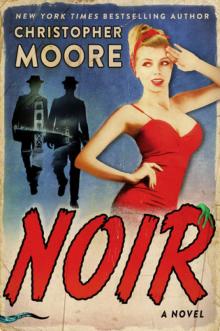

Noir

Christopher Moore

Dedication

This book is for Jeff Mong, my friend.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Note

Prologue

1: Sammy and the Cheese

2: Tall House of Happy Snake and Noodle

3: The Kid

4: Dinner in North Beach

5: Dames, They Come and Go

6: A Sweet Disaster

7: The Tenderloin Ain’t Just a Piece of Meat

8: A Receipt for Pookie

9: Laff in the Dark

10: Surprise

11: How to Ice a Guy

12: Paying Mao

13: Rats

14: Jukin’ to Jimmy’s

15: Let’s Say, Tax Guys

16: This and That, Now and Then, Here and There

17: The Road to Lone’s

18: Dark Town

19: Sampling Social Clubs of San Francisco

20: The Name of the Snake

21: The Moonman

22: Nonplussed

23: The Cheese Holds Sway

24: Two P-Phooms

25: There Will Be Donuts

26: The Nob

27: Sometimes

Afterword

About the Author

Also by Christopher Moore

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

This story is set in 1947 America. The language and attitudes of the narrators and characters regarding race, culture, and gender are contemporary to that time and may be disturbing to some. Characters and events are fictional.

Prologue

I did not scream when I came in the back door of Sal’s Saloon, where I work, to find Sal himself lying there on the floor of the stockroom, the color of blue ruin, fluids leaking from his various holes and puddling on the ground, including a little spot of blood by his head. Now, I am the younger brother of an older brother who often measured the worth of a guy by his ability to not scream under pressure, and insisted, in fact, that if any screamlike sounds ever reached Ma and/or Pa, this younger brother, me, would receive a pasting such as I had never known, including severe and painful Indian burns to the bone—a threat my older brother, Judges, may he rest in peace, backed up with great enthusiasm through most of my boyhood.

So, first I closed the back door, made sure it was solidly latched, then I glanced through the doorway into the front of the bar, which was still dark, and only then did I scream. Not the scream of a startled little girl, mind you, but a manly scream: the scream of a fellow who has caught his enormous dong in a revolving door while charging in to save a baby that was on fire or something.

So when I was finished screaming, I looked around and spotted the big wooden crate in the middle of the stockroom with big black letters stenciled upon it reading DANGER! LIVE REPTILE!

The crate was open, some kind of straw that had been in it scattered around, and then I saw the torn envelope and the letter lying by Sal’s dead hand. It was from Bokker, the South African merchant marine, to me, and I realized what the crate had held. I gave Sal’s stiff a quick once-over, and yeah, there were two puncture wounds on his neck, swollen like boils, marks of smaller teeth in a crescent shape below that.

Full-blown electric jitters ran up my spine and I froze, holding the letter like I just got a telegram informing me I had just been violently croaked. Stop. I didn’t know, exactly, what a black mamba looked like, but from what the South African had told me, they were large and dark and very fast, so I was pretty sure there was not one between me and the two feet to the back door, but there definitely might have been one still in the saloon somewhere.

I should have called someone. I needed to call someone. Not the police, I thought, since they might be looking for me regarding kidnapping one of their own, and also, since Sal took the big nap by way of a snake I bought and paid for, and as I had miles of motive, there might be some suspicion. So, no. I could have called my folks, I supposed, even though I hadn’t called them since I left Boise. “Oh, hi, Ma, I know you haven’t heard from me in years, but I got a little problem—” Nah.

So I thought, hey, the phone is all the way inside the saloon, on the wall behind the bar—the bar—where a giant, deadly snake could be napping, and then I thought, perhaps a pay phone. Perhaps, I thought, I should go see my business partner, Eddie Moo Shoes, and discuss the dilemma in which I found myself, and while at it, inform him that he was my business partner in a venture that seemed to have gone somewhat pear-shaped.

