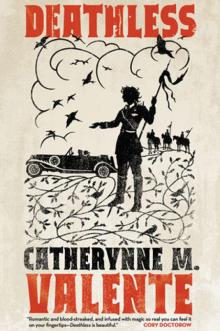

Deathless

Catherynne M. Valente

For Dmitri,

who spirited me away from a dark place

From the year nineteen forty

I look out on everything as if from a high tower

As if bidding farewell

To that from which I long ago parted.

As if crossing myself

And descending beneath dark arches.

—ANNA AKHMATOVA

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part 1: A Long, Thin House

1. Three Husbands Come to Gorokhovaya Street

2. The Red Scarf

3. The House Committee

4. Likho Never Sleeps

5. Who Is to Rule

6. The Seduction of Marya Morevna

Part 2: Sleep with Fists Closed and Shoot Straight

7. The Country of Life

8. Sleep by Me

9. A Girl Not Named Yelena

10. The Raskovnik

11. White Gold, Black Gold

12. Red Compels

13. The Tsar of Life and the Tsar of Death

Part 3: Ivanushka

14. All These Dead

15. Dominion

16. The Constant Sorrow of the Dead

17. A Pain Where My Death Once Lay

18. What We Carry Between Us

19. Three Sisters

Part 4: There Are No Firebirds in Leningrad

20. Two Husbands Come to Dzerzhinskaya Street

21. This House Has No Basement

22. Each of Them Uncatchable

23. A War Story Is a Black Space

Part 5: Birds of Joy and Sorrow

24. Nine Shades of Gold

25. Gross Desertion

26. What Will We Call Her?

27. The Sound of Remembering

28. I Saw a Rook in the Ruins

Part 6: Someone Ought to Be

29. Every One Written on Your Belly

30. The Country of Death

Acknowledgments

Also by Catherynne M. Valente

Copyright

PROLOGUE

Don’t Look Behind You

Woodsmoke hung heavy and golden on the shorn wheat, the earth bristling like an old, bald woman. The apple trees had long ago been stripped for kindling; the cherry roots long since dug up and boiled into meal. The sky sagged cold and wan, coughing spatters of phlegmatic sunlight onto the grey and empty farms. The birds had gone, arrows flung forth in invisible skirmishes, always south, always away. Yet three skinny, molting creatures clapped a withered pear branch in their claws, peering down with eyes like rosary beads: a gold-speckled plover, a sharp-billed shrike, and a bony, black-faced rook clutched the greenbark trunk. A wind picked up; it smelled of clover growing through the roof, rust, and old, dry marrow.

The boy stood sniffling, snot and tears dripping down his chin. He tried to knuckle it away, rubbing his nose red and scratching his belly with the other scuffed-up hand. His hair was colorless, his age vague, though no fuzz showed on his face, no squareness set his jaw, and his ribs would have been narrow even if they had meat on them. His eyes drooped, too tired to squint in the autumnal light. The sun slashed through his pupils, stirring shadows there.

“Comrade Tkachuk!” A young woman’s voice cut through the brisk, ashy wind like scissors. “You have been accused of desertion, gross cowardice in the face of the enemy. Do you deny this?”

The boy stared at the pair of officers and their polished tribunal bench, dragged from a truck into this wasted field for the purpose of punishing him, as though the army were a terrible stern mother, and he a child who had not come to dinner when called. His nose dribbled.

“On the eighteenth of June,” continued the staff sergeant, her pen scratching against her notepad like a bird in the dust, “did you report for service when Lieutenant-General Tereshenko opened his books to the village of Mikhaylovka so that all might know glory on earth through the gift of their bodies to the People?”

“N-no…” mumbled the boy, his voice thick and slurred, an illiterate voice, a field hand’s lazy vowels. The officer’s nose wrinkled in distaste.

“Why not?” she barked, the buttons on her olive uniform blinking like eyes in the sun.

