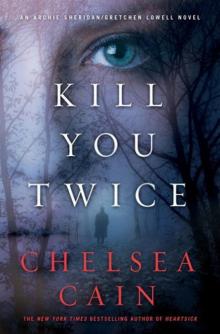

Kill You Twice

Chelsea Cain

For Carolyn Keene. I refuse to believe that you aren’t real.

Sweet as sugar

Hard as ice

Hurt me once

I’ll kill you twice.

—Unknown

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 35

CHAPTER 36

CHAPTER 37

CHAPTER 38

CHAPTER 39

CHAPTER 40

CHAPTER 41

CHAPTER 42

CHAPTER 43

CHAPTER 44

CHAPTER 45

CHAPTER 46

CHAPTER 47

CHAPTER 48

CHAPTER 49

CHAPTER 50

CHAPTER 51

CHAPTER 52

CHAPTER 53

CHAPTER 54

CHAPTER 55

CHAPTER 56

CHAPTER 57

CHAPTER 58

CHAPTER 59

CHAPTER 60

CHAPTER 61

CHAPTER 62

CHAPTER 63

CHAPTER 64

CHAPTER 65

CHAPTER 66

CHAPTER 67

CHAPTER 68

CHAPTER 69

CHAPTER 70

CHAPTER 71

CHAPTER 72

CHAPTER 73

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHAPTER

1

Archie Sheridan slept with the light on. The pills on his bedside table were Ambien. A year before they would have been pain pills. Vicodin. Oxycodone. A cheerful skyline of amber plastic bottles. Even now the table looked empty without the clutter. Just the Ambien, a cell phone, a week-old glass of tap water, and a red gooseneck lamp from IKEA.

His kept his gun in the drawer. On the nights the kids weren’t there, he slept with it loaded.

The Ambien prescription was untouched. Archie just liked to know it was there. Sleeping pills made Archie groggy, and groggy wasn’t a luxury he could afford. If the phone rang, if someone died, he needed to go to work.

Besides, it wasn’t getting to sleep that was the problem. It was staying asleep. He woke up every morning at three A.M., and was awake for an hour. That was how it had gone since the flood. Now he just figured it in. Went to bed an hour earlier. Compensated. He didn’t mind it. As long as he controlled his thoughts, kept his mind from wandering to bad places, he was fine. Focus on the present. Avoid the dark.

The gooseneck lamp stayed on, its red metal shade getting hotter by the hour.

Three-ten A.M. Archie stared at the ceiling. The apartment was sweltering and his bedroom window was open. He could hear the distant grind of the construction equipment still working to clean up the flood damage downtown. They’d been at it in swing shifts for three months, and the city still looked gutted.

If it wasn’t the noise from the construction, it was the trains he heard at night: the engines, the whistles, the wheels on the tracks. They traveled through Portland’s produce district around the clock.

Archie didn’t mind the noise. It reminded him that he wasn’t the only one awake.

Everyone had a cure for insomnia. Take a warm bath. Exercise. Drink a glass of warm milk. Eat a snack before bedtime. Drink herbal tea. Avoid caffeine. Listen to music. Get a massage.

Nothing worked.

His shrink told him to stay in bed.

Don’t even read, she said. It would just make getting back to sleep harder.

He just had to lie there.

But his pillow was too flat. The used mattress he’d bought groaned every time he turned over.

The heat made his scars itch. The new skin was tight and prickly, reminding him of every place her blade had sliced his flesh. His chest was knitted with scar tissue. Patches of dark hair sprouted around the thick pale pink gashes and pearly threads, unable to grow through the tough flesh.

That sort of itching, in the middle of the night, can make a person crazy, and sometimes, while he slept, he scratched his scars until they bled.

Archie ran a hand along his side, the scars pebbly under his fingers, and then over his chest, where his fingers found the heart-shaped scar she had carved into him with a scalpel. Then he made a fist with his hand, rolled over, and pinned it under his pillow.

Four-ten A.M.

Archie’s cell phone rang. He turned over in bed and looked at the clock on his bedside table. He’d been asleep ten minutes. It seemed like longer. His eyeballs felt gritty, his tongue coated. His hair was damp with sweat. He was on his stomach, naked, half his face smashed against the pillow. As he reached out and fumbled for his phone he knocked over the bottle of Ambien, which toppled and rolled off the bedside table and clattered to a stop somewhere under the bed.

Archie brought the phone’s glowing LCD screen to his face and immediately recognized the number.

He knew he should let it go to voice mail.

But he didn’t.

“Hi, Patrick,” Archie said into the phone.

“I can’t sleep,” Patrick said. His voice was a strained whisper. Probably trying not to wake up his parents. “What if he comes back to get me?” Patrick said.

“He’s dead,” Archie said.

Patrick was silent. Not convinced.

The official report had been death by drowning. A half-truth. Archie had held Patrick’s captor’s head underwater, and when he was dead, he had pushed his body into the current of the flooded river.

The corpse still hadn’t surfaced.

“Believe me,” Archie said. Because I killed him.