I took a deep breath and held it while I dug into Sal’s pocket for his keys, found them, then stepped politely over him and out the back door, scooting his leg away a little as I went, so it would be easier to get back in. Once outside in the alley, I locked the door, and sighed as if I’d stepped safely off a minefield. But when I turned around there were two tall, thin guys in black suits, hats, and sunglasses, standing there behind me—and I mean right there. It’s like they’d been waiting for me. They were trying to act unflappable, but they were flapped more than somewhat by my second manly scream of the day.

There are times in a guy’s life when he finds himself floating facedown in a sea of troubles, and as hope bubbles away, he thinks, How the hell did I get here?

I mean, I didn’t know then what the two mugs in black suits knew, which was that across the vastness of space, we were being studied by intellects far superior to man’s, by beings that regarded us with envious eyes and, slowly and surely, were drawing their plans to come to our world and motorboat the bazooms of our dames.

Yeah, a dame, that’s how it starts . . .

1

Sammy and the Cheese

She had the kind of legs that kept her butt from resting on her shoes—a size-eight dame in a size-six dress and every mug in the joint was rooting for the two sizes to make a break for it as they watched her wiggle in the door and shimmy onto a barstool with her back to the door. I raised an eyebrow at the South African merchant marine who’d been spinning out tales of his weird cargo at the other end of the bar while I polished a shot glass.

“That there’s a tasty bit of trouble,” said the sailor.

“Yep,” I said, snapping my bar towel and draping it over my arm as fancy as you please. “You know what they say, though, Cap’n, full speed ahead and damn the torpedoes.” So I moved down the bar toward the dame, beaming a smile like a lighthouse full of charm, but trying to keep my limp on the Q.T. to discourage curiosity.

“I don’t think that’s what they were talking about, Sammy boy,” said the sailor, “but steam on.” Which is the kind of cheering a guy will give you when figuring it’s no skin off his nose if you get shot down.

“What can I get you, Toots?” I said to the dame. She was a blonde, the dirty kind, and her hair was pinned up on her head so it kind of shot up dark, then fountained out yellow every which way in curls at the top—which made her look a little surprised. Her lips reminded me of a valentine, shiny red and plump, but a little lopsided, like maybe she’d taken a shot to the kisser in an earlier round, or the valentine heart had acute angina. Crooked but inviting.

Then the dame fidgeted on the barstool, as if to get a better fit on her bottom, causing a gasp to go through the room that momentarily cleared the smoke, as if a truck-size dragon had sucked it out through the back door. It’s not that a lone dame never came into Sal’s; it’s just that one never came in this early, while it was still light out and the haze of hooch hadn’t settled on everyone to smooth over a doll’s rougher edges. (Light being the natural enemy of the bar broad.)

“The name’s not Toots,” said the blonde. “And give me something cheap, that goes down easy.”

There then commenced a lot of cou

ghing as all the guys in the joint were suddenly paying attention to draining drinks, lighting cigarettes, adjusting the angles of their hats and whatnot, as if the dame’s remark had not just floated like a welcome sign over a room full of hustlers, gamblers, day drunks, stevedores, sailors, ne’er-do-wells, and neighborhood wiseguys, each and every one a hound at heart. So I looked over the shotgun bar, trying to catch every eye as I was reaching down, as if I was going for my walking stick—which is my version of the indoor baseball bat most bartenders keep, and even though my cane was ten feet out of reach, they got the message. I am not a big guy, and I am known to have a slow boil, but I have quick hands and I put in an hour on a heavy bag every day—a habit I picked up due to my inability to know when to keep my trap shut, so it is known that I can handle myself. Most of those mugs had seen more than one guy poured into the gutter out front after thinking my sunny disposition and bum foot made me a pushover, so they kept it polite. Then again, I also controlled the flow of booze. Coulda been that.

“What do I call you, then, miss?” I asked the blonde, locking my baby blues on her cow browns, careful not to ogle her wares, as dames often do not care for that, even when it is evident that they have spent no little time and effort preparing their wares for ogling.

