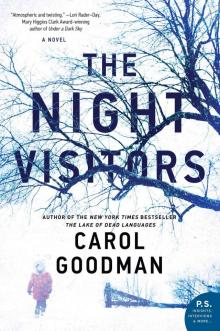

The Night Visitors

Carol Goodman

Dedication

To the people of Family,

the true kindly ones

Epigraph

A name can change one’s core identity:

“The Furies” thus became “The Kindly Ones,”

Athena ending senseless cruelty.

A name can change one’s core identity.

Benevolence diverts from treachery;

and, shining like her crown, pure goodness wins.

A name can change one’s core identity:

“The Furies” thus became “The Kindly Ones.”

—Lee Slonimsky

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One: Alice

Chapter Two: Mattie

Chapter Three: Alice

Chapter Four: Mattie

Chapter Five: Alice

Chapter Six: Mattie

Chapter Seven: Alice

Chapter Eight: Mattie

Chapter Nine: Alice

Chapter Ten: Mattie

Chapter Eleven: Alice

Chapter Twelve: Mattie

Chapter Thirteen: Alice

Chapter Fourteen: Mattie

Chapter Fifteen: Alice

Chapter Sixteen: Mattie

Chapter Seventeen: Alice

Chapter Eighteen: Mattie

Chapter Nineteen: Alice

Chapter Twenty: Mattie

Chapter Twenty-One: Alice

Chapter Twenty-Two: Mattie

Chapter Twenty-Three: Alice

Chapter Twenty-Four: Mattie

Chapter Twenty-Five: Alice

Chapter Twenty-Six: Mattie

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Alice

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Mattie

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Alice

Chapter Thirty: Mattie

Chapter Thirty-One: Alice

Chapter Thirty-Two: Mattie

Chapter Thirty-Three: Alice

Chapter Thirty-Four: Mattie

Chapter Thirty-Five: Alice

Acknowledgments

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .*

About the Author

About the Book

Read On

Praise

Also by Carol Goodman

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Alice

OREN FALLS ASLEEP at last on the third bus. He’s been fighting it since Newburgh, eyelids heavy as wet laundry, pried up again and again by sheer stubbornness. Finally, I think when he nods off. If I have to answer one more of his questions I might lose it.

Where are we going? he asked on the first bus.

Someplace safe, I answered.

He stared at me, even in the darkened bus his eyes shining with too much smart for his age, and then looked away as if embarrassed for me. An hour later he’d asked, as if there hadn’t been miles of highway in between, Where’s it safe?

There are places, I’d begun as if telling him a bedtime story, but then I’d had to rack my brain for what came next. All I could picture were candy houses and chicken-legged huts that hid witches. Those weren’t the stories he liked best anyway. He preferred the book of myths from the library (it’s still in his pack, racking up fines with every mile) about heroes who wrestle lions and behead snake-haired monsters.

There are places . . . I began again, trying to remember something from the book. Remember when Orestes flees the Furies and he goes to some temple so the Furies can’t hurt him there?

It was the temple of Apollo at Delphi, Oren said, and it’s called a sanctuary.

No one likes a smarty-pants, I countered. Since he found that mythology book he likes to show off how well he’s learned all those Greek names. He’d liked Orestes right away because their names were alike. I’d tried to read around the parts that weren’t really for kids, but he always knew if I skipped over something and later I saw him reading the story to himself, staring at the picture of the Furies with their snake hair and bat wings.

At the next bus stop he found the flyer for the hotline. It was called Sanctuary, as if Oren’s saying the word had made it appear. I gave him a handful of change to buy a candy bar while I made the call. I didn’t want him to hear the story I’d have to tell. But even with him across the waiting room, standing at the snacks counter, his shoulders hunched under the weight of his Star Wars backpack, he looked like he was listening.

The woman who answered the phone started to ask about my feelings, but I cut to the chase and told her that I’d left my husband and taken my son with me. He hit me, I said, and he told me he’d kill me if I tried to leave. I have no place to go . . .