“Will you come and visit me?” Patrick asked.

“I can’t right now,” Archie said.

“Can I come and visit you?”

Archie rolled over on his back and rubbed his forehead with his hand. “I think your parents want to keep you close right now.”

“I heard them talking about me. They want to give me medicine.”

“They’re trying to help you feel better.”

“I have a secret,” Patrick said.

“Do you want to tell me what it is?” Archie asked.

“Not yet.”

Archie didn’t want to force it. Not after what Patrick had been through. “Okay,” he said.

“Will you count with me?” Patrick asked. It was something Archie had done with his own son. Counting breaths to get to sleep. Patrick and Ben were both nine. But Patrick’s experience had left him changed. He was mature without being sophisticated.

“Sure,” Archie said. He waited. He could hear Patrick getting settled and imagined him curled on his side on the couch in his family’s living room, the phone held to his ear. Archie had never seen that couch, that house, but he’d seen photographs in the police file. He could picture it.

“One,” Archie said. He paused and listened as Patrick drew a breath and exhaled it. “Two.” Archie sat up in bed. Patrick yawned. “Three.” He put his feet

on the floor. “Four.” Stood up. “Five.” The windows in his bedroom were original, made up of dozens of factory-style rectangular panes. If Archie ran his fingers over the glass, he could feel tiny waves and ripples on the surface.

“Six,” he said.

He made his way to the window. “Seven.” The light was on inside, and it was still dark enough outside that Archie could see his own mirror image in the glass. As he got closer, his reflection faded and the city appeared. Out his window the Willamette cut a curved path north, slicing the city in half. A sliver of light along the silhouette of the West Hills marked the first hint of dawn. The river was almost lilac-colored.

“Eight,” he said.

It was the truck’s backup alarm that caught his attention. The window was open, hinged along the top so that it swung out horizontally. Archie’s eyes flicked down to the street below.

“Nine.”

The streetlights were still on. The produce district had wide streets, built big enough for multiple trucks full of apples and strawberries. But the trucks didn’t run much anymore. The warehouses were now mostly home to used office supply stores, fringe art galleries, Asian antique stores, coffeehouses, and microbreweries. It was close in and cheap, as long as you didn’t mind the trains that barreled through the neighborhood every few hours.

“Ten.”

The truck down below had backed up to the loading dock of Archie’s building and stopped. A black sedan pulled up beside it. Two men got out of the cab of the truck and walked around to slide the back door up. A woman got out of the black car. Archie knew she was a woman the same way he knew that the men in the truck were men. It was how they stood, how they moved, the dark shapes of their bodies in the yellow glow of the streetlights. The woman said something to the men, and then took a few steps back and watched as the men started unloading large cardboard boxes from the truck.

A U-Haul.

Someone was moving into the building. At four in the morning.

Archie had stopped counting.

“Patrick?” he said.

The other end of the line was silent.

“Good night,” Archie whispered.

He ended the call. It was 4:17 A.M. The bed beckoned. He could still get a few hours’ sleep before he had to head in to the office. As he stepped away from the window, he thought he saw the woman look up at him.

CHAPTER

2

Jake Kelly only drank fair trade coffee. It guaranteed a living wage for coffee farmers, who otherwise might be slaving away for a price less than the cost of production, forcing them into a cycle of debt and poverty. Jake needed a cup. He needed the caffeine. But the center only had Yuban. He could smell the nutty aroma of French roast wafting from the brewing air pot. Was he tempted? Yes. But then he thought of the indigenous people of Guatemala, working for pennies in the coffee fields. Every choice a person made, what to buy or not to buy, what to eat and drink, had the power to change lives. You were either part of the solution or part of the problem.

He focused on the task at hand.

The trick to cleaning a griddle was kosher salt. Jake let the griddle cool and then scraped it with a plastic spatula. Charred pancake batter collected in satisfying little clumps. He’d brought his own yellow rubber gloves. The center didn’t have any, and it didn’t seem right to ask them to spend money on that sort of thing. He’d brought the kosher salt, too. It was Morton’s, in a blue box with the girl in the yellow dress carrying an umbrella on the label. He sprinkled some salt on the griddle. The coarse white granules bounced and scattered on the cast iron like hail raining down on a sidewalk. You didn’t want to use soap or detergent. Jake scrubbed the griddle with a pumice brick, grinding the salt against the surface until his fingers ached. Then he used a damp cloth to wipe up all the salt and muck it had loosened. It took five passes with the cloth until the surface of the griddle gleamed.

He wasn’t done. He unscrewed the plastic cap of an economy-sized bottle of vegetable oil and drizzled a thread of it on the cast iron. Then he got yet another cloth rag and used it to work a thin coat of oil over the entire surface of the griddle. More oil. More rag work. Small circular motions. Start at the center. Work your way out.

He was bent over, eyes even with the surface of the griddle, inspecting his work, when Bea, the center’s director, walked into the kitchen carrying a plastic laundry basket piled high with dirty linens. She was a sturdy woman, old enough to be Jake’s mother, with the wild hair and anxious eyes of someone who has just stepped out of a very fast convertible.