“It’s missus,” she said.

“Will the mister be joining you, then?”

“Not unless you want to wait while I go home and grab the folded flag they gave me instead of sending him back to me.” She didn’t look away when she said it, or smile. She didn’t look down to hide her grief or pretend she was pushing back a tear, just looked at me dead-on, a tough cookie.

First I thought she might be busting my chops for calling her Toots, but whether she was or wasn’t, I was thinking the best way to dodge the hit was to act like I just took a shot to the body.

“Aw, jeeze, ma’am, I’m sorry. The war?” Had to be the war. She couldn’t have been more than twenty-three or -four, just a few years younger than me, I guessed.

She nodded, then started fussing with the latch on her pocketbook.

“Put that away, it’s on the house,” I said. “Let’s start over. I’m Sammy,” I said, offering my hand to shake.

She took it. “Sammy? That’s a kid’s name.”

“Yeah, well, the neighborhood is run by a bunch of old Italian guys who think anyone under sixty is a kid, so it’s on them.”

Then she laughed, and I felt like I just hit a home run. “Hi, Sammy,” she said. “I’m Stilton.”

“Pardon? Mrs. Stilton?”

“First name Stilton. Like the cheese.”

“Like what cheese?”

“Stilton? You’ve never heard of it? It’s an English cheese.”

“Okay,” I said, relatively sure this daffy broad was making up cheeses.

So she pulled her hand back and fidgeted on the stool again, like she was building up steam, and all the mugs in the place stopped talking to watch. I just stood there, lifting one eyebrow like I do.

“My father was a soldier in the Great War. American. My mother is English—war bride. They had their first real date after the war in the village of Stilton. So, a few years later, when I was born, that’s what Pop named me. Stilton. I was supposed to be a boy.”

“Well, they totally screwed the pooch on that one,” I said, and I gave her a quick once-over, out of respect for her nonboyness. “If you don’t mind me sayin’.” Suddenly I wished I was wearing a hat so I could tip it, but then I realized that she and I were probably the only people in all of San Francisco not currently wearing hats. It was like we were naked together. So I grabbed a fedora off a mug two stools down and in a smooth motion put it on and gave it a tip. “Ma’am!” I said with a bow.

So she laughed again and said, “How about you fix me an old-fashioned before you get in any deeper, smart guy?”

“Anything for you, Toots,” I said. So I flipped the hat back to the hatless mook down the bar, thanked him, then stepped to the well and started putting together her drink.

“Don’t call me Toots.”

“C’mon, it’s better than ‘the Cheese.’”

“But ‘the Cheese’ is my name.”

“So it is,” I said, setting the drink down in front of her and giving it a swizzle with the straw. “To the Cheese. Cheers.”

Then I wanted to ask her what brought her into my saloon, where she was from, and did she live around the neighborhood, but there’s a fine line between being curious and being a creep, so I left her with the drink and made my way back down the bar, refilling drinks and pulling empties until I got back to the South African merchant marine.

“Looks like you charmed her, all right,” said the sailor. “What’s she doing here, by herself, in the middle of the afternoon? Hooker?”

“Don’t think so. Widow. Lost her old man in the war.”

“Damn shame. Lot of those about. Thought I was going to leave my wife a widow a hundred times during the war. Worked a Liberty ship running supplies across the Atlantic for most of it. I still get nightmares about German U-boats—” The sailor stopped himself in the middle of the tale and shot a glance at my cane, leaning on the back bar by the register. “But I guess I was luckier than most.”

So after feeling top of the world over making the blonde laugh, I felt like a four-star phony all of a sudden, which happens like that, but I shook it off and gave the sailor a punch in the shoulder, letting him off the hook. “Doesn’t sound that lucky,” I said, “considering your cargo.”

“Like Noah’s bloody ark,” he said. “That’s what it is. You haven’t sailed until you’ve sailed through a storm with a seasick elephant on board. Had a stall built for him in the hold. Poor bloke that has to muck it out will be at it for days. We offloaded the animal in San Diego last week, but the stink still lingers.”