“I … I’m … eleven, ma’am.” The sergeant frowned, but did not open her arms to him, did not gather him up or smooth his hair or feed him bread. He hurried on. “And I got this bad leg. Broke when I were six. I … I falled out a cherry tree. The man come with his big book, and I run and hidded with the pigs. Don’t want t’be in the army. Wouldn’t be no good soldier anyhow.”

The staff sergeant’s gaze sharpened itself on the boy’s fumbling speech. “The service of your body is not yours to give as you please. It belongs to the People, and you have stolen from us by means of your weakness. However, the People are not unkind. Just as you chose to hide among pigs rather than serve among lions, you may now choose your reprimand: execution by firing squad, which is no more than you deserve, or service in a penalty battalion.”

The boy stared, his eyes glassy and mute.

“That will be the front lines, son,” said the senior officer, her rough voice honey-full of infinite mercy. The rook ruffled her feathers; the shrike clacked her beak. The plover called, mournful and high. A wind kicked at the grasses, then, sudden and brief, neither warm nor sweet. The senior officer’s thick, dark hair was plaited around her head like a corona, her stare hard and tired. “You probably won’t survive. But you might. You’re small; we all were, once. You could be missed in the ranks. It has been known to happen.”

The staff sergeant looked bored. She made a note on her pad. “Comrade Tkachuk, what is it you want?”

The boy said nothing for a moment, his gaze moving between the two officers, seeking mercy like a boar snuffling for mushrooms in the loam. Finding nothing, he simply started to cry: thin, dry, starved tears cutting through the dirt on his face. His little chest heaved jerkily; his shoulders shook as though snow was already falling. He rubbed his nose furiously on a bare arm. Blood showed pinkish in the mucus.

“I want t’go home,” he sobbed.

The plover shrieked as though pierced with long thorns. The shrike hid her face. The rook could not bear witness—she opened her black wings to the air.

Major-General Marya Morevna sat impassively and watched the child weep. The staff sergeant tapped her pen impatiently.

“Go,” Morevna whispered. “Run. Don’t look behind you.”

The boy looked at her dumbly.

“Run, boy,” the major-general whispered.

The boy ran. Flecks of dead earth flew up behind him. The wind caught them, and carried them away towards the sea.

PART 1

A Long, Thin House

And you will arrive under a soldier’s black mantle

With your fearful greenish candle

And will not show your face to me.

But the riddle cannot torment me for long:

Whose hand is here, under that white glove

Who sent this wanderer, who comes in darkness?

—ANNA AKHMATOVA

1

Three Husbands Come to Gorokhovaya Street

In a city by the sea which was once called St. Petersburg, then Petrograd, then Leningrad, then, much later, St. Petersburg again, there stood a long, thin house on a long, thin street. By a long, thin window, a child in a pale blue dress and pale green slippers waited for a bird to marry her.

This would be cause for most girls to be very gently closed up in their rooms until they ceased to think such alarming things, but Marya Morevna had seen all three of her sisters’ husbands from her window before they knocked at the great cherrywood door, and thus she

was as certain of her own fate as she was certain of the color of the moon.

The first came when Marya was only six, and her sister Olga was tall as she was fair, her golden hair clapped back like a hay-roll in autumn. It was a silvery damp day, and long, thin clouds rolled up onto their roof like neat cigarettes. Marya watched from the upper floor as birds gathered in the oak trees, sniping and snapping at the first and smallest drops of rain, which all winged creatures know are the sweetest, like tiny grapes bursting on the tongue. She laughed to see the rooks skirmish over the rain, and as she did, the flock turned as one to look at her, their eyes like needle points. One of them, a fat black fellow, leaned perilously forward on his green branch and, without taking his gaze from Marya’s window, fell hard—thump, bash!—onto the streetside. But the little bird bounced up, and when he righted himself, he was a handsome young man in a handsome black uniform, his buttons flashing like raindrops, his nose large and cruelly curved.

