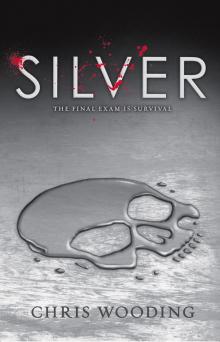

Silver

Chris Wooding

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

Darkness.

Crushing pressure on his neck. The sour tang of another boy’s sweat. The rough fabric of a blazer rasping against his face.

Pain, as a fist thumped hard into his back.

Paul struggled wildly against the headlock. He swung with his arms, hit his attacker a glancing blow. But the other boy was bigger than him, and all he got in return was another punch, right in the kidneys.

Through the blazer that was tangled round his head, Paul heard his classmates shouting, their cries muffled.

Fight! Fight! Fight!

He lashed out, and this time he made a solid connection, driving his knuckles into soft belly fat. His opponent whuffed out his breath, and for a moment the pressure on his head loosened. Paul yanked back violently, punching again, and suddenly he was free.

Daylight. The lake was at his back, sun-bright woods all around, leaves glistening with the memory of rain. Clouds skidded fast across a summer sky.

Paul backed away a step, cheeks flushed and hot. Falling for that headlock had made him embarrassed and angry. Adam glared at him, fists bunched, his thuggish face screwed up in a fighting scowl. He was bigger than Paul, and more thickly built, but there was no retreat now.

Fight! Fight! Fight!

The students had abandoned their biology assignments the moment the scuffle broke out. The boys chanted like they were the audience to a gladiatorial combat. The girls made a show of their disgust but watched anyway. Paul looked for Erika in the crowd but found only Caitlyn, her narrow, sharp features a picture of concern, bird-bright eyes fixed on him.

“Go on, Paul!”

“Do him in!”

“Come on, Paul!”

Fight! Fight! Fight!

Maddened, Adam charged. Instead of meeting the charge, Paul sidestepped, leaving a trailing leg for Adam to trip on. The bigger kid went down, crashing to the ground. The crowd broke into laughter. They all wanted to see Adam eat dirt. Paul danced away a step, exhilarated, knowing that he’d scored a point.

A sharp, cold gust of wind whipped through the woods, rippling the lake and setting the branches lashing overhead. Paul felt a grin coming. The day felt unsettled, like a storm was on its way. There was chaos in the air.

His kind of day.

Adam began to pick himself up, his small eyes hateful. His ears burned red with rage and humiliation. Paul expected Adam to get to his feet, but Adam surprised him by lunging from a crouch. Paul wasn’t ready, and wasn’t quick enough to avoid it. Adam wrapped his arms round Paul’s legs and drove into his thighs, knocking him backward.

Suddenly Paul was on the ground, and Adam was on top of him, punching, frenzied. Paul barely felt the hits. He fought back, thrashing like an animal, and managed to shift Adam’s weight before he could be pinned. They rolled, and then Paul was on top, raining blows on his opponent. But Adam was too big to keep down: A moment later, they were rolling again. They scuffled and scrabbled, a mass of jabbing elbows and knees, trying to land hits on each other in a sweaty, furious tussle. And all the time, the hypnotic chant of the crowd:

Fight! Fight! Fi —

“YOU TWO!”

Mr. Harrison’s voice sliced through the morning air, killing the heat of the fight in an instant. The chanting was silenced. The spell was broken: The crowd looked guilty and abashed.

Paul and Adam got to their feet, dusting leaves off their blazers, neither taking their eyes from the other. Mr. Harrison stood at the top of the slope, beyond which lay the school and the sprawling grounds of Mortingham Boarding Academy. The headmaster didn’t trouble himself to come through the wood to the lake. He just stood there like some disapproving god gazing down on his wayward flock.

“I’ll see you both in my office at the end of this period!” he said in that hammered-steel drill-sergeant voice that every Mortingham pupil had learned to dread. “Is that understood?”

Neither Paul nor Adam said a thing. They just glared at each other, panting.

