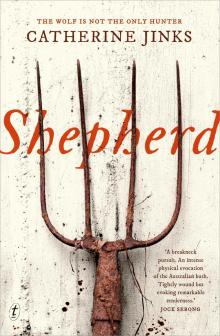

Shepherd

Catherine Jinks

ABOUT THE BOOK

Fourteen-year-old convict Tom Clay lives in a shepherd’s hut in the bush, protecting his master’s sheep from wild dogs. When a vicious fellow shepherd returns to ensure there are no witnesses to his crimes, the bush-crafty Tom and his hapless mate Rowdy face a life-and-death battle to survive.

Contents

Cover Page

About the Book

Title Page

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Epilogue

About the Author

Copyright Page

Prologue

I’M GOING to die.

My guts have turned to water. There’s no end to the purge; it’s like the cholera, though not as swift. I’ve seen folk die of the cholera. They turn blue and their eyes bug out.

There’s no one here to close my eyes. I’ll die like a dog and the dogs will eat my corpse.

Those berries have done for me.

It makes no sense because the blacks eat those berries. Whenever I’ve come upon a vine laden with the little orange balls, they’re never lower than a man can reach. A bird wouldn’t eat ’em from the ground up, nor an opossum neither. A kangaroo wouldn’t leave human footprints in the dirt beneath the vine.

I’d a notion that the blacks had bellies like an Englishman’s, but I must have been mistook. I should have listened to the warnings. Rowdy told me once that a friend of his, after seeing the blacks with palm pineapples, sampled a few of the seeds and died.

‘Those folk aren’t like us,’ Rowdy said. ‘They’re iron-gutted, like dogs.’ Perhaps he was right.

At home I always knew what to eat when. Dewberries in July. Sloes in September, though they were very tart unless you waited till after the first frost to pick ’em. Haws, hips, beechnuts, sorrel…there was so much to eat in the forests and the hedgerows.

When I first came here, I thought it a cruel affliction to walk through a wood and not know what bird was singing, or which plants were safe to eat. Now I understand it’s more than an affliction; it’s certain death.

I see nothing around me that I can properly name. Ferns. Vines. Bushes. Trees that shed their bark instead of their leaves. Flowers with spikes instead of petals.

I’m going to die wordless, in a lonely hollow in a strange land. I’m going to die among beasts that I don’t understand and plants that have killed me.

If I close my eyes and let my mind drift, I can pretend I’m asleep in the watch-box, with the dogs nearby. If the dogs were here, they would protect me. I can almost smell ’em; almost feel their warmth against my back.

But it’s dark. If they were here they’d be guarding the sheep, not me, because the sheep are more important than I am.

The sheep are the ones who plague my dreams, with their torn bellies and bloody haunches.

My duty is to the flock, always. Without it I’m nothing.

New South Wales, 1840

1

WHEN GYP’S bark wakes me, I’m in the watch-box. She must be barking at a beast because she sounds angry. If she were barking at a man she’d sound frightened.

This windowless watch-box is little more than an oversized coffin on legs. Its roof leaks and its walls are full of chinks but none of the gaps are big enough for me to see through. As for the square hole that serves as a door, it faces away from the sheepfold, towards the hut. We placed the box thus, Joe and I, to keep out the wind, which rarely blows from the west here in autumn. There’s nothing shielding the door save a piece of weathered canvas.

Since I can’t see what ails the dogs, I’ll have to climb out. But at least the lantern’s still alight, its glow faintly visible through the canvas. I can’t have been asleep for long; no more than three hours, at a guess.

I grope about for the musket, which I always keep in the watch-box with me, uncocked. Muskets are safer than lanterns because lanterns can be knocked over. I’m small for thirteen, but it’s so cramped in here that even someone my size could easily kick a lamp while sleeping.

I can hear three dogs, now. Gyp’s yap is clean and sharp, Pedlar’s low and gruff. The third dog is snarling—until suddenly it yelps.

Pushing aside the canvas flap, I clamber out of the watch-box and its funk of sweat and mildew. My lamp hangs from one of the four handles that stick out like wagon-shafts from the ends of the box. Whenever Joe and I have to carry it from one place to another, he complains that he might as well be a chairman. He’s told me about the swells at home who used to be carried about in boxes on poles, when the roads in England were so bad that you couldn’t use a carriage on half of ’em. His father was a chairman, he says, before a runaway horse broke his skull.