The young man knocked at the great cherrywood door, and Marya Morevna’s mother blushed under his gaze.

“I have come for the girl in the window,” he said with a clipped, sweet voice. “I am Lieutenant Gratch of the Tsar’s Personal Guard. I have many wonderful houses full of seed, many wonderful fields full of grain, and I have more dresses than she could wear, even if she changed her gown at morning, evening, and midnight each day of her life.”

“You must mean Olga,” said Marya’s mother, her hand fluttering to her throat. “She is the oldest and most beautiful of all my daughters.”

And so Olga, who had indeed sat at the first-floor window, which faced the garden full of fallen apples and not the street, was brought to the door. She was filled like a wineskin with the rich sight of her handsome young man in his handsome black uniform, and kissed him very chastely on the cheeks. They walked together down Gorokhovaya Street, and he bought for her a golden hat with long black feathers tucked into its brim.

When they returned in the evening, Lieutenant Gratch looked up into the violet sky and sighed. “This is not the girl in the window. But I will love her as though she was, for I see now that that one is not meant for me.”

And so Olga went gracefully to the estates of Lieutenant Gratch, and wrote prettily worded letters home to her sisters, in which her verbs built castles and her datives sprung up like well-tended roses.

The second husband came when Marya was nine, and her sister Tatiana was sly and ruddy as a fox, her sharp grey eyes clapping upon every fascinating thing. Marya Morevna sat at her window embroidering the hem of a christening dress for Olga’s second son. It was spring, and the morning rain had left their long, thin street slick and sparkling, jeweled with wet pink petals. Marya watched from the upper floor as once more the birds gathered in the great oak tree, sniping and snapping for the soaked and wrinkled cherry blossoms, which every winged creature knows are the most savory of all blossoms, like spice cakes melting on the tongue. She laughed to see the plovers scuffle over the flowers, and as she did, the flock turned as one to look at her, their eyes like knifepoints. One of them, a little brown fellow, leaned perilously forward on his green branch and, without taking his gaze from Marya’s window, fell hard—thump, bash!—onto the streetside. But the little bird bounced up, and when he righted himself, he was a handsome young man in a handsome brown uniform with a long white sash, his buttons flashing like sunshine, his mouth round and kind.

The young man knocked at the great cherrywood door, and Marya Morevna’s mother smiled under his gaze.

“I am Lieutenant Zuyok of the White Guard,” he said, for the face of the world had changed. “I have come for the girl in the window. I have many wonderful houses full of fruits, many wonderful fields full of worms, and I have more jewels than she could wear, even if she changed her rings at morning, evening, and midnight each day of her life.”

“You must mean Tatiana,” said Marya’s mother, pressing her hand to her breast. “She is the second oldest and second most beautiful of my daughters.”

And so Tatiana, who had indeed sat at the first-floor window, which faced the garden full of apple blossoms and not the street, came to the door. She was filled like a silk balloon with the flaming sight of her handsome young man in his handsome brown uniform, and kissed him, not very chastely at all, on the mouth. They walked together through Gorokhovaya Street, and he bought for her a white hat with long chestnut-colored feathers tucked into its brim.

When they returned in the evening, Lieutenant Zuyok looked up into the turquoise sky and sighed. “This is not the girl in the window. But I will love her as though she was, for I see now that one is not meant for me.”

And so Tatiana went happily to the estates of Lieutenant Zuyok, and wrote sophisticated letters home to her sisters, in which her verbs danced in square patterns and her datives were laid out like tables set for feasting.