“Any tigers?” I asked.

“Just African animals. Tigers are from Asia.”

“I knew that,” I said. I probably should have known that. “Never seen a tiger.”

“The big cats don’t bother me much. They’re in iron cages and you can see what you got, stay away from them. Push a bit of meat into the cage every few days with a long stick. A very long stick. It’s the bloody snakes that give me the jitters. Next week our sister ship is bringing in a cargo of every deadly bloody viper on the Dark Continent, going to a lab at Stanford. Snakes don’t need to eat, so they’re just in wooden crates. You can’t even see them. But if one of them was to get loose, you’d never know until it bit you.”

“Like a U-boat?”

“Exactly. There’ll be a dozen black mambas on board. Those buggers grow ten, fifteen feet long. Saw one of them go after a bloke once when I was a kid. Mambas don’t run away like a proper snake. They stand up and charge after you—faster than you can run. Poor bastard was dead in minutes. Foaming at the mouth and twitching in the dirt.”

“Sounds rough,” I said. “That settles it. I am never, ever going to Africa.”

“It’s not all bad. You should come over to the dock in Oakland in the morning and see the rest of the menagerie before we offload. I’ll give you the grand tour. Ever seen an aardvark? Goofy bloody creatures. Will try to burrow through the steel hull. We got two aardvarks.”

“Aardvarks are delicious,” said Eddie Shu, because that’s the kind of thing he says, trying to shock people, because it is a well-known fact that Chinese guys eat some crazy shit. Eddie is a thin Chinese guy wearing a very shiny suit and black-and-white wingtips. His hair was curled up and lacquered back to look like Frank Sinatra’s. I didn’t see him come in because I was trying to keep an eye on the blonde, so I figure he snuck in the back door, which no one is supposed to do, but Eddie is a friend, so what are you gonna do?

“Pay no attention to this mope,” I said to the sailor. “He lies like an Oriental rug.”

“Fine,” said Eddie. “But as the Buddha says, ‘A man who has not tasted five-spice aardvark has never tasted joy.’”

“Uh-huh,” I said. “The Buddha says that, huh?”

“Far as you know.”

“Eddie Moo Shoes, this is Captain . . .” And here I paused to let the sailor fill in the details.

“Bokker,” said the South African. “Not a captain, though. First mate on the Beltane, freighter out of Cape Town.”

So Moo Shoes and the mate exchanged nods, and I said, “Eddie works at Club Shanghai down the street.”

“Who’s the tomato?” Eddie asked, tossing his fake-Sinatra forelock toward the blonde. I found I was somewhat defensive that he called her a tomato, despite the fact that she was that plus some.

“Just came in,” I said. “Name’s Stilton.”

“Stilton?”

“Like the cheese,” I explained.

Eddie looked at me, then at the sailor, then at me. “The cheese?”

“That’s what she said.”

“Have you seen her naked?” asked Moo Shoes.

Now, in the meantime I had been watching various patrons circle and dive on the blonde, and each of them limping away, trailing smoke, shot down with a regretful but coquettish smile. And meanwhile, she kept looking up at me, like she was saying, “Are you gonna let this go on?” Felt like that’s what she was saying, anyway. Maybe every guy in the place felt that way. This Stilton broad had something . . .

“Oh yeah,” I said, answering Moo Shoes. “She walked in naked, but I had to ask her to put on some clothes so as not to distress the upstanding citizens who frequent this fine establishment on their way back and forth to Mass.”

“I’d like to see her naked,” said Moo Shoes. “You know, make sure she’s good enough for you.”

“Not for you, then?” the sailor asked Moo.

And Moo Shoes nearly went weepy on us, hung his head until his Sinatra forelock drooped on the sad. “Lois Fong,” he said.

“Dancer at the club,” I explained.

“That dame wouldn’t so much as punch me in the throat if it made me cough up gold coins.”