“Is that understood?” Mr. Harrison barked.

“Yes, sir,” they both mumbled reluctantly.

Just then, Mr. Sutton came hurrying through the trees, led by Erika, who’d apparently run to fetch him from the other side of the lake when the fight started. He took in the scene with a glance and sighed.

“Everything under control here, Mr. Sutton?” Mr. Harrison asked. Nobody missed the pointed sarcasm in his voice.

“Everything’s under control,” Mr. Sutton said. “Isn’t it, boys?” He looked from Adam to Paul, and Paul thought he saw disappointment in that calm gaze. He was surprised by a pang of guilt.

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Harrison stared down at them for a long moment, then stalked off and out of sight. Mr. Sutton’s gaze swept the assembled crowd.

“Well, what are you all doing here? That biomass won’t weigh itself, you know! I want every worm, every beetle in your sample zone collected up and recorded. Get to it.”

He clapped his hands and the crowd dispersed, heading back to their sample zones. Each zone was staked out with four poles, red thread strung between them, marking out a square meter of undergrowth. One student in each zone was in charge of collecting the insects; one was in charge of recording what they found.

“Come on,” said Mr. Sutton to Paul and Adam. “You’ve had your fun. Get back to work. We’ll talk about this later.”

As he was led away from the others, Paul saw Erika watching him. He flashed her a savage grin. She narrowed her eyes and looked away.

Mr. Harrison’s office was located in the heart of Mortingham Boarding Academy. The massive central building had once been a workhouse for the poor, then a sanatorium for tuberculosis sufferers, before ending up as a school, which Paul hardly counted as an improvement. It seemed to him that all that concentrated unhappiness had soaked into the walls over time, and turned its stony halls oppressive and gloomy. There was a sense of confinement here that wasn’t present in the more modern buildings that surrounded it. One way or another, this place had always imprisoned its occupants.

Paul stood in front of Mr. Harrison’s mahogany desk and looked out of the thin, arched windows while he waited for the headmaster to finish paging through the folder of reports in his hand.

The grounds were huge, big enough to encompass a small lake, playing fields, tennis courts, half a dozen dorm buildings, and accommodation for staff and visitors. There was a state-of-the-art sports hall with an Olympic-size swimming pool. There was a theater, an ancient library, even an old ruined chapel that the younger students told ghost stories about.

But all of it was inside the wall. Ten feet high, solid stone, it had a single gate that was the only exit from the campus.

And outside? Nothing. Green valley walls swept up to gray, rocky peaks. Sheep wandered in meadows bordered by trees and dry stone walls. The only sign o

f human life in that beautiful, desolate world was the weather-monitoring station that sat on a ridge several miles down the valley. It was stark white against the landscape, all domes and angles.

There was a single road that snaked away down the valley, following the slender river. At its end was Mortingham town, and the gateway to civilization and the rest of the world. Or so Paul had heard, at least. He’d been here six months, and he’d never left for so much as a day trip.

“Now, then,” said Mr. Harrison.

Paul returned his attention to the headmaster. Mr. Harrison was sitting back in his chair, gazing at Paul with those gray, dead-fish eyes of his. He was a big man with wide shoulders, a little overweight, and he had the kind of face Paul associated with authority. He looked like the bad cop in all those eighties TV shows Dad used to watch: bald on top, brown mustache, an expression like a bulldog chewing a wasp. Even his clothes seemed thirty years out of date.

“Now, then,” he said again, with the oily manner of a bank clerk eager to please a customer. “How can we help you settle in to our fine establishment, Mr. Camber?”

Paul wasn’t fooled by his tone. He didn’t want to give Mr. Harrison the satisfaction of playing along with his game, but he had to say something. So he just said, “Dunno, sir.”

“He doesn’t know,” Mr. Harrison said to Mr. Sutton, who was standing quietly to one side. Mr. Sutton was Paul’s housemaster as well as his biology teacher, and as such he’d felt it necessary to come along. Paul felt sorry that he’d been dragged into this. Mr. Sutton was a decent guy.