“You’re still here,” she said.

Jake glanced at the oven clock and realized that his shift had been over for an hour.

“I’m seasoning the griddle,” he explained.

She smiled. “You don’t have to do that.”

“I don’t mind.”

“The last volunteer just used paper towels and 409,” she said.

“I’m sure they did what they thought was best.” He hadn’t known how to take care of a griddle, either. But he’d seen it on his orientation tour of the kitchen, and afterward he’d looked it up. He’d taken notes, copying down bullet points from various Web sites. People could get pretty passionate about the proper care of griddles. After reading some of what he found on the Web, Jake began to wonder if it wouldn’t be easier to just make the girls’ pancakes in a skillet. He thought about suggesting that, but he didn’t want to make waves.

“I wish we had more volunteers like you,” Bea said. She blew a stray piece of graying hair off her forehead, adjusted her grip on the basket, and headed for the back door.

Jake peeled off the yellow gloves, tucked them in his apron pocket, and ran after her to help. “What’s with the laundry?”

“Washer’s broken. I was going to put this in my car so I don’t forget to take it home tonight.”

Jake didn’t even hesitate. “I’ll take it,” he said.

She frowned and raised an eyebrow. “Really?”

Jake took the laundry basket from her hands. It was heavier than it looked. Or maybe she was stronger than she looked. “Let me take it home. I have to do laundry anyway tonight. I can bring it back in the morning.”

Bea crossed her arms and shook her head with a smile. “You’re a blessing, Jake.”

Jake beamed. “I’m happy to help.”

“You want some help getting it to your car?” she asked.

“I’ve got it, thanks.”

Bea opened the back door for him anyway, and he lugged the basket out to his car. The center had a small parking lot, five spaces, just enough for staff and volunteers. Three of the cars in the lot were silver Priuses. Jake took the basket to his silver Prius and set it down on the pavement so he could open the trunk. He paused to look up at the sky. The morning sun on his face was warm and the cool summer breeze tickled the hair on the back of his neck. A white butterfly spiraled lazily through the air, dipping in and out of view. Not a cloud in the sky. Jake closed his eyes and put his face up to the sun. In the Pacific Northwest, days like this were precious.

He smelled something—sandalwood? cloves?—and opened his eyes. The butterfly was gone.

Then he heard a thud, like a baseball bat hitting a melon, and felt a searing pain in his head that knocked him off his feet. It took him a few seconds to realize that the two sensations were related. As he lay there on the concrete, slipping into darkness, the last thing he saw was the laundry basket beside him, a fine mist of blood settled on the dirty sheets like dew.

CHAPTER

3

Human meat had a particular smell. It was blood and flesh, metallic and salty, feces and fat. Like the slaughterhouse stench of butchered animals, but different.

Sourer.

It was a smell that Archie had trouble describing, but always knew immediately.

The dead man’s wrists and ankles were bound with rope and he was dangling from the lower branch of a cedar tree, his hands tied to the branch so he hung like a sick Ch

ristmas ornament, his bare feet a few inches from the ground. He appeared to have been skinned from the neck down. The beefy red muscles of his chest wall gave off a bloody gleam, and the lacelike threads of exposed yellow fat looked almost pretty against the raw meat of his flesh.

The weekend summer sun was high and bright, and there was a cool breeze that belied the late afternoon heat to come. Rays of sunlight pierced through the cedar boughs. The corpse’s light hair fluttered gently along with the leaves. He looked to be in his mid-thirties, average height and weight. But it was hard to tell.

At the corpse’s feet, already marked with an evidence flag, was a wilted white lily.

Cedar needles covered the ground beneath the body, and where the cedar needles gave way to earth, the dirt had been raked clean with a branch, obscuring any footprints.

Archie bent his ear to listen to the distant sounds of children playing echoing through the woods.

Henry had arrived at the scene first, and his shaved head was already glistening with tiny beads of sweat. He looked off into the distance. “Playground,” he explained.

Archie knew the park. Ben and Sara played there.

They were on Mount Tabor, which was less of a mountain and more of an impressive hill with high aspirations. It rose up on Portland’s flat east side, a dormant volcanic cinder cone, its slopes covered with elegant historic homes nestled among ancient conifers. The top of Mount Tabor was a wooded park. There were hiking trails. Tennis courts. Picnic areas. A crenellated stone water reservoir. A popular playground. Every August hundreds of adult Portlanders built soapbox cars, dressed up in costumes, and raced from the top of the park, down the winding road to the bottom of the hill.

“I’ll clear the area,” Henry said. He turned and headed off toward one of the patrol units on the road. He still walked with a limp, though Archie could tell that he tried hard to hide it.

“How is he?” Robbins asked once Henry was out of earshot. Robbins had his medical examiner’s kit open, and had bagged the body’s hands. Now he stood with his fists on the hips of his white Tyvek suit, studying the corpse like a butcher sizing up a cut of meat.

“Still weak,” Archie said.

“Physical therapy?” Robbins asked.