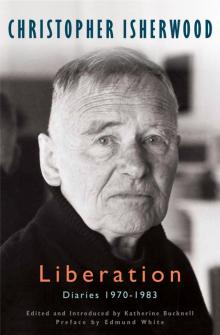

Liberation

Christopher Isherwood

LIBERATION

DIARIES, VOLUME THREE:

1970–1983

CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD

Edited and Introduced by Katherine Bucknell

Preface by Edmund White

Contents

Preface

Introduction

Textual Note

Acknowledgements

Liberation: January 1, 1970–July 4, 1983

January 1–March 2, 1970

England, March 2–April 30, 1970

May 27, 1970–August 26, 1972

September 2, 1972–December 14, 1974

January 1, 1975–December 31, 1975

Day-to-Day Diary, January 1–July 31, 1976

August 1, 1976–June 9, 1980

July 16, 1980–July 4, 1983

Glossary

Index

About the Author

Books by Christopher Isherwood

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

Readers of novels often fall into the bad habit of being overly exacting about the characters’ moral flaws. They apply to these fictional beings standards that no one they know in real life could possibly meet—nor could they themselves. They condemn a heroine, say, for not facing and condemning her lover’s ethical cowardice on some fine point of inner struggle; both her failure and his would scarcely be perceptible in real life. Sometimes it almost feels as if readers, in discussing a book, are showing off, are eager to display a refinement that no one would bother with in the heat of actual experience. In real life everyone is too busy, too submerged in the murk of getting and spending, too greedy to survive and even to prevail to be able to make much out of moral niceties. In any event, friends are always too willing to forgive lapses that they scarcely notice and if they register are sure to share and eager to pardon. Real life is so rough-and-tumble, so clamorous, a bit like an over-amplified rock band on drugs; only in the shaded purlieus of fiction do we catch the tinkling strains of moral elegance coming from another room.

I mention all this because reading the several thousand pages of Isherwood’s complete journals is an instructive corrective to the prissiness of reading fiction. Isherwood, whom most of us would consider to be nearly saintly if we knew him personally, had faults that we’d say were unforgivable in a novel (he was careful to distance himself from these very faults in his autobiographical fiction). He was seriously anti-Semitic and a year never goes by in his journals that he doesn’t attribute an enemy’s or acquaintance’s bad behaviour to his Jewishness. I suppose some people would argue that the British gentry are or at least were like that, or that he grew up in another epoch and should not be held to the standards of today. I don’t think that that defense quite works. After all, Isherwood lived in Berlin in the late 1920s and early 1930s and experienced first-hand the rise of Hitler to power and witnessed directly the appalling effect of the Nazis on the lives of his Jewish friends. Later he lived in Los Angeles for four decades and worked closely with many Jews; his milieu would never have accepted his anti-Semitism had it been declared. Moreover, he knew perfectly well that every word he wrote, even in these journals, would eventually be published, so one can’t even argue that he was simply sounding off in notes not meant for anyone else’s eyes.

Then he is a dreadful hypochondriac and in spite of all his much-vaunted spirituality terrified of the least ailment. He worries obsessively about his weight and berates himself when he’s a pound or two up on the scale, though he seldom weighs more than 150. He worries constantly (with good reason) about his drinking (“I do hate it so,” he admits).

And then he can be quite nasty about women friends and their writing. When he travels down to Essex to see Dodie Beesley he reads her novel and says, ‘It is exactly what I feared: one of those patty-paws romances, a little kiss here, a little wistful regret there, one affair is broken off, another starts up. Magazine writing. What’s wrong with it, actually? It’s so pleased with itself, so fucking smug, so snugly cunty, the art of women who are delighted with themselves, who indulge themselves and who patronize their men. They know that there is nothing, there can be nothing outside of the furry rim of their cunts and their kitchens, their children and their clubs.” Then, in a reversal typical of Isherwood, he writes, “. . . I am indulging in the luxury of being brutal about it because I know I will have to be polite about it to Dodie tomorrow—I also know that I shall want to be polite, because I do respect her and she is indeed so much wiser and subtler and better than this silly book.”