My voice had stuttered to a choked end. Across the waiting room, Oren had turned to look at me as if he’d heard me. But that was impossible; he was too far away.

The woman’s voice on the phone was telling me about a shelter in Kingston. Oren was walking across the waiting room. When he reached me he said, It can’t be a place anyone knows about.

I rolled my eyes at him. Like I didn’t know that. But I repeated his words into the phone anyway, trying to sound firm. The woman on the other end didn’t say anything for a moment, and looking into Oren’s eyes, I was suddenly more afraid than I’d been since we left.

I understand, the woman said at last, slowly, as if she were speaking to someone who might not understand. I recognized the social worker’s “explaining” voice and felt a prickle of anger that surprised me. I’d thought that I was past caring what a bunch of morally sanctimonious social workers thought about me. We can arrange for a safe house, one no one will know about. But you might have to stay tonight in the shelter.

Oren shook his head as if he could hear what the woman said. Or as if he already knew I’d messed up.

It has to be tonight, I said.

Again the woman paused. In the background a cat meowed and a kettle whistled. I pictured a comfortable warm room—framed pictures on the walls, throw pillows on a couch, lamplight—and was suddenly swamped by so much anger I grew dizzy. Oren reached out a hand to steady me. The woman said something but I missed it. There was a roaring in my ears.

. . . give me the number there, she was saying. I’ll make a call and call you right back.

I read her the number on the pay phone and then hung up. Oren handed me a cup of hot coffee and a doughnut. How had he gotten all that for a handful of change? Does he have money of his own he hasn’t told me about? I slumped against the wall to wait, and Oren leaned next to me. It will be all right, I told him. These places . . . they have a system.

He nodded, jaw clenched. I touched his cheek and he flinched. I looked around to see if anyone had noticed, but the only other occupants of the station were a texting college student, the old woman behind the snacks counter, and a drunk passed out on a bench. When the phone rang I nearly jumped out of my skin.

I picked up the phone before it rang again. For a second all I heard was breathing and I had the horrible, crazy thought that it was him. But then the woman spoke in a breathless rush, as if she’d run somewhere fast. Can you get the next bus for Kingston?

I told you no shel— I began, but the woman cut me off.

At Kingston you’ll get a bus to Delphi. Someone will meet you there, someone you can trust. Her name’s Mattie—she’s in her fifties, has short silvery hair, and she’ll probably be wearing something purple. She’ll take you to a safe house, a place no one knows about but us.

I looked down at Oren and he nodded.

Okay, I said. We’ll be there on the next bus.

I hung up and knelt down to tell Oren where we were going, but he was already handing something to me: two tickets for the

next bus for Kingston and two for Delphi, New York. Look, he said, the town’s got the same name as the place in the book.

That was two hours and two buses ago. The last bus has taken us through steadily falling snow into mountains that loom on either side of the road. Oren had watched the swirling snow as if it were speaking to him. As if he were the one leading us here.

It’s just a coincidence, I tell myself, about the name. Lots of these little upstate towns have names like that: Athens, Utica, Troy. Names that make you think of palm trees and marble, not crappy little crossroads with one 7-Eleven and a tattoo parlor.

I was relieved when Oren fell asleep. Not just because I was tired of his questions, but because I was afraid of what I might ask him—

How did you know where we were going? And how the hell did you get those tickets?

—and what I might do to get the answer out of him.

Chapter Two

Mattie

I WAKE UP to the sound of a train whistle blowing. Such a lonesome sound, my mother used to say. I’ve never thought so. To me it always sounded like the siren call of faraway places. I used to lie in bed imagining where those tracks led. Out of these mountains, along the river, down to the city. Someday I’d answer that call and leave this place.

It takes me a moment to realize that it’s my phone ringing that has woken me. And then another few moments to realize that I’m not that girl plotting her escape. I’m a woman on the wrong side of fifty, back where she started, with no way out but one.