When I lift the lantern, I have a good view of the sheepfold, which is made of wooden hurdles lashed together with ropes. The sheep inside the fold mill about, bleating anxiously. They know they’re in danger. They can hear it. Smell it. They might even see it, despite the darkness.

But they can’t feel it; not yet. If they could they’d be screaming.

‘Gerrout! Get!’ My voice, clogged with sleep, breaks on a high note. Over by the fence, Gyp and Pedlar have cornered a wild dog. Teeth snap. Eyes glint. A flurry of fur unleashes a howl of pain.

At least it’s not a man. I’m told the blacks keep dogs, but I doubt there are blacks nearby. If there were they would have speared me by now.

‘Get! Go on!’ I’m closing in when the wild dog breaks free. He’s not a pure-bred—his tail’s like a whip—and he’s fast. Too fast. Once I put down the lantern I have to raise my gun, cock the flintlock, aim, fire. All the dog has to do is run.

When I pull the trigger the explosion makes my ears ring and my teeth buzz. I have to step through a drifting cloud of smoke to pick up the lantern. I swing it this way. That way. This way again.

I must have missed the damn mongrel; there’s no sign of it.

‘Tom?’

Joe Humble’s awake and peering through the doorway of our hut, which has no windows and no cracks in its slab walls, either, because Joe has filled every one. His bad chest keeps him away from cold draughts; you can hear the muck in his lungs when he speaks, all rough and rumbling. He says he’s not consumptive, but he’s so skinny and bent, with such hollow cheeks and deep-set eyes, that he might as well be. His eyebrows are in good health, though, thick and dark and thriving, for all that his hair and beard are wispy grey.

‘What’s amiss?’ He’s carrying a lantern and has wrapped a sheepskin around his shoulders.

‘Dogs.’

‘You sure o’ that?’

I know what he’s trying to say. He’s worried Dan Carver’ll come creeping back one night and slaughter us both.

‘I saw one.’

‘Lose any stock?’

I shake my head.

‘Check the hurdles,’ says Joe. Then he goes back inside.

He wants his rest and I can’t blame him. The hut was built for three—two shepherds and a hutkeeper. But with Carver gone, Joe must tend the sheep as well as cook, clean, fetch water and move hurdles. That’s why I’ve been sleeping in the watch-box lately, guarding the flock at night. Not that Joe ever used the watch-box, of course; he liked to doze against a tree at night, then nap during the day.

A hutkeeper can take such risks. No shepherd can.

The dogs are calmer now. Gyp stands guard, sniffing the air, as Pedlar weaves about with his nose in the dirt. Time to reload. Out comes the cartridge; I bite the paper at one end and tear it off. A pinch of black powder into the primi

ng pan, then the rest ends up in the barrel beneath the musket ball, which I tamp down with a ramrod.

Gyp barks.

‘I know. He’s still out there.’

With the musket slung over my shoulder, I circle the fold, shaking each hurdle to make sure it stands fast. In the place where the wild dog was cornered some of the ropes are loose.

When I hunker down to look, there are dark splashes in the dirt.

‘Gyp!’ God ha’ mercy, is she bleeding? I can’t be sure until I’ve felt her coat, because she’s black and white like all Scotch collies. But when I touch her black patches, she doesn’t whine or flinch.

Pedlar, being a yellow mongrel, would show a bloodstain—and there isn’t a drop on him.

‘Did you get the bastard? Good girl.’ Now that I look, I can see a trail of blood disappearing into the darkness. The wild dog must have been wounded when it ran. But how bad is the wound and how long the trail?

I’ll find out tomorrow.

My dreams are never good. In my poaching dreams, I’m always caught. In my dreams about Ma, she’s always on her deathbed. My father always beats me and my trial always ends on a hangman’s rope. Sometimes I dream that the ship bringing me to New South Wales founders and sinks. Sometimes I dream that I’m being flogged.