Oh, yes, he’s full of faults and yet I think any fair-minded reader who applies to Isherwood the very approximate demands of life and not the overly exacting standards of fiction will have to admit that he or she has seldom spent so much time with someone so generally admirable. To say so in no way mitigates the obnoxiousness of his real faults. But we should forgive him with the same liberality we apply to ourselves and our friends.

He loves his partner Don Bachardy with a constant devotion that is almost unparalleled in my experience. In the preceding volume, which covered the 1960s, Bachardy was endlessly quarrelsome and difficult. But in this volume, the last, which covers the final decade of Isherwood’s life, Bachardy has achieved a measure of worldly success as an artist and has escaped the confines of domesticity enough to enjoy plenty of sexual adventures—enough to catch up with all the sex Isherwood himself had enjoyed in his youth in England, Germany and America. In total contrast to the anger and spite of the 1960s, in this volume Don is endlessly playful and affectionate and kind, and Isherwood (who was thirty years older) is deliriously happy. His main regret about dying is that he must leave Don, though as a Hindu he must have imagined he’d join Don in a future life.

After he has lunch with a friend called Bob Regester who is having problems with his lover, Isherwood writes: “So of course I handed out lots of admirable advice, which I would do well to follow, myself. Don’t try to make the relationship exclusive. Try to make your part of it so special that nobody can interfere with it even if he has an affair with your lover. Remember that physical tenderness is actually more important than the sex act itself.” We learn that Chris and Don no longer have sex but that they consider their relationship to be very physical; they sleep together and they are constantly touching each other. At a certain point Chris writes, “I’m glad people have had crushes on me, glad I used to be cute; it is a very sustaining feeling.” I remember the ancient Virgil Thomson once telling me in Key West that he, too, had had a lot of sexual allure and success in his day.

We seldom count a happy marriage as a real accomplishment and yet it so clearly is—it is virtually an aesthetic achievement. It requires the same sense of proportion, creativity, empathy, patience, perseverance, equanimity and generosity of spirit as does the making of a novel or play. Isherwood’s happy marriage with a tempestuous young man is, unlike the writing of a novel, a collaborative act (in that way it’s more like preparing a play—and not incidentally Chris and Don were constantly working on film and theater scripts together). Anyone who has ever had a happy marriage knows that it is never stable, never finished; it changes every day and is always being created or at least celebrated anew. I suppose in that sense it is like cooking, something that requires a skill that can be acquired over time but that needs to be done every day from scratch. Isherwood understands the vagaries of love better than anyone and he feels (partly to Bachardy but largely to the gods) gratitude, the most appropriate of all the amorous emotions.

Another thing we admire about Isherwood is his seriousness and his curiosity. His reading lists reveal how far-flung his interests are and how deep they go. He is constantly reading demanding books that inform him about every aspect of th

e world past and present. At one moment, by no means atypical, he is reading Solzhenitsyn’s The First Circle, Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. His curiosity about the people around him is equally far-reaching. He wants to know what everyone is up to. His old friends—especially David Hockney, Hockney’s erstwhile lover Peter Schlesinger, W.H. Auden, Tony Richardson, his neighbor Jo Masselink, and of course the whole Vedanta crew starting with Swami—make nearly monthly, sometimes weekly or even daily appearances. When Isherwood travels to New York he sees the composer Virgil Thomson and when he goes to England he sees E.M. Forster and the beautiful ballet dancer Wayne Sleep (portrayed in a wonderful canvas by Hockney) and travels north to visit his strange, alcoholic brother Richard.

For me this book sometimes felt like old-home week since I know or knew Virgil and Hockney and Howard Schuman and Gloria Vanderbilt and Edward Albee and Dennis Altman and Lauren Bacall and Allen Ginsberg and Gore Vidal and Brian Bedford and Lesley Blanch and Paul Bowles and William Burroughs and Truman Capote and Aaron Copland and on and on. I never met Jim Charlton but towards the end of his life he sent me dozens of letters that were nearly incoherent. I drop all these names because I suppose I feel that I can testify that Isherwood is accurate in his depictions and almost too generous in his assessments.

