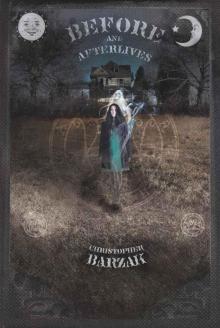

Before and Afterlives

Christopher Barzak

Before andAfterlives: Stories

Christopher Barzak

Published by Lethe Press

Maple Shade, New Jersey

Copyright © 2013 Christopher Barzak. all rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, microfilm, and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published in 2013 by Lethe Press, Inc.

118 Heritage Avenue, Maple Shade, NJ 08052 usa

lethepressbooks.com / [email protected]

isbn: 978-1-59021-369-8 / 1-59021-369-6

e-isbn: 978-1-59021-285-1 / 1-59021-285-1

Credits for previous publication appear at the end.

These stories are works of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, whether living or dead, business establishments, organizations, clubs, events, locales, services, or products is entirely coincidental.

Interior design: Alex Jeffers.

Cover art and design: Steven Andrew.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barzak, Christopher.

[Short stories. Selections]

Before and afterlives : stories / Christopher Barzak.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59021-369-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-59021-285-1 (e-book)

1. Ghost stories, American. 2. Paranormal fiction. 3. Magic--Fiction. I.

Title.

PS3602.A844B44 2013

813’.6--dc23

2012038020

Praise for Christopher Barzak and

Before and Afterlives

“Barzak’s sympathy and humor, his awareness, his easeful vernacular storytelling, are extraordinary.”

—Jonathan Lethem, author ofMotherless Brooklyn

“Throughout this collection, Barzak effectively writes people contending with their fears and doubts but most especially he writes about loneliness, and it is this writerly radar for alienation that perhaps makes him so perceptive when it comes to his teen characters. ...Barzak makes it all seem so easy, these gentle glimpses into his characters’ lives, and even though these lives might include mermaids or ghostly parents or talking fireflies, the extraordinary aspects are not what make his tales so magical. It’s the way he sees plain ordinary people that gives his stories such power; the way he sees us and yet loves us anyway. Bravo.”

—Bookslut

“Masterfully crafted...each one packs a punch.”

—Publishers Weekly

“[Barzak] treads a delicate line between the paranormal ghost romance and the more nuanced literary tradition that includes Shirley Jackson, Peter S. Beagle, and Robert Nathan...Before and Afterlives is a fine introduction to the short fiction of an author who, in a fairly short career, has established himself as one of the most distinctive voices and lyrically effective prose stylists in recent fantasy.”

—Gary K. WolfeforLocus Magazine

Also by Christopher Barzak

One for Sorrow 2007

The Love We Share Without Knowing 2008

Interfictions 2 (co-edited with Delia Sherman) 2009

Birds and Birthdays 2012

For Tony Romandetti

Before, After, Always

Contents

What We Know About the Lost Families of — House

The Drowned Mermaid

Dead Boy Found

A Mad Tea Party

Born on the Edge of an Adjective

The Other Angelas

A Resurrection Artist

The Boy Who Was Born Wrapped in Barbed Wire

Map of Seventeen

Dead Letters

Plenty

The Ghost Hunter’s Beautiful Daughter

Caryatids

A Beginner’s Guide to Survival Before, During, and After the Apocalypse

Smoke City

Vanishing Point

The Language of Moths

Publication History

Acknowledgements

About the Author

What We Know About

the Lost Families of — House

But is the house truly haunted?

Of course the house is haunted. If a door is closed on the first floor, another on the second floor will squeal open out of contrariness. If wine is spilled on the living room carpet and scrubbed at furiously and quickly so that a stain does not set, another stain, possibly darker, will appear somewhere else in the house. A favorite room in which malevolence quietly happens is the bathroom. Many speculate as to why this room draws so much attention. One might think that in a bathroom things would be more carefree, in a room where the most private of acts are committed, that any damned inhabitants could let down their hair or allow a tired sigh to pass through their doomed lips.

Perhaps this is exactly what they are doing in the bathroom, and we have misunderstood them. They turn on the shower and write names in the steam gathered on the mirror (never their own names, of course). They tip perfume bottles over, squeeze the last of the toothpaste out of its tube, they leave curls of red hair in the sink. And no one who lives in the house—no one living, that is—has red hair, or even auburn. What’s worse is when they leave the toilet seat up. They’ll flush the toilet over and over, entranced by the sound of the water being sucked out. This is what these restless inhabitants are endlessly committing: private acts.

The latest victims

Always there has been a family subject to the house’s torture. For sixty-five years it was the Addlesons. Before that it was owned by the Oliver family. No one in town can remember who lived in the house before the Olivers, not even our oldest residents. We have stories, of course, recountings of the family who built — House, but their name has been lost to history. If anyone is curious, of course there is the library with town records ready to be opened. No one has opened those records in over fifty years, though. Oral history, gossip, is best for this sort of situation.