“The reason I ask,” Mr. Harrison continued, his tone hardening, “is because I have on my desk a series of reports from your previous school. Let me quote a few for you.” He began to leaf through the pages. “‘Well-behaved,’ this one says. ‘Exceptional pupil,’ ‘Gets along well with others,’ ‘Natural leader.’” He closed the folder and gave Paul another dose of that unblinking stare. “Do you have a twin brother I don’t know about?”

Paul supposed that was what passed for wit among headmasters. “No, sir.”

Mr. Harrison whipped out another sheet of paper. “Your preliminary report from Mortingham Academy. We do these on all new students. Let me see…. ‘Does just enough work to get by,’ ‘Has potential but refuses to apply himself.’ Oh, here’s a good one: ‘Doesn’t listen to instructions.’” He put the report down. “Anyone would think you didn’t want to be here.”

Paul didn’t answer that. He didn’t want to be here. But then, he didn’t exactly have anywhere else he could go, either. He was suddenly taken by that awful feeling that sometimes crept up in the night, as if he were falling into endless emptiness and he couldn’t stop himself. Panic fluttered in his chest. He swallowed it back and stared straight ahead.

“Well, you are here, Mr. Camber,” said Mr. Harrison. He got to his feet and leaned over the desk, his voice rising to a shout. “And while you’re here, you will obey the rules!”

It was hard not to be intimidated by a man of Mr. Harrison’s size bellowing in your face. He was a man permanently on the edge of boiling point. It wasn’t uncommon to see younger students reduced to tears after a roasting from the headmaster. Paul just looked down at the floor.

“Yes, sir,” he said, because that was what was expected. That was what would get this whole thing over with.

“I’ve been a teacher here for twenty-five years,” Mr. Harrison said. “I’ve seen a hundred boys like you. You all think you know better. You all think you’re something special. But year after year, you’re all the same.”

Paul didn’t rise to it. There wasn’t any point arguing; he’d learned that. Nobody was interested in his opinion. His job was to stand still and be talked at until the talking was done.

“I won’t bother asking who started it; I already know,” said Mr. Harrison. “We had Adam’s brother here for a few years. Nasty piece of work, he was, and they’re cut from the same cloth. I expected better from you.”

Paul kept his silence. Eventually, seeing that he’d get no reaction, Mr. Harrison humphed dismissively. He walked across the office and looked out the window. “Strange kind of day, isn’t it? Weatherman can’t make up his mind if it’ll be hot all weekend, or if the sky’s going to fall.” He turned toward Paul. “Won’t matter to you, anyway. You’ll spend the rest of July indoors. You’re confined to dorms till the end of term. Go back to your hall straight after lessons. I don’t want to see you outside. Not at break time, not at lunchtime, not after school. You can catch up on work while your friends are out having fun.” He looked away, back out the window. “Off you go.”

Paul accepted his punishment without much emotion. Mr. Sutton led him out of the office. Sitting on a bench by the door was Adam, who stared at him with sullen suspicion and threat in his eyes. What’ve you been saying in there? You better not have snitched.

“You can go in now, Adam,” said Mr. Sutton in his soft and sympathetic voice.

Adam levered his bulk out of the chair and sloped inside. “Ah, Mr. Wojcik! What a surprise to see you here!” Mr. Harrison cried before the door closed and left Mr. Sutton and Paul alone in the corridor.

Paul rolled his shoulder. He was still a little sore from the fight, but it would fade in a few hours.

“What have you got next?” Mr. Sutton asked.

“DT,” Paul replied. Design and Technology.

Mr. Sutton checked his watch. “Not long left till end of break. I’ll walk you to the science block.”

Paul would rather have been alone, but he couldn’t think of an argument. Besides, he felt he owed his housemaster something. He knew his behavior had made Mr. Sutton look bad in front of the headmaster.

They walked together in silence. With all the students outside, it seemed eerily deserted in the school. Footsteps echoed. The laughter and shouts from the grounds could be heard only faintly in here, stifled by the stone walls.