The phone’s plugged in on my nightstand. One of my young college interns showed me how to set it so only certain people can get through.

But what if someone who needs me has lost their phone and is calling from a phone booth? I asked.

She blinked at me like I was a relic of the last century and asked, Do they even have those anymore?

You ought to get out more, Doreen always tells me. Come down to the city with me.

It must be Doreen on the phone. She’s the only one on the list of “favorites,” aside from Sanctuary’s number, that I’d programmed into the phone. When the college girl saw that puny list she hadn’t been able to hide the pity in her eyes.

I reach for the phone, past pill bottles, paperbacks, and teacups—all my strategies to coax sleep—and manage to knock it over for my pains. I hear Dulcie stir, the vibration of the impact waking her. “It’s okay, girl,” I croon even though she can’t hear me. “It’s just Doreen riled up about something.”

I swing my legs around onto the floor, the floorboards cold on my bare feet, and lean down to find the phone. The screen is lit up with Doreen’s face (the college intern showed me how to do that too, taking a picture from Doreen’s Facebook page of her protesting at the Women’s March in January). Her mouth is open, midshout, which is kind of a joke because Doreen almost never shouts. She has the calmest voice of anyone I know. She could talk anyone down, the volunteers say. That’s why she always takes the hotline for the midnight to six A.M. shift, those hours when the worst things happen. Men stumble home drunk from bars and women lock their guns away. Teenagers overdose and girls find themselves out on the road without a safe ride home—or take the wrong one. Which one of those terrible things has happened to make Doreen call me in the middle of the night?

I draw my finger across the screen to answer. “Hi, Doreen.”

“Oh thank God, Mattie,” she says in a breathless rush as if she’d been running. Doreen always sounds like that. She ran away from her abusive ex seventeen years ago, after he slammed her son’s head up against the dining room wall, and sometimes I think she’s still running. “I thought you’d let your phone die again.”

“No, I just knocked it over. What is it? A bad call?”

Sometimes Doreen will call me because she’s upset by a call. I don’t mind. No one should have to sit alone in the night with the things we have to hear.

“A domestic violence case. Left home,” she says, and my heart sinks. I let out a sigh and feel a pressure against my leg. Dulcie has picked up on my distress and come over to lean against me.

“With a child?” I ask, hoping the answer is no.

“A ten-year-old boy. She was in the Newburgh bus station. I offered the Kingston shelter but she said no. She said it had to be a place no one could find her.”

“Oh,” I say, reaching down to stroke Dulcie’s soft head.

“I checked availability at St. Alban’s and Sister Martine said they could take her,” Doreen says, “but someone needs to pick her up at the bus station and take her there.”

The sisters at St. Alban’s are one of our best links on the domestic violence underground railroad. Their convent is on the river, gated, and guarded by a Mother Superior who would face down a dozen angry husbands come searching for their wayward women. It’s a chilly place to wash up after you’ve left your home in the night, though: the nuns in their long black habits, the bare cells, the crucifixes on the walls. I think of that ten-year-old boy, of what he’ll feel like in that cold gray place—

“I could call Frank,” she says. I hear the hesitation in her voice. Has the woman told her something that makes Doreen think that it might not be a good idea to call our local chief of police—or has she just sensed that there might be some reason to keep the law out of it for now? Or maybe she’s just uneasy saying Frank’s name to me. Doreen has a theory that Frank Barnes has a crush on me. I’ve tried to tell her how wrong she is about that, but Doreen doesn’t buy it.

“I’ll pick them up and take them,” I say, already getting up and reaching for the light switch. The weight against my leg slides away as the light floods the room. Doreen is saying something to me, something about the woman that had troubled her or something that the woman had reminded her of, but I don’t catch it. I’m staring at the dog bed at the foot of the bed. I’d moved it there a couple of weeks ago because I kept tripping over Dulcie on my way to the bathroom. She’s lying there now. Fast asleep.