Rose Addleson believed the house was trying to communicate something. She told her husband women know houses better than men, and this is one thing Rose said that we agree with. There is, after all, what is called “Women’s Intuition”. What exactly the house was saying eluded Rose, though, as it eludes the rest of us. Where Rose wanted to figure out its motivations, the rest of us would rather have seen it burn to cinders.

“All these years?” Jonas told her. It was not Rose Addleson who grew up in the house after all, who experienced the years of closeness to these events, these fits that her husband had suffered since childhood. “If it’s trying to communicate,” he said, “it has a sad idea of conversation.”

Rose and Jonas have no children. Well, to be precise, no living children. Once there had been a beautiful little girl, with cheeks that blushed a red to match her mother’s, but she did not take to this world. She died when she was only a year old. On a cold winter’s night she stopped breathing, when the house was frosted with ice. It wasn’t until the next morning that they found her, already off and soaring to the afterlife. “A hole in her heart,” the doctor said, pinching his forefinger and thumb together. “A tiny hole.” They had never known it was there.

After their first few months of marriage, Rose and Jonas had become a bit reclusive. Out of shame? Out of guilt? Fear? Delusion? No one is able to supply a satisfactory reason for their self-imposed isolation. After all, we don’t live in that house. If walls could talk, though, and some believe the walls of — House do talk, perhaps we’d understand that Jonas and Rose Addleson have good reason not to go out or talk to neig

hbors. Why even Rose’s mother Mary Kay Billings didn’t hear from her daughter but when she called on the phone herself, or showed up on the front porch of — House, which was something she rarely did. “That house gives me the creeps,” she told us. “All those stories, I believe them. Why Rose ever wanted to marry into that family is beyond me.”

Mary Kay has told us this in her own home, in her own kitchen. She sat on a chair by the telephone, and we sat across the table from her. She said, “Just you see,” and dialed her daughter’s number. A few rings later and they were talking. “Yes, well, I understand, Rose. Yes, you’re busy, of course. Well, I wanted to ask how you and Jonas are getting along. Good. Mm-hmm. Good. All right, then. I’ll talk to you later. Bye now.”

She put the phone down on the cradle and smirked. “As predicted,” she told us. “Rose has no time to talk. ‘The house, Mother, I’m so busy. Can you call back later?’ Of course I’ll call back later, but it’ll be the same conversation, let me tell you. I know my daughter, and Rose can’t be pried away from that house.”

We all feel a bit sad for Mary Kay Billings. She did not gain a son through marriage, but lost a daughter. This is not the way it’s supposed to happen. Marriage should bring people together. We all believe this to be true.

Rose heard a voice calling

She has heard voices since she was a little girl. Rose Addleson, formerly Rose Billings, was always a dear girl in our hearts, but touched with something otherworldly. If her mother doesn’t understand her daughter’s gravitation to — House, the rest of us see it all too clear. Our Rose was the first child to speak in tongues at church. Once, Jesus spoke through her. The voice that came through her mouth never named itself, but it did sound an awful lot like Jesus. It was definitely a male voice, and he kept saying how much he loved us and how we needed to love each other better. It was Jesus all over, and from our own sweet Rose.

We do not understand why, at the age of twelve, she stopped attending services.

But Rose also heard voices other than the Lord’s. Several of us have overheard her speaking to nothing, or nothing any of us could see. She’s hung her head, chin tucked into breastbone, at the grocery store, near the ketchup and mustard and pickles, murmuring, “Yes. Of course. Yes, I understand. Please don’t be angry.”

Rose heard the voices in — House, too. This is why she married Jonas: The house called for her to come to it.

It was winter when it happened. Rose was eighteen then, just half a year out of high school. She worked in Hettie’s Flower Shop. She could arrange flowers better than anyone in town. We all always requested Rose to make our bouquets instead of Hettie, but Hettie never minded. She owned the place, after all.

On her way home from work one evening, Rose’s car stalled a half mile from — House. She walked there to get out of the cold, and to call her mother. At the front door she rapped the lion-headed knocker three times. Then the door opened and wind rushed past her like a sigh. She smelled dust and medicine and old people. Something musty and sweet and earthy. Jonas stood in front of her, a frown on his sad young face. He was already an orphan at the age of thirty. “Yes?” he asked in a tone of voice that implied that he couldn’t possibly be interested in any reason why our Rose was appearing before him. “Can I help you?”

Rose was about to ask if she could use his phone when she heard a voice calling from inside. “Rose,” it whispered. Its voice rustled like leaves in a breeze. “Please help us,” the house pleaded. And then she thought she heard it say, “Need, need, need.” Or perhaps it had said something altogether different. The walls swelled behind Jonas’s shoulder, inhaling, exhaling, and the sound of a heartbeat suddenly could be heard.

“Are you all right?” Jonas asked, cocking his head to the side. “Rose Billings, right? I haven’t seen you since you were a little girl.”

“Yes,” said Rose, but she didn’t know if she was saying yes to his question or to the house’s question. She shook her head, winced, then looked up at Jonas again. Light cocooned his body, silvery and stringy as webs.