The third husband came when Marya was twelve, and her sister Anna was slim and gentle as a fawn, her blush quicker than shadows passing. Marya Morevna sat at her window embroidering the collar of a party dress for Tatiana’s first daughter. It was winter, and the snow on Gorokhovaya Street piled high and mounded, like long frozen barrows. Marya watched from the upper floor as once again the birds gathered in the great oak tree, sniping and snapping for the last autumn nuts, stolen from squirrels and hidden in bark-cracks, which every winged creature knows are the most bitter of all nuts, like old sorrows sitting heavy on the tongue. She laughed to see the shrikes scuffle over the acorns, and as she did, the flock turned as one to look at her, their eyes like bayonet points. One of them, a stately grey fellow with a red stripe at his cheek, leaned perilously forward on his green branch and, without taking his gaze from Marya’s window, fell hard—thump, bash!—onto the streetside. But the little bird bounced up, and when he righted himself, he was a handsome young man in a handsome grey uniform with a long red sash, his buttons flashing like streetlamps, his eyes narrow with a wicked cleverness.

The young man knocked at the great cherrywood door, and Marya Morevna’s mother frowned under his gaze.

“I am Lieutenant Zhulan of the Red Army,” he said, for the face of the world had begun to struggle with itself, unable to decide on its features. “I have come for the girl in the window. I have many wonderful houses which I share equally among my fellows, many wonderful rivers full of fish which are shared equally among all those with nets, and I have more virtuous books than she could read, even if she read a different one at morning, evening, and midnight each day of her life.”

“You must mean Anna,” said Marya’s mother, her hand firmly at her hip. “She is the third oldest and third most beautiful of my daughters.”

And so Anna, who had indeed sat at the first-floor window, which faced the garden full of bare branches and not the street, was brought to the door. She was filled like a pail of water with the sweet sight of her handsome young man in his handsome grey uniform, and with a terrible shyness allowed him to kiss only her hand. They walked together through the newly named Kommissarskaya Street, and he bought for her a plain grey cap with a red star on the brim.

When they returned in the evening, Lieutenant Zhulan looked up into the black sky and sighed. “This is not the girl in the window. But I will love her as though she was, for I see now that that one is not meant for me.”

And so Anna went dutifully to the estates of Lieutenant Zhulan, and wrote properly worded letters home to her sisters, in which her verbs were distributed fairly among the nouns, and her datives asked for no more than they required.

2

The Red Scarf

In that city by the sea which was now firmly called Petrograd and did not even remember, under pain of punishment, having been called St. Petersburg, in that long, thin house on that long, thin street, Marya Morevna sat by her window, knitting a little coat for Anna’s first son. She was fifteen years, fifteen days, and fifteen hours of age, the fourth oldest and fourth prettiest. She waited calmly for the birds to gather in the summer tr

ees, waited for them to do battle over thick crimson cherries, and for one of them to lean perilously forward on his branch, so very far forward—but no bird came, and she began to worry for herself.

She let her long black hair hang unbraided. She walked barefoot over the floorboards of the house on Gorokhovaya Street to preserve her only shoes for the long walk to school—and Marya, like a child whose widowed mother has married again, could never remember to call the long, thin street by its new name, having known it as Gorokhovaya for all her youth. There were other families in the house now, of course, for no fine roof such as this should be kept to one selfish patronym.

It was obscene to do so, Marya’s father agreed.

It is surely better this way, Marya’s mother said, nodding.

Twelve mothers and twelve fathers were stacked into the long, thin house, each with four children, drawing the old cobalt-and-silver curtains down the center of rooms to make labyrinths of twelve dining rooms, twelve sitting rooms, twelve bedrooms. It could be said, and was, that Marya Morevna had twelve mothers and twelve fathers, and so did all the children of that long, thin house. But all of Marya’s mothers laughed at her aimless manner. All her fathers looked troubled at her wild, loose hair. All their children stole her biscuits from the communal table. They did not like her, and she did not like them. They were in her house, in her things, and though it was surely virtuous to share, her stomach had not marched in any demonstration, and did not understand its patriotic duty. And if they thought her aimless, if they thought her a bit mad, let them. It meant they left her alone. Marya was not aimless, anyway. She was thinking.