We learn how important Forster was to Isherwood; at one point he even considers writing about both Swami and Forster and calling it My Two Gurus (of course what he did was to write about Swami alone in My Guru and His Disciple, a book I praised in the Sunday New York Times Book Review). He seems delighted when Forster tells him that Vanessa Bell “was much easier to get along with than her sister, and how Virginia would suddenly turn on you and attack you.” He admires Forster’s equanimity, his relationship with his policeman friend, Bob Buckingham, and Buckingham’s wife, May.

Isherwood was extremely important to me but I was just a blip on his screen as I learned reading his book. He gave me a blurb for my 1980 book States of Desire, though he told me he hadn’t liked my earlier arty fiction. In those two novels he’d seen the bad influence of Nabokov, he claimed (Lolita he’d once dismissed as the best travel book anyone had written about America). I saw him and Don in New York and again in Los Angeles and I talked to him several times on the phone (he told me that he didn’t have the patience to answer letters but that he was happy to receive telephone calls). In the years that followed I would mention in inter views that Isherwood and Nabokov were the two writers who’d had the most influence on me, just as a few years later Michel Foucault in Paris became my last mentor—in spite of himself, since he didn’t believe in being or having a mentor. Perhaps it is my fate that Nabokov, Isherwood and Foucault, the three men who had the greatest intellectual impact on me, would have had to scratch their heads to remember anything about me or even my name.

We learn so much in this book precisely because it is so detailed and daily. We hear about the earthquakes, mostly small and soon over. We learn how much Chris hates to travel. We hear about his money fears (at a certain moment he is triumphant because he has $74,000 in savings). When he asks Don how he will respond to his death, Don assures him he’ll give him a great send-off. Chris refers to himself several times as a “ham” who loves to show off in public and please crowds. We realize through a few hints that he, Chris, still has a sex life with various young and less young men.

Isherwood had spent most of his life in the closet, as anyone of his generation and social class would have, but in this volume he is relieved when an English journalist, almost in passing, refers to him directly and without hedging as a homosexual. In Kathleen and Frank, his memoir about his parents which he wrote during the period covered by this volume, he comes out in print for the first time. To be sure, he’d written frequently about homosexuals previously, notably in the groundbreaking novel A Single Man, but only now in the 1970s was he “out” in his own right, clearly and openly, without any screen of fiction between him and the reader. In the seventies he took an interest in gay politics, attended a few gay events and gave talks to gay groups. At one point he admits quite frankly that part of his original attraction to Vedanta lay in the fact that it accepted him as a homosexual.

Like any old man or woman he is surrounded by dying friends and family members. Isherwood is unusually calm and undramatic about these deaths (including that of his brother Richard), but he is never unfeeling. Perhaps because he thought so much about his own approaching death, he was able to take the death of his generation and of his elders in stride.

Even in old age Isherwood is still very much the working writer, sometimes collaborating with Bachardy (on a joint volume of texts and drawings called October, for instance), most often working alone. We learn that Bachardy had a true gift for naming things. Just as he’d thought up the title A Single Man in the sixties, now My Guru and His Disciple and Christopher and His Kind were among the titles he suggested to Isherwood. Constantly Isherwood, like any writer, is lamenting his laziness and lack of progress, but somehow or other the old nag or “Dobbin” as he calls himself plods on toward the finish line. He is also hard at work on film scripts and theatrical adaptations of his various “properties,” though he had nothing to do with Cabaret, the musical and movie that made him the most money and earned him the widest fame (nor did he much like Cabaret, though he was attracted to Michael York).

Isherwood had a personality that sparkled. When he entered a room everyone sat forward and smiled. He avoided all the accoutrements of the famous man. He asked questions and listened to answers. He refused to be complimented and if some earnest young admirer persisted, Isherwood broke into a whinny of laughter. His laugh could be deflating; once I called him from Key West to read him the end of Chateaubriand’s Mémoires d’outre-tombe in which the author seizes his cross and walks bravely down into his grave. I was in tears but Chris thought it all so absurd that he laughed uncontrollably and I was puzzled then offended then (slightly) enlightened—I could just begin to see it was all pretty silly. When my ex, Keith McDermott, played in a theatrical adaptation of one of Chris’s novels, I remember that all the Hindu monks in the play were endlessly laughing in ways a Christian divine would have considered beneath his dignity. Laughter for Chris could be deflating or just merry or impertinent—or divine, the very sound the planets make as they dance their eternal dance.