“Come in,” he offered, moving aside for her to enter, and Rose went in, looking around for the source of the voice as she cautiously moved forward.

Mary Kay Billings didn’t hear from her daughter for three days after that. That night she called the police and spoke to Sheriff Dawson. He’d found Rose’s car stuck in the snow. They called all over town, to Hettie’s Flower Shop, to the pharmacy, because Rose was supposed to pick up cold medicine for Mary Kay. Eventually Rose called Mary Kay and said, “I’m okay. I’m not coming home. Pack my things and send them to me.”

“Where are you?” Mary Kay demanded.

“Have someone bring my things to — House,” Rose said.

“— House?!” shouted Mary Kay Billings.

“I’m a married woman now, Mother,” Rose explained, and that was the beginning of the end of her.

Jonas in his cups

He had many of them. Cups, that is. Most of them filled with tea and whiskey. Jonas Addleson had been a drinker since the age of eight, as if he were the son of a famous movie star. They are all a sad lot, the children of movie stars and rich folk. Too often they grow up unhappy, unaccustomed to living in a world in which money and fame fade as fast as they are heaped upon them.

Jonas Addleson was not famous beyond our town, but his family left him wealthy. His father’s father had made money during the Second World War in buttons. He had a button factory over in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It’s long gone by now, of course. They made all sorts of buttons, the women who worked in the factory while the men were in Europe. Throughout — House you will still find a great many buttons. In the attic, on the pantry shelves, in the old playroom for the children, littered in out-of-the-way places: under beds, in the basement, among the ashes in the fireplace (unburned, as if fire cannot touch them).

This is not to say Rose Addleson was a bad housekeeper. In fact, Rose Addleson should have got an award for keeping house. She rarely found time for anything but cleaning and keeping. It was the house that did this eternal parlor trick. No matter how many buttons Rose removed, they returned in a matter of weeks.

When Rose first arrived at — House, Jonas showed her into the living room, then disappeared into the kitchen to make tea. The living room was filled with Victorian furniture with carved armrests, covered in glossy chintz. A large mirror hung on the wall over the fireplace, framed in gold leaf. The fire in the fireplace crackled, filling the room with warmth. On the mantel over the fire, what appeared to be coins sat in neat stacks, row upon row of them. Rose went to them immediately, wondering what they were. They were the first buttons she’d find. When Jonas returned, carrying a silver tray with the tea service on it, he said, “Good, get warm. It’s awfully cold outside.”

He handed Rose a cup of tea and she sipped it. It was whiskey-laced and her skin began to flush, but she thanked him for his hospitality and sipped at the tea until the room felt a little more like home.

“The least I can do,” he said, shrugging. Then remembering what she’d come for, he said, “The phone. One second. I’ll bring it to you.”

He turned the corner, but as soon as he was gone, the house had her ear again. “Another soul gone to ruin,” it sighed with the weight of worry behind it. “Unless you do something.”

“But what can I do?” said Rose. “It’s nothing to do with me. Is it?”

The house shivered. The stacks of buttons on the mantel toppled, the piles scattering, a few falling into the fire below. “You have what every home needs,” said the house.

“I’m no one,” said Rose. “Really.”

“I wouldn’t say that,” Jonas said in the frame of the doorway. He had a portable phone in his hand, held out for her to take. “I mean, we’re all someone. A son or daughter, a wife or husband, a parent. Maybe you’re right, though,” he said a moment later. “Maybe we’re all no one in the end.”

“What do you mean?” asked Rose. She put the te

acup down to take the phone.

“I’m thinking of my family. All gone now. So I guess by my own definition that makes me nothing.”

Rose batted her eyelashes instead of replying. Then she put the phone down on the mantel next to the toppled towers of buttons. She sat down in one of the chintz armchairs and said, “Tell me more.”

The first lost family

Before the Addlesons, the Oliver family lived in — House. Before the Olivers lived in — House, the family that built the house lived there. But the name of that family has been lost to the dark of history. What we know about that family is that they were from the moors of Yorkshire. That they had come with money to build the house. That the house was one of the first built in this part of Ohio. That our town hadn’t even been a town at that point. We shall call them the Blanks, as we do in town, for the sake of easiness in conversation.

The Blanks lived in — House for ten years before it took them. One by one the Blanks died or disappeared, which is the same thing as dying if you think about it, for as long as no one you love can see or hear you, you might as well be a ghost.

The Blanks consisted of Mr. Blank, Mrs. Blank, and their two children, twin boys with ruddy cheeks and dark eyes. The photos we have of them are black and white, but you can tell from the pictures that their eyes are dark and that their cheeks are ruddy by the serious looks on their faces. No smiles, no hint of happiness. They stand outside the front porch of — House, all together, the parents behind the boys, their arms straight at their sides, wearing dark suits.

The father, we know, was a farmer. The land he farmed has changed hands over the years, but it was once the Blank family apple orchard. Full of pinkish-white blossoms in the spring, full of shiny fat globes of fruit in autumn. It was a sight, let us tell you. It was a beautiful sight.