novels and I’m sick of Frankston dykes.

– I’m getting the silent treatment, am I?

Oh go fuck yourself.

Cleo forced a smile, swung around.

– I was just enjoying listening to the ocean. It’s such a lovely balmy night.

Angela eyes fluttered, she made a fan of her hand and flicked it theatrically under her chin.

– I do not like this overbearing heat. It is not pleasant.

Cleo’s smile this time was genuine. Angie was a perfect mimic, capturing something of the flute-like tone of the woman’s voice.