THERE’S NO TIME to dwell on the phantom pressure on my leg. Diabetic nerve pain? Menopausal hot flash? The early-onset Alzheimer’s that felled my mother by my age? More important, the woman and the boy will be arriving at the bus station in an hour. It’s only a fifteen-minute drive from the house, but that’s assuming the car starts and there’s no ice to scrape off the windows and the roads are plowed. While I’m pulling on leggings and jeans, thermal top and sweater, I go to the window to look out. The view of my backyard is a gray-and-white blur of ominous lumps and dark encroaching forest. I can’t tell if the snow in the yard is fresh or if the gray in the air is fog or falling snow. There’s no back porch light to catch the falling flakes. You should fix that, I hear my mother’s voice saying. You’re letting the place go to seed.

You should mind your own business, I tell her right back. She’s been dead for thirty-four years. When will her voice get out of my head?

Dulcie is up and shambling by my side by the time we reach the top of the stairs. One of these days we’re going to topple ass-over-teakettle together down the steep slippery wooden steps and one of us will wind up in rehab. I’m not laying any bets on who’ll survive the fall.

Downstairs, Dulcie heads straight for the back door to be let out as if it’s morning. I don’t like letting her out in the dark; the snow is deep out there and there are coyotes in the woods, but I don’t have time to walk her, so unless I want to come home to a puddle, I’d better.

“Stay close,” I tell her, as if she could still hear me, or would listen if she could. I step out with her and feel the sting of icy rain on my face. Crap. That won’t make for easy driving.

I turn on the kettle and get out two thermoses from the drying rack. There’s nothing but tea in my pantry and that won’t do for mother or son. There’s a box of donations in the trunk of my car, though, that I think had some hot chocolate in it. I should get the car started anyway.

I go out the front door and nearly slide right off the porch. I’ll have to salt that.

Avoiding the broken third step on the way down is tricky (one of these days that will be the end of you, I hear my mother helpfully point out) and the ground below is white with newly fallen snow. There’s a good six inches on the car, all of it covered with a glaze of ice. The scraper’s in the trunk, which is also sealed by ice. I use my fist to break through the ice over the front door and dig through six inches of powder to find another coating of ice over the door handle. As if the weather gods had decided to layer their efforts to thwart me.

It’s not always about you, Mattea, says my mother’s reproving voice.

I go back inside, grab the kettle, and bring it back out to deice the car. It takes three trips to get the door open and another two for the trunk. When I turn the key in the ignition I hear the exasperated mutter of the fifteen-year-old engine. “I know,” I say, looking up at the religious medal hanging from the rearview mirror, “but there’s a boy and his mother waiting for us at a bus station.”

Whether from divine intervention or because the engine’s finally warm enough, the car starts. I turn the rear and front defrosters on high and thank Anita Esteban, the migrant farmworker who gave me the Virgin of Guadalupe medal fourteen years ago. When I told Anita that I didn’t believe in God she’d pressed the medal into my hand and told me that I should just say a prayer to whatever I did believe in. So I say my prayers to Anita Esteban, who left her drunk, no-good husband, raised three children on her own, went back to school, and earned a law degree. She’s what I believe in.

I get the box of donations out of the trunk and bring it back to the kitchen, where I find enough hot cocoa to make up a thermos. I’ll buy coffee at the Stewart’s. There are Snickers bars in the box too, which I put in my pack. Of course the sisters will feed them, but their larder tends to the bland and healthy. That boy will need something sweet.

I’m closing up the box when I spot a bag of dog treats. I take out two Milk-Bones and turn toward Dulcie’s bed . . . and see the open door. I feel my heart stutter: all this time I spent fussing with the car she’s been outside in the cold. I open the screen door to find her standing withers deep in the snow, head down, steam shrouding her old grizzled head.