I never have been flogged, but I’ve witnessed many a flogging. They stay with me. So do the faces of the dead: my night-dog Lope, a pet lamb called Puff, a cat, my mother.

I’ve seen men die in bed. On the gallows. At the end of a knife. I never sleep well, no matter where I lay my head, because I’ve never laid my head down in safety. My father used to come home drunk and wake me with blows. On the ship there were always thieves and mollies prowling about. Here, in this place, I’ve heard tales of what the blacks have done to shepherds at night.

The watch-box is small and draughty and rank. It’s cold in winter and stifling in summer, but no worse than any other resting place.

I don’t think I’ve slept easy since I was in my mother’s womb.

I’m boiling water when Joe gets up.

‘There’s a blood trail,’ I tell him. ‘I should look for that wild dog or it might come back.’

Joe grunts, as usual. I’ve spent months in his company and know as little about him now as I did when we first met. He’s a thief from Lambeth, doing seven years. His wife is dead. He likes cooking.

I thought once that Joe was quiet because of Carver. It wasn’t wise to speak in Carver’s presence. But Carver has been gone for three weeks and Joe still doesn’t talk.

Not that I mind. I don’t like Joe. We’re here to do a job of work and survive as best we can. For friendship I have Gyp and Pedlar.

‘I’ll need the gun,’ I say. ‘For the wild dog.’

Joe hunches his shoulders. ‘You’ll come back after and tend to things,’ he growls. ‘I’ll be over-busy, else.’

By ‘things’ he means the sheepfold, the woodpile, the washing and the cooking. I’ve no cause to argue so I dip my stale damper into my tea and chew, gazing at the hearth—which doesn’t draw well, though it’s lined with good stone. Not that sulky fires trouble me, any more than smoky huts do. I take no offence at dirt floors, wobbly stools or creaky beds made of canvas lashed to wooden frames. Some folk have no beds. No tea. No fires. I rarely had ’em myself, when I was young. A one-roomed hut is riches when it sleeps only two men. Tea is riches when there’s sugar to sweeten it.

Now that Carver is gone, I’m able to find joy in these things. I still don’t feel safe, though.

When the tea is drunk and the damper ate, I take the musket outside, where Gyp is waiting for me. Pedlar is trying to dig a hole under the wall. The hut is barred to both of ’em on Joe’s orders, so Pedlar will always start digging whenever he smells food. I’ve filled a lot of holes lately.

‘Pedlar! Gerrout.’

The mongrel slinks away with a sidelong glance that’s a provocation. He has an ungovernable streak. My sensible Gyp, too dignified to scrabble in the dirt for a mouthful of mutton, comes trotting after me when I click my tongue.

We head for the blood trail.

The hut stands in a clearing full of tree-stumps. Beyond this grassy stretch a fence of thick forest lies in every direction, rising towards the south. A cart track passes through the clearing at its western end. The blood trail leads towards the brook beyond the eastern tree-line.

Gyp soon overtakes me, weaving and sniffing and skirting two headboards rammed into the ground. Though I haven’t enough book-learning to read the names on ’em, I know which is which. The one on the left says ‘Sam Jenkins’. The one on the right says ‘Walter Hogg’. I never met either man but I know how they died. Carver told me. He enjoyed telling me.

The trail stops at the brook, which is stony and sluggish, its banks churned up by sheep. There’s a mess of tracks in the mud and I’m casting about for fresh ones when Gyp yelps at me from the far bank. She’s prowling around a gap in the undergrowth—the entrance to an animal pad, formed by the passage of roaming beasts. A spot of blood stains the ground nearby.

‘Good girl.’ Ah, but she’s my treasure. ‘Good girl.’

All along the narrow path, a line of dark red drops leads us through an overgrown gully, a thicket of thorns and a stand of gum trees until it reaches the base of a rocky slope. I halt, wondering whether to go up or around.

Gyp knows. She heads uphill, her plumy tail waving. As we climb, the blood spots become smaller. By the time I gain the top of the slope, they’re gone and Gyp is trotting in circles, whining softly. She’s lost the trail.

I peer into the clefts between giant boulders cast about like builder’s rubble, but there’s nothing. Nothing on the hard, dry ground. Nothing on the grass stalks. The bloodstain I find on one patch of stone is dusty and faded and left by something much taller than a dog.