He was still startlingly handsome with his piercing eyes, shaggy eyebrows, straight nose and downturned mouth which was constantly turning up in a smile. He had a lot of charm but his charm did not stand in the way of his expressing strong opinions, especially about literature. How open writers are with one another is partly a question of nationality (the English are thick-skinned, the French thin-skinned, the Americans very thin-skinned) and generation (writers in the nineteenth century were much franker than twentieth-century writers). Isherwood came from a knock-about world of confident, upper-middle-class men and women from Oxford or Cambridge; they never minced words, any more than Martin Amis or Christopher Hitchens mince words now.

But of course he wasn’t really one of his old London crowd. He’d been a pacifist and had moved to America on the brink of World War II, which had earned him the enmity of most of his countrymen—and of some Brits even to this day. He was openly gay; sophisticated heterosexuals treat gays as if they’re a bad joke that’s gone on too long. Tiresome. A bit silly. Tiresome and juvenile. And then, worst of all, he was a Hindu. That seemed a very “period” thing to be in Britain, something out of the dubious, not quite hygienic mysteries of Madame Blavatsky, a pure product of the 1890s. In America, Hinduism was more puzzling than anything (“Why didn’t he go directly on to Zen?” most of us wondered; Hinduism seemed to Zen what Jung seemed to Freud: seedy, not very rigorous, slightly embarrassing).

He was a wonderful host, and that’s how I choose to recall him. Carefully dressed, he’d climb out of an easy chair and greet a friend warmly, show him around his house. I remember seeing a photo of the very y

oung Don with Marilyn Monroe and Chris with Joan Crawford (“our dates,” Chris emphasized). In his study he showed me a school picture of Auden and himself, something he kept close by. He mentioned Tennessee Williams (“We had an affair in the 1940s when we were both still rather presentable”). There were Hockneys to be seen and works by other artist friends and of course Don’s studio to be visited. If we drove to a nearby restaurant for dinner Chris lay down in the back seat (“I was driving Don mad with all my wincing, so if I lie down I don’t see anything or complain”). It gratified me that even if I was a very marginal player in his drama, nevertheless he accorded me all his warmth and cleverness and kindness, if only for an evening.

Edmund White

New York City

February 25, 2011

Introduction

In his novels and autobiographies, Isherwood typically traces one thread at a time—a single character or relationship, at most a milieu in cross-section over a short period. In the pages of his diaries, he weaves together, entry by entry, week by week, the surprisingly diverse areas of his life, every thread touching upon, reinforcing, and contrasting with every other thread, so that the rich cloth of his own life also portrays the fleeting sensibility of his time. The pages teem with personalities, but even as Isherwood becomes an icon of the gay liberation movement and a sought-after participant in the celebrity culture which burgeoned in the 1970s, he continues to tell us as much about his housekeeper, his doctor, the boy trimming his hedge, or his weird and reclusive brother in the north of England as he does about David Bowie or John Travolta, Elton John or Jon Voight. Isherwood was fond of a great many people. He was a practiced, self-conscious charmer who worked hard to draw others to him. Some of his acquaintances and friends have been surprised and upset by what he wrote about them in his diaries, concluding that he withheld from them in life his true opinion recorded secretly. But what he wrote in the diaires is not what he secretly thought, it is what he also thought, on the particular day when he wrote it. It is part of a complete portrait that is perhaps never even completable. To him, a human individual was comprised of many traits; he found the so-called bad traits just as interesting and sometimes more attractive than the so-called good traits. Here is what he wrote about the woman doctor he selected in his old age to see him out of the world: “She’s a nonstop talker, an egomaniac, a show-biz snob, and extremely sympathetic. Don’s in favor of her, too.”1 And he criticized nobody more harshly in his diaries than he criticized himself and his companion, the American painter Don Bachardy, whose physical glamour and creative vitality transfigured Isherwood’s last thirty-three years.