They came to a corner at the end of the corridor. There, sitting on a window seat in an alcove, was a boy Paul vaguely recognized from his classes. He was skinny and redheaded, with a high forehead, and he was anxiously tapping his heels against the wall. As Paul appeared, the boy stopped tapping and looked up at him expectantly, fixing him with an eager gaze. In that moment, Paul was convinced that he was about to spring off the window seat and say something.

But he didn’t. The boy’s eager expression faded, and Mr. Sutton gave him a look that Paul couldn’t read. Then the moment passed, and they walked on, leaving Paul with the distinct sensation that he’d missed something.

They came out of the main entrance of the school, onto the graveled courtyard where older students loitered in groups and Year Sevens ran around playing tag. Paths wound off across the grounds, leading to other buildings nearby. A long drive stretched away south to the gate, splitting halfway down to encircle a round lawn dominated by a massive ornamental fountain.

Paul glanced at Mr. Sutton, who was loping alongside him on the path. He was tall and rangy, with a long face and floppy brown hair. He had sad, watery eyes, but he always seemed to have half a smile on his face, as if he was secretly pleased at something. His clothes were always dull and a bit shabby. He was probably in his late thirties, but he had that droopy English-professor look that made him seem older. A pipe-and-slippers kind of man.

“You want to tell me what happened?” Mr. Sutton asked eventually.

Paul didn’t, really. “It’s stupid,” he said. “Shouldn’t have done it.” He met the teacher’s gaze, then looked away, over toward the mountains in the distance. “Sorry, sir.”

“Still, I’d like to know. I put you two together for a reason.”

That surprised Paul. “What reason’s that?”

“To see if you could get along with him.”

Paul snorted. “That didn’t work out too well, did it, sir?”

“Apparently not,” said Mr. Sutton. They walked on a few more steps. “So what happened?”

Paul realized that M

r. Sutton wasn’t going to let this go. “He kept getting it wrong,” he said. “I was meant to collect up the insects; he was supposed to identify them. You gave us those checklists with pictures and everything.” He felt himself reddening. It sounded so petty now that he said it aloud. “He kept putting ticks in the wrong boxes. I don’t know if he was doing it on purpose or if he’s just too stupid to count the spots on the back of a ladybird, but —”

“Paul …,” Mr. Sutton warned.

“Well, he is stupid!” Paul snapped. “I know you’re supposed to tell us that we’re all precious, unique little snowflakes and that, but the truth is, some people are just dumb.”

Mr. Sutton didn’t say anything, but somehow his silence made Paul feel ashamed of his outburst.

“Anyway,” he said. “So I took the sheet and started marking them in myself.”

“That was Adam’s job.”

“He couldn’t do his job.”

“So why didn’t you help him do it, instead of taking it away from him?”

“Didn’t seem worth it,” Paul said. “Easier to do it myself.”

They walked on a little way. Paul watched some kids kicking around a soccer ball, and remembered how he used to play all the time until recently. It felt sort of pointless now.

“I was talking with Bobby Farrell today,” Mr. Sutton said. “You know him, don’t you?”

“Faz? Yeah. I mean, we hang out a bit.”

“Would you say he’s your best friend at Mortingham?”

That seemed a weird thing to ask. “Erm,” said Paul uncertainly. “He’s alright. Wouldn’t say he was my best mate or anything.”

“So who is?”

Paul began to feel awkward. He wasn’t sure what Mr. Sutton was driving at, but he didn’t really want to be discussing his personal life with a teacher. “Dunno, sir. I hang out with a lot of different people, I s’pose. Why? What did Bobby say?”

“Oh, nothing very specific. He asked if I knew what your parents did.”

Paul froze up inside. The kids playing soccer seemed suddenly far away, as if they were separated from him by something more than distance. He felt like if he called out to them, they wouldn’t hear him. He kept walking toward the science block, one foot in front of the other, but a sense of terrible loneliness had descended on him.