I unsling the gun and scan the silent bush. The sky is grey. The air is still.

There are blacks about; I know it. On my way up the hill I saw holes in the ground that weren’t dug by native badgers. The blacks in this country eat orchid roots; sometimes they dig around the base of trees. Joe claims they’ll eat anything: grubs, shit, each other. He has nothing good to say about the blacks.

Gyp barks, high-pitched and urgent. She’s yards away, tucked behind an outcrop of boulders that’s crowned with scrub.

‘I’m coming.’ And quickly, too, with many a backward look. I don’t like it here. This is close to where it happened. At the foot of this very hill, on the eastern side, is the place where I last saw Carver.

Now he’s gone; perhaps he crawled away to die. I hope so. I pray so.

Planted at one end of a fallen tree, Gyp is barking at its great root-ball, her hackles raised. One hiss from me and she falls silent. The log is hollow. Blood spots and paw-prints lead straight into its black heart.

Gyp watches me, panting. I hunker down and see only darkness inside the log. But I know the wild dog is there. I can feel it.

Good.

The wind is blowing from the south, straight into the root ball. I have a tin of Lucifer matches in my pocket, and there’s no shortage of kindling hereabouts: sticks and twigs and strips of bark. I gather up a handful while Gyp guards the log. She looks surprised when I drop my bundle onto the dirt beside her. But her ears prick and her eyes brighten as I make a noise like a match being struck. She bounds away, wagging her tail.

I collect more wood. There’s no movement inside the log; the silence stretches out, taut as a bat’s wing. I’m about to toss another load of kindling onto the heap when Gyp returns—with a stick so big that she has to drag it along behind her.

She adds it to my pile, then sits back and waits.

‘Gyp! Come bye!’ The command sends her streaking to the other end of the log. A sharp ‘There!’ makes her freeze. Her eyes don’t move from the hole in front of her even when I scrape a match across sandpaper half a dozen times.

At last the head flares and I touch it to a spr

ig of dry grass. A wisp of smoke, a lick of flame and the fire is burning. I don’t stay to watch the smoke blow into the root ball but go and stand by Gyp, aiming my gun at the log’s rear exit.

Now we must wait. And wait. Smoke seeps through cracks in the wood. A lizard scuttles into the sunlight. Something cracks.

Suddenly—boom!—the wild dog erupts out of the root ball and dashes through the fire, scattering sparks. Gyp races after it. ‘Gyp! No!’ I can’t risk a shot or I might hit her…

Dammit.

In Ixworth I used to trap eels. I would drop a noose around the mouth of a muddy burrow then wait by the water, still as stone, until the eel thrust its head out. If I was quick and the noose was smooth I could have an eel on the bank with one pull. It took a deal of patience, a stretch of clear water and a good length of copper wire.

There’s no copper wire here. Even if there was, I’d be hard put to snare a wild dog in a noose. An eel can’t smell you but a dog can.

I don’t know who owns the eels in this country. The King, no doubt. He owns ’em all, back home, though my father wouldn’t have it so. My father used to argue that poaching wasn’t theft because wild animals were gifts from God. No matter how much common land a gentleman might have enclosed, there wasn’t a single partridge in all of England that truly belonged to him, so my father said.

Some of the farmers near Ixworth had bills posted once, forbidding the collection of mushrooms and bilberries on their land. My father tore down every bill he could find and used them as spills to light candles. He hated being told what to do.

He wouldn’t have lasted long in New South Wales.

I can’t find that dog.

Perhaps he went to ground in a badger’s burrow. The brown badgers here dig burrows bigger than anything I’ve seen at home—burrows that would fit a nursing sow with ease. I’ve heard that the blacks send their youngsters down these burrows to hunt, though I’m not sure if it’s true.

I once saw the chamber inside a badger’s burrow and it was easily as big as a watch-box. The blacks had dug down to it, I’d guess, since the chamber had its own chimney. I’m sure a roast badger is well worth sinking a six-foot shaft for, even with tools made of shell and stone. Not that the blacks are ill-equipped. They can carve a weapon so finely balanced that it returns to you